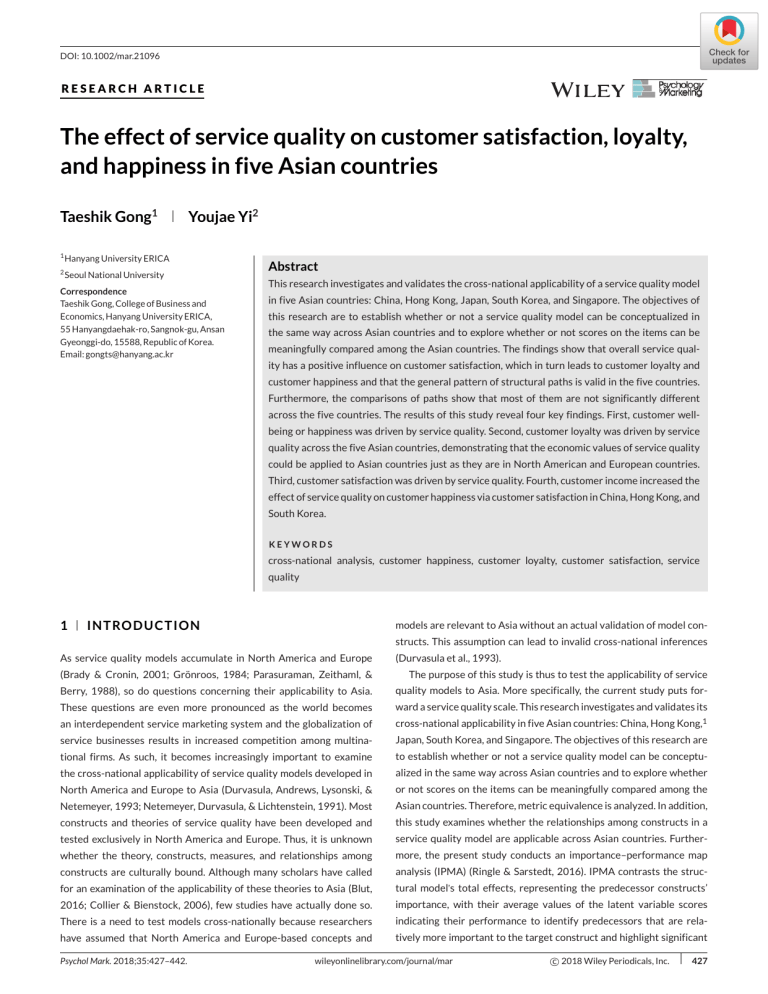

DOI: 10.1002/mar.21096 RESEARCH ARTICLE The effect of service quality on customer satisfaction, loyalty, and happiness in five Asian countries Taeshik Gong1 Youjae Yi2 1 Hanyang University ERICA 2 Seoul National University Correspondence Taeshik Gong, College of Business and Economics, Hanyang University ERICA, 55 Hanyangdaehak-ro, Sangnok-gu, Ansan Gyeonggi-do, 15588, Republic of Korea. Email: gongts@hanyang.ac.kr Abstract This research investigates and validates the cross-national applicability of a service quality model in five Asian countries: China, Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, and Singapore. The objectives of this research are to establish whether or not a service quality model can be conceptualized in the same way across Asian countries and to explore whether or not scores on the items can be meaningfully compared among the Asian countries. The findings show that overall service quality has a positive influence on customer satisfaction, which in turn leads to customer loyalty and customer happiness and that the general pattern of structural paths is valid in the five countries. Furthermore, the comparisons of paths show that most of them are not significantly different across the five countries. The results of this study reveal four key findings. First, customer wellbeing or happiness was driven by service quality. Second, customer loyalty was driven by service quality across the five Asian countries, demonstrating that the economic values of service quality could be applied to Asian countries just as they are in North American and European countries. Third, customer satisfaction was driven by service quality. Fourth, customer income increased the effect of service quality on customer happiness via customer satisfaction in China, Hong Kong, and South Korea. KEYWORDS cross-national analysis, customer happiness, customer loyalty, customer satisfaction, service quality 1 INTRODUCTION models are relevant to Asia without an actual validation of model constructs. This assumption can lead to invalid cross-national inferences As service quality models accumulate in North America and Europe (Durvasula et al., 1993). (Brady & Cronin, 2001; Grönroos, 1984; Parasuraman, Zeithaml, & The purpose of this study is thus to test the applicability of service Berry, 1988), so do questions concerning their applicability to Asia. quality models to Asia. More specifically, the current study puts for- These questions are even more pronounced as the world becomes ward a service quality scale. This research investigates and validates its an interdependent service marketing system and the globalization of cross-national applicability in five Asian countries: China, Hong Kong,1 service businesses results in increased competition among multina- Japan, South Korea, and Singapore. The objectives of this research are tional firms. As such, it becomes increasingly important to examine to establish whether or not a service quality model can be conceptu- the cross-national applicability of service quality models developed in alized in the same way across Asian countries and to explore whether North America and Europe to Asia (Durvasula, Andrews, Lysonski, & or not scores on the items can be meaningfully compared among the Netemeyer, 1993; Netemeyer, Durvasula, & Lichtenstein, 1991). Most Asian countries. Therefore, metric equivalence is analyzed. In addition, constructs and theories of service quality have been developed and this study examines whether the relationships among constructs in a tested exclusively in North America and Europe. Thus, it is unknown service quality model are applicable across Asian countries. Further- whether the theory, constructs, measures, and relationships among more, the present study conducts an importance–performance map constructs are culturally bound. Although many scholars have called analysis (IPMA) (Ringle & Sarstedt, 2016). IPMA contrasts the struc- for an examination of the applicability of these theories to Asia (Blut, tural model's total effects, representing the predecessor constructs’ 2016; Collier & Bienstock, 2006), few studies have actually done so. importance, with their average values of the latent variable scores There is a need to test models cross-nationally because researchers indicating their performance to identify predecessors that are rela- have assumed that North America and Europe-based concepts and tively more important to the target construct and highlight significant Psychol Mark. 2018;35:427–442. wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/mar c 2018 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. 427 428 GONG AND YI areas for improving management activities (Ringle & Sarstedt, 2016; SERVPERF scale is efficient compared to the SERVQUAL scale. Fur- Schloderer, Sarstedt, & Ringle, 2014). These findings, therefore, pro- ther, they show that the analysis of the structural models supports vide managers with specific information about measures they need to the theoretical superiority of the SERVPERF scale. Expanding beyond take to increase customer happiness (Hock, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2010). the question of “Is SERVPERF superior to SERVQUAL?” Park and Yi In addition, while much of the extant research on service quality has (2016) ask the question: “When is SERVPERF superior to SERVQUAL?” focused on enhancing customer loyalty, little research has focused on By comparing the two approaches from an analytic perspective, increasing social performance such as customer happiness and well- Park and Yi (2016) show that SERVPERF is superior to SERVQUAL being. That said, lately there has been a substantially increased inter- when the effect of performance on customer satisfaction is greater est in examining the relationship between service quality and customer than the effects of expectation on performance and customer satis- well-being. Interestingly, recent research has called for more focus on faction or when customers are heterogeneous in the evaluation of improving customer well-being through transformative service. This expectation. topic was one of 12 service research priorities (Ostrom et al., 2015). Third, Brady and Cronin (2001) adopt Rust and Oliver (1994) view Therefore, the present research examines how service quality affects that customers evaluate service quality based on three dimensions: (1) customer happiness. This study also tests the moderating role of cus- the customer–employee interaction, (2) the physical environment, and tomer income in the relationship between overall service quality and (3) the outcome. In addition, they adopt Dabholkar (1996) view that customer happiness through customer satisfaction. The article opens service quality has a hierarchical factor structure. More specifically, by reviewing the literature on the conceptualization and measurement Dabholkar (1996) proposes that customers think of service quality at of service quality models. The research methodology is explained, fol- different levels, such as the dimension level and the overall level. They lowed by an analysis of empirical research. Finally, the findings are dis- argue that service quality dimensions are distinct but highly correlated. cussed and the managerial implications are drawn. Thus, they conclude that service quality dimensions share an underlying theme and that a common higher-order factor is present, which is called overall service quality. In their effort to synthesize these concep- 2 THEORY AND HYPOTHESES 2.1 Service quality model tualizations, Brady and Cronin (2001) propose the hierarchical service quality model. Here, service quality is viewed as a hierarchical factor structure. That is, there is a common higher order factor called overall service quality, and it consists of three dimensions: performance qual- In the service marketing literature, there has been considerable ity, delivery quality, and physical environment quality. Since this is the progress in discussing how service quality should be measured. First, first measure synthesizing all major prior conceptualizations, it is the Grönroos (1984) argues that service quality consists of two dimen- most fruitful approach to service quality assessment to date (Dagger, sions: technical quality and functional quality. Technical quality refers Sweeney, & Johnson, 2007; Pollack, 2009; Yi & Gong, 2008). to what customers receive as a result of their interactions with a ser- According to Grönroos (1984), the performance (outcome) quality vice firm. This aspect can be called the outcome quality dimension. On dimension refers to the result of the service transaction. It is con- the other hand, functional quality represents how the service is deliv- cerned with what the customer actually receives from the service ered. In other words, the way service employees interact with cus- transaction. Prior studies show that performance quality is a signifi- tomers has an impact on customers’ view of the service. This aspect is cant determinant of overall service quality and the addition of outcome called the interaction quality dimension. quality significantly improves the explanatory power and predictive Second, Parasuraman et al. (1988) propose five dimensions of ser- validity of the service quality model (Powpaka, 1996). Furthermore, vice quality. More specifically, (1) tangibles are appearances of physical Bolton and Drew (1991) assert that service performance levels are elements, (2) reliability is dependable and accurate performance, (3) inputs to customers’ perceptions of overall service quality. In addition, responsiveness is promptness and helpfulness, (4) assurance is cred- Brady and Cronin (2001) argue that there is a consensus that the per- ibility, security, competence, and courtesy, and (5) empathy is easy formance quality of a service encounter significantly affects customer access, good communication, and customer understanding. To measure perceptions of overall service quality. Thus, the following hypothesis is service quality, they develop a survey instrument called SERVQUAL, proposed: which is based on the premise that customers evaluate a firm's service quality by comparing their perceptions of its service with their own expectations (Sivakumar, Li, & Dong, 2014). That is, SERVQUAL H1: Perceptions of the quality of service performance directly contribute to overall service quality perceptions. measures the service quality as the gap between expectation and per- Service delivery quality focuses on customers’ perception of the formance. Meanwhile, Cronin and Taylor (1992) point out that lit- employee–customer interactions that take place during service deliv- tle theoretical and empirical evidence supports the relevance of the ery (Grönroos, 1984). Interpersonal interactions have an influence expectations–performance gap as the basis for measuring service qual- on customer perceptions of overall service quality because of the ity. Instead, they argue the superiority of simple performance-based intangibility and inseparability of services (Brady & Cronin, 2001). measures of service quality (Babakus & Boller, 1992; Park & Yi, 2016). More specifically, customers evaluate overall service quality based on Accordingly, they develop the performance-only measure (SERPERF) their perception of employees’ responsiveness, empathy, reliability, as an alternative to the SERVQUAL measure. They conclude that the and professionalism (Ekinci & Dawes, 2009). Choi and Kim (2013) also 429 GONG AND YI suggest that interpersonal interactions have a critical impact on cus- H4: esis is proposed: H2: Overall service quality is positively related to customer satisfaction. tomer perception of overall service quality. Thus, the following hypothH5: Customer satisfaction is positively related to customer loyalty. Perceptions of the quality of service delivery directly contribute to overall service quality perceptions. 2.3 Customer happiness Brady and Cronin (2001) report that services require the cus- Service has been firmly established as a critical means for enhancing tomer to be present during the process and that the surrounding firm performance. Furthermore, service now dominates the lives of physical environment can serve as an important basis for customers’ consumers and therefore marketers have the opportunity to improve evaluations of the overall quality of the service encounter. Baker, consumer happiness and begin to concentrate on enhancing customer- Parasuraman, Grewal, and Voss (2002) show that the physical store related outcomes as well (Anderson et al., 2013; De Keyser & Lariviere, environment can affect customer service quality evaluations. Bitner 2014). The primary focus of service marketing has thus shifted from (1992) argues that the physical environment, such as the type of office satisfying customer needs to enhancing customer happiness. In furniture and the décor, may influence a client's beliefs about a lawyer's other words, the purpose of service marketing has been broadened performance or overall service evaluations because the perceived and centered on the improvement of customer happiness beyond servicescape elicits cognitive responses. In-store cleanliness is asso- customer satisfaction (Sirgy, Samli, & Meadow, 1982). This emerging ciated with the service quality of a shopping environment. Customers area has been referred to as transformative service research, which utilize environmental cues to make inferences about the quality of is defined as any research that investigates the relationship between products/services (Chao, 2008). Thus, the following hypothesis is service and customer happiness aiming at improving the lives of proposed: customers (Anderson & Ostrom, 2015). In a similar manner, a social H3: Perceptions of the quality of the service environment directly contribute to overall service quality perceptions. marketing perspective emphasizes that marketing should deliver value to customers in a way that improves customers’ happiness. Therefore, under the social marketing concept, firm performance is measured by social outcomes such as customer happiness (Su, Swanson, & 2.2 Service quality and its consequences Researchers see service quality as having an important influence Chen, 2016). Furthermore, the social marketing concept assesses the societal impact of service marketing on customer happiness (Dagger & Sweeney, 2006). on customer satisfaction, customer loyalty, and customer happiness. Customer happiness is conceptualized as customers’ perception of According to Lazarus's theory of emotion and adaptation (Lazarus, the extent to which their well-being and quality of life are enhanced. 1991), the appraisal processes of situational conditions lead to emo- Thus, customer happiness reflects the culmination of customers’ tional responses, which in turn induce coping activities: appraisal → subjective evaluation of their current life circumstances (Dagger & emotional response → coping (Bagozzi, 1992). Adapting this theory to Sweeney, 2006; De Keyser & Lariviere, 2014; Hellén & Sääksjärvi, a service context, it is likely that the overall service quality appraisal 2011). Dagger and Sweeney (2006) point out that a series of ser- precedes emotional responses such as customer satisfaction. Further, vice encounters results in perceptions that form the basis of cus- in the presence of a particular emotion, coping responses such as intent tomers’ satisfaction evaluation, which in turn leads to customer reac- to maintain and enjoy the outcome are possible (e.g., customer loyalty tions such as customer happiness. In addition, Sweeney, Danaher, and and customer happiness) (Cronin, Brady, & Hult, 2000). The service McColl-Kennedy (2015) suggest that customer satisfaction with con- literature reports empirical results suggesting that customer satisfac- crete events spills over to life domains, which in turn leads to cus- tion is an intervening variable that mediates the relationship between tomer happiness. In a similar logic, the bottom-up theory of customer overall service quality perception and customer loyalty (Taylor & Baker, happiness states that customer satisfaction with the specific service 1994). In addition, Szymanski and Henard (2001) conduct a meta- encounter spills over upward to the overall service satisfaction, which analysis and document that performance (e.g., overall service quality) in turn spills over upward to the most superordinate domain of cus- positively affects customer satisfaction and that the outcome of cus- tomer life satisfaction such as customer happiness (Neal, Uysal, & Sirgy, tomer satisfaction is customer loyalty (e.g., word-of-mouth and repur- 2007). chase intentions). Furthermore, Hellier, Geursen, Carr, and Rickard Although the extensive body of research on customer loyalty has (2003) find that overall service quality influences customer satisfac- focused primarily on benefits to the firm, customer loyalty can also tion, which in turn leads to customer loyalty. Early research identifies result in benefits to the customer in the form of customer happiness customer satisfaction as the main predictor of customer loyalty (Hume (Aksoy et al., 2015). According to Aksoy et al. (2015), the primary & Mort, 2010; Patterson, Johnson, & Spreng, 1997; Sweeney, Soutar, & role of customer loyalty is to make customers happy because the core Johnson, 1999). principle of customer loyalty is to connect friends and family, which All in all, it is expected that overall service quality is an antecedent are the primary determinants of customer happiness (Nicolao, Irwin, of customer satisfaction and that satisfied customers are more likely & Goodman, 2009). Gilbert (2005) asserts that friends and families to engage in positive word-of-mouth and repurchase (Pollack, 2009). offer strong social connections, interactions, and a sense of security, Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed: all contributing to customer happiness. Furthermore, customer loyalty 430 GONG AND YI Performance service quality Delivery service quality Customer loyalty H1 H2 H5 Overall service quality H4 Customer satisfaction H3 H7 H6 Customer happiness Environment service quality FIGURE 1 Conceptual framework is driven by the interactions that customers develop with employees, The demographics of the sample are presented in Table 1 The sam- which in turn lead to customer happiness. All individuals have needs ple consists of 175 (China), 178 (Hong Kong), 172 (Japan), 180 (South for belonging and interdependence, and these needs can be fulfilled Korea), and 174 (Singapore) valid responses. The unit of analysis of through customer loyalty, which can be defined as a desire to maintain this study is an individual shopper who had made three purchases the relationship (Aksoy et al., 2015). In addition, customers develop within three months at a major department store at the time of data affectionate bonds with services, which in turn lead to customer loy- collection. Self-administered questionnaires were used as the method alty, which is argued to be a catalyst for customer happiness (Yim, Tse, of data collection. The potential respondents were approached when & Chan, 2008). This view is also supported by Orth, Limon, and Rose they were leaving department stores and asked to participate in a short (2010) who find that customer loyalty toward the service arouses cus- survey by a study assistant. They were informed about the investiga- tomer happiness. Furthermore, a customer's interaction with the ser- tion and told that the individual responses were to be kept strictly con- vice employee may arouse positive emotions, which in turn lead to fidential. A study assistant waited while participants completed the customer loyalty. Interestingly, rewarding experiences with services research questionnaires. through customer loyalty make the customer feel better. Finally, hap- As the survey was conducted in five countries, five versions of the piness results from customers’ repeated experience with services, that questionnaire were administered. The questionnaire, originally writ- is, customer loyalty (Bettingen & Luedicke, 2009). Thus, the following ten in English, was translated into Mandarin Chinese, Cantonese Chi- hypotheses are proposed: nese, Japanese, and Korean by bilingual people whose native language H6: Customer satisfaction is positively related to customer happiness. H7: Customer loyalty is positively related to customer happiness. Figure 1 provides a conceptual model of service quality and illustrates the hypothesized relationships among the key constructs. was Mandarin Chinese, Cantonese Chinese, Japanese, or Korean, respectively. These translated questionnaires were then translated back into English by another bilingual person whose native language was Mandarin Chinese, Cantonese Chinese, Japanese, or Korean, respectively. These two English versions were then compared and no item was found to contain a specific cultural context in terms of language (Brislin, 1980). The questionnaire was pretested with 20 shoppers at the department store, and there were no major problems with understanding or wording. 3 METHOD 3.2 3.1 Sample and procedures Instrumentation The research derived measures for key constructs from existing scales Data were collected through a survey that was distributed to con- in the literature. All constructs were measured with items using 9-point sumers in each of the five countries: China, Hong Kong, Japan, South Likert scales ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 9 = strongly agree. Korea, and Singapore. Quota sampling was used to generate samples Measurement scales for all constructs are summarized in Table 2. Ser- that were representative of the population in terms of age and gender. vice quality questions were from Dabholkar, Thorpe, and Rentz (1996) China, Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, and Singapore served as the as well as Brady and Cronin (2001). More specifically, performance ser- countries of study because they share similar cultural values and norms vice quality was measured by six items that assessed the availability, (Hofstede, Hofstede, & Minkov, 2010). Finding differences between quality, differentiation of merchandise, the extent to which service was countries with similar cultural backgrounds allows us to make a more customer-oriented, and the extent to which new products were pro- convincing argument than conducting the same study across countries vided compared to others. Delivery service quality was measured by that differ greatly in cultural background. Moreover, using countries six items that assessed the extent to which employees gave prompt, with highly disparate cultural backgrounds could introduce significant courteous, individual, voluntary, and knowledgeable service to cus- biases into our samples, which could limit the possibility of generalizing tomers. In addition, these items assessed the extent to which employ- the findings. ees were able to handle customer complaints directly and immediately 431 GONG AND YI TA B L E 1 Demographic profile of respondents Percent China Gender Age Education level Hong Kong Japan South Korea Singapore Male 25.71 25.84 26.16 26.10 25.86 Female 74.29 74.16 73.84 73.90 74.14 20–29 18.28 17.98 18.02 18.30 18.39 30–39 31.43 31.46 31.98 31.70 31.61 40–49 31.43 31.46 31.98 31.70 31.61 50–59 18.86 19.10 18.02 18.30 18.39 Secondary 10.28 41.01 18.02 27.80 38.51 Bachelor 74.86 48.88 73.26 63.80 50.00 Master/Ph.D. 14.86 10.11 8.72 8.70 11.49 on the site. Environment service quality was measured by six items that Henseler, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2015; Voorhees, Brady, Calantone, & assessed the extent to which the department store had a professional, Ramirez, 2016). The composite reliabilities for all variables exceed the modern-looking, and convenient appearance. In addition, these items cutoff value of 0.70, and the AVE for all focal variables exceeds the 0.50 assessed the extent to which customers perceived a positive physical benchmark, demonstrating that each construct has acceptable psycho- environment, parking places that were large and convenient, and a lay- metric properties. In support of the convergent validity of the scales, out that made it easy to find products. all indicators load significantly (p < 0.05) and substantially (>0.70) on Overall service quality and customer satisfaction were measured their hypothesized factors (see Table 2). Furthermore, all HTMT val- using a one-item scale because these constructs are easily understood ues are lower than the threshold value of 0.85. In addition, neither of and imagined (e.g., overall service quality, overall customer satisfac- the 95% bias-corrected and accelerated confidence intervals (CIs) of tion) (Bergkvist & Rossiter, 2007; Rossiter, 2002). Customer loyalty the HTMT ratio of correlations statistic includes the value 1.00 (see was measured by a two-item scale. These items were “I will say posi- Table 3), thus supporting discriminant validity. tive things about XYZ to other people” and “I intend to continue doing This study relies on one source of data, that is, ratings by customers, business with XYZ” (Zeithaml, Berry, & Parasuraman, 1996). Finally, so potential common method bias is statistically controlled (MacKen- customer happiness was measured by two items, “My quality of life is zie, Podsakoff, & Jarvis, 2005). First, following the procedure suggested enhanced by doing business with XYZ” and “I think XYZ contributes by Williams and Anderson (1994), a method factor was added with to customers’ happiness” (Dagger & Sweeney, 2006; Sweeney et al., all indicators for all latent variables loading on this factor. The struc- 2015). tural results are consistent with the original structural model for all five countries. This study also implemented the procedure used by Liang, Saraf, Hu, and Xue (2007). The results show that method factor load- 4 RESULTS ings are not significant and the ratio of substantive variance to method variance is more than 100:1 for all five countries, which means that The present study used the SmartPLS 3 software (Ringle, Wende, common method bias is not a serious issue. & Becker, 2015) to validate the measurement model and test the Henseler, Ringle, and Sarstedt (2016) advocate the test of mea- hypotheses. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS- surement invariance before performing a multigroup analysis between SEM) is a composite-based approach to structural equation modeling two or more groups when using SEM. They suggest the measurement (SEM) that forms composites as linear combinations of their respec- invariance of composites (MICOM) that is suitable for PLS-SEM. Given tive indicators, which in turn serve as proxies for the conceptual vari- that the current study aims to compare a model over two groups ables (Hair, Hult, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2017). Recent research argues via PLS-SEM, MICOM was adopted. MICOM is a three-step process that employing modeling constructs as composites is a more realistic involving (1) configural invariance assessment (i.e., equal parameteri- approach to measurement (Sarstedt, Hair, Ringle, Thiele, & Gudergan, zation and way of estimation), (2) compositional invariance assessment 2016). Furthermore, this study focuses on predicting customer satis- (i.e., equal indicator weights), and (3) assessment of equal means and faction, customer loyalty, and customer happiness via service quality, variances. If configural and compositional invariance are established, which calls for the use of PLS-SEM as a prediction-oriented approach partial measurement invariance is also established. If partial measure- to SEM (Hair, Hult, Ringle, Sarstedt, & Thiele, 2017). ment invariance is confirmed, one can compare the path coefficient Assessment of the measurement models includes composite reli- estimates across the groups. ability to evaluate the internal consistency and average variance Step 1 of the MICOM procedure, configural invariance, was estab- extracted (AVE) to evaluate the convergent validity. Assessment lished because the PLS path model setups are equal across the five of measurement models also involves discriminant validity. The countries, and group-specific model estimations draw on identical heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations can be used to algorithm settings. Next, to establish compositional invariance (step examine discriminant validity (Hair, Hult, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2017; 2), the original composite score correlation c was compared with the 0.87 0.90 0.88 0.70 0.70 2. XYZ offers high quality merchandise. 3. The service of XYZ is customer-oriented. 4. I achieve my purpose when I use the service of XYZ. 5. XYZ continuously provides new products compared to others. 6. XYZ provides differentiated services that others do not. 0.83 0.84 0.87 0.87 0.92 0.86 1. Employees of XYZ have the knowledge to answer customers’ questions. 2. Employees of XYZ are consistently courteous with customers. 3. XYZ gives customers individual attention. 4. The attitude of XYZ's employees demonstrates their willingness to help me. 5. Employees of XYZ give prompt services to customers. 6. Employees of XYZ are able to handle customer complaints directly and immediately. Delivery 0.86 1. XYZ has merchandise available when the customers want it. Performance Loadings China Measurement model Construct/indicator TA B L E 2 0.96 0.92 Reliability 0.70 0.67 AVE 0.90 0.93 0.93 0.94 0.92 0.89 0.75 0.78 0.88 0.87 0.87 0.88 Loadings Hong Kong 0.97 0.93 Reliability 0.84 0.67 AVE 0.89 0.91 0.83 0.89 0.90 0.88 0.78 0.70 0.86 0.87 0.88 0.83 Loadings Japan 0.96 0.92 Reliability 0.78 0.67 AVE 0.90 0.93 0.92 0.89 0.90 0.82 0.79 0.72 0.87 0.90 0.86 0.86 Loadings South Korea 0.96 0.93 Reliability 0.80 0.70 AVE Singapore 0.84 0.91 0.85 0.92 0.92 0.89 0.75 0.73 0.75 0.83 0.89 0.79 Loadings 0.96 0.91 Reliability (Continues) 0.79 0.63 AVE 432 GONG AND YI (Continued) 0.88 0.9 0.82 0.74 3. XYZ has modern-looking equipment and fixtures. 4. XYZ has clean, attractive, and convenient public areas (restrooms, fitting rooms). 5. XYZ provides plenty of convenient parking for customers. 6. The store layout of XYZ makes it easy for customers to find what they need. 0.95 2. I intend to continue doing business with XYZ. 0.94 0.94 1. My quality of life is enhanced by doing business with XYZ. 2. I think XYZ contributes to customers’ happiness. Customer happiness 0.95 1 1. I will say positive things about XYZ to other people. Customer loyalty 1. Overall, I am satisfied with XYZ. Customer satisfaction 1. I believe XYZ offers excellent service. 1 0.86 2. I would rate XYZ's physical environment highly. Overall service quality 0.86 Loadings China 1. Employees of XYZ have a neat, professional appearance. Environment Construct/indicator TA B L E 2 Reliability 0.96 0.94 1 1 0.93 AVE 0.92 0.89 1 1 0.70 0.96 0.96 0.95 0.94 1 1 0.81 0.88 0.87 0.88 0.88 0.89 Loadings Hong Kong Reliability 0.96 0.95 1 1 0.95 AVE 0.92 0.90 1 1 0.75 0.96 0.96 0.91 0.88 1 1 0.71 0.76 0.87 0.84 0.90 0.89 Loadings Japan Reliability 0.96 0.90 1 1 0.93 AVE 0.92 0.81 1 1 0.70 0.96 0.97 0.96 0.96 1 1 0.70 0.82 0.85 0.86 0.88 0.82 Loadings South Korea Reliability 0.96 0.96 1 1 0.92 AVE 0.93 0.92 1 1 0.67 0.96 0.97 0.96 0.96 1 1 0.75 0.79 0.90 0.88 0.90 0.89 Loadings Singapore Reliability 0.97 0.97 1 1 0.94 AVE 0.94 0.94 1 1 0.73 GONG AND YI 433 434 GONG AND YI TA B L E 3 Discriminant validity assessment results Variable Performance Delivery Environment Service quality Customer satisfaction Customer loyalty Customer happiness China [0.78, 0.92] Hong Kong [0.79, 0.91] Japan [0.84, 0.94] South Korea [0.68, 0.88] Delivery Singapore [0.73, 0.87] China [0.67, 0.89] Hong Kong [0.76, 0.88] [0.75, 0.87] Japan [0.57, 0.81] [0.56, 0.82] Environment Service quality Customer satisfaction Customer loyalty [0.71, 0.89] South Korea [0.56, 0.79] [0.55, 0.82] Singapore [0.69, 0.86] [0.79, 0.92] China [0.72, 0.93] [0.71, 0.88] [0.56, 0.83] Hong Kong [0.71, 0.85] [0.79, 0.89] [0.75, 0.86] Japan [0.71, 0.85] [0.70, 0.84] [0.69, 0.85] South Korea [0.74, 0.87] [0.74, 0.86] [0.58, 0.79] Singapore [0.63, 0.84] [0.66, 0.86] [0.68, 0.86] China [0.75, 0.92] [0.66, 0.84] [0.55, 0.80] [0.74, 0.91] Hong Kong [0.72, 0.85] [0.80, 0.89] [0.68, 0.83] [0.76, 0.84] Japan [0.71, 0.86] [0.71, 0.85] [0.66, 0.83] [0.79, 0.86] South Korea [0.70, 0.88] [0.76, 0.88] [0.55, 0.77] [0.71, 0.84] Singapore [0.58, 0.81] [0.61, 0.84] [0.52, 0.82] [0.75, 0.94] China [0.78, 0.95] [0.63, 0.84] [0.60, 0.85] [0.68, 0.86] [0.73, 0.87] Hong Kong [0.63, 0.82] [0.68, 0.84] [0.67, 0.82] [0.79, 0.89] [0.77, 0.89] Japan [0.77, 0.95] [0.72, 0.89] [0.76, 0.96] [0.72, 0.87] [0.69, 0.85] South Korea [0.62, 0.83] [0.66, 0.84] [0.59, 0.86] [0.66, 0.83] [0.69, 0.85] Singapore [0.46, 0.72] [0.56, 0.82] [0.60, 0.82] [0.70, 0.84] [0.64, 0.83] China [0.78, 0.97] [0.71, 0.92] [0.61, 0.88] [0.69, 0.87] [0.71, 0.86] [0.70, 0.87] Hong Kong [0.74, 0.88] [0.80, 0.91] [0.72, 0.86] [0.74, 0.86] [0.73, 0.85] [0.72, 0.87] Japan [0.73, 0.88] [0.65, 0.83] [0.75, 0.88] [0.63, 0.84] [0.62, 0.84] [0.73, 0.85] South Korea [0.57, 0.77] [0.68, 0.82] [0.57, 0.78] [0.65, 0.82] [0.63, 0.83] [0.71, 0.85] Singapore [0.59, 0.83] [0.55, 0.81] [0.61, 0.83] [0.71, 0.86] [0.69, 0.86] [0.75, 0.90] Notes: The numbers in brackets are the 95% bias-corrected and accelerated confidence intervals of the HTMT statistic. empirical distribution of the composite score correlation resulting invariance, the samples from five countries were compared by means from the permutation procedure (cu ) with 1000 permutations and a of multigroup analysis. In the first step, the omnibus test of group dif- 5% significance level for each combination of countries. If c exceeds the ferences was applied to assess if the path coefficients are equal across 5% quantile of cu , compositional invariance is established. The results the five groups. The analysis reveals that, in respect of all five structural in Table 4 show that partial measurement invariance is established model relations, the null hypothesis that the seven path coefficients among all five countries, thus allowing for a multigroup analysis that are equal across the five groups can be rejected. These results suggest compares the path coefficients among the samples from these five that, in respect of all relationships, at least one path coefficient differs countries to identify significant differences. However, this study did from the remaining four across the five countries (Sarstedt, Henseler, not assess the equality of the composite mean values and variances & Ringle, 2011). Next, Table 6 shows the differences in seven path (step 3) because the purpose of this study is to focus on cross-country coefficient estimates across five countries and provides the results of comparisons and not to pool the data. multigroup comparison. The analysis shows that path coefficient esti- R2 Table 5 lists the beta coefficients for five countries, along with the mates are partially invariant across the samples from five countries, as value for each endogenous construct. The models demonstrate only two path coefficient estimates are significantly different. good explanatory power, as the R2 values range from 0.53 to 0.87 Furthermore, this study uses an IPMA to extend the PLS-SEM (Henseler, Hubona, & Ray, 2016). The bootstrapping analyses using results by taking the performance of each construct into account. The 5000 samples show that all the path coefficients are significant, sup- results permit the identification of determinants with a relatively high porting all the hypotheses. Finally, in light of the partial measurement importance and relatively low performance. These determinants with 435 GONG AND YI 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 0.998 0.999 1.000 1.000 0.997 0.999 1.000 tively. When the IPMA results are analyzed, the prioritization of man- 2014). Figures 2–6 show the IPMA results for five countries, respecagerial activities of high importance becomes obvious. 0.999 1.000 1.000 1.000 (Figure 2 shows that in comparison with other service quality dimensions, the performance quality's importance is the highest. In other words, a one-unit increase in the performance quality's performance from 70.22 to 71.22 would increase the performance of customer happiness by 0.47 points. Hence, when managers wish to improve 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 0.999 1.000 1.000 1.000 0.997 1.000 0.997 1.000 0.998 0.997 1.000 More specifically, the importance–performance map for China 1.000 c c 5% Quantile of cu 5% Quantile of cu 5% Quantile of cu that should be addressed by marketing activities (Schloderer et al., the performance of customer happiness by means of overall service 1.000 1.000 ity because this construct has the highest importance among service 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 0.999 0.999 1.000 1.000 0.999 0.998 1.000 5% Quantile of cu c quality, their first priority should be to improve performance qual- that delivery quality has the highest importance among service qual- quality dimensions. On the other hand, Figure 3 for Hong Kong shows ity dimensions but a relatively low performance. Thus, it is obvious 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 Kong. Interestingly, Figure 4 shows that environment quality has the highest importance among service quality dimensions and a relatively high performance in Japan. Thus, improvement of delivery quality is not a top priority in Japan. In addition, Figure 5 shows that in South Korea, delivery quality and performance quality are important, but 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 0.999 1.000 0.999 1.000 0.999 1.000 0.998 1.000 1.000 1.000 c c that improvement of the delivery quality is a top priority for Hong 5% Quantile of cu Hong Kong vs. South Korea Hong Kong vs. Singapore Japan vs. South Korea Japan vs. Singapore South Korea vs. Singapore high importance and low performance are major improvement areas their performance is rather low. Therefore, managers in South Korea 1.000 0.999 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 0.999 0.999 1.000 1.000 0.998 0.999 1.000 Therefore, resources should be equally allocated to service quality sions are rather similar in terms of their importance and performance. dimensions in Singapore. Beyond service quality dimensions, across 1.000 1.000 tomer loyalty has the second highest importance, and overall service quality is the third priority, except for in Japan. In addition to the theoretically hypothesized paths illustrated in Notes: If c < 5% quantile of cu , compositional invariance requirements are violated. 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 Customer happiness Customer loyalty 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 Customer satisfaction 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 0.999 1.000 1.000 1.000 0.998 1.000 1.000 0.999 0.998 1.000 0.999 1.000 0.999 1.000 1.000 1.000 Service quality Environment 0.998 1.000 0.999 1.000 0.998 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 0.998 1.000 0.999 0.998 1.000 0.999 1.000 Delivery c c c sions. Lastly, Figure 6 shows that in Singapore, service quality dimen- five countries, customer satisfaction has the highest importance, cus- Performance c c 5% Quantile of cu 5% Quantile of cu 5% Quantile of cu 5% Quantile of cu 5% Quantile of cu China vs. South Korea China vs. Japan China vs. Hong Kong Variable TA B L E 4 Measurement invariance (MICOM) assessment China vs. Singapore Hong Kong vs. Japan should devote efforts toward improving these service quality dimen- Figure 1 this study also tests the potential moderating effect on the key path in an exploratory way. The current research performs this analysis with customer income, which was measured by asking “how much money does your household earn monthly?” (1 = less than 150 USD, 2 = 151–200 USD, 3 = 201–250 USD, 4 = 251– 300 USD, 5 = 301–400 USD, 6 = 401–500 USD, 7 = 501–600 USD, 8 = 601–700 USD, 9 = 701–800 USD, and 10 = more than 801 USD). Prior research argues that people with higher income tend to be happier than those with lower income because those with higher income are better able to fulfill their aspirations and feel better off (Blanchflower & Oswald, 2004; Easterlin, 2001). Previous research also shows that upper-income customers have lower expectations about service quality than middle- and lower-income customers, which in turn increase customer satisfaction and customer happiness (Scott & Shieff, 1993). Therefore, this study tested the moderating effect of customer income on the relationship between overall service quality and customer happiness mediated by customer satisfaction. A moderated mediation analysis was performed using the PROCESS macro (Model 14; Hayes, 2015), with overall service quality as the independent variable, customer satisfaction as the mediator, customer income as the 436 GONG AND YI TA B L E 5 Results of the country-specific structural model Path relationships China Hong Kong Japan South Korea Singapore H1: Performance→service quality 0.34*** 0.14*** 0.31*** 0.38*** 0.28*** H2: Delivery→service quality 0.35*** 0.48*** 0.25** 0.38*** 0.28** H3: Environment→service quality 0.23*** 0.30*** 0.36*** 0.16* 0.32*** H4: Service quality→customer satisfaction 0.89*** 0.90*** 0.93*** 0.89*** 0.87*** H5: Customer satisfaction→customer loyalty 0.75*** 0.78*** 0.76*** 0.74*** 0.73*** H6: Customer satisfaction→customer happiness 0.35*** 0.48*** 0.18* 0.39*** 0.41*** H7: Customer loyalty→customer happiness 0.50*** 0.34*** 0.69*** 0.44*** 0.48*** R2 Service quality 0.69 0.73 0.71 0.72 0.66 Customer satisfaction 0.80 0.81 0.87 0.80 0.76 Customer loyalty 0.57 0.61 0.59 0.55 0.53 Customer happiness 0.64 0.61 0.71 0.60 0.68 Notes: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. second-stage moderator, and customer happiness as the dependent loyalty, and happiness, are applicable across the five countries in Asia variable. As Table 7 shows, the results suggested a significant inter- considered in this study. The service quality model has been developed action effect between customer satisfaction and customer income in in countries such as the United States and Europe, and there has been a three countries: China, Hong Kong, and South Korea. The index of mod- need for testing this model in Asian countries. By doing so, researchers erated mediation indicated that CI did not include zero in China (CI could examine the applicability of the service quality model to Asian [0.04, 0.07]), Hong Kong (CI [0.00, 0.07]), and South Korea (CI [0.01, countries. The cross-cultural psychology literature suggests that the 0.04]). In other words, the indirect effect of service quality on customer metric invariance and the relationships among constructs in a model happiness via customer satisfaction is moderated by customer income must be established for a model to be applicable across countries in these three countries. In contrast, the index of moderated media- (Durvasula et al., 1993). Accordingly, this study used a national- tion included zero in Japan (CI [−0.04, 0.04]) and Singapore (CI [−0.03, level analysis and a multigroup analysis to examine the model cross- 0.03]), and the interaction effect of customer satisfaction and customer nationally in five Asian countries. The results suggest that overall ser- income was insignificant, suggesting no moderation effect of customer vice quality has a positive influence on customer satisfaction, which in income (Hayes, 2015). turn leads to customer loyalty and customer happiness, and that the To probe the moderation of the indirect effect, a spotlight analysis general pattern of structural relationships is valid for the five countries. was run (Spiller, Fitzsimons, Lynch, & McClelland, 2013). Using the beta Furthermore, the comparisons of paths show that most of them were coefficient estimates, the bottom of Table 7 shows the indirect effect not significantly different across five countries. However, there were of service quality on customer happiness via customer satisfaction at two paths that were significantly different. For instance, the path from low (−1 SD), moderate (mean), and high (+1 SD) levels of customer performance quality to overall service quality was significantly differ- income. Focusing on the three countries with significant moderation ent between China and Hong Kong. In addition, the path from customer effects (i.e., China, Hong Kong, and South Korea), the indirect effects of satisfaction to customer happiness was significantly different between service quality on customer happiness via customer satisfaction were Hong Kong and Japan. all significant at low (−1 SD), moderate (mean), and high (+1 SD) levels It can be noted that this research is the first cross-national com- of customer income. Furthermore, the indirect effect was stronger for parative study of service quality and customer satisfaction in the five customers with higher income. For example, in Hong Kong, the effect is Asian countries. According to a review of cross-cultural customer stud- 0.23 when customer income is low (one SD below the mean), whereas it ies, most previous studies involve only two countries (Sin, Cheung, & is 0.41 when customer income is high (one SD above the mean). A sim- Lee, 1999). Thus, previous studies may have limited value compared ilar pattern was found in China and South Korea. Taken together, cus- to studies done in several countries. Studies done in several countries tomer income seems to increase the effect of service quality on cus- could provide researchers a deeper understanding of the effects of tomer happiness via customer satisfaction in China, Hong Kong, and country on service quality models. Hence, this study empirically exam- South Korea. ined the service quality model using data collected from five Asian countries: China, Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, and Singapore. Overall, the results support the proposed model of service quality for China, 5 CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, and Singapore. As expected, service performance, service delivery, and service environment were found The current study examines whether the relationships between ser- to be determinants of overall service quality perceptions. In addition, vice quality and its consequences, such as customer satisfaction, overall service quality perceptions were found to be a determinant of 0.18 0.26 0.02 0.01 0.16 0.21 Delivery→ service quality Environment→ service quality Service quality→ customer satisfaction Customer satisfaction→ customer loyalty Customer satisfaction→ customer happiness Customer loyalty→ customer happiness Notes: ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. 0.44 Performance→ service quality │diff 0.83 0.93 0.62 0.75 0.99 0.92 0.00*** 0.14 0.14 0.00 0.05 0.33 0.05 0.26 0.91 0.09 0.48 0.97 0.99 0.36 0.02 0.11 0.07 0.03 0.01 0.13 0.08 0.19 0.16 0.72 0.32 0.62 0.84 0.72 0.06 0.07 0.09 0.04 0.01 0.29 0.02 0.29 0.23 0.82 0.26 0.43 0.44 0.44 0.89 0.34 0.30 0.02 0.03 0.07 0.24 0.19 0.99 0.00** 0.38 0.85 0.77 0.93 0.95 0.09 0.09 0.04 0.01 0.14 0.10 0.25 0.77 0.25 0.22 0.43 0.09 0.20 0.99 0.14 0.07 0.05 0.03 0.02 0.21 0.15 0.90 0.24 0.18 0.29 0.58 0.55 0.94 0.25 0.21 0.02 0.04 0.20 0.13 0.07 0.88 0.95 0.97 0.99 0.65 0.95 0.78 0.21 0.22 0.04 0.06 0.04 0.03 0.04 0.92 0.98 0.28 0.11 0.35 0.59 0.37 0.04 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.16 0.10 0.10 0.78 0.99 0.99 0.87 0.43 0.65 0.55 │p-value South Korea vs. Singapore │p-value │diff Japan vs. Singapore │p-value │diff Japan vs. South Korea │p-value │diff Hong Kong vs. Singapore │p-value │diff Hong Kong vs. South Korea │p-value │diff Hong Kong vs. Japan │p-value │diff China vs. Singapore │p-value │diff China vs. South Korea │p-value │diff China vs. Japan │p-value │diff China vs. Hong Kong Multigroup comparison test results Relationship TA B L E 6 GONG AND YI 437 438 GONG AND YI 80 80 75 75 70 Performance Environment SQ 65 CS Delivery 60 Performance Performance Loyalty 55 50 0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 Importance 0.6 0.7 SQ Performance CS Delivery 60 0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 Importance 0.6 0.7 0.8 F I G U R E 5 Importance–performance map analysis for South Korea [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com] 80 75 70 Environment 65 Performance Loyalty 75 Loyalty SQ CS Delivery 60 Performance Performance 65 50 0.8 80 Environment 70 Delivery 65 CS SQ Performance 60 55 55 50 0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 Importance 0.6 0.7 0.8 F I G U R E 3 Importance–performance map analysis for Hong Kong [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com] 80 0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 Importance 0.6 0.7 0.8 F I G U R E 6 Importance–performance map analysis for Singapore [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com] that can be accomplished by means of general convergence (Calantone, Schmidt, & Song, 1996). 75 Performance Loyalty Environment 55 F I G U R E 2 Importance–performance map analysis for China [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com] 50 70 Because of the recent increase in the globalization of the service Loyalty 70 Environment 65 business, marketers have a growing need for cross-national constructs SQ CS and measures that are reliable, valid, and applicable across countries. Globalization of markets has resulted in increased competition among Delivery 60 Asian brands. Maintaining consistently high quality services is a pow- Performance erful means of increasing the overall performance of a global Asian 55 enterprise (Ostrom et al., 2015). Measures with sound psychometric 50 0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 Importance 0.6 0.7 0.8 FIGURE 4 Importance–performance map analysis for Japan [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com] properties across Asian countries will facilitate service marketing strategies in Asian markets (Netemeyer et al., 1991). This study examines the measures of service quality, customer satisfaction, customer loyalty, and customer happiness in a cross-national context. Strong support for these constructs’ psychometric properties is found across five Asian countries. customer satisfaction. Customer satisfaction was found to be a deter- Given recognition of the impact of service marketing on social per- minant of customer loyalty and customer happiness. Finally, customer formance (e.g., transformative service research, customer well-being loyalty was found to be a determinant of customer happiness. These or happiness) (Anderson et al., 2013), the present study represents an results provide strong evidence for the cross-country stability of the important step forward. The results of this study reveal three key find- service quality model (Cadogan, Diamantopoulos, & De Mortanges, ings. First, social performance, such as customer happiness, was driven 1999). Cook and Campbell (1979) note that to demonstrate robust by service quality. This finding makes a key contribution to the service causal relationships, using one sample of respondents is not appropri- literature, extending the understanding of service co-creation beyond ate. The current study tests the model using data collected from five economic indicators. This finding is significant, especially because countries to increase the confidence of a robust causal relationship the role of customer happiness as an outcome of service quality is 439 GONG AND YI TA B L E 7 Conditional indirect effects of service quality on customer happiness through customer satisfaction Country China Predictor Hong Kong Japan South Korea Singapore Effect Customer satisfaction Constant 0.19 0.51** 0.29 0.60*** 1.16*** Service quality 0.95*** 0.92*** 0.96*** 0.91*** 0.84*** Constant 1.18 2.47** 0.89 0.86 0.93 Customer happiness Customer satisfaction 0.36* 0.09 0.25 0.33* 0.36* Service quality 0.41*** 0.51*** 0.47* 0.39*** 0.45*** Income −0.13 0.24* 0.02 −0.04 0.05 CS × Income 0.02* 0.04* 0.01 0.02* −0.00 Income Boot indirect effect −1 SD 0.37 CI [0.15, 0.62] 0.23 CI [0.01, 0.47] 0.26 CI [−0.05, 0.59] 0.35 CI [0.18, 0.57] 0.29 CI [0.11, 0.52] Mean 0.41 CI [0.20, 0.63] 0.32 CI [0.13, 0.56] 0.27 CI [−0.02, 0.57] 0.36 CI [0.22, 0.61] 0.29 CI [0.14, 0.52] +1 SD 0.45 CI [0.21, 0.71] 0.41 CI [0.21, 0.65] 0.30 CI [−0.03, 0.61] 0.43 CI [0.24, 0.65] 0.28 CI [0.13, 0.54] Index of moderated mediation 0.02 CI [0.04, 0.07] 0.03 CI [0.00, 0.07] 0.01 CI [−0.04, 0.04] 0.02 CI [0.01, 0.04] −0.00 CI [−0.03, 0.03] Notes: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. not well investigated, despite the growing interest in transformative service quality and internal processes. The proposed scales could be service, which enhances customer happiness (Garma & Bove, 2011; used as diagnostic tools to identify specific areas where improve- Guo, Arnould, Gruen, & Tang, 2013; Mick, Pettigrew, Pechmann, & ments are needed and pinpoint aspects of the firm's service quality Ozanne, 2012). Apparently, there is a need for firms to move beyond that require work. In addition, the service quality scale can easily be financial performance and evaluate firm performance according to added to the annual satisfaction survey or questionnaires for loyalty social performance. Second, customer loyalty was driven by service programs. Service quality information would be useful for managers in quality across the five Asian countries, demonstrating that the eco- investigating customer happiness or well-being. Databases containing nomic values of service quality could be applied to Asian countries as the level of service quality could be used to enhance the level of cus- well as North American and European countries. Third, individual per- tomer happiness (Hellén & Sääksjärvi, 2011). formance, such as customer satisfaction, was driven by service quality. This paper also shows that customer income can influence the indi- All in all, the present study highlights the crucial role of service quality rect effect of overall service quality on customer happiness through in enhancing social, firm, and individual performances by meeting cus- customer satisfaction. Specifically, customer income is found to mod- tomer needs during service co-creation. This understanding makes an erate the mediating effect of customer satisfaction on customer hap- important contribution to service research. piness. Nevertheless, the moderating effect of customer income var- The findings of this study highlight the value of measuring service ied across countries; the moderation effect was significant in China, quality, primarily because service quality enhances customer satisfac- Hong Kong, and South Korea, but not in Japan and Singapore. That tion, customer loyalty, and customer happiness. The three dimensions is, although the overall service quality model is robust across the of service quality (performance, delivery, and environment) were found countries, the particular moderation effect of customer income varies to influence overall service quality universally for five Asian countries. across the countries. Furthermore, in the three countries where the Nevertheless, the relative importance of the three quality dimensions moderating effect of customer income exists, customer income tends seems to vary slightly across the five countries. Thus, managers should to magnify the effect of customer satisfaction on customer happiness. have flexibility and strategy in resource allocation when they want to That is, as customer income increases, the importance of customer sat- increase overall service quality depending on the countries in which isfaction becomes higher in achieving customer happiness. Consider- they operate. Indeed, performance quality, delivery quality, and envi- ing that little research has investigated the moderating role of cus- ronment quality play a key role in the development of overall service tomer income in the service quality model, the findings of this study quality, which in turn increases customer satisfaction, customer loy- might be meaningful. alty, and customer happiness. Nevertheless, managers should focus This study is not without limitations. It only addresses one service on improving specific service quality dimensions based on the find- (the department store). Future studies should seek to extrapolate the ings of IPMA of this study. For that purpose, managers might want analysis into other service areas. Further research should also con- to segment their Asian customer base according to levels of service sider the role that unobservable traits such as personality or lifestyle quality. Such segmentation would enable firms to allocate a larger play in explaining service quality and customer happiness. It could be amount of resources to customers who need more support in forming argued that segments identified by means of specific unobservable positive customer happiness. Further, they should constantly monitor variables are usually more homogenous and their customers respond 440 consistently to marketing actions, but customers in these segments are difficult to identify from variables that are measured (Schloderer et al., 2014). Using a similar logic, it is possible that the importance of various service quality factors differs with regard to how often they visit the department store due to habituation effects. Future research should therefore consider this issue by segmenting the data along such behavioral variables (Hock et al., 2010). The study also presents a crosssectional evaluation of service quality, but a longitudinal study could enrich the findings and generate a deeper understanding of the dynamics of service quality (Rindfleisch, Malter, Ganesan, & Moorman, 2008). Future research using experiments may detect accurately more the causality between service quality, customer satisfaction, customer loyalty, and customer happiness. ACKNOWLEDGMENT This work was supported by the research fund of Hanyang University (HY-2017-G). ENDNOTE 1 Although Hong Kong is a part of China, it is politically & culturally distinct from China. It is a separately administered region that has its own currency and culture. Hence it is treated as a different country in this paper. REFERENCES Aksoy, L., Keiningham, T. L., Buoye, A., Larivière, B., Williams, L., & Wilson, I. (2015). Does loyalty span domains? Examining the relationship between consumer loyalty, other loyalties and happiness. Journal of Business Research, 68, 2464–2476. Anderson, L., & Ostrom, A. L. (2015). Transformative service research: Advancing our knowledge about service and well-being. Journal of Service Research, 18, 243–249. Anderson, L., Ostrom, A. L., Corus, C., Fisk, R. P., Gallan, A. S., Giraldo, M., … Williams, J. D. (2013). Transformative service research: An agenda for the future. Journal of Business Research, 66, 1203– 1210. Babakus, E., & Boller, G. W. (1992). An empirical assessment of the servqual scale. Journal of Business Research, 24, 253–268. Bagozzi, R. P. (1992). The self-regulation of attitudes, intentions, and behavior. Social Psychology Quarterly, 55, 178–204. Baker, J., Parasuraman, A., Grewal, D., & Voss, G. B. (2002). The influence of multiple store environment cues on perceived merchandise value and patronage intentions. Journal of Marketing, 66, 120–141. Bergkvist, L., & Rossiter, J. R. (2007). The predictive validity of multiple-item versus single-item measures of the same constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 44, 175–184. Bettingen, J.-F., & Luedicke, M. K. (2009). Can brands make us happy? A research framework for the study of brands and their effects on happiness. Advances in Consumer Research, 36, 308–315. Bitner, M. J. (1992). Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. Journal of Marketing, 56, 57–71. Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2004). Well-being over time in Britain and the USA. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 1359–1386. Blut, M. (2016). E-service quality: Development of a hierarchical model. Journal of Retailing, 92, 500–517. GONG AND YI Bolton, R. N., & Drew, J. H. (1991). A multistage model of customers’ assessments of service quality and value. Journal of Consumer Research, 17, 375–384. Brady, M. K., & Cronin, J. J. (2001). Some new thoughts on conceptualizing perceived service quality: A hierarchical approach. Journal of Marketing, 65, 34–49. Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In H. C. Trandis & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology (pp. 389–444). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon. Cadogan, J. W., Diamantopoulos, A., & De Mortanges, C. P. (1999). A measure of export market orientation: Scale development and crosscultural validation. Journal of International Business Studies, 30, 689– 707. Calantone, R. J., Schmidt, J. B., & Song, X. M. (1996). Controllable factors of new product success: A cross-national comparison. Marketing Science, 15, 341–358. Chao, P. (2008). Exploring the nature of the relationships between service quality and customer loyalty: An attribute-level analysis. Service Industries Journal, 28, 95–116. Choi, B. J., & Kim, H. S. (2013). The impact of outcome quality, interaction quality, and peer-to-peer quality on customer satisfaction with a hospital service. Managing Service Quality, 23, 188–204. Collier, J. E., & Bienstock, C. C. (2006). Measuring service quality in eretailing. Journal of Service Research, 8, 260–275. Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (1979). Quasi-experimentation: Design and analysis for field settings. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company. Cronin, J. J., Brady, M. K., & Hult, G. T. M. (2000). Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. Journal of Retailing, 76, 193–218. Cronin, J. J., & Taylor, S. A. (1992). Measuring service quality: A reexamination and extension. Journal of Marketing, 56, 55–68. Dabholkar, P. A. (1996). Consumer evaluations of new technology-based self-service options: An investigation of alternative models of service quality. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 13, 29–51. Dabholkar, P. A., Thorpe, D. I., & Rentz, J. O. (1996). A measure of service quality for retail stores: Scale development and validation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 24, 3–16. Dagger, T. S., & Sweeney, J. C. (2006). The effect of service evaluations on behavioral intentions and quality of life. Journal of Service Research, 9, 3– 18. Dagger, T. S., Sweeney, J. C., & Johnson, L. W. (2007). A hierarchical model of health service quality: Scale development and investigation of an integrated model. Journal of Service Research, 10, 123–142. De Keyser, A., & Lariviere, B. (2014). How technical and functional service quality drive consumer happiness: Moderating influences of channel usage. Journal of Service Management, 25, 30–48. Durvasula, S., Andrews, J. C., Lysonski, S., & Netemeyer, R. G. (1993). Assessing the cross-national applicability of consumer behavior models: A model of attitude toward advertising in general. Journal of Consumer Research, 19, 626–636. Easterlin, R. A. (2001). Income and happiness: Towards a unified theory. Economic Journal, 111, 465–484. Ekinci, Y., & Dawes, P. L. (2009). Consumer perceptions of frontline service employee personality traits, interaction quality, and consumer satisfaction. Service Industries Journal, 29, 503–521. Garma, R., & Bove, L. L. (2011). Contributing to well-being: Customer citizenship behaviors directed to service personnel. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 19, 633–649. Gilbert, D. T. (2005). Stumbling on happiness. New York, NY: Vintage Books. GONG AND YI Grönroos, C. (1984). A service quality model and its marketing implications. European Journal of Marketing, 18, 36–44. Guo, L., Arnould, E. J., Gruen, T. W., & Tang, C. (2013). Socializing to coproduce: Pathways to consumers’ financial well-being. Journal of Service Research, 16, 549–563. Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: SAGE. Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., & Thiele, K. O. (2017). Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45, 616–632. Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50, 1–22. Hellén, K., & Sääksjärvi, M. (2011). Happiness as a predictor of service quality and commitment for utilitarian and hedonic services. Psychology & Marketing, 28, 934–957. Hellier, P. K., Geursen, G. M., Carr, R. A., & Rickard, J. A. (2003). Customer repurchase intention: A general structural equation model. European Journal of Marketing, 37, 1762–1800. 441 Nicolao, L., Irwin, J. R., & Goodman, J. K. (2009). Happiness for sale: Do experiential purchases make consumers happier than material purchases? Journal of Consumer Research, 36, 188–198. Orth, U. R., Limon, Y., & Rose, G. (2010). Store-evoked affect, personalities, and consumer emotional attachments to brands. Journal of Business Research, 63, 1202–1208. Ostrom, A. L., Parasuraman, A., Bowen, D. E., Patrício, L., Voss, C. A., & Lemon, K. (2015). Service research priorities in a rapidly changing context. Journal of Service Research, 18, 127–159. Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1988). SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. Journal of Retailing, 64, 12–40. Park, S.-J., & Yi, Y. (2016). Performance-only measures vs. performanceexpectation measures of service quality. Service Industries Journal, 36, 741–756. Patterson, P. G., Johnson, L. W., & Spreng, R. A. (1997). Modeling the determinants of customer satisfaction for business-to-business professional services. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 25, 4–17. Pollack, B. L. (2009). Linking the hierarchical service quality model to customer satisfaction and loyalty. Journal of Services Marketing, 23, 42–50. Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116, 2–20. Powpaka, S. (1996). The role of outcome quality as a determinant of overall service quality in different categories of services industries: An empirical investigation. Journal of Services Marketing, 10, 5–25. Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43, 115–135. Rindfleisch, A., Malter, A. J., Ganesan, S., & Moorman, C. (2008). Crosssectional versus longitudinal survey research: Concepts, findings, and guidelines. Journal of Marketing Research, 45, 261–279. Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. International Marketing Review, 33, 405–431. Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). Gain more insight from your PLS-SEM results: The importance-performance map analysis. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116, 1865–1886. Hock, C., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2010). Management of multi-purpose stadiums: Importance and performance measurement of service interfaces. International Journal of Services Technology and Management, 14, 188–207. Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Becker, J. M. (2015). SmartPLS 3 [computer software]. Retrieved from https://www.smartpls.com Hofstede, G. H., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind: International cooperation and its importance for survival. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. Hume, M., & Mort, G. S. (2010). The consequence of appraisal emotion, service quality, perceived value and customer satisfaction on repurchase intent in the performing arts. Journal of Services Marketing, 24, 170–182. Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Liang, H., Saraf, N., Hu, Q., & Xue, Y. (2007). Assimilation of enterprise systems: The effect of institutional pressures and the mediating role of top management. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 31, 59– 87. MacKenzie, S. B., Podsakoff, P. M., & Jarvis, C. B. (2005). The problem of measurement model misspecification in behavioral and organizational research and some recommended solutions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 710–729. Mick, D. G., Pettigrew, S., Pechmann, C., & Ozanne, J. L. (2012). Origins, qualities, and envisionment of transformative consumer research. In D. G. Mick, S. Pettigrew, C. Pechmann, & J. L. Ozanne (Eds.), Transformative consumer research for personal and collective well-being (pp. 3–24). New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group. Rossiter, J. R. (2002). The C-OAR-SE procedure for scale development in marketing. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 19, 305– 335. Rust, R. T., & Oliver, R. L. (1994). Service quality: Insights and managerial implications from the frontier. In R. T. Rust & R. L. Oliver (Eds.), Service quality: New directions in theory and practice (pp. 1–19). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., Thiele, K. O., & Gudergan, S. P. (2016). Estimation issues with PLS and CBSEM: Where the bias lies! Journal of Business Research, 69, 3998–4010. Sarstedt, M., Henseler, J., & Ringle, C. M. (2011). Multigroup analysis in partial least squares (PLS) path modeling: Alternative methods and empirical results. In M. Sarstedt, M. Schwaiger, & C. R. Taylor (Eds.), Measurement and research methods in international marketing (Vol. 22, pp. 195– 218). Bingley, England: Emerald Group Publishing. Schloderer, M. P., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2014). The relevance of reputation in the nonprofit sector: The moderating effect of sociodemographic characteristics. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 19, 110–126. Scott, D., & Shieff, D. (1993). Service quality components and group criteria in local government. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 4, 42–53. Neal, J. D., Uysal, M., & Sirgy, M. J. (2007). The effect of tourism services on travelers’ quality of life. Journal of Travel Research, 46, 154–163. Sin, L. Y. M., Cheung, G. W. H., & Lee, R. (1999). Methodology in crosscultural consumer research: A review and critical assessment. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 11, 75–96. Netemeyer, R. G., Durvasula, S., & Lichtenstein, D. R. (1991). A crossnational assessment of the reliability and validity of the CETSCALE. Journal of Marketing Research, 28, 320–327. Sirgy, M. J., Samli, A. C., & Meadow, H. L. (1982). The interface between quality of life and marketing: A theoretical framework. Journal of Marketing & Public Policy, 1, 69–84. 442 Sivakumar, K., Li, M., & Dong, B. (2014). Service quality: The impact of frequency, timing, proximity, and sequence of failures and delights. Journal of Marketing, 78, 41–58. Spiller, S. A., Fitzsimons, G. J., Lynch, J. G., & McClelland, G. H. (2013). Spotlights, floodlights, and the magic number zero: Simple effects tests in moderated regression. Journal of Marketing Research, 50, 277–288. Su, L., Swanson, S. R., & Chen, X. (2016). The effects of perceived service quality on repurchase intentions and subjective well-being of Chinese tourists: The mediating role of relationship quality. Tourism Management, 52, 82–95. GONG AND YI Voorhees, C. M., Brady, M. K., Calantone, R., & Ramirez, E. (2016). Discriminant validity testing in marketing: An analysis, causes for concern, and proposed remedies. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44, 119– 134. Williams, L. J., & Anderson, S. E. (1994). An alternative approach to method effects by using latent-variable models: Applications in organizational behavior research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79, 323–331. Yi, Y., & Gong, T. (2008). The electronic service quality model: The moderating effect of customer self-efficacy. Psychology & Marketing, 25, 587– 601. Sweeney, J. C., Danaher, T. S., & McColl-Kennedy, J. R. (2015). Customer effort in value cocreation activities: Improving quality of life and behavioral intentions of health care customers. Journal of Service Research, 18, 318–335. Yim, C. K., Tse, D. K., & Chan, K. W. (2008). Strengthening customer loyalty through intimacy and passion: Roles of customer-firm affection and customer-staff relationships in services. Journal of Marketing Research, 45, 741–756. Sweeney, J. C., Soutar, G. N., & Johnson, L. W. (1999). The role of perceived risk in the quality-value relationship: A study in a retail environment. Journal of Retailing, 75, 77–105. Zeithaml, V. A., Berry, L. L., & Parasuraman, A. (1996). The behavioral consequences of service quality. Journal of Marketing, 60, 31–46. Szymanski, D. M., & Henard, D. H. (2001). Customer satisfaction: A metaanalysis of the empirical evidence. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 29, 16–35. Taylor, S. A., & Baker, T. L. (1994). An assessment of the relationship between service quality and customer satisfaction in the formation of consumers’ purchase intentions. Journal of Retailing, 70, 163–178. How to cite this article: Gong T, Yi Y. The effect of service quality on customer satisfaction, loyalty, and happiness in five Asian countries. Psychol Mark. 2018;35:427–442. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/mar.21096