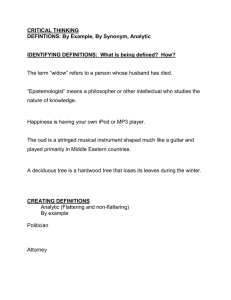

Chapter 13 QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS Immersion in the Data Just as you immerse yourself in the field when you are collecting data, in qualitative analysis it is essential to immerse yourself in the data. This happens in a number of ways. First, there is no substitute for doing your own transcription. When you transcribe interview data from tapes, you engage a number of senses and begin the immersion process. It is a good idea to keep your field journal nearby to make analytic notes as you transcribe. You will then read transcripts many times in order to become completely familiar with the data. How many times? There is no set number. However, a good guide is that if you come up with an analytic insight, you know exactly where to go in any data to find supporting or disconfirming evidence. Preliminary Informal Analysis Even as you are interviewing a participant or observing in the field, you are already thinking analytically. Fortunately, as thinking human beings, we can't help it. Again, be sure your field journal is handy, and write down everything that comes to your mind. Do not trust your memory. No idea or hunch is too insignificant to write down. Analytic Memos Analytic memos can be written anywhere: on a napkin, in your field journal, in a transcript, even recorded at the end of an interview when you are by yourself. Analytic memos are dated and include relevant information, as well as the memo itself. Memos can be short or long, but should contain enough information that you know what you were thinking when you made them. Finding Codes or Themes A code is a concept that is given a name that most exactly describes what is being said. Typically, in an interview transcript, the researcher might highlight a word, phrase, sentence, or even paragraph that describes a specific phenomenon. This word, phrase, sentence, or paragraph is a meaning unit. After highlighting this segment of text, the researcher gives it a name (code). The code should be as close to the language of the participant as possible. The difference between a code and a theme is relatively unimportant. Codes tend to be shorter, more succinct basic analytic units, whereas themes may be expressed in longer phrases or sentences. Connecting Codes or Themes into Categories After identifying and giving names to the basic meaning units, it is time to put them in categories, or families. Similar codes all can be gathered together into a category, or family of codes, and one might give them a common code. Again, stay as close as you can to the language of participants. However, as you gather codes into categories, and then categories into larger more overarching categories, you will find that you will necessarily have more abstract names for the categories in order to make them more inclusive. A good guideline is, when you move to greater abstraction, still use language that would be understandable to participants. In grounded theory, the goal would be to ultimately have all the data subsumed under one overarching core category. However, for the most part having a very few top-level categories is fine. As you code and categorize the data, also look for the interrelationships among the various categories. Searching for Confirming and Disconfirming Evidence It is easy for researchers to find data to confirm our predisposing assumptions and emerging hypotheses and to ignore data that contradict them. As we analyze data, we read and reread both to confirm what we are finding, but also to actively disconfirm. Periodically, it is helpful to take each major section of your analysis, for example a working hypothesis, and read through all the data to try to disprove it. Building a Conceptual Framework or Theoretical Model After extensive analysis, you will finally end up with an explanatory framework that describes your results. It may be helpful to the reader to see a figure with the interrelationships among the various parts of the model. In some instances, researchers reconstruct a narrative to illustrate their findings. Even as you build toward this framework, you will continue to reanalyze your data. The emerging model should be examined and reexamined, compared and contrasted with all of the data and between the various components of the model, and revised until no new changes need to be made. Just as you collected data to the point of redundancy, you are looking for a similar event in your analysis, called saturation. When all the codes and categories are saturated, that means that (a) all the data are accounted for, with no outlying codes or categories; and (b) every category is sufficiently explained in depth by the data that support it.