DISCRETION OF STREET-LEVEL BUREAUCRATS IN PUBLIC SERVICES: A CASE STUDY ON PUBLIC HEALTH IN MAKASSAR

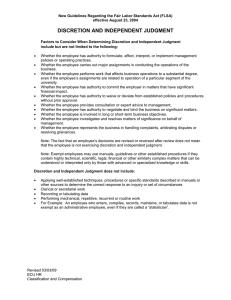

advertisement

International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology (IJCIET) Volume 10, Issue 04, April 2019, pp. 2224-2233, Article ID: IJCIET_10_04_231 Available online at http://www.iaeme.com/ijciet/issues.asp?JType=IJCIET&VType=10&IType=04 ISSN Print: 0976-6308 and ISSN Online: 0976-6316 © IAEME Publication Scopus Indexed DISCRETION OF STREET-LEVEL BUREAUCRATS IN PUBLIC SERVICES: A CASE STUDY ON PUBLIC HEALTH IN MAKASSAR Hasniati Hamzah Departement of Public Administration, Faculty of Social and Political Science, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, Indonesia. Fitriani, Vinsenco R. Serano, Albertus and Y. Maturan Departement of Public Administration, Faculty of Social and Political Science, Musamus University, Merauke, Indonesia. Muhammad Yunus Departement of Public Administration, Faculty of Social and Political Science, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, Indonesia. ABSTRACT. Street-level bureaucrats (SLBs) have a great opportunity in taking discretion in public services. This is because in the provision of services is often confronted with the scarcity of resources that are owned, so that requires them to make policies (discretion) to get around the scarcity of these resources. Discretionary authority possessed by SLBs can be a "disaster" if not used professionally and carefully, especially if it is done in the field of health services that can have a negative impact on the community served. This study aims to reveal various forms of discretion taken by SLBs in health services in Public Health Center (PHC) in Makassar City, what is the background of taking discretionary actions, as well as the impact of the discretion taken. This study uses a qualitative approach with in-depth interview data collection techniques. The number of informants interviewed was 24 people consisting of the head of the PHC, doctors, nurses, midwives, pharmacists, as well as window clerks. Data processing and analysis using the NVivo 12 Plus application. The results showed that the level of discretionary use was different for each SLBs. Courage to take discretion is strongly influenced by the experience and independence of SLBs, as well as considering the impact on patients. In general, the discretion taken solely aims to facilitate service and is based on the desire to save the lives of patients served. Keywords: Discretion, Health Services, Street-level Bureaucrat, Public Health Center \http://www.iaeme.com/IJCIET/index.asp 2224 editor@iaeme.com Hasniati Hamzah, Fitriani, Vinsenco R. Serano, Albertus, Y. Maturan and Muhammad Yunus Cite this Article: Hasniati Hamzah, Fitriani, Vinsenco R. Serano, Albertus, Y. Maturan and Muhammad Yunus, Discretion of Street-Level Bureaucrats in Public Services: A Case Study On Public Health In Makassar. International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology, 10(04), 2019, pp. 2224-2233 http://www.iaeme.com/IJCIET/issues.asp?JType=IJCIET&VType=10&IType=04 1. INTRODUCTION The main task of government is to provide public services. Bureaucrats who provide services and interact directly with the community by Lipsky (2010) are referred to as street-level bureaucrats (in this paper abbreviated as SLBs). While the bureaucracy institution where he works is called the street-level bureaucracy. Because the task is in direct contact with the community, the SLBs are seen as "moral agents," because he has greater discretionary authority in carrying out his daily duties. In terms of theory, the community expects SLBs to be role models and follow applicable laws and regulations. The amount of power and authority possessed by SLBs is not identical to the high level of bureaucratic discretion (Wibawa, 2009). Therefore, for public services, discretionary authority is sometimes required to respond quickly to community demands, while what is demanded by the public has not been regulated in certain laws or policies. In reality the law cannot possibly cover all public and government problems in real terms according to the needs of the people served, so SLBs need to take discrete actions to solve problems that occur in the field. Therefore, professional discretion is needed (Cheraghi-Sohi & Calnan, 2013; Evans, 2011). There has much debate about the extent to which professional discretion has been challenged by recent organisational changes such as through the new forms of governance associated with the introduction of the principles of the New Public Management (NPM) into health systems and other public sector services (Cheraghi-Sohi & Calnan, 2013). What was stated by Cheraghi-Sohi & Calnan (2013), and Evans (2011) became interesting to study, especially in relation to public policies and services in Indonesia. In many cases, some public officials have to deal with the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) as a result of the discretionary authority taken. This is because SLBs have to deal with service provision and translate short rules into comprehensive and specific language (Sowa & Selden, 2003). Law No. 30/2014 concerning State Administration explicitly regulates discretion. Discretion is defined in Article 1 paragraph (9) of Law No. 30/2014, as decisions and/or actions established and/or carried out by government officials to address concrete problems faced in the administration of government in terms of legislation that provides options, does not regulate, incomplete or unclear and/or there is a stagnation of government. Thus, a discretion can only be issued if the purpose of publishing the discretion is: (i) launching the administration of government; (ii) fill the legal vacuum; (iii) provide legal certainty; and (iv) addressing the stagnation of government in certain circumstances for the benefit and public interest. However, fulfilling the purpose of discretion as described above is not enough. Law No. 30/2014 requires that discretion can only be used if its use meets the following conditions: 1. In accordance with the objectives of the discretion stated in Law No. 30/2014; 2. Does not conflict with the provisions of the legislation; 3. In accordance with the general principles of Good Governance; 4. Based on objective reasons; 5. Does not create a conflict of interest; and 6. Done in good faith. http://www.iaeme.com/IJCIET/index.asp 2225 editor@iaeme.com Discretion of Street-Level Bureaucrats in Public Services: A Case Study On Public Health In Makassar In addition to fulfilling the material requirements above, a discretion is also obliged to fulfill the formal requirements stipulated in Law No. 30/2014 wherein basically government officials who use discretion must obtain supervisory approval by first describing the intent, purpose, substance and impact of administration and finance. In the case of faster public service interests, discretion is needed in situations of uncertainty along with the increasingly rapid dynamics of the development of public demands and ambiguous agency goals agency and inadequate resources (Lipksy, 2010). In these conditions, a SLBs is possible to pursue discretive policies as long as they remain in the corridor of their duties and responsibilities to answer the demands of the people served (Lipsky, 2010), but need to pay attention to the role of professionalism and the relationship between front line managers and workes and the nature of discretion (Evans, 2011). The problem is when SLBs are given a more discretionary space, then can they exercise discretionary authority responsibly, is the discretion taken by the SLBs their authority, does the discretion not contradict the provisions of the legislation, and is it really aiming for the public (public) interests served, and how far the discretionary authority can significantly increase the professionalism and quality of public services ?, what is the reason why the discretion is taken, and whether the discretion is in accordance with the Good Governance Principles ? Some of these questions will be answered in this study. This article attempts to describe the opportunities for discretion that can be done by SLBs when facing problems in health services, whether the problems are related to the resources they have or the problems associated with the insistence of patients in meeting their needs to get the services they expect. And when SLBs take discretion, whether the discretion does not conflict with higher regulations, and whether it can fulfill the general principles of good governance, especially related to the professionalism of SLBs. The last is to analyze why discretion is carried out and how the impact will be on the quality of public services. One of the tasks and responsibilities of the government is to provide services to the community. Those who are assigned to provide direct services to the community are called street-level bureaucrats, SLBs (Lipsky, 2010). In carrying out service duties, SLBs often take discretion for the purpose of providing fast service, so that by Lipsky (2010) states that SLBs are discretion policy makers. The essence of the concept of discretion is freedom in making a decision. The freedom to make decisions regarding the services provided by SLBs is certainly limited by several factors. Some of the earliest discussions regarding the nature of discretion, originated within the legal arena (Cheraghi-Sohi, 2013). In the development of public administration theory, discretion or often referred to as administrative discretion is the ability of administrators to choose between alternatives courses of action (Evans, 2011) and decide how a government policy must be implemented in certain situations (Lipsky 2010, Mangkoedihardjo, 2014). In line with that, Rabin (2003) and Cann (2007) suggested that administrative discretion, referring to the implementation of flexible assessments and decision-making that are made public administrators (in this article called street-level bureaucracy, SLB) has the authority to apply discretion in their daily activities, but in the course of time, these bodies often abuse this authority. The need for discretion is still needed for the public interest, but it will be very dangerous when SLBs use it arbitrarily which can lead to the destruction of the basic principles of administrative law (Vaishnav & Marwaha, 2015). Therefore discretion in public services is carried out solely to fulfill the public interest (Barth, 1992) and should not be contrary to the law and wider public interest (Scott, 1997) and for performance improvement (Ortega, 2009). http://www.iaeme.com/IJCIET/index.asp 2226 editor@iaeme.com Hasniati Hamzah, Fitriani, Vinsenco R. Serano, Albertus, Y. Maturan and Muhammad Yunus Thus, in using discretionary authority, SLBs must not be arbitrary and what they do must be reasonable in order to fulfill the principles of good governance. The theory used in this study is a framework developed by Lipsky (2010). Although Lipsky's (2010) theory was developed in the American context, Lipsky believes that this theoretical framework can be applied to all public services, including health services in the PHC in this study. Lipsky (2010) defines street-level bureaucracy as a bureaucracy that interacts directly with the people served such as PHC, Civil Registry Offices, and District Offices in providing services to the community. While the working bureaucracy is referred to as the street-level bureaucrats. Street-level bureaucrats are the main actors in implementing public policies and services. It is the most important variable in the success of policy implementation. These bureaucrats are storefronts of a bureaucracy that can influence people's perceptions and views of the policies implemented. Where this is highly dependent on discretion and interpretation of street-level bureaucrats in implementing a policy Street-level bureaucrats implementing public policies have a certain degree of autonomy – or discretion – in their work (Tummers & Bekker, 2014). Discretion and interpretation of policies are carried out to answer the challenges and demands of various backgrounds of the people served, ranging from people who have no education at all to the educated community. Conditions like this require special treatment in policy implementation, whereas a policy is usually general in general. That is where discretion and interpretation of a policy becomes a necessity for SLBs. The PHC, is a health service facility that organizes public health efforts and first-rate individual health efforts, prioritizing promotive and preventive efforts, to achieve the highest degree of public health in its working area. PHC are frontline bureaucracies because they interact directly with the community (patients) in providing services. The bureaucrats who work in the PHC are referred to as frontline bureaucrats, namely the Head of the PHC, Doctors, nurses, fields, pharmacists, and window clerks. They deal directly with patients in carrying out their daily tasks. In the situation of limited resources such as medical equipment, medicines, a wider range of services, the SLBs at this PHC have the authority to make decisions or discretion so that the services provided can be faster and satisfy the patients served. 2. METHODS This research was conducted at the PHC Makassar. PHC is street-level bureaucracy due to direct interaction with the community in providing health services. A total of 24 SLBs were interviewed in 4 PHC in Makassar City in the period June - September 2018. Four people were line managers (Head of PHC), and the rest were SLBs namely doctors, midwives, nurses, pharmacists, and window clerks. The criteria used to determine the informants are those who have worked for at least one year, so that they have experience in making discretion in the services they provide (Alexander et al., 2018; Elisabeth et al., 2018; Philipus Betaubun and Nasra Pratama Putra, 2019; Supriyadi et al., 2019). The research approach is descriptive-qualitative which aims to provide an overview of the discretionary phenomena taken by SLBs in providing services to the public (community) in order to explore various forms of discretion taken by SLBs in dealing with cases that the same, why is the form of discretion taken, and the impact on professionalism and quality of public services. Data collection techniques are: (1) observations relating to objects that can look like the behavior of SLBs in providing services; (2) in-depth interviews to explore forms of discretion and why discretion was taken by SLBs and their impact on professionalism and quality of public services; (3) documentary techniques to complete data from interviews and http://www.iaeme.com/IJCIET/index.asp 2227 editor@iaeme.com Discretion of Street-Level Bureaucrats in Public Services: A Case Study On Public Health In Makassar observations, the researcher will also collect a number of data and information from available documents related to health services in Makassar City. Data management and analysis techniques are using the Nvivo 12 Plus application developed by Tom Richard since 1981 (Gibss, 2004). The purpose and use of the NVivo 12 Plus application is so that data processing can be more efficient and effective so that the results can be accounted for. The stages in data management begins with importing research data into the NVivo 12 Plus application. The next stage is coding (open coding, axial coding, and analytical / selective coding). Open coding is done by making nodes in accordance with the research theme to be answered, namely the forms of discretion used by SLBs, the reason for discretion, and the impact on the people served. Axial coding is done by retrieving information from internal data files and then inserting them into themes or sub-themes that match the nodes. The last process carried out was to do selective coding by identifying and describing the forms of discretion used by the head of the PHC, doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and counters in health services, the reasons for using the discretion, as well as the impact on patients and also for the professionalism of SLB. 3. RESULTS SLBs in carrying out their duties to serve patients in PHC are often faced with limited resources. Therefore, the opportunity for discretion is very open to them. This study has interviewed 24 informants who are included in the SLBs, namely the Head of Puskesmas, Doctors, Nurses, Pharmacists, Midwives, and Counters, to explore the forms of discretion used by them when faced with various dilemmas in service. The questions we use to uncover the discretion used by the Head of the PHC regarding their main tasks are what problems you often face in carrying out your duties as head of the PHC, whether in overcoming these problems you use discretion, what constitutes their actions, and how is the legality of the decisions taken and the impact on the community as users of health services. The author will give specific examples of each answer to the questions we ask the informants. This is intended to provide a clearer picture of the decisions they take in carrying out their duties. 3.1. Discretion in Public Health Services The implementation of health services at the PHC is carried out by SLBs consisting of the Head of the PHC, Doctors, nurses, pharmacists, window clerks, and laboratory staff. The head of the PHC as the highest leader in the PHC has the main task of leading, supervising, and coordinating health services in a comprehensive manner to the community in their working area. In carrying out these basic tasks, a head of the PHC often takes discretion to get around the shortcomings and scarcity of resources. Each PHC has standard operating procedures, so that a head of the PHC in carrying out its duties always refers to the standard operating procedures. Based on the results of interviews with the heads of PHC, it can be concluded that the activities of monitoring and coordinating activities to doctors, nurses, pharmacists and clerk clocks can run in accordance with existing service standards. But there are some things that in certain conditions are forced by a Head of PHC to use discretion especially when getting pressure from the community of service users and to provide faster services. Carrying out my daily tasks, I often take discretion in overcoming various obstacles that I face. Such as providing referrals to patients who are forced to be referred by giving diagnosed disease information that is allowed to be referred. I was forced to lie by writing not in http://www.iaeme.com/IJCIET/index.asp 2228 editor@iaeme.com Hasniati Hamzah, Fitriani, Vinsenco R. Serano, Albertus, Y. Maturan and Muhammad Yunus accordance with the patient's condition, because if I was honest the hospital would not accept the patient. (SLBs1, PHC 1) When it comes to discretionary policies, I have held discretion several times to provide referral letters to patients who can still be treated or treated at the health center because the illness can still be treated. However, because of the pressure from the patients concerned, we were forced to provide referrals (SLBs 2, PHC 2) There are also SLBs who refer patients to the hospital because of the limited equipment they have, the following excerpts of the interview: Some occasions I took a policy to refer patients because the limitations of the existing equipment in the PHC were not adequate, although in the rules Health Care Security (BPJS) was not allowed to be referred to the hospital because for such diseases it should be the authority of the PHC to serve it (SLBs 3, PHC 3) The discretion taken by doctors is generally related to drug administration. For medicines available at the PHC, doctors often give prescriptions to be purchased at the pharmacy. Whereas in the rules, the patient has the right to get medicine at the PHC according to the illness he suffers, but because the doctor wants the patient to take a better quality medicine, the doctor prescribes it to be purchased at the pharmacy. On the one hand, a pharmacy officer can replace drugs prescribed by a doctor, with similar drugs as long as they have the same properties as drugs written by doctors. Discretion is carried out on the provision of drugs that are sometimes not available at the PHC given prescriptions, so they do not replace drugs. Unless anti-biotic drugs are usually replaced with other brands with the same composition (SLBs 4, PHC 1) Another form of discretion that is mostly carried out by SLBs in PHC is to serve patients even though the domicile of the patient is not included in the coverage that can be served according to the provisions of Health Care Security (BPJS) regulations. In the Regulation Number 1 of 2017 concerning Equity of Participants in First Level Health Facilities, patients who can be served are those who have a domicile in accordance with the coverage area of the PHC. Take a policy to continue to provide services to patients who are not included in the service area in accordance with BPJS rules with consideration for patient policies and safety (SLBs 23, PHC 3) In general, there are two discretions that are often taken by the window clerk, namely (1) issuing a policy not to go to the counter for patients who need immediate treatment or action such as accident victims, and not queuing for the elderly and disabled, (2) registration services online patients have not been run because they are considered to be rambling. Although online patient services have been suggested by the Department of Health with consideration of the high patient visits. Both types of discretion are basically aimed at the effectiveness and efficiency of services provided to patients, and primarily aim to provide fast services for patients who immediately need services. 3.2. Professionalism of SLBs in Using Discretion Professionalism in using discretion becomes very important in health services. This is because of the impact of discretion which can be fatal for patients. A doctor, nurse, or pharmacist must prioritize patient safety in providing health services, even if the patient urges to get certain medicines to cure the illness. Not infrequently in health services occurs a patient asks the doctor to write a prescription according to his wishes, even though in terms of medical medicine is very dangerous. http://www.iaeme.com/IJCIET/index.asp 2229 editor@iaeme.com Discretion of Street-Level Bureaucrats in Public Services: A Case Study On Public Health In Makassar I often handle patients who insist on sleeping pills every time they come for treatment, even though the use of sleeping pills for a long time will have a negative impact on the patient's health because it will cause dependence. In cases like this, I only provide vitamins (SLBs 6, PHC 3) A number of informants interviewed stated that in using discretion, which is the top priority is to provide good service to patients, and pay attention to patient recovery. Like the example of a nurse who handles a patient's ulcer wound. Sometimes it does not follow SOPs or theories such as treating ulcers / abscesses based on existing experience and using cold heat treatment using hair drayer and ice cubes, depending on the wound. So even though doctors recommend taking drugs such as supratur, because they contain high vaseline so that ulcers that have ulcers can get worse (according to experience), sometimes only using Rifanol, and sometimes not using gauze to treat the patient's wounds, due to injury considerations very severe patients (SLBs 12, PHC 1) In certain cases it was also found that a nurse dared to advise the doctor not to give referrals to patients because they felt that the patient could still be treated at the PHC. In another case example, a midwife at the PHC 4 showed her professionalism in handling a mother who would give birth. Even though the medical equipment and facilities are classified as modest, but he is able to help deliver well and satisfy the patient. In the condition of the patient who had to give birth, I tried to help her delivery. At that time, the doctor was not in place, but because of the emergency patient's condition, I tried to provide first aid according to my abilities, such as giving an IV, then I consulted the doctor by telephone, because doctors were not always in the PHC (SLBs 16 , PHC 4). I replace the tools used to treat patients with other devices that are considered to have the same function as patient safety considerations. For example, replace gauze with gloves to cover bleeding temporarily. This action was taken because it was considered not to endanger the patient (SLBs 23, PHC 3). From the two examples above, it appears that SLBs take professional discretion based on their experience in handling patients. In addition, the experience of the two SLBs in taking discretion reflects that each SLBs have the authority to take discretion, as long as SLBs are confident in their abilities. Faith and sincere intentions to help others will help them deal with every problem faced. 3.3. Consideration in Using Discretion A number of SLBs interviewed revealed that the main consideration in using discretion was to provide a more responsive and fast service, in order to save the lives of patients being served. The provision of referrals that should not be given by the Head of the PHC to urgent patients, neglect of the queuing system to patients in an emergency condition, the provision of services to patients who are not service areas, is an example of the desire of SLBs to provide fast and satisfying services to patients. Even though in reality, the Head of the PHC must write a diagnosis that is not in accordance with the patient's condition, but because he wants to show empathy to the patient. 3.4. Impact of Discretion The discretion carried out by the head of the PHC, doctors, nurses, pharmacists, booth clerk as a whole aims to provide fast and satisfying service to the community. This can be seen from the discretion used by paramedics to provide services that are needed by the community. Among them is to provide convenience for access to advanced health services. The head of the http://www.iaeme.com/IJCIET/index.asp 2230 editor@iaeme.com Hasniati Hamzah, Fitriani, Vinsenco R. Serano, Albertus, Y. Maturan and Muhammad Yunus PHC makes referrals to the community when it is really needed by the community to get better quality health services such as better medical equipment that the PHC cannot provide. Thus, the general discretion used by SLBs in PHC has a positive impact on the community (patients). These positive impacts can be identified as follows: (1) ease of access to services, as perceived by people who are not domiciled outside the working area of the PHC, (2) the speed of obtaining services, as perceived by patients who do not need to queue for service due to conditions which requires prompt handling, (3) improvement of service facilities, as perceived by the community requesting referrals to hospitals because of limited facilities owned by the PHC, (4) increasing satisfaction of the people served. 4. DISCUSSION It was found that, in connection with the implementation of the BPJS Regulation No. 1 of 2017 concerning Equity of Participants in First-Level Health Facilities, the PHC had the authority to interpret the rules they considered appropriate. The head of the PHC as a line level manager at the first level health service, generally takes positive discretion regarding health services, namely providing health services to patients who are not actually in the service area, for example someone from another district in South Sulawesi, what happened to Makassar visited relatives and suddenly experienced pain. because of the condition of the patient who needs quick help, even though in terms of the patient's rules cannot be served, the Head of the PHC instructs the doctor to serve the person concerned. In the case as above, discretion for SLBs is important to do considering its link to efforts to improve the effectiveness of public services. Therefore SLBs must be given a more loose discretionary space as long as they are intended for good for the people being served (Wibawa, 2009). With a more loose discretionary space, SLBs can carry out their duties and functions independently and professionally (Cheraghi-Sohi & Calnan, 2013; Evans, 2011), especially in public services where they are dealing directly with people with a high level of plurality. Another finding in this study is that line level managers (PHC heads) have flexibility in taking discretion, such as taking the wisdom to provide a referral letter for actual hospital admission that these patients can still be treated at PHC. This finding is in line with Wangrow, et all (2015) that at the manager level there is flexibility for discretion or the latitude of action available to managers (Evans, 2011). The way to get around the rules is to provide a diagnosis of the disease that can be referred to. This referral letter is due to pressure from patients who want to get services with more complete facilities at the hospital. In the regulations, a patient who can be referred to a hospital is if the disease suffered by the patient cannot be treated at the PHC. But because of the demand and pressure from patients who do not want to understand the regulation, the Head of the PHC is forced to provide a reference. This finding is interesting, because discretion is usually done because of pressure from above (top-down (Loveland, 1991) or because of limited resources (Lipsky 2010, Alden, 2015), but in this health service at PHC, discretion is taken not only solely because of the limited resources available, but also because of the pressure (bottom-up) that comes from patients who want to get better service. In other cases, often the Head of the PHC takes discretion to refer patients to the hospital because of the limited resources they have, such as the limitations of medical equipment owned. This is in line with Lipsky's (1980) view that uneven distribution of resources results in uneven, which forces SLBs to take a policy of insurance for their shortcomings. Coping behavior carried out by SLBs has also been written by Lipsky (1980) approximately forty years ago. The behavior of the prevention carried out by the Head of the PHC is to write a diagnosis according to the illness that can be referred to, in order to provide an opportunity for patients to get more adequate health services, especially in terms of equipment. http://www.iaeme.com/IJCIET/index.asp 2231 editor@iaeme.com Discretion of Street-Level Bureaucrats in Public Services: A Case Study On Public Health In Makassar From the cases of discretion taken by SLBs in the PHC, it shows that the discretion taken is all aimed at the safety and interests of the patient. The assumption that develops, discretion is dangerous so it must be limited or not even necessary. But Wibawa (2009) argues differently, that SLBs need to be given more discretionary space along with paying for their performance, which can increase public service efforts without increasing corruption (Kwon, 2014). Wibawa (2009) further argued that bureaucratic discretion would need to be protected so that anyone who would use the bureaucracy for their own interests or the group would get strict sanctions. Bureaucratic officials in carrying out their duties and responsibilities need to be protected when taking discretionary decisions in order to overcome more urgent problems. The line of authority between political and bureaucratic officials needs to be emphasized so that no one intervenes and dominates among them which in turn harms the public interest The sluggish bureaucracy that has always been complained about so far in public services, especially in administrative services, is rarely found in health services in PHC. It might be because the context of the service provided is different from the administrative service. Health care is more about humanitarian issues. SLBs who work in the PHC get a feeling of satisfaction (intrinsic satisfaction) when they can help patients who are served. Motivation of public services (Perry & Wise, 1996) from SLBs can be demonstrated by a commitment to the desire to serve the public interest (Downs, 1967). 5. CONCLUSION Discretion can be defined as the ability of SLBs to choose between alternatives and decide how a government policy must be implemented in certain situations. Discretion in public health is taken not only solely because of the limited resources available, but also because of the pressure (bottom-up) that comes from patients who want to get better service. The discretion taken by SLBs in health services shows that discretion are basically aimed at the effectiveness and efficiency of services provided to patients, and primarily aim to provide fast services for patients who immediately need services. The results showed that the level of discretionary use was different for each SLBs. Courage to take discretion is strongly influenced by the experience and independence of SLBs, as well as considering the impact on patients. In general, the discretion taken solely aims to facilitate service and is based on the desire to save the lives of patients served. REFERENCES [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] Alden, S. (2015). Discretion on the Frontline: The Street Level Bureaucrat in English Statutory Homelessness Services. Social Policy & Society. Vol. 14:1, page 63–77 Alexander Phuk Tjilen, Fitriani, Hesty Tambayong, Albertus Yosep Maturan, Samel Watina Ririhena and Fenty Y. Manuhutu, 2018. Participation in Empowering Women and the Potential of the Local Community Economy, a Case Study in Merauke Regency, Papua Province, International Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Technology, 9(12), pp. 167–176. Barth, T. J. (1992). The Public Interest and Administrative Discretion. The American Review of Public Administration. Vol. 22 No. 4 December 1, Pp. 289-300. Cann, S. (2007) "The Administrative State, the Exercise of Discretion, and the Constitution." Public Administration Review 67.4: 780-782. Cheraghi-Sohi, S. & Calnan, M., (2013). Discretion or Discretions. Delineating Professional Discretion: The Case of English Medical Practice. Social Science & Medicine. Vol. 96. Pp. 52-59. http://www.iaeme.com/IJCIET/index.asp 2232 editor@iaeme.com Hasniati Hamzah, Fitriani, Vinsenco R. Serano, Albertus, Y. Maturan and Muhammad Yunus [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21] [22] [23] [24] Dina Limbong Pamuttu, Herbin F Betaubun and Ashari Jalil, 2018. Testing of Peat Soil Compressive Strength Using Mixed Materials of Calcium and Cement, International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology, 9(10), pp. 883–886. Downs, A. (1967). Inside Bureaucracy. Boston: Little, Borwn. Elisabeth Lia Riani Kore, Funnisia Lamalewa, Ari Mulyaningsih. 2018. The Influence of Promotion, Trust, and Convenience to Online Purchase Decisions, International Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Technology 9(10), pp. 77–83. Evans, T. (2011). Professionals, Managers and Discretion: Critiquing Street-level Bureaucracy. British Journal of Social Work. Vol. 41(2), Pp. 368-386 Gibbs, G. (2004). Qualitative Data Analysis: Explorations with NVivo.Understanding Social Research, 257. Kwon, I. (2014). Motivation, Discretion, and Corruption, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. Vol. 24, Issue 3, 1 July 2014, pages 765-794. Lipsky, M. (2010). Street-Level Bureaucracy, 30th Ann. Ed.: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Service. Classics of Public Administration. Russell Sage Foundation, New. York. Loveland, I. (1991). Administrative Processes, and the Housing of Homeless Persons: A View from the Sharpend, Journal of Social Welfare Law, 13, 1, 4–26. Mangkoedihardjo, S. (2014). Three Platforms for Sustainable Environmental Sanitation. Current World Environment, 9(2): 260-263. Ortega. J. (2009). Employee discretion and performance pay. The Accounting Review. Vol. 84 No. 2. Pp. 589-612. DOI: 10.2308/accr.2009.84.2.589 Perry, J. L. & Wise, L. R. (1990). The Motivational Bases of Public Service. Public Administration Review. Vol. 50. No. 3 (May-June), pp. 367-373. Philipus Betaubun and Nasra Pratama Putra, 2019. Budget Planning Information System for Simple Housing in Merauke District,International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology, 10(2), pp. 783-792. Rabin, J. (2003). Administrative Discretion. Encyclopedia of Public Administration and Public Policy. New York: Dekker. p.35. Scott, P.G. (1997). Assesing Determinants of Bureaucratic Discretion: An Experiment in Street-level Decision Making. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, January, 7: 35-57. Sowa & Selden, J. (2003).Administrative Discretion and Active Representation: An Expansion of the Theory of Representative Bureaucracy. Public Administration Review. p. 700. Supriyadi, Richard S. Waremra and Philipus Betaubun, 2019. Papua Contextual Science Curriculum Contains with Indigenous Science (Ethnopedagogy Study at Malind Tribe Merauke), International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology, 10(02), pp. 1994– 2000 Tummers, L., & Bekkers, V. (2014). Policy Implementation, Street-level Bureaucracy, and the Importance of Discretion. Public Management Review. Vol. 16(4) 527-547 Vaishnav, S. & Marwaha, K. (2015). Judiciary: A Ladder between Inevitable Administrative Discretion and Good Governance. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Approach & Studies, 2(2), 63-72. Wangrow, D. Schepker, D. and Barker V.L. (2015). Managerial Discretion: An Empirical Review and Focus on Future Research Directions. Journal of Management. Vol. 41(1) 99-135 [25] Wibawa, S. (Editor). (2009). Public Administration: Contemporary Issues, Graha Ilmu, and Yogyakarta. http://www.iaeme.com/IJCIET/index.asp 2233 editor@iaeme.com