Psychoanalysis in Hedda Gebler

• Dildar Ahmed

Sigmund Freud

Psychoanalysis was founded by

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939). Freud believed that people could be cured by making conscious their unconscious thoughts and motivations, thus gaining insight.

The aim of psychoanalysis therapy is to release repressed emotions and experiences, i.e., make the unconscious conscious.

HEDDA GABLER AT THE TIME OF ITS

PUBLICATION

• In Hedda Gabler (1890), Ibsen lays a great emphasis on individual psychology. However, Hedda Gabler was not understood at the time of its publication. Ibsen’s portrayal of this type of a neurotic character was met with the most vehement criticisms.

• Even her Norwegian contemporaries received Hedda

Gabler as a weird character.

• A critic wrote in Morgenbladet that Hedda was ‘a monster created by the author in the form of a woman who has no counterpart in the real world’.

• It was only when the science of human behavior developed and people began to show more eagerness in the play.

HEDDA GABLER UNDER FREUDIAN

PSYCHOANALYTICAL SCANNER

• Hedda Gabler, ‘the best known of Ibsen’s creations apart from Nora Helmer’.

• Ibsen intended Hedda Gabler to be portrayed in the play more as the General’s daughter than as Tesman’s wife.

• Her father taught her all kinds of masculine acts like riding horses and firing pistols instead of preparing her for wifehood or motherhood.

• In the play, she is found playing with her father’s pistols, a possible Freudian ‘phallic symbol’ which shows her latent wish to be a man. Thus, she wishes to shove away all feminine ways.

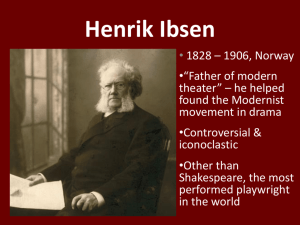

• Ibsen can only be understood in the context of the Norwegian literary culture he grew up with .

• Ibsen was in many respects an anti-Romantic. But if there is one truth which has emerged clearly from the age of theory

(Psychoanalysis) it is that no text can be finally enclosed in a single defining and exclusive context.

• For in reality both his general approach to Ibsen's plays and his detailed interpretations of them would be unthinkable had Freud never written.

• Ibsen, like Freud, is an archaeologist of the psyche. It is in fact something of a regular feature of critical writing on Ibsen that where the critic feels impelled to distance himself from.

• psychoanalysis (as several do), the Freudian infection will nevertheless be seen to have invaded his text in one surreptitious fashion or another.

REPRESSION

• But being a woman with a strict compliance to social conventions, she cannot become the sort of person she wishes to be.

• Thus, her unfulfilled desires are repressed and she keeps on yearning for things she can never attain.

• This psychological ‘repression’ ultimately makes Hedda Gabler a ‘neurotic.’

DEPRESSION

• With this mental unbalance, she grows up into a handsome young woman. And as she becomes advanced in age, she starts to suffer from depression.

• Finally, when Tesman proposes, she accepts readily on the basis that Tesman is almost sure of being appointed as a professor. Hedda sees only the money that Tesman will get from such a lucrative post.

• However, Tesman’s expected post of professorship keeps eluding him. This means that Hedda could not get enough money to enjoy the kind of life she wants.

• Her life becomes more and more boring. Her personality keeps on deteriorating day by day.

OEDIPUS COMPLEX

• Hedda, in spite of all her discontent, remains obsessed with the image of conventional woman, probably because of the strict compliance to social conventions.

• Thus, she can only complain about her marriage but she does not have the courage to leave Tesman.

• In this connection, it would be apt to state that she suffers from ‘Oedipus complex’ or rather ‘Electra complex.’

• None of the flirts surrounding her, as also her husband, were as charismatic as her father.

• In this play, Ibsen shows that Hedda’s ‘suppression’ of her desires affects her behavior throughout the play.

HYSTERIA & TRANSFERENCE

• Hedda’s ‘hysteria’ is the reaction to her female roles to which she is unsuited. Hedda rejects marriage and pregnancy but it does not mean that she achieves the way of living she wants and thus she becomes very

• depressed.

• Hedda’s resentment is directed towards others in the form of hatred, violence and destruction, which is a form of ‘transference.’

‘Transference,’ according to Freud, is the redirection of feelings and desires retained from childhood towards a

• new object.

• She hates all those who could achieve those desires she cannot attain. So she tries to manipulate the lives of others to ruin them.

NEUROSIS

• Harold Clurman said, ‘the neurotic temperament, the frustrated, the physically or morally unsatisfied often sees beauty in destruction’.

• Hedda’s complete unwillingness to accept responsibility is one of the biggest aspects of her neurosis.

• Hedda is not in a right frame of mind as she thinks that she can marry but should not get pregnant.

• Her burning of Lovborg’s manuscript which she refers to as

• Mrs. Elvsted’s child is the manifestation of her desire to kill her own child.

• Hedda is more dangerously neurotic than Nora because while Nora only leaves behind her children, Hedda vehemently avoids the very notion of childbirth and murders her unborn child by killing herself.

PLOT AND THEMES OF THE PLAY

• Central character, who is seen in some qualified sense at least, as an existential, or romantic, or tragic heroine. Hedda Gabler, it seems, presents us with a particular version of 'liberal tragedy', that form in which the claims of an alienated individual are uncompromisingly asserted against those of a conventional society .

• At the age of twenty nine, and having 'danced herself out', the aristocratic Hedda Gabler has married Jørgen

Tesman, an indefatigable scholar and pedant. If

Tesman's world seemed to offer her some sort of security, in the event she feels that she is suffocating in middle class atmosphere.

• The action of the play is presided over by the portrait of Hedda's father, General Gabler, which now hangs in the Tesmans' drawing room.

• This portrait of Hedda's dead father serves as the symbol of a military-aristocratic world which no longer offers his daughter a home. Of her mother we hear no mention at all, and Hedda's only other remaining connection with the world she comes from is the pair of pistols which she has inherited from her father.

• habit of firing off these pistols, from time to time, dramatises the profound dissonance between herself and her present world, and her frustration with the emptiness of her life.

• During the opening scenes of the play various hints are thrown out to suggest that Hedda is pregnant, but the prospect of motherhood is so far from providing her with a reason for living that it seems to be anathema to her. Certainly the child would be born into an unpromising environment, for throughout the play we have the utmost difficulty in thinking of Hedda and Tesman as a parental couple. Tesman's naïve assumption that they have everything in common is matched by Hedda's inward belief that they have nothing. The struggle to constitute the parental couple is one of the play's deep preoccupations.

• Complications unfold when we learn that

Hedda herself has had an earlier relationship with Løvborg, which broke up when she threatened to shoot him.

• Løvborg had in some undisclosed fashion begun to ask too much of the relationship.

IMAGINING THE CHILD

• Commentators are preoccupied with the character of the protagonist, her supposed revolt against 'middle class society', the authenticity or otherwise of her final action, and hence the validity of her claims to heroic status.

• The protagonist of Ibsen's play is for all of us a deeply troubling dramatic creation - outside of

Shakespeare and the Greeks

• It is believed that Hedda also displays 'serene self-confidence' is simply astonishing, for what is Hedda Gabler if not a deeply troubled soul?

TRIANGULAR PATTERNS

• The book-child theme is embedded in the more overt drama of sexual liaisons and rivalries, for example, in that the various couplings suggest a range of possibilities as to the parentage of the 'child'. And because the play generates so many different 'subject positions', in this and other ways, we come to feel that it is being staged in some figurative space in which the potentialities of human nature are being very profoundly explored.

• To ignore this theme is to turn aside, understandably perhaps, from some of the deepest unconscious fears, phantasies and anxieties which the play arouses: that if we surrender to some of our darkest impulses, for instance, we may destroy everything that is good in the world. It is also, at the same time, to miss the way in which the book-child theme shapes the structure of the play as a whole. Throughout Hedda Gabler there is a triangular patterning which has been given remarkably little attention, despite the fact that it is very prominently highlighted during the scenes between Hedda and Brack:

JEALOUSIES

• The relationship between Hedda and Brack - a sterile and destructive sparring between egotisms - which has no reference at all to the theme of the 'child'. From Hedda's marriage to

Tesman, to the relationship formed during the closing scene by Tesman and Mrs Elvsted (with a view to their resurrecting Løvborg's book-child) each liaison is shaped by this second 'triangular' theme - that is to say, the parental couple with their embryonic offspring.

THE PRIMAL SCENE

• Freud noted that the primal scene is felt by the child to be sadistic in nature, but he did not explain this finding.

Freud's 'primal scene

• Freud's 'primal scene' figures in the play - haunts it indeed, from beginning to end.

• The opening exchange of the play, between Tesman's Aunt Julle, and his servant Berte, notify us that the young couple, Jørgen

Tesman and Hedda Gabler, having returned the previous evening from a six month honeymoon trip, are still in bed, though it seems to be quite late in the morning. These events, especially as they are spoken of by these two good-hearted and motherly women, are natural enough in themselves, but everything which subsequently happens in the play serves to make the nature of the sexual relationship between the off-stage couple (which is of course variously constituted) a source of great perplexity for the

'spectator' both on and off the stage, this of course being the essence of the primal scene experience.

CREATIVITY, ENVY AND DESTRUCTIVENESS

• The dramatis personae in Hedda Gabler can rather crudely be classified in two categories - the concerned (Thea

Elvsted, Tesman, Aunt Julie, Berte) and the demonic

(Løvborg, Brack, Hedda).

• Creativity would be realised in the marriage of imagination and concern, then this union seems to be

(almost) beyond the play's conceiving, for within the collective psyche of the play imaginative energy seems to be entirely dissociated from concern and inseparably linked with ruthlessness. It is clear in fact that the sense of creative potentiality which the play generates is matched, if not overborne, by a will to destruction which threatens to leave us with nothing but its own epitaph to contemplate.

• the treatment of human destructiveness in

Hedda Gabler presents us with a remarkable anticipation of Melanie Klein's writings on the theme of envy.

• From a Kleinian point of view the choice of alcoholism as the weakness of character which Hedda is able to exploit - in order to wreak havoc upon the relationship between Løvborg and Thea - is by no means an arbitrary one. If it is obvious enough that Thea

Elvsted plays the part of the good mother who literally weans

Løvborg, lovingly, from his addiction, how is Hedda Gabler's cruel exploitation of that addiction to be understood? Like a number of other accounts of her motives which she puts forward, Hedda's claim that in driving Løvborg back to drink she is liberating him clearly lacks authenticity.

• Gnawed by her emptiness Hedda gives herself the phantasy

'satisfaction', through her identification with Løvborg, of both greedily consuming and wreaking vengeance upon the frustrating good object.

HEDDA GABLER, JØRGEN TESMAN

AND THE MASKS OF ENVY

• The stereotypical reading of Hedda Gabler, which sees Tesman, with his relatives and household, as representing a claustrophobically bourgeois complacency and Hedda, by a simple antithesis, as the imprisoned spirit of authentic protest makes the real complexities of Ibsen's play impossible to discern.

• A particular cause of envy is the absence of it in others. The envied person is felt to possess what is at bottom most prized and most desired - and this is a good object, which also implies a good character and sanity. Moreover the person who can ungrudgingly enjoy other people's creative work and happiness is spared the torments of envy, grievance and persecution. Whereas envy is a source of great unhappiness, a relative freedom from it is felt to underlie contented and peaceful states of mind - ultimately sanity.

• The subject of envy comes up at a crucial moment in one of the scenes between Hedda and Tesman, when Tesman is about to reveal that he has Løvborg's manuscript in his possession. Before revealing this he makes clear in his own way how much the book has impressed him:

FATE OR DESTINY?

• Why is Hedda Gabler so preoccupied with style? Why is the aesthetic of suicide of such importance to her?

And how are we to judge this final action of hers? If

Hedda is bidding for the full tragic effect, does the setting of her action after all render it grotesque, absurd, overblown? Is she in the wrong play - a tragic heroine framed by the elements of farce? When the curtain falls, has the play's heroine brought about a transformation of her life, or been mocked in the attempt? Imposed her own poetic shape upon her life and circumstances, or lent herself, in the endeavour, to scandal and derision - or mere incomprehension?

FATE AND DESTINY

• Embedded in this metaphor is the issue which haunts our thinking about psychoanalysis and literature. Does psychoanalytic interpretation commit us to the idea that literary characters (and real human beings) are to be seen, necessarily, as acting out a script which is always already written?

CONCLUSION

• The play deals with the story of a woman who is torn with an inner conflict between her unfeminine cravings on the one hand and her journey along the feminine path of marriage and pregnancy on the other.

• She is portrayed as a woman who cannot find her own identity.

• And in her quest for identity, she ends up killing herself.