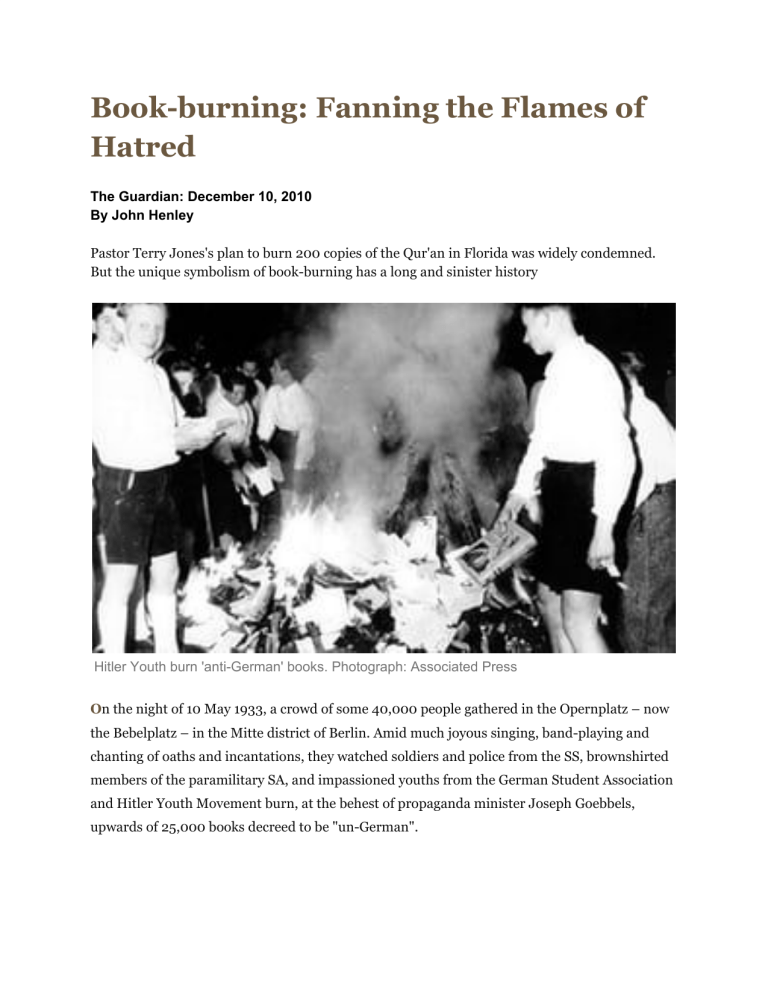

Book-burning: Fanning the Flames of Hatred The Guardian: December 10, 2010 By John Henley Pastor Terry Jones's plan to burn 200 copies of the Qur'an in Florida was widely condemned. But the unique symbolism of book-burning has a long and sinister history Hitler Youth burn 'anti-German' books. Photograph: Associated Press On the night of 10 May 1933, a crowd of some 40,000 people gathered in the Opernplatz – now the Bebelplatz – in the Mitte district of Berlin. Amid much joyous singing, band-playing and chanting of oaths and incantations, they watched soldiers and police from the SS, brownshirted members of the paramilitary SA, and impassioned youths from the German Student Association and Hitler Youth Movement burn, at the behest of propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, upwards of 25,000 books decreed to be "un-German". The climax of a month-long nationwide campaign, this best-known of literary bonfires was intended as both a purge and a purification of the true German spirit, supposedly weakened and corrupted by un-German ideas and intellectualism. "The future German man," the Reichsminister declared in a speech, "will not just be a man of books, but a man of character. You do well, in this midnight hour, to commit to the flames the evil spirit of the past. From this wreckage the phoenix of a new spirit will triumphantly rise." The volumes consigned to the flames in Berlin, and more than 30 other university towns around the country on that and following nights, included works by more than 75 German and foreign authors, among them (to cite but a few) Walter Benjamin, Bertolt Brecht, Albert Einstein, Friedrich Engels, Sigmund Freud, André Gide, Ernest Hemingway, Franz Kafka, Lenin, Jack London, Heinrich, Klaus and Thomas Mann, Ludwig Marcuse, Karl Marx, John Dos Passos, Arthur Schnitzler, Leon Trotsky, HG Wells, Émile Zola and Stefan Zweig. Also among the authors whose books were burned that night was the great 19th-century German poet Heinrich Heine, who barely a century earlier, in 1821, had written in his play Almansor the words: "Dort, wo man Bücher verbrennt, verbrennt man am Ende auch Menschen" – "Where they burn books, they will, in the end, also burn people." There's something uniquely symbolic about the burning of books. It goes beyond the censoring of beliefs and ideas. A book, plainly, is something more than ink and paper, and burning one (or many) means something more than destroying it by any other means. Goebbels, of course, was by no means the first to recognise the symbolism: authorities around the world, both secular and religious, have known since the Chinese Qin dynasty in 200BC that book-burning is an act of peculiar potency. If Pastor Terry Jones, leader of the small but now extremely well-known Dove World Outreach Centre in Gainesville, Florida, who planned to burn 200 copies of the Qur'an despite near-universal condemnation, didn't know it before, he certainly does now. (Jones, who has received death threats, may have taken to carrying a gun, but no less a figure than Barack Obama warned yesterday of the consequences the pastor's act may have had for US servicemen in Iraq and Afghanistan.) The poet, philosopher and political theorist John Milton, whose books were publicly burned in England and France, gives perhaps the best explanation of why authorities down the centuries have seen danger in certain books. "Books are not absolutely dead things," he wrote in his celebrated attack on censorship, Areopagitica, in 1644, "but do contain a potency of life in them to be as active as that soul was whose progeny they are." Anyone who kills a man, Milton said, kills "a reasonable creature, God's image; but he who destroys a good book kills reason itself". Throughout history, says Matt Fishburn, author of Burning Books, a chronicle of the phenomenon through the ages, most official book-burnings have been about "control", to announce "what a regime stands for". Like previous such ceremonies, the Nazi burnings (which Fishburn said, on their 75th anniversary in 2008, have since become "a cultural benchmark, a popular analogy and a common insult – to burn a book today is to be a 'fascist'") were, essentially, about "announcing what would be acceptable in future; shaping the new public sphere. The burnings were the symbol; the repressive legislation that came in their wake was what really enforced it." More innocently, people have long lit celebratory bonfires to mark the end of one phase in their lives and the start of another: graduating students may burn unpopular textbooks at the end of a course; refugees celebrate naturalisation by burning their old papers. But it is as an official means of suppressing dissenting or heretical views that book-burning has acquired its infamy. The practice features prominently in two of the 20th century's more alarming novels about authoritarian future societies: Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451, in which book-burning has become institutionalised in a wholly hedonistic, anti-intellectual US, and George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four, where unapproved books and tracts are consumed by flames in a "memory hole". It also crops up in the Bible. A passage in the New Testament Book of Acts (Acts 19: 19-20) suggests Christian converts in Ephesus burned books of "curious arts", generally taken to mean traditional magic: "Many of them also which used curious arts brought their books together and burned them before all men." The earliest recorded incident of book-burning in history appears, however, to be Emperor Qin Shi Huang's order in 213 BC that all books of philosophy and history from anywhere other than Qin province in China be burned (and a large number of uncooperative intellectuals buried alive). Since then, the Ancient Greeks and Romans have burned Jewish and Christian scriptures, and any number of popes from the 13th to the 17th centuries ordered the burning of the Talmud, a fate that befell John Wycliffe's works in the 15th century and William Tyndale's English translation of the New Testament in the 16th. The Spanish Inquisition burned 5,000 Arabic manuscripts in Granada in 1499, and Spanish conquistadors burned all the sacred texts of the Maya in 1562. Luther's translation of the Bible went up in flames in Catholic parts of Germany in the 1640s, and in the 1730s the Archbishop of Salzburg oversaw the burning of every Protestant book and Bible that could be got hold of. The communists burned untold numbers of decadent western books and writings in the Soviet Union from the 1920s on, and several American libraries burned the works of supposedly pro-Communist authors during the McCarthy era. More recently, Orthodox Jews in Jerusalem burned copies of the New Testament in 1984; Salman Rushdie's The Satanic Verses was ceremonially burned in Bolton and Bradford in 1988; Harry Potter books have been burned in the US on various occasions since their first publication; and in Rome they burned The Da Vinci Code. Besides individual titles, whole libraries have been razed to the ground, some more than once: Alexandria in Egypt (by lots of people); Washington (by the British); Louvain (by the Germans); Sarajevo and, most recently, Baghdad. Why burning, though, rather than some other kind of destruction? The symbolism of flames is plain. For Andrew Motion, former poet laureate and chair of this year's Man Booker prize, "books are little encapsulations of human effort and wisdom and, I suppose, of our sense of history. So to burn one of any kind, and certainly one that is a representation of a culture and set of beliefs, is to appear to consign it to the flames of eternal damnation." Book-burning, he says, is first and foremost a monumental "manifestation of intolerance. It's the conflation of what ought to be nuanced views into one, hate-filled act." Does Pastor Jones fit this picture? There's an important difference between his plans and officially sanctioned book-burning campaigns such as those of the Nazis, says Richard Evans, regius professor of history at Cambridge and a specialist in German social and cultural history. While the book-burnings of 1933 were largely independently led by fascist students, presaging the "mass violence, real and symbolic" that was then starting to take over Germany, they were actively encouraged by the Nazi leadership in a bid to "purge the un-German spirit". Jones's International Burn-a-Koran Day is, on the other hand, an act of defiance and, in choosing to burn just one book many times over, "quite clearly a symbolic attack on Islam as a whole". Anyone who had tried to burn Mein Kampf in 1933, Evans says, "would have been arrested and shot".