Jacek Barszczewski - Transition Economics and Hyperinflation - A learning-based approach in the case of Poland

advertisement

Transition Economics and Hyperinflation A learning-based approach in the case of Poland

Jacek Barszczewski

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

January 27, 2019

Abstract

This paper examines the persistence of inflation in Poland during

the transition period from socialist to market economy. It will be argued, that roots of this persistence could be found in a long process

of agents adjustment to new market conditions. To explain the character of this process, a model with restricted rational learning will be

implemented. However accounting for results, it is concluded that the

basic learning model poorly reproduces the volatility of the price level.

Thus, probably further extension of the model are needed.

Keywords: Poland, transition, hyperinflation, learning

1

Introduction

In the second half of the 80’s Poland was in a deep crisis. The socialist

economy turned out to be extremely inefficient. Shortages, long queues,

strikes were a common sight. The collapse of the Iron Curtain and a set

of reforms introduced at the beginning of 90’s brought Poland back to the

developing path. The economy was stabilised within a relatively short period

of time. Thanks to launched reforms, on the cups of the new century Poland

was ready to become a member of the European Union. However, not all its

problems were solved. Despite of radical reforms in 1990, inflation in Poland

seemed to be persistent[7]. The price level was still significantly higher than

the EU average, which was around 3%. Moreover, the inflation in Poland

was between 7% and 15% in the last years of 90’s.

Using monthly data from 1990(1) to 1999(12), this paper sets out to

investigate the persistence of inflation in Poland. Results of estimation are

thought to provide answer for the following question: can we explain the long

period of high inflation by high levels of seniorage? Does learning processes

explain the persistence of inflation in Poland? Can we assume that agents

had a restricted rational learning model? Learning was introduced to verify

above-mentioned hypothesis by using modification of the model proposed

by Marcet and Nicolini[10] for South America countries. The outcomes of

the model is discussed to answer to formulated hypothesis.

This paper is organised as follows. Section II discusses the roots of

hyperinflation in Poland and reviews literature on the transition process

from socialist to market economy with a focus on the explanation of inflation

persistence. Section III presents the theoretical framework of the model that

is used to determine Polish inflation empirically. Section IV discusses sources

of the data used for the model and presents results of the simulation. Section

V concludes with a discussion.

1

2

Roots of hyperinflation in Poland and reforms

of transition process

One of the symptoms of late 80s crisis in Poland was constantly fast increasing prices. As Kolodko et al.[8] noticed, an inflation in a socialist economy is

characterised by a duality - it consists of a general rise of price level typical

for market economies and shortages typical for socialist economies. This

phenomenon is called shortageflation in the literature [9].

In the Polish case there were several factors which led to hyperinflation1 .

Firstly, the rise of prices was accelerated by an execution of a ”price-andincome” operation in February 1988. Instead of reduction in average real

wages, the latter were increased. In the light of common shortages, those

operation has only ”statistical” nature. As a result, strong pressure on prices

appeared because of an excessive labour cost. Another factor are the result

of the Round Table negotiations - ”makretization” of agriculture and ”the

general wage and income indexation system”. The ”marketization” of the

agriculture mainly consisted of a liberalisation of retail prices of food, which

were artificially depressed by government in socialist economy. The price

level acceleration was additionally fuelled by the effect of full indexation.

There was also another additional accelerator of inflation. A retroactive

rise of state purchases prices for agriculture products caused a breakdown

in public finance. It rapidly worsened the situation of the state budget. As

Kolodko at al.[8] pointed out inflationary budget expenditures were excessively growing, especially for subsidies to the state sector production. On

the other hand, budget revenues were lowered by a weak fiscal discipline.

The government deficit was nearly 8% and both loss-making Polish companies and the government deficit were financed by the rapid expansion of

money and credit.

Above-mentioned factors led to a sharp increase of inflation during the

summer 1989, when the consumer price index soared to 55% - figure 1. The

situation got even worse at the beginning of 1990, when in January the

inflation hit a peak amounting nearly 80%. Deep financial and social crisis

together with the soaring inflation forced the new-formed government in

autumn ’89 to take radical steps. A major stabilization began on January

1, 1990 with the introduction so-called Balcerowicz Plan. The plan consisted

of several components[16]: changes in a monetary and fiscal policy, further

liberalization of prices, an introduction of a convertibility of zloty and a

restrict revenue policy.

The main goal of reforms in monetary policy was to slow down the increase of nominal money supply and increasing nominal interest rates. Addi1

The use of term ”hyperinflation” in the context of inflation in Poland in ’90s during

the transition period still seems to be controversial. Accuracy of a usage of this expression

depends on the assumed definition. However, in the light of the outgoing debate I propose

to use ”hyperinflation” term here

2

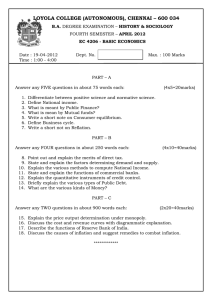

Figure 1: Inflation from Apr-89 to Sep-90 (previous month = 100)

tionally, financing of the deficit by National Bank of Poland (Polish Central

Bank - NBP) was strictly limited. The NBP also gained wider independence of the government. In fiscal policy the main change was a reduction

of the deficit from 8% of GDP in 1989 to 0,8% in 1990[8]. The significant

decrease was mainly obtained by cuts in subsidies and state investments.

”The general wage and income indexation system”, introduced as a result

of the Round Table, was lifted. Instead, the new tax (so-called popiwek ) on

increase of wage fund was introduce.

The key role in the process of fighting with hyperinflation was devoted

to the National Bank of Poland. One of the most powerful tools, which were

used, was introducing a fixed exchange rate policy. During the communism

period there were two foreign exchange market in Poland. An official one

controlled by the government and an unofficial one controlled by a network

of touts. The official exchange rate of PLN/USD was permanently strongly

understated. This led to the situation in which the size of the black market

was bigger than the official one (up to 7 times)[6]. In January 1990 the

exchange rate PLN against the dollar was made real and a fixed exchange

rate was implemented[1]. In the next step in May 1991 a fixed rate against

a basket of five currencies was introduced. Crawling peg with monthly rate

of devaluation declining steadily from 1.8% to 1.2% was conducted in the

3

period between October 1991 and May 1995. As a next step of liberating

the exchange rate, the NBP introduced a crawling band system, with a

fluctuation band increasing from ±7% to ±15%. The last point of the reform

was the introduction of a free-floating exchange rate system in May 2000.

The implementation of the Balcerowicz Plan brought fast effects, especially in monetary policy. After a few months the price index stabilized

on a moderate level. What is more, it was done together with keeping the

austerity in fiscal policy. In 1990 the budget was closed with a surplus

amounting 0.7% of GDP[8]. However, when times went by new economic

problems loomed. The recession turned out to be deeper than reforms authors assumed. Polish society after the communism period was not ready to

face unemployment problems characteristic for markets economies. What is

more, inflation turned out to be more persistent then it had been thought

before - see figure 2.

Figure 2: Inflation in 1989-1999

There are several researches which tried to explain the persistence of

inflation in Poland[7]. Welfe[19] was investigating the cointegration relationship between prices and wages. He claimed that the dominant factor

generating inflation in Poland between 1991 and 1996 was a raise in wages.

An opposite explanation was provided by Brada and Kutan[3]. In their

paper they used causality tests and a variance decomposition method to

4

analyse the roots of inflation in three transition countries: Poland, Czech

Republic and Hungary. Nominal wage growth and money supply turned out

be unimportant contributors to the inflation process in the short run. Brada

and Kutan argued that there are three main factors influencing the inflation

process: foreign prices, exchange rate and past path of the process, which

can be interpreted as an inflationary expectation of the population.

Mass et al.[11] among causes of inflationary expectations persistence

named: government’s use of the central bank or of commercial banks to

finance deficit, high initial value of inflation (excess of 10%) and a failure to

combat the fiscal roots of inflation. As Brada and Kutan[3] suggested, all

of these factors one can find to a greater or lesser extent in each of three

analysing by them transitions countries.

3

3.1

A Theoretical Framework of the Models

Baseline model

The basic assumptions of the model are similar to those made by Marcet

and Nicolini[10]. The model consists of a set of equations, which determines

the demand for real balance and the government budget constrain relating

money creation and changes in international reserves of the central bank.

In the paper, it is assumed that the demand for real balance is given by

the following equation:

Pe

MtD

= φ − γφ t+1

Pt

Pt

(1)

e

where MD

t is a nominal demand for money, Pt is price level in period t, Pt+1

is agents expectation in period t for the price level in period t+1. δ and λ

are given parameters.

Similarly, under the assumption of a floating exchange rate, the government budget constrain is given by the following equation:

Mt = Mt−1 + dt Pt

(2)

where dt is a real value of a seigniorage. The seigniorage is defined in this

model as difference between nominal money supply in period t and period

t-1. In this model seigniorage is the only source of financing deficit by

government. Equations (1) and (2) together with the hypothesis of agents

expectations determines the sequence of values for {Mt , Pt }∞

t=1 in periods

with the fixed exchange rate.

However, as it was mentioned before, in analysing the period in Poland

fixed exchange rate was introduced. It means, that the central bank was

trying to keep the inflation in Poland equal to the foreign inflation. In

this case it is needed to change the equation for the government budget

5

constrain. The money demand given by equation (1) will not match money

supply given by (2). Following Marcet and Nicolini[10], in this paper it is

assumed that as it is in a standard fixed exchange model, the central bank is

adjusting international reserves to achieve the right level of money balances.

In this case, instead of money supply given by (2), it is given by the following

equation:

Mt = Mt−1 + dt Pt + et (Rt − Rt−1 )

(3)

where et is an exchange rate in a period t and Rt is a nominal value of

international reserves in a period t. Equations (1) and (3) together with

hypothesis of agents expectations determine the equilibrium values for {Mt ,

Pt }∞

t=1 in periods of floating exchange rate.

3.2

Model with Restricted Rational Learning

The model of restricted rational learning used to explain persistence of inflation in Poland in 1990’s is based on the model proposed by Marcet and

Nicolini[10] to explain the phenomenon of recurrent hyperinflation in South

American countries in 1980’s. In the model it is assumed that using information from the past agents learn about the inflation process:

e

Pt+1

= βt

Pt

(4)

Following Marcet and Nicolini[10], the paper assumes that the learning

mechanism is given by the stochastic approximation algorithm:

βt = βt−1 +

1

(πt−1 − βt−1 )

αt

(5)

for given β0 . This stochastic approximation can be interpreted as perceived

inflation βt is updated by the term that depends on the last prediction error.

The last prediction error is weighted by the gain sequence α1t . Equation

4 together with the assumption about the evolution of α1t determines the

learning mechanism introduced into the model.

There are two standard assumption for the gain sequence. The first

one is αt = αt−1 + 1. This assumption cause that learning process is an

equivalent of the OLS estimator of the inflation mean. In this case αt = t,

so the learning algorithm can be rewrite as:

t

βt+1

1 X Pi

=

t

Pi−1

(6)

i=1

From the equation (6) it can be concluded that OLS gives equal weights to

all past observation. It makes this algorithm predict inflation ”well” during

6

the stability period, because it ignores small shocks. On the other hand,

forecasts generated by least squares are ”wrong” during the hyperinflation

period, because it is extremely slow in adapting to the rapidly changing

price level.

The second standard assumption for the gain sequence is called ”constant

gain”. In this case αt is constant over time and equal ᾱ. In this case, an

equation for a perceived inflation can be rewritten as:

t

βt+1

1X

1 Pt−i

=

(1 − )i

ᾱ

ᾱ Pt−i−1

(7)

i=0

Following Marcet and Nicolini[10] a learning mechanism used in this

paper mixes both alternatives: OLS and ”constant gain”. OlS will be used

in periods with stable inflation while constant gain will be introduced when

instability appears. It means that as long as agents are not making large

mistakes they use OLS algorithm. If the large mistake is detected then they

introduced ”constant gain”. Formally, described condition can be expressed

as follows:

αt = αt−1 + 1 if |

πt−1 − βt−1

|<v

βt−1

(8)

= ᾱ otherwise

Using equations (1), (3) and (4) it can be shown that the gross inflation

rate at time t is equal:

πt =

φ − γφβ̂t−1 + et (Rt − Rt−1 )/Pt−1

φ − γφβ̂t − dt

(9)

Equation (9) implies that inflation in the model is well defined only if at

each t nominator and denominator are positive (otherwise the real balances

demand could become negative). However, there is no restriction within

the model preventing these constraints from being violated. What is more,

equation (9) implies that the price level is not bounded[2]. Given the numerical problems that this can generate when estimating the parameters, it

is assumed that there exists constants δ U , δ L > 0 such that δ L < πt < δ U

for every t. Those two constrain can be rewritten as follows:

(φ − γφβ̌t − dt ) > 0 and

δL <

φ − γφβ̂t−1 + et (Rt − Rt−1 )/Pt−1

φ − γφβ̂t − dt

< δU

(10)

If any of those constraints is violated than equation (9) does not longer determine the level of inflation. In this case, it is assumed that the central bank

7

tries to keep the inflation from the previous period. So, πt is determined

randomly by the following normal process:

πt ∼ N (πt−1 , σ)

(11)

The proposed process for the inflation in period, when constrains for learning

process are violated, is based on proposal made by Pincheira and Medel[15].

In their paper they showed via simulations that persistent stationary inflation processes may be well predicted by unitroot-based forecasts.

The above system of equations fully described the performance of the

model with restricted rational learning.

4

4.1

A Estimation of the Models

Data

A data set consisting of monthly observation of the consumer price index

(CPI)[17], the narrow nominal money supply (M1)[14], the international reserves of NBP[13] and the nominal gross domestic product[18]. Specifically,

the letter one was expressed in Special drawing right. The exchange rate

XDR/USD[5] and USD/PLN[12] was used to express the international reserves of NBP and gross domestic product (GDP) in Polish zloty (PLN). The

sample period runs from 1990 to 1999. All data is taken from the OECD

data set, except CPI which was taken from Statistics Poland, GDP which

was taken from The World Bank and XDR/USD exchange rates which was

taken from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. All estimations were

carried out using the Matlab R2018b software package.

4.2

Estimation results

To generate estimation, values should be assigned to parameters of money

supply (φ, γ) and lower and upper bounds of the inflation process (δ U , δ L ).

The value of the parameters (φ = 0.92, γ = 0.09) were chosen based on the

sequence of Monte Carlo simulation in order to replicate some patterns of

the Polish inflation. The value of lower and upper bounds was arbitrary

chosen as δ L = 0.95 (the central bank doesn’t want to allow for deflation

higher than 5% per month) and δ U = 1.8 (the central bank is trying to avoid

the hyperinflation from January ’90 onwards).

If any of constrains is violated, then inflation is normally distributed

with mean equal πt−1 and variance equal variance of the inflation in data

(σ = 0.0057). The parameter v, following Marcet and Nicolini[10], was set

equal to 10 percent.

To replicate the original process of inflation in Poland, initial believes of

agents were chosen to equal inflation in the previous period. Similarly as it

8

was in Marcet and Nicolini[10] the process for αt under the assumption of

”constant gain” is set to α̂ = 5.

Figure 3 presents results of the estimation of CPI in Poland by a model

with restricted rational learning. An average of CPI simulation is significantly higher than in data - table 1. The CPI in model simulation does not

follow a slow, but decreasing process as it is in the data. There are a lot

of variabilities in the simulation outcome. The price level has a constant

tendency to grow. The variance of the CPI process is also much higher than

in data. To sum up, the outcome of the simulation does not illustrate the

volatility of CPI in Poland. The model with restricted rational learning does

not explain the persistence of inflation in Poland.

Figure 3: Real data and model estimation of CPI

Real data

Model simulation

mean

1.0302

1.1637

variance

0.0057

0.0311

max

1.7960

1.7960

min

0.9910

0.9519

Table 1: The results of Monte Carlo simulation for the model with restricted

rational learning

9

5

Conclusions

The model with restricted rational learning poorly performs in the case of

Poland. The path of inflation generated by the model is characterised by

a significantly higher mean. When it comes to the variance, the outcome

of the model is even worse - the inflation process generated by the model

volatilities 6 times more than the real inflation process.

There are several possibilities, which probably contributed to the failure of this model. Cukrowski et al.[4] concluded that there was a weak

relationship between inflation and seniorage. It means that the theoretical

basis of the model could be not sufficiently strong in case of Poland. What

is more, Brada and Kutan[3] showed using a VAR model, that monetary

policy conducted by the NBP was rather quantitatively unimportant as a

factor influencing the price level.

However, there are several possibilities to extend the model to obtain

more satisfying results. First of all, as Brada and Kutan[3] noticed, the

import prices and changes in nominal interest rates had a important role

in creating transitory shocks. Their founding was based on analyses of a

VAR model system. Probably extending the model by import prices and

changes in nominal interest rates can significantly improve the outcome of

the model. Another proposition of an extension of the model was made by

Sámano et al. [2], who analysed inflation in Mexico. In their paper, they

added to the model changes in exchange rates. This extension significantly

improved outcome of the model. It is recommended to analyse if aforementioned extensions could significantly influence the outcome of the model with

restricted rational learning.

References

[1] Banbula, P., Kozinski, W., and Rubaszek, M. The role of the exchange rate in monetary policy in poland. In Capital flows, commodity

price movements and foreign exchange intervention, B. f. I. Settlements,

Ed., vol. 57. Bank for International Settlements, 2011, pp. 285–295.

[2] Bernabé, L.-M., de Aguilar Alberto, R., and Daniel, S. Fiscal Policy and Inflation: Understanding the Role of Expectations in

Mexico. Working Papers 2018-18, Banco de México, Oct. 2018.

[3] Brada, J., and Kutan, A. The end of moderate inflation in three

transition economies? ZEI Working Papers B 21-1999, University of

Bonn, ZEI - Center for European Integration Studies, 1999.

[4] Cukrowski, J., Ed. Renta emisyjna jako źródlo finansowania budżetu

państwa, vol. 42. Center for Social and Economic Reserach, 2001.

10

[5] Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis. National Currency to US

Dollar Exchange Rate (Average of Daily Rates for the International

Monetary Fund). https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series, 2019. Online; accessed 09 January 2019.

[6] Gruszczynski, M., and Stoklosa, M. Effectiveness of unofficial

currency market in poland in 1982-1989. Bank i Kredyt, 9 (2003), 33–

46.

[7] Kim, B.-Y. Modeling inflation in poland: A structural cointegration

approach. Eastern European Economics 46 (11 2008), 60–69.

[8] Kolodko, G. W., Gotz-Kozierkiewicz, D., and SkrzeszewskaPaczek, E.

Hyperinflation and Stabilization in Postsocialist

Economies. International Studies in Economics and Econometrics 26.

Springer Netherlands, 1992.

[9] Kolodko, G. W., and McMahon, W. W. Stagflation and shortageflation: A comparative approach. Kyklos 40, 2 (1987).

[10] Marcet, A., and Nicolini, J. P. Recurent hyperinflation and learning. The American Economic Review 93, 5 (2003), 1476–1498.

[11] Masson, P., Savastano, M. A., and Sharma, S. The scope for inflation targeting in developing countries. IMF Working Papers 97/130,

International Monetary Fund, 1997.

[12] OECD. Exchange rates. https://data.oecd.org/conversion/exchangerates.htm, 2019. Online; accessed 09 January 2019.

[13] OECD. Goverment reserves. https://data.oecd.org/gga/governmentreserves.htm, 2019. Online; accessed 09 January 2019.

[14] OECD.

Monetary Aggregates (Narrow Money M1).

https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?QueryId=29809, 2019.

Online;

accessed 09 January 2019.

[15] Pincheira, P., and Medel, C. Forecasting Inflation With a Random

Walk. Working Papers Central Bank of Chile 669, Central Bank of

Chile, July 2012.

[16] Skrzyński, T. Hyper-inflation counteracting programmes - wladyslaw

grabski’s and leszek balcerowicz’s reforms. Zeszyty Naukowe / Polskie

Towarzystwo Ekonomiczne 2 (2004), 73–90.

[17] Statistics Poland.

CPI.

http://stat.gov.pl/obszarytematyczne/ceny-handel/wskazniki-cen/wskazniki-cen-towarowi-uslug-konsumpcyjnych-pot-inflacja-/miesieczne-wskazniki-cen11

towarow-i-uslug-konsumpcyjnych-od-1982-roku/,

accessed 09 January 2019.

2019.

Online;

[18] The

World

Bank.

World development indicators.

https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/world-developmentindicators, 2019. Online; accessed 12 January 2019.

[19] Welfe, A. Modeling inflation in poland. Economic Modelling 17 (02

2000), 375–385.

12