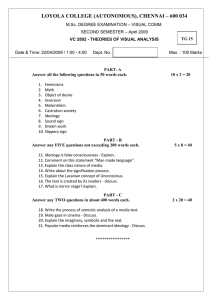

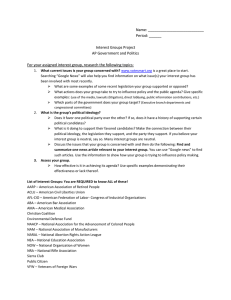

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283792888 Work-Family Role Conflict and Well-Being Among Women and Men Article in Journal of Career Assessment · November 2015 DOI: 10.1177/1069072715616067 CITATIONS READS 6 154 3 authors, including: Liat Kulik Bar Ilan University 105 PUBLICATIONS 954 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Liat Kulik on 04 May 2016. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Article Work–Family Role Conflict and Well-Being Among Women and Men Journal of Career Assessment 1-18 ª The Author(s) 2015 Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1069072715616067 jca.sagepub.com Liat Kulik1, Sagit Shilo-Levin1, and Gabriel Liberman2 Abstract The main goal of the present study was to examine gender differences in the variables that explain the experience of role conflict and well-being among Jewish working mothers versus working fathers in Israel (n ¼ 611). The unique contribution of the study lies in its integrative approach to examining the experience of two types of role conflict: work interferes with family (WIF) and family interferes with work (FIW). The explanatory variables included sense of overload, perceived social support, and gender role ideology. The findings revealed that for women, both FIW and WIF conflict correlated negatively with well-being, whereas for men, a negative correlation with well-being was found only in the case of FIW conflict. Contrary to expectations, social support contributed more to mitigating negative affect among men than among women. On the whole, the findings highlight the changes that men have experienced in the work–family system. Keywords FIW conflict, WIF conflict, social support, gender role ideology, overload The main goal of the present study was to examine gender differences in the variables that explain the experience of role conflict and well-being among Jewish working fathers and mothers in the Israel. Greenhaus and Beutell (1985) argued that work–family conflict ‘‘arises from simultaneous pressures from the work and family domains that are mutually incompatible’’ (p. 77). In light of the expansion of women’s role set following the addition of paid employment outside of the home, most of the studies dealing with the impact of multiple roles on well-being have been conducted among women (e.g., see recent studies by Kapur, 2014; Kulik & Liberman, 2013). However, changes in gender roles in recent years have also affected men’s role set, as reflected in the terms ‘‘new men’’ (Messner, 1993) and ‘‘new fathers’’ (Johansson, 2011). Especially in the young generation, men have become more involved in household tasks and childcare than they were in the past (IshiiKuntz, 2013). Thus, as fathers today may also experience role strain due to the conflicting demands 1 2 Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel Data-Graph Research & Statistical Consulting, Holon, Israel Corresponding Author: Liat Kulik, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel. Email: kulikl@mail.biu.ac.il Downloaded from jca.sagepub.com at Bar-Ilan university on May 4, 2016 2 Journal of Career Assessment Gender Role Ideology -+ -+ FIW Conflict Overload + + WIF Conflict Social Support + + WB: positive affect WB: negative affect - Figure 1. The hypothesized model. of work and family, the impact of multiple roles on men’s well-being has become a popular topic among researchers in the fields of family and career studies (Brown & Sumner, 2013; Jones, Burke, & Westman, 2013). Notably, comparative studies on men’s and women’s experiences of role conflict have focused specifically on examining the gender differences in the level of conflict generated by the interference of work with family responsibilities (WIF) and the interference of family responsibilities with work (FIW; e.g., Fu & Shaffer, 2001). Other studies have included gender as one factor in models that aim to explain the determinants and consequences of role conflict among working parents (e.g., Kulik, Shilo-Levin, & Liberman, 2014). Yet in most cases, researchers have not examined the gender differences in the set of variables that explain the experience of role conflict or the distinctive impact of role conflict on well-being among men versus women. Based on existing knowledge in the fields of work and family on the one hand and gender on the other, the research model aimed to explain the experience of role conflict and its outcomes (the experience of well-being) for men versus women. Thus, the model was examined separately for each gender. The explanatory variables included in the research model were overload, gender role ideology, and perceived social support. In light of the existing empirical knowledge, we expected some of the paths in the models to be similar for both genders, whereas others were expected to be unique for each gender (see Figure 1—the Hypothesized Research Model). Role Conflict and Emotional Well-Being: Gender Differences The role conflict perspective is based on two premises. According to the first premise, because individuals have limited time and energy, the demands of performing simultaneous multiple roles (work and family roles) lead to the experience of role conflict (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985). According to the second premise, the experience of role conflict causes psychological distress and exhaustion and reduces the sense of well-being (Baltes & Heydens-Gahir, 2003). As for gender differences, which were the main focus of the present study, researchers have found differences in the levels of WIF and FIW conflict experienced by men and women. For example, findings have revealed that women experience higher levels of FIW conflict (Fu & Shaffer, Downloaded from jca.sagepub.com at Bar-Ilan university on May 4, 2016 Kulik et al. 3 2001), whereas men experience higher levels of WIF conflict (Gutek, Searle, & Klepa, 1991). However, as mentioned, there is not enough empirical evidence to enable prediction of gender differences in the set of variables that explain the experience of WIF and FIW conflict or differences in the relationships between both types of role conflict and emotional well-being. Based on the conceptualization of emotional well-being as a two-dimensional construct (Mroczek & Kolarz, 1998), in the present study, we examined the contribution of the experience of role conflict (WIF and FIW) and other related variables to explaining positive affect as well as negative affect among working fathers versus working mothers. Despite the changes in gender roles in recent decades, research findings indicate that as they did in the past, women still devote significantly more hours than men to household chores and childcare (e.g., Goñi-Legaz, Ollo-López, & Bayo-Moriones, 2010), whereas men devote significantly more hours to the work domain than women (e.g., Stier, 2010). Thus, as in the past, women still show a greater tendency than men to perceive family roles as their main responsibility, whereas men show a greater tendency to perceive the employment role as their main responsibility (Christiansen & Palkovitz, 2001). Although the experience of both types of role conflict (WIF and FIW) may harm the emotional being of men and women (Adams, Bornat, & Prickett, 1996; Kulik & Liberman, 2013), it can be assumed that women are more sensitive to the interference of work demands with the family domain, whereas men are more sensitive to the interference of family demands with the work domain. Hence, we expected to find gender differences in the relationship between role conflict and well-being, as reflected in the following hypotheses: Hypothesis 1: The higher the level of WIF conflict, the lower the level of positive affect and the higher the level of the negative affect will be among both genders. This relationship will be stronger for women than for men. Hypothesis 2: The higher the level of FIW conflict, the lower the level of positive affect and the higher the level of the negative effect will be among both genders. This relationship will be stronger for men than for women. Correlates of Role Conflict and Well-Being Researchers have focused on individual as well as on environmental factors that are determinants of the experience of well-being (for a meta-analysis, see Michel, Kotrba, Mitchelson, Clark, & Baltes, 2011). Following this approach, we integrated two factors in our research model that have been mentioned in the literature as major correlates of role conflict (FIW and WIF): the sense of overload (a factor that intensifies role conflict) and perceived social support (a factor that inhibits role conflict). Moreover, following the approach of Korabik, McElwain, and Chappell (2008), who suggested that not only sociodemographic aspects of gender but also the intrapsychic aspects of gender should be considered in explaining the behavior of men and women, we included the participants’ gender role ideology in the research model. This variable has been neglected so far in research on role conflict, with the exception of only a few studies (e.g., Drach-Zahavy & Somech, 2004; Rajadhyaksha & Velgach, 2009). Sense of overload can stem from the multiple demands of the work and family domains and is considered by researchers in the field to be a major factor that explains role conflict and its harmful consequences (e.g., Michel et al., 2011). The terms role conflict and sense of overload tend to be used interchangeably in the literature, when in fact they refer to distinct concepts. Role conflict refers to the extent to which a person experiences pressures within one role that are incompatible with the pressures arising within another role (Kopelman, Greenhaus, & Connolly, 1983). In contrast, role overload, which is often one of the determinants of role conflict, is experienced only when Downloaded from jca.sagepub.com at Bar-Ilan university on May 4, 2016 4 Journal of Career Assessment the demands of one role make it difficult to fulfill the demands of other roles (Coverman, 1989). Based on this conceptualization, the following hypothesis was put forth: Hypothesis 3: For both men and women, the greater their sense of overload, the higher their sense of role conflict (WIF and FIW) will be. Social support was conceptualized as the perceived flow of informational, emotional, instrumental, and appraisal support from different sources (House, Umberson, & Landis, 1988). Researchers have emphasized the importance of perceived social support as a construct that is related to reducing the experience of stress in many life domains, including role conflict (for a meta-analytic review, see Michel et al., 2011). It has been argued that social support plays two distinct roles with regard to stress deriving from the work–family interface (for a review, see Michel et al., 2011). First, it may directly reduce the experience of role conflict; second, it may buffer or moderate the relationships between the experience of role conflict and the indicators of well-being. The literature indicates that at times of stress, women show a greater tendency to seek and receive emotional support than men do (Belle, 1987; Flaherty & Richman, 1989). Moreover, although there are mixed findings regarding gender differences in the experience of emotion, studies have indicated that women generally express emotion with greater intensity than men do (for a meta-analysis, see Else-Quest & Grabe, 2012). Therefore, even though both men and women can experience role conflict to the same extent, because women tend to express more emotions than men, they can define the kind of support they need in order to alleviate their distress more clearly than men (Arnocky, Sunderanib, Alberta, & Norrisa, 2014). Thus, the type of support they receive might be more consistent with their expectations and with their specific needs than the type of support that men receive. As a result, social support may contribute to reducing the experience of role conflict to a greater extent among women than among men. Against this background we hypothesized: Hypothesis 4: The greater the extent of perceived social support, the lower the levels of both types of role conflict (WIF and FIW) will be. This relationship will be stronger for women than for men. In light of the above argument that women may benefit more from social support than men, it can also be expected that social support might alleviate the negative effects of stress (as expressed here in the two types of role conflict) on well-being to a greater extent for women than for men. Hypothesis 5: Perceived social support will moderate the relationship between the experience of role conflict (WIF and FIW) and well-being (positive and negative affect). The moderating effect will be stronger for women than for men. Gender role ideology generally refers to opinions and beliefs about the division of family and work roles according to gender (Harris & Firestone, 1998). It is commonly believed that gender role ideology is shaped in a process of socialization or learned through experience (Lachman, 1991). These attitudes typically run along a continuum from traditional to egalitarian. Traditional gender role attitudes reinforce or conform to expected differences in feminine and masculine roles, whereas egalitarian gender role attitudes do not support the segregation of roles by gender and maintain that family and work roles should be shared equally by men and women. The few empirical studies that have examined the relationship between the gender role ideology and the experience of WIF and FIW conflict have yielded mixed results. Some of them have revealed a relationship between the gender role ideology and the experience of role conflict (Ayman, Veigach, & Ishaya, 2005), whereas others have not (Drach-Zahavy & Somech, 2004). Downloaded from jca.sagepub.com at Bar-Ilan university on May 4, 2016 Kulik et al. 5 We included gender role ideology in our research model as an antecedent of role conflict and derived our hypothesis regarding its impact from gender role theory (Pleck, 1995). Based on this theory, it can be assumed that the relationship between gender role ideology and the experience of role conflict will be different for men and women. Accordingly, men with a traditional gender role ideology, who perceive the role of worker to be most important, will be more sensitive to the interference of family demands with the work domain (FIW conflict) than will men with an egalitarian gender role ideology, who are more tolerant of this interference. Based on the same rationale, it can be assumed that women with a traditional gender role ideology, who consider their family role to be most important, will be more sensitive to the interference of work demands with the family domain (WIF conflict) than women with a more egalitarian gender role ideology. In keeping with this perspective, Somech and Drach-Zahavy (2007) have shown that gender role ideology affects people’s choice of strategies for resolving work–home conflict. That is, people with a traditional gender role ideology tend to use conflict resolution strategies that conform to traditional gender role expectations. Against this background, the following hypothesis was put forth: Hypothesis 6: The more traditional the men’s gender role ideology, the greater the intensity of FIW conflict and lower the intensity of WIF conflict will be. Hypothesis 7: The more traditional the women’s gender role ideology, the greater the intensity of WIF conflict and the lower the intensity of FIW conflict will be. Contributions of the Study The unique contribution of the present study lies in its integrative approach to examining the experience of the two types of role conflict (WIF and FIW) among men versus women. Moreover, in the hypothesized model, we integrated the construct of gender role ideology as one of the main factors that may explain the experience of role conflict. Method Sample There were 611 participants in the study (300 men and 311 women). All of them performed at least two main roles: they were parents and they worked for pay outside of the home in various occupations covering a broad range of professional categories (the criteria guiding the selection of organizations for drawing the sample of participants are described in the Procedure section). The average number of children was 2.82 (SD ¼ 1.21), and participants ranged in age from 22 to 66 years (M ¼ 44.93, SD ¼ 13.27). With regard to education, 5% of the participants had partial secondary education, 33.1% had completed a secondary diploma, and 61.9% had postsecondary education (academic or other). As for religiosity, 38% of the participants defined themselves as secular, 24% defined themselves as traditional, 36% defined themselves as religious, and 2% defined themselves as ultra-Orthodox. No significant gender differences in the above-mentioned background variables were revealed in t-tests or in w2 tests. However, differences were found between men and women with regard to hours of paid work per week: t(609) ¼ 6.26, p < .001. That is, the men worked more hours per week for pay than did the women (M ¼ 41.27, SD ¼ 14.80 and M ¼ 34.29, SD ¼ 14.80, respectively). In addition, gender differences were found with regard to employment in management positions: (including low management positions) 57% of the men worked in management positions versus 33.1% of the women: w2(1) ¼ 35.21, p < .001. Downloaded from jca.sagepub.com at Bar-Ilan university on May 4, 2016 6 Journal of Career Assessment Instruments Role conflict. The original questionnaire was developed by Frone and Rice (1987) and examined the intensity of role conflict generated by the demands of family and the workplace. The questionnaire included 18 items which were divided into two factors: 9 items relating to role conflict caused by interference of family with work demands (FIW; e.g., ‘‘Because of pressure at home, I am often concerned with family matters at work’’) and 9 items relating to role conflict caused by interference of work with family demands (WIF; e.g., ‘‘Because of my work, I do not participate in as many family activities as I would like to’’). The scale of responses ranged from 1 (not true at all) to 5 (very true). For each factor, one score was derived by calculating the mean of the items in the factor: the higher the score, the greater the intensity of each type of role conflict. Using this questionnaire, Kulik and Liberman (2013) found that WIF conflict and FIW conflict correlated positively with distress in the family and at work among working mothers. The Cronbach’s a reliability of the items representing FIW conflict in the present study was .85, and the reliability of the items representing WIF conflict was .85. General overload questionnaire. The questionnaire included 3 items, which were adapted from measures developed by Chou and Robert (2008) and Vanfossen (1981). The 3 items in the questionnaire were (1) ‘‘There is usually not enough time to do high-quality work,’’ (2) ‘‘I have too many things to do at once,’’ and (3) ‘‘People expect too much of me.’’ The scale of responses ranged from 1 (not true at all) to 5 (very true). The questions were found to be related to low satisfaction with work (Chou & Robert, 2008) and to high levels of depression (Vanfossen, 1981). The content of the questionnaire used in the present study was validated by two judges who specialize in research on stress and who agreed that the three questions are valid measures of overload among working people. The Cronbach’s a reliability of the items in the present study was .72. One score was derived by computing the mean of the items in the scale: the higher the score, the more intense the experience of overload. Gender role ideology questionnaire. The questionnaire was developed in Hebrew by Kulik (2013) and included 35 statements that describe gender roles in the home, at work, and in society (e.g., ‘‘Fathers should not be as involved as mothers in raising children’’). Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they agree with each statement on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The higher the score, the more egalitarian the participants’ gender role ideology. Kulik (2013) found a significant association between men’s egalitarian gender role ideology and the time they devote to the household. The Cronbach’s a internal consistency of the items in the questionnaire was .84. Social support questionnaire. The original scale for perceived social support was developed by Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, and Farley (1988) and contained 24 items. In the present study, we used a shortened version of the scale developed by Blumenthal et al. (1987), which consisted of 12 items that examine perceived emotional support (e.g., ‘‘I have a close person with whom I can share sorrow and joy’’). Responses were based on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (doesn’t reflect my feelings at all) to 7 (reflects my feelings to a great extent). One score was derived by computing the mean of the items in the scale. A high score indicated that the level of perceived social support among the participants was high. The extent of perceived social support assessed by this questionnaire was found to be related to higher challenge at the time of appraisals of work stress among social workers and nurses (Ben-Zur & Michael, 2007). The Cronbach’s a reliability of the questionnaire used in this study was .88. Downloaded from jca.sagepub.com at Bar-Ilan university on May 4, 2016 Kulik et al. 7 Well-being questionnaire. The construct was measured by Watson, Clark, and Tellegen’s (1988) Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, which contains two subscales. One scale measures positive affect (e.g., happy, lively, and active), and the other measures negative affect (e.g., sad, afraid, and downhearted). Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they experienced each of these feelings over the past month on a scale ranging from 1 (very little or not at all) to 5 (extremely). Two scores were derived: a mean score for positive affect—the higher the score, the more the participant experienced positive feelings over the past month and a mean score for negative affect—the higher the score, the more the participant experienced negative feelings over the past month. Gallagher and Meurs (2015) found that positive affect evaluated through this questionnaire helps cope with stress and overload. As for negative affect, a substantial body of evidence has indicated that general negative affect is a core feature of many types of psychopathology (e.g., Stanton & Watson, 2014). The Cronbach’s a reliabilities of the scale used in the present study were .87 for positive affect and .85 for negative affect. Background questionnaire. The questionnaire provided data on the following variables: age, marital status, profession, religiosity (secular, traditional, religious, or ultra-Orthodox), number of children, number of children living at home, and children’s ages. Procedure Research questionnaires were distributed at workplaces throughout the country. The criterion that guided the selection of organizations for sampling of participants in the study was the representation of various categories of organizations in Israel: industrial organizations, service organizations, and commercial organizations. Based on this criterion, questionnaires were distributed in a diverse range of organizations: high-tech companies, government ministries, educational institutions, industrial plants, and business organizations. After making arrangements with the directors of the organizations, questionnaires were distributed to workers who met the criteria for participation in the study, that is, parents who were employed in full-time or part-time jobs and who had children living at home. All of the participants responded to the questionnaires voluntarily. In each organization, workers were sampled randomly and approached to participate in the study. Some of the participants filled out the questionnaires at the time they were distributed and returned them to the research assistants on the same day. Others filled out the questionnaires at home and returned them later to the research assistants. The time required to fill out the questionnaire was about 25 min. After the research assistants approached the people who agreed to participate in the study several times, a high response rate was attained (80%). Methods of Measurement and Estimation Before examining the research hypotheses, several preliminary calculations were carried out. First of all, measures of descriptive statistics were calculated for the seven research variables (gender role ideology, overload, social support, the two dimensions of role conflict—FIW and WIF, and the two dimensions of emotional well-being—positive and negative affect). Correlations between the main research variables were calculated (Table 1). All of the measures of skewness and kurtosis were below 1.00, except for the measure of social support. It can therefore be assumed that the distribution of variables was normal. Afterward, we created measures for each of the latent variables through item parceling, a common method in structural equation modeling (SEM) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), which facilitates normalization of the variables (Wang & Wang, 2012). First, we conducted separate factor analyses for each of the research variables. In so doing, the analyses were limited to creating one Downloaded from jca.sagepub.com at Bar-Ilan university on May 4, 2016 8 Journal of Career Assessment Table 1. Means, Standard Deviations, and Zero-Order Correlations Between the Research Variables. 1 1. Age 2. Economic situation 3. Education 4. Overload 5. Gender role ideology 6. Social support 7. FIW conflict 8. WIF conflict 9. Well-being: positive affect 10. Well-being: negative affect M SD 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 — .19** — .12** .22** — .02 .06 .15** — .02 .14** .21** .24** — .17** .03 .20** .16** .21** — .15** .15** .05 .31** .32** .09* — .07 .06 .01 .31** .28** .09* .62** — .03 .13** .06 .07 .26** .34** .18** .19** .05 .08* .07 44.93 13.29 3.32 0.73 3.73 0.73 .30** .27** .16** 2.77 0.70 3.75 0.64 4.06 0.73 .39** 2.28 0.74 9 — .30** .24** 2.55 0.82 10 3.42 0.62 — 1.88 0.62 Note. N ¼ 611. *p < .05, **p < .01. factor. Following these analyses, the items were arranged in order of their loadings on the factor and parcels were formed, which included items with high, moderate, and low loadings. Finally, the measures were established by calculating the means for each group of items. Data analysis was conducted in two stages. In the first stage, we designed a confirmatory model that aimed to formulate operative indices representing the research variables. In the second stage, a structural model was designed to test the hypotheses. The model aimed to examine the relationships between the exogenous variables (background variables, overload, gender role ideology, social support, and the two types of role conflict—FIW and WIF) and the two endogenous variables (the two dimensions of well-being—negative affect and positive affect). The confirmatory model and the structural model were examined on the basis of SEM using the Mplus program (Muthen & Muthen, 2007). To fill in the missing data, which constituted less than 1% of the data obtained from the sample, we used the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) method with an MLR algorithm. The MLR estimator in Mplus stands for Maximum Likelihood with Robust Standard Errors. This method is considered to be less biased than other methods such as imputation (Enders & Bandalos, 2001). Results CFA We examined the loadings of the measures on the latent variables (overload, gender role ideology, the two role conflict dimensions, and the two dimensions of well-being) separately for men and women. Pearson’s Correlations Between the Latent Research Variables Table 2 presents the Pearson’s correlations between the latent variables for men and women, respectively (correlations for men are above the diagonal, and correlations for women are below the diagonal). To examine whether there are significant gender differences in the correlations patterns, we conducted Fisher Z tests. With few exceptions, the findings in Table 2 show similar patterns of correlations between the research variables for men and women. Downloaded from jca.sagepub.com at Bar-Ilan university on May 4, 2016 Kulik et al. 9 Table 2. Correlations Between the Latent Variables: Men and Women.a 1. Overload 2. Gender role ideology 3. Social support 4. FIW conflict 5. WIF conflict 6. Well-being: positive affect 7. Well-being: negative affect 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 — .16* .16* .33** .41** .14* .29** .39** — .24** .27** .26** .27** .27** .26** .21** — .13 .15* .45** .16* .43** .42** .07 — .76** .19** .45** .46** .36** .08 .69** — .28** .38** .04 .35** .31** .24** .14* — .29** .51** .39** .26** .41** .39** .29** — a Men above the diagonal, women below the diagonal. *p < .05, **p < .01. Overload. The findings indicate that perceived overload correlated positively with the two types of role conflict (FIW and WIF) for men and women, and the Fisher Z tests revealed no significant gender differences in the strength of the correlations. Perceived overload also correlated positively with negative affect for men and women: The greater their sense of overload, the more they experienced negative affect. The Fisher Z tests revealed that the correlations between sense of overload and negative affect were significantly higher for men than for women: Z ¼ 3.23, p < .001. A low significant negative correlation was found between sense of overload and positive affect among women but not among men. Gender role ideology. The findings indicate that the more liberal the gender role ideology of the men and women, the lower the intensity of role conflict was (FIW and WIF). However, the Fisher Z tests revealed that the correlations between a liberal gender role ideology and an FIW conflict were significantly higher for men than for women: Z ¼ 83.0, p < .001. For men and women, gender role ideology correlated with positive and negative affect: The more liberal their gender role ideology, the better their well-being (i.e., more positive affect and less negative affect). In addition, the more liberal their gender role ideology, the higher their level of perceived social support and the lower their sense of overload. Notably, Fisher Z tests revealed gender differences in the correlation patterns between gender role ideology and sense of overload: Z ¼ 3.20, p < .001. That is, the correlation was higher for men than for women. Perceived social support. For both men and women, negative correlations were found between perceived social support and overload: The higher their levels of perceived social support, the lower their sense of overload. Fisher Z tests revealed that the strength of the correlation between these variables was similar for men and women. For men, perceived social support did not correlate significantly with both types of role conflict. For women, the findings revealed that the higher their levels of perceived social support, the lower their levels of WIF conflict were. However, perceived social support correlated positively with well-being for men as well as for women: The higher the level of perceived social support, the less they experienced negative affect and the more they experienced positive affect. Role conflict. The two types of role conflict (FIW and WIF) correlated with the negative and positive dimensions of well-being for men as well as for women: The greater the intensity of both types of role conflict, the less they experienced positive affect and the more they experienced negative affect. Fisher Z tests revealed no gender differences in the strength of the correlations. Downloaded from jca.sagepub.com at Bar-Ilan university on May 4, 2016 10 Journal of Career Assessment Gender Differences in the Main Research Variables t-Tests for independent samples, which aimed to examine gender differences in the research variables, revealed that the women had a more egalitarian gender ideology than the men: M ¼ 3.85, SD ¼ .63 and M ¼ 3.66, SD ¼ .80, respectively, t(609) ¼ 3.76, p < .01. Moreover, the experience of WIF conflict was lower for women than for men: M ¼ 2.42, SD ¼ .80 and M ¼ 2.60, SD ¼ .82, respectively, t(609) ¼ 4.17, p < .01. In addition, the women experienced more negative affect than the men: M ¼ 1.96, SD ¼ .64 and M ¼ 1.79, SD ¼ .57, respectively, t(609) ¼ 3.54, p < .01. No gender differences were found in the rest of the research variables. The Structural Equation Model The direct and indirect relationships between the independent research variables (overload, gender role ideology, and social support) and the outcome variables (FIW and WIF conflicts and the two dimensions of well-being) were examined separately for men and women through the structural equation model. The goodness-of-fit coefficients for the confirmatory research model reveal a good model data fit for men as well as for women: Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) ¼ .944, comparative fit index (CFI) ¼ .957, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) ¼ .045, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) ¼ .047, degree of freedom (df) ¼ 224, w2 ¼ 361.745, p < .001 for men and TLI ¼ .943, CFI ¼ .956, RMSEA ¼ .045, SRMR ¼ .046, df ¼ 224, w2 ¼ 368.165, p < .001 for women. For the men, the research variables (background variables, overload, the two role conflict factors, social support, and gender role ideology) explained 23% of the variance in positive affect (R2 ¼ .23, p < .001) and 36% of the variance in negative affect (R2 ¼ .36, p < .001). For the women, the research variables explained 28% of the variance (R2 ¼ .28, p < .001) and 26% of the variance (R2 ¼ .26, p < .001) in positive and negative affect, respectively. The following is a comparative description of the path coefficients among men versus women, in the order they appeared in the research model (see Figure 2 and Figure 3). Overload. Comparison of the path coefficients between the explanatory research variables, the two types of role conflict (FIW–WIF) and the two dimensions of well-being, revealed some differences and some similarities between men and women. For men, overload correlated positively with FIW and WIF conflicts and with well-being (positive and negative affect). Moreover, higher levels of overload were found among participants who received low levels of social support as well as among those with a traditional gender role ideology. Overload was found to mediate the relationship between gender role ideology and FIW conflict (b ¼ .098, SE ¼ .037, p < .01) as well as the relationship between gender role ideology and WIF conflict (b ¼ .131, SE ¼ .042, p < .01). That is, the more egalitarian the man’s gender role ideology, the lower his sense of overload; and the lower his sense of overload, the lower the intensity of both types of role conflict were. Similarly, overload mediated the relationship between gender role ideology and negative affect (b ¼ .114, SE ¼ .043, p < .01): The more egalitarian the men’s gender role ideology, the lower the intensity of overload was and the less they experienced negative affect. For women, overload was positively associated with both dimensions of role conflict (FIW and WIF). Thus, in general, the findings partially confirmed Hypothesis 3 for men as well as for women. Moreover, an indirect negative relationship was found between overload and the intensity of positive affect, which was mediated by WIF conflict (b ¼ .090, SE ¼ .045, p < .05). That is, the higher the women’s sense of overload, the more they experienced WIF conflict; and the higher their level of WIF, the lower their levels of positive affect were. In addition, an indirect positive relationship was found between overload and the intensity of negative affect, which was mediated by FIW conflict (b ¼ .110, SE ¼ .030, p < .01). Downloaded from jca.sagepub.com at Bar-Ilan university on May 4, 2016 Kulik et al. 11 Figure 2. The structural model for men. That is, the higher the women’s sense of overload, the more they experienced FIW conflict; and the more they experienced FIW conflict, the higher their levels of negative affect were. Role conflict. The structural equation model for men revealed a path between FIW conflict and the two dimensions of well-being: The more the men experienced FIW conflict, they higher their levels of negative affect and the lower their levels of positive affect were. However, WIF conflict did not correlate significantly with any of the dimensions of well-being among men. The women’s structural equation model shows that FIW conflict correlated positively with negative affect, whereas WIF conflict correlated negatively with positive affect (partially confirming Hypotheses 1 and 2). Gender role ideology. For both men and women, the findings revealed that egalitarian gender role ideology was related to lower levels of both types of role conflict and to higher levels of wellbeing, as reflected in high-positive affect and low-negative affect (partially confirming Hypotheses 6 and 7). However, a negative correlation between gender role ideology and sense of overload was only found for men: The more egalitarian the men’s gender role ideology, the lower their sense of overload was. Perceived social support. No significant correlation was found between perceived social support and the experience of role conflict (FIW and WIF) among men or women (failing to confirm Hypothesis 4). However for men, a relationship was found between perceived social support and the two dimensions of well-being: The higher the level of perceived social support among men, the more they experienced positive affect and the less they experienced negative affect. In the women’s model, a positive relationship between perceived social support and well-being was only found for positive Downloaded from jca.sagepub.com at Bar-Ilan university on May 4, 2016 12 Journal of Career Assessment Figure 3. The structural model for women. affect: The higher the level of perceived social support among women, the more they experienced positive affect. Here, we hypothesized that perceived social support will moderate the relationship between the experience of role conflict and well-being. In order to examine the interactions, both types of role conflict were entered as dependent variables, perceived social support was entered as a moderating variable, and the two dimensions of well-being were entered as dependent variables. The following interactions were found for men: perceived social support moderated the relationship between both types of role conflict, FIW (b ¼ .23, SE ¼ .05, p < .001) and WIF (b ¼ .17, SE ¼ .04, p < .001), and the intensity of negative affect: When the men reported high levels of perceived social support, the intensity of both types of role conflict was not related to negative affect. However, when their levels of perceived social support were low, the relationships between role conflict and negative affect were significant (partially confirming Hypothesis 5 for men). A similar pattern was also found for women with regard to the relationship between role conflict and negative affect: FIW (b ¼ .13, SE ¼ .06, p < .05). That is, when the women’s levels of perceived social support were high, the intensity of role conflict was not related to the experience of negative affect; however, when the levels of perceived social support were low, the intensity of role conflict was significantly associated with the experience of negative affect (partially confirming Hypothesis 5 for women). Gender Differences in SEM Path Coefficients In addition to examining differences in the paths of the relationships between the research variables among men versus women, we conducted SEM multigroup analysis to examine whether there were gender differences in the construct regression weights (SEM path coefficients; Wang & Wang, Downloaded from jca.sagepub.com at Bar-Ilan university on May 4, 2016 Kulik et al. 13 Table 3. Comparison of Path Coefficients for Overload, Gender Role Ideology, and Social Support With Role Conflict (FIW and WIF): Men Versus Women. FIW Conflict Men Women WIF Conflict Wald Men Women Wald Overload .30*** (.08) .32*** (.07) .20, p ¼ .66 .40*** (.08) .38*** (.08) .05, p ¼ .83 Gender role ideology .33*** (.07) .19** (.07) 1.24, p ¼ .27 .25*** (.07) .19** (.07) .45, p ¼ .50 Social support .02 (.06) .06 (.07) .81, p ¼ .37 .02 (.06) .07 (.07) .89, p ¼ .35 *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .01. Table 4. Path Coefficients for Social Support, Overload, and Gender Role Ideology With Positive and Negative Affect: Men Versus Women. Positive Affect Men WIF conflict FIW conflict Social support Overload Gender role ideology .01 .19* .28*** .23* .30*** (.10) (.10) (.07) (.10) (.07) Women .24* (.11) .10 (.10) .40*** (.07) .003 (.09) .14* (.07) Negative Affect Wald 3.19, 4.20, 1.99, 2.57, 1.92, p p p p p ¼ .07 ¼ .04 ¼ .16 ¼ .11 ¼ .17 Men .03 .17* .13* .35*** .18* (.09) (.08) (.06) (.10) (.07) Women .02 (.11) .34** (.10) .05 (.06) .14 (.08) .13* (.06) Wald 0.00, p 1.99, p 0.60, p 1.88, p 0.02, p ¼ ¼ ¼ ¼ ¼ .99 .16 .44 .17 .88 *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. 2012). Tables 3 and 4 present the multigroup results for the structural equation model that was used to compare the path coefficients in the models for men and women. Each of the tables presents the path coefficients for the different sets of variables included in the models as well as the Wald values, which represent the extent of similarity between the path coefficients for men and women. A large Wald value indicates that there is a difference between the same paths across the two subsets, whereas a small value indicates that there are no differences. Even though the comparison of SEM paths in the structural models for men and women revealed several gender differences in the paths of the associations of the research variables with role conflict and the dimensions of well-being, only a few of the differences in the path coefficients were significant. One of the significant differences was in the relationship between FIW conflict and wellbeing: The correlation between FIW conflict and positive affect was only significant for men but not for women. WIF conflict was not associated with either of the dimensions of well-being for men, but a negative association was found between WIF conflict and positive affect for women. Nonetheless, the significance of gender differences in the strength of the path coefficients was borderline. Another difference between men and women in the path coefficients was found in the association between the two types of role conflict: For men, the strength of the association between FIW and WIF conflict was significantly lower than it was for women: Wald F2 with F3 ¼ 3.72, p ¼ .05. Discussion In contrast to previous studies, which focused on examining gender differences in the intensity of role conflict (FIW and WIF), the main contribution of the present study was the examination of gender differences in the set of variables that explain role conflict as well as gender differences in the relationship between role conflict and well-being among working fathers and mothers. On the whole, besides the similarities that were revealed between men and women, there were also certain Downloaded from jca.sagepub.com at Bar-Ilan university on May 4, 2016 14 Journal of Career Assessment differences in the paths of the explanatory variables and the outcome variables in the confirmatory models for men and women. This finding indicates that in some aspects, the experience of role conflict is distinct for each gender. Regarding gender differences in the intensity of role conflict, the findings revealed that men experience more WIF conflict than women. However, no gender differences were found with regard to FIW conflict. The finding that men and women experience similar levels of FIW conflict contradicts the results of earlier studies in the field, which have revealed that the levels of FIW conflict are higher for women (e.g., Fu & Shaffer, 2001). Our finding may be indicative of changes in the approach of the new man to the work–family system (Hearn et al., 2012). Today, new men have adopted fatherhood as a major part of their identity, and family responsibilities are an important part of their agenda (Pleck, 2010). Thus, they may experience more interference of work with their family life than men did in the past, and their levels of FIW conflict may be similar to the levels experienced by their wives. Another explanation for the similarities between men and women in the experience of FIW conflict relates to rapid developments in telecommunications today (e.g., the extensive use of cellular phones, text messages, and ‘‘WhatsApp’’), which give children easy access to both of their parents at almost any time and place. This development can intensify the interference of family with the work domain, so that the experience of this conflict is similar for men and women. Consistent with these explanations, some research findings have revealed that men experience even more FIW conflict today than women (e.g., Eagle, Miles, & Icenogle, 1997). However, besides the similarities in the experience of FIW conflict, men still experience more WIF conflict than women do, apparently because they often have more senior jobs than women (Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, 2015), as reflected in the occupational characteristics of the present study sample. Notably, the findings revealed that the correlation between the experience of FIW conflict and WIF conflict was significantly stronger for women than for men. Thus, it can be argued that men are better able to separate the experiences of the two types of conflict, whereas women are more likely to experience a spillover effect (Demerouti, 2012) from one type of conflict to the other. Regarding the specific research hypotheses, the women’s experience of WIF conflict correlated with positive affect (but not with negative affect), whereas the men’s experience of WIF conflict did not correlate with either dimension of well-being. A possible explanation for this finding relates to the men’s and women’s perceptions of their main roles. Because men still perceive themselves as the main providers and give more priority to work than women do (Kulik, 2013), they may expect to experience interference of work with family responsibilities. Hence, when this happens, it does not detract from their well-being. As for women, because they are usually responsible for the household domain and devote many more hours per week to household chores than men do (Stier, 2010), the interference of work with family responsibilities may have a stronger impact on them and cause greater harm to their well-being. As for the relationship between FIW conflict and well-being, in light of the above-mentioned gender differences in responsibilities for the work and family domains, the relationship between FIW conflict and positive affect was found only among men, and there was no significant relationship between WIF and negative affect for both genders. For both men and women, as expected, the sense of overload as well as traditional gender role ideology correlated positively with both types of role conflict (FIW and WIF). Moreover, the paths of the correlations between the explanatory research variables indicate that a high sense of overload characterizes men with low levels of social support who maintain a traditional gender role ideology. Thus, it is possible that men with traditional attitudes regarding gender roles manifest their nonegalitarian perspectives in their daily lives by focusing on the traditional role of primary breadwinner, as expressed in numerous hours of paid work per week. As a result, they experience high levels of overload. Egalitarian gender role ideology also correlated with high levels of perceived social support and well-being (i.e., higher positive affect and lower negative affect) for both men and women. Downloaded from jca.sagepub.com at Bar-Ilan university on May 4, 2016 Kulik et al. 15 The benefits of egalitarian perspectives have also been revealed in another study, which found that people with egalitarian gender role attitudes tend to be more flexible and have higher self-esteem (e.g., Kulik, 2004). Despite the similarities between men and women in the contribution of egalitarian gender role ideology to their emotional well-being, in some ways, it appears that men benefit more than women from adopting egalitarian perspectives: Egalitarian gender role ideology was related to a lower sense of overload for men, and the experience of less overload contributed to higher levels of well-being. Thus, it is possible that men with an egalitarian gender role ideology show a greater tendency to be involved in maintaining the household, which creates a pleasant atmosphere in the home and consequently enhances marital quality (Kulik, 2013). This, in turn, contributes to the experience of higher emotional well-being among men (high-positive affect and low-negative affect). Regarding social support, no significant correlation was found with the experience of role conflict (FIW and WIF) among men or women. A possible explanation for this unexpected finding relates to the type of support assessed in the present study versus the main type of support required to alleviate role conflict. Whereas the participants’ assessments of social support in the present study focused on perceived emotional support, it is also important to receive instrumental support such as assistance with household chores or assistance with performing tasks in the workplace in order to alleviate the experience of FIW and WIF. Moreover, although the moderating role of perceived social support for women was evident only in the relationship between FIW conflict and negative affect, perceived social support moderated the relationship between both types of role conflict (FIW and WIF) and the intensity of negative affect for men. As for the other results of the present study, the explanation for these findings can also be attributed to the characteristics of the new man. In this connection, it has been argued that the new man no longer avoids expressing feelings of distress (Messner, 1993), so that he can mobilize the social support he needs and alleviate negative affect. In sum, the research findings shed new light on the masculine image in terms of the experience of FIW conflict. In contrast to the prevailing assumption that FIW role conflict is predominant among women, the findings of this study indicate that today, this type of role conflict is experienced equally by men and women, whereas WIF conflict is predominant among men. Furthermore, contrary to expectations, levels of perceived social support were found to be similar for men and women, and men benefited from it even more than women did. Before concluding, several limitations of the study need to be taken into account. First, the study was conducted in Israel, which is a familistic society in the midst of rapid modernization (Lavee & Katz, 2003). Hence, the participants’ experience of role conflict might have been influenced by the familistic nature of Israeli society. Another limitation relates to the cross-sectional design of the study, in which data on the explanatory variables and outcome variables were collected at the same point in time. As such, there is no way of conclusively determining the causal relationships between the outcome variables and the explanatory variables. In order to gain deeper insights into the issue of gender differences in the experience of role conflict, there is a need to expand the scope of the research on this issue to less familistic societies and use a longitudinal design. Moreover, in future research, it would be worthwhile to examine whether the model used in this study to examine the gender differences in the relationship between role conflict and well-being applies to other stages of the life cycle, such as young couples without children or couples who are still working in late adulthood and whose children have left home. As for practical recommendations, the relatively high levels of WIF found among the men participating in this study indicate that new men need guidance in alleviating this type of conflict. Moreover, the findings highlight the contribution of egalitarian gender role ideology to alleviating the experience of role conflict and improving the emotional well-being of both men and women. Therefore, it would be worthwhile for practitioners in the field to instill egalitarian attitudes among the young generation and to highlight its contributions among working individuals. Downloaded from jca.sagepub.com at Bar-Ilan university on May 4, 2016 16 Journal of Career Assessment Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. References Adams, J., Bornat, J., & Prickett, M. (1996). Care planning and life-history work with frail older women. London, England: Jessica Kingsley. Arnocky, S., Sunderanib, S., Alberta, G., & Norrisa, K. (2014). Sex differences and individual differences in human facilitative and preventive courtship. Interpersona, 8, 210–221. doi:10.5964/ijpr.v8i2.159 Ayman, R., Velgach, S., & Ishaya, N. (2005). Multi-method approach to investigate work-family conflict. Poster presented at the meeting of the Society for Industrial Organizational Psychology, Los Angeles, CA. Baltes, B. B., & Heydens-Gahir, H. A. (2003). Reduction of work-family conflict through the use of selection, optimization, and compensation behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 1005–1018. doi:10.1037/ 0021-9010.88.6.1005 Belle, D. (1987). Gender differences in the social moderators of stress. In R. C. Barnett, L. Biener, & G. K. Baruch (Eds.), Gender and stress (pp. 257–277). New York, NY: Free Press. Ben-Zur, H., & Michael, K. (2007). Burnout, social support, and coping at work among social workers, psychologists, and nurses: The role of challenge/control appraisals. Social Work in Health Care, 45, 63–82. doi:10.1300/J010v45n04_04 Blumenthal, J. A., Burg, M. M., Barefoot, J., Williams, R. B., Haney, T., & Zimet, G. D. (1987). Social support, type A behavior and coronary artery disease. Psychosomatic Medicine, 49, 331–340. doi:10.1097/ 00006842-198707000-00002 Brown, T. J., & Sumner, K. E. (2013). The work-family interface among school psychologists and related school personnel: A test of role conflict and expansionist theories. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43, 1771–1776. doi:10.1111/jasp.12121 Chou, R. J. A., & Robert, S. A. (2008). Workplace support, role overload, and job satisfaction of direct care workers in assisted living. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 49, 208–222. doi:10.1177/ 002214650804900207 Christiansen, S., & Palkovitz, R. (2001). Why the ‘‘good provider’’ role still matters: Providing as a form of paternal involvement. Journal of Family Issues, 22, 84–106. doi:10.1177/019251301022001004 Coverman, S. (1989). Role overload, role conflict, and stress: Addressing consequences of multiple role demands. Social Forces, 67, 965–982. doi:10.1093/sf/67.4.965 Demerouti, E. (2012). The spillover and crossover of resources among partners: The role of work-self and family-self facilitation. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 17, 184–198. doi:10.1037/a0026877 Drach-Zahavy, A., & Somech, A. (2004). Emic and etic characteristics of coping with WFC: The case of Israel. Paper presented at the International Congress of Cross-Cultural Psychology, Xi’an, The People’s Republic of China. Eagle, B. W., Miles, E. W., & Icenogle, M. L. (1997). Interrole conflicts and the permeability of work and family domains: Are there gender differences? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 50, 168–184. doi:10.1006/jvbe. 1996.1569 Else-Quest, N. M., & Grabe, S. (2012). The political is personal: Measurement and application of nation-level indicators of gender equity in psychological research. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 36, 131–144. doi:10. 1177/0361684312441592 Downloaded from jca.sagepub.com at Bar-Ilan university on May 4, 2016 Kulik et al. 17 Enders, C. K., & Bandalos, D. L. (2001). The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling, 8, 430–457. doi:10.1207/s15328007SEM0803_5 Flaherty, J., & Richman, J. (1989). Gender differences in the perception and utilization of social support: Theoretical perspectives and an empirical test. Social Science & Medicine, 28, 1221–1228. doi:10.1016/ 0277-9536(89)90340-7 Frone, M., & Rice, R. W. (1987). Work-family conflict: The effect of job and family involvement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13, 723–729. doi:10.1108/EUM0000000005936 Fu, C. K., & Shaffer, M. A. (2001). The tug of work and family: Direct and indirect domain-specific determinants of work-family conflict. Personnel Review, 30, 502–522. doi:10.1108/EUM0000000005936 Gallagher, V. C., & Meurs, J. A. (2015). Positive affectivity under work overload: Evidence of differential outcomes. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l’Administration, 32, 4–14. doi:10.1002/cjas.1309 Goñi-Legaz, S., Ollo-López, A., & Bayo-Moriones, A. (2010). The division of household labor in Spanish dual earner couples: Testing three theories. Sex Roles, 63, 515–529. doi:10.1007/s11199-010-9840-0 Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10, 76–88. doi:10.5465/AMR.1985.4277352 Gutek, B. A., Searle, S., & Klepa, L. (1991). Rational versus gender role explanations for work-family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 560–568. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.76.4.560 Harris, R. J., & Firestone, J. M. (1998). Changes in predictors of gender role ideologies among women: A multivariate analysis. Sex Roles, 38, 239–252. doi:10.1023/A:1018785100469 Hearn, J., Nordberg, M., Andersson, K., Balkmar, D., Gottzén, L., Klinth, R., & Sandberg, L. (2012). Hegemonic masculinity and beyond: 40 years of research in Sweden. Men and Masculinities, 15, 31–55. doi:10.1177/1097184X11432113 House, J. S., Umberson, D., & Landis, K. R. (1988). Structures and processes of social support. Annual Review of Sociology, 14, 293–318. doi:10.1146/annurev.so.14.080188.001453 Ishii-Kuntz, M. (2013). Work environment and Japanese fathers’ involvement in child care. Journal of Family Issues, 34, 250–269. doi:10.1177/0192513X12462363 Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. (2015). Leket netunim leregel yom haisha habenleumi [Selected statistics published on the occasion of International Women’s Day]. Media release, published on March 4, 2015 (Hebrew). Jerusalem, Israel: Author. Johansson, T. (2011). The construction of the new father: How middle-class men become present fathers. International Review of Modern Sociology, 37, 111–126. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/ 41421402 Jones, F., Burke, R. J., & Westman, M. (Eds.). (2013). Work-life balance: A psychological perspective. Abingdon, England: Psychology Press. Kapur, S. (2014). Work-family conflict among working women. Journal of Research, 51, 323–325. Kopelman, R. E., Greenhaus, J. H., & Connolly, T. F. (1983). A model of work, family, and interrole conflict: A construct validation study. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 32, 198–215. doi:10.1016/ 0030-5073(83)90147-2 Korabik, K., McElwain, A., & Chappell, D. B. (2008). Integrating gender-related issues into research on work and family. In K. Korabik, D. S. Lero, & D. L. Whitehead (Eds.), Handbook of work-family integration: Research, theory, and best practices (pp. 215–232). London, England: Academic Press. Kulik, L. (2004). Predicting gender-role attitudes among mothers and their adolescent daughters in Israel. Affilia, 19, 437–449. doi:10.1177/0886109904268930 Kulik, L. (2013). Bishulim, siddurim o tikunim? Mabatam shel gevarim al hishtatfutam b’aavodot bayit [Cooking, errands, or repairs? Men’s perspective of household tasks]. Hevra urevaha [Society and Welfare], 33, 385–414 (Hebrew). Downloaded from jca.sagepub.com at Bar-Ilan university on May 4, 2016 18 Journal of Career Assessment Kulik, L., & Liberman, G. (2013). Work-family conflict, resources and role set density: Assessing their effects on distress among working mothers. Journal of Career Development, 40, 445–465. doi:10.1177/ 0894845312467500 Kulik, L., Shilo-Levin, S., & Liberman, G. (2014). Multiple roles, role satisfaction and sense of meaning in life: An extended examination of role enrichment theory. Journal of Career Assessment. doi:10.1177/ 1069072714523243 Lachman, M. E. (1991). Perceived control over memory aging: Developmental and intervention perspectives. Journal of Social Issues, 47, 159–175. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1991.tb01840.x Lavee, Y., & Katz, R. (2003). The family in Israel: Between tradition and modernity. Marriage & Family Review, 35, 193–217. doi:10.1300/J002v35n01_11 Messner, M. A. (1993). ‘‘Changing men’’ and feminist politics in the United States. Theory and Society, 22, 723–737. doi:10.1007/BF00993545 Michel, J. S., Kotrba, L. M., Mitchelson, J. K., Clark, M. A., & Baltes, B. B. (2011). Antecedents of workfamily conflict: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32, 689–725. doi:10.1002/ job.695 Mroczek, D. K., & Kolarz, C. M. (1998). The effect of age on positive and negative affect: A developmental perspective on happiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 1333–1349. doi:10.1037/00223514.75.5.1333 Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Mplus user’s guide (6th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Author. Pleck, J. H. (1995). The gender role strain paradigm: An update. In R. F. Levant & W. S. Pollack (Eds.), A new psychology of men (pp. 11–32). New York, NY: Basic Books. Pleck, J. H. (2010). Fatherhood and masculinity. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (pp. 27–57). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley. Rajadhyaksha, U., & Velgach, S. (2009). Gender, gender role ideology and work-family conflict in India. Paper presented at the Academy of Management Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL. Somech, A., & Drach-Zahavy, A. (2007). Strategies for coping with work-family conflict: The distinctive relationships of gender role ideology. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12, 1–19. doi:10.1037/10768998.12.1.1 Stanton, K., & Watson, D. (2014). Positive and negative affective dysfunction in psychopathology. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 8, 555–567. doi:10.1111/spc3.12132 Stier, H. (2010). Has the era of single-earner families ended? In V. Muhlbauer & L. Kulik (Eds.), Working families in Israel (pp. 17–46). Rishon LeZiyon, Israel: Hamichlala Leminhal College (Hebrew). Vanfossen, B. E. (1981). Sex differences in the mental health effects of spouse support and equity. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 22, 130–143. doi:10.2307/2136289 Wang, J., & Wang, X. (2012). Structural equation modeling: Applications using Mplus. West Sussex, England: Wiley. Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070. doi:10. 1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063 Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52, 30–41. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2 Downloaded from jca.sagepub.com at Bar-Ilan university on May 4, 2016 View publication stats