(Automation and Control Engineering) Lurie, Boris Enright, Paul - Classical Feedback Control With MATLAB® and Simulink®-CRC Press (2011)

advertisement

Automation and Control

Engineering Series

Classical

Feedback Control

With MATLAB and Simulink

®

SECOND EDITION

Boris J. Lurie and

Paul J. Enright

®

Classical

Feedback Control

With MATLAB and Simulink

®

SECOND EDITION

®

AUTOMATION AND CONTROL ENGINEERING

A Series of Reference Books and Textbooks

Series Editors

FRANK L. LEWIS, Ph.D.,

Fellow IEEE, Fellow IFAC

SHUZHI SAM GE, Ph.D.,

Fellow IEEE

Professor

Automation and Robotics Research Institute

The University of Texas at Arlington

Professor

Interactive Digital Media Institute

The National University of Singapore

Classical Feedback Control: With MATLAB® and Simulink®, Second Edition,

Boris J. Lurie and Paul J. Enright

Synchronization and Control of Multiagent Systems, Dong Sun

Subspace Learning of Neural Networks, Jian Cheng Lv, Zhang Yi, and Jiliu Zhou

Reliable Control and Filtering of Linear Systems with Adaptive Mechanisms,

Guang-Hong Yang and Dan Ye

Reinforcement Learning and Dynamic Programming Using Function

Approximators, Lucian Buşoniu, Robert Babuška, Bart De Schutter,

and Damien Ernst

Modeling and Control of Vibration in Mechanical Systems, Chunling Du

and Lihua Xie

Analysis and Synthesis of Fuzzy Control Systems: A Model-Based Approach,

Gang Feng

Lyapunov-Based Control of Robotic Systems, Aman Behal, Warren Dixon,

Darren M. Dawson, and Bin Xian

System Modeling and Control with Resource-Oriented Petri Nets, Naiqi Wu

and MengChu Zhou

Sliding Mode Control in Electro-Mechanical Systems, Second Edition,

Vadim Utkin, Jürgen Guldner, and Jingxin Shi

Optimal Control: Weakly Coupled Systems and Applications, Zoran Gajić,

Myo-Taeg Lim, Dobrila Skatarić, Wu-Chung Su, and Vojislav Kecman

Intelligent Systems: Modeling, Optimization, and Control, Yung C. Shin

and Chengying Xu

Optimal and Robust Estimation: With an Introduction to Stochastic Control

Theory, Second Edition, Frank L. Lewis, Lihua Xie, and Dan Popa

Feedback Control of Dynamic Bipedal Robot Locomotion, Eric R. Westervelt,

Jessy W. Grizzle, Christine Chevallereau, Jun Ho Choi, and Benjamin Morris

Intelligent Freight Transportation, edited by Petros A. Ioannou

Modeling and Control of Complex Systems, edited by Petros A. Ioannou

and Andreas Pitsillides

Wireless Ad Hoc and Sensor Networks: Protocols, Performance, and Control,

Jagannathan Sarangapani

Stochastic Hybrid Systems, edited by Christos G. Cassandras

and John Lygeros

Hard Disk Drive: Mechatronics and Control, Abdullah Al Mamun,

Guo Xiao Guo, and Chao Bi

Autonomous Mobile Robots: Sensing, Control, Decision Making

and Applications, edited by Shuzhi Sam Ge and Frank L. Lewis

Automation and Control Engineering Series

Classical

Feedback Control

With MATLAB and Simulink

®

SECOND EDITION

Boris J. Lurie and

Paul J. Enright

Boca Raton London New York

CRC Press is an imprint of the

Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

®

MATLAB® is a trademark of The MathWorks, Inc. and is used with permission. The MathWorks does not warrant the

accuracy of the text or exercises in this book. This book’s use or discussion of MATLAB® software or related products

does not constitute endorsement or sponsorship by The MathWorks of a particular pedagogical approach or particular

use of the MATLAB® software.

CRC Press

Taylor & Francis Group

6000 Broken Sound Parkway NW, Suite 300

Boca Raton, FL 33487-2742

© 2012 by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

CRC Press is an imprint of Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business

No claim to original U.S. Government works

Version Date: 20110823

International Standard Book Number-13: 978-1-4398-9746-1 (eBook - PDF)

This book contains information obtained from authentic and highly regarded sources. Reasonable efforts have been

made to publish reliable data and information, but the author and publisher cannot assume responsibility for the validity of all materials or the consequences of their use. The authors and publishers have attempted to trace the copyright

holders of all material reproduced in this publication and apologize to copyright holders if permission to publish in this

form has not been obtained. If any copyright material has not been acknowledged please write and let us know so we may

rectify in any future reprint.

Except as permitted under U.S. Copyright Law, no part of this book may be reprinted, reproduced, transmitted, or utilized in any form by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying, microfilming, and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the

publishers.

For permission to photocopy or use material electronically from this work, please access www.copyright.com (http://

www.copyright.com/) or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923,

978-750-8400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that provides licenses and registration for a variety of users. For

organizations that have been granted a photocopy license by the CCC, a separate system of payment has been arranged.

Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for

identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Visit the Taylor & Francis Web site at

http://www.taylorandfrancis.com

and the CRC Press Web site at

http://www.crcpress.com

Contents

Preface............................................................................................................................................ xiii

To Instructors..................................................................................................................................xv

1. Feedback and Sensitivity.......................................................................................................1

1.1 Feedback Control System.............................................................................................. 1

1.2 Feedback: Positive and Negative.................................................................................3

1.3 Large Feedback............................................................................................................... 4

1.4 Loop Gain and Phase Frequency Responses.............................................................6

1.4.1 Gain and Phase Responses..............................................................................6

1.4.2 Nyquist Diagram..............................................................................................9

1.4.3 Nichols Chart.................................................................................................. 10

1.5 Disturbance Rejection................................................................................................. 12

1.6 Example of System Analysis...................................................................................... 13

1.7 Effect of Feedback on the Actuator Nondynamic Nonlinearity........................... 18

1.8 Sensitivity...................................................................................................................... 19

1.9 Effect of Finite Plant Parameter Variations.............................................................. 21

1.10 Automatic Signal Level Control................................................................................. 21

1.11 Lead and PID Compensators.....................................................................................22

1.12 Conclusion and a Look Ahead................................................................................... 23

Problems................................................................................................................................... 23

Answers to Selected Problems.............................................................................................. 33

2. Feedforward, Multiloop, and MIMO Systems................................................................ 35

2.1 Command Feedforward.............................................................................................. 35

2.2 Prefilter and the Feedback Path Equivalent............................................................. 38

2.3 Error Feedforward....................................................................................................... 39

2.4 Black’s Feedforward Method..................................................................................... 39

2.5 Multiloop Feedback Systems...................................................................................... 41

2.6 Local, Common, and Nested Loops..........................................................................42

2.7 Crossed Loops and Main/Vernier Loops.................................................................43

2.8 Manipulations of Block Diagrams and Calculations of Transfer Functions....................................................................................................... 45

2.9 MIMO Feedback Systems........................................................................................... 48

Problems................................................................................................................................... 51

3. Frequency Response Methods............................................................................................ 57

3.1 Conversion of Time Domain Requirements to Frequency Domain..................... 57

3.1.1 Approximate Relations.................................................................................. 57

3.1.2 Filters................................................................................................................ 61

3.2 Closed-Loop Transient Response..............................................................................64

3.3 Root Locus.....................................................................................................................65

3.4 Nyquist Stability Criterion.......................................................................................... 67

3.5 Robustness and Stability Margins............................................................................. 70

3.6 Nyquist Criterion for Unstable Plant........................................................................ 74

v

vi

Contents

3.7

3.8

Successive Loop Closure Stability Criterion............................................................ 76

Nyquist Diagrams for the Loop Transfer Functions with Poles at

the Origin...................................................................................................................... 78

3.9 Bode Integrals...............................................................................................................80

3.9.1 Minimum Phase Functions...........................................................................80

3.9.2 Integral of Feedback....................................................................................... 82

3.9.3 Integral of Resistance.....................................................................................83

3.9.4 Integral of the Imaginary Part...................................................................... 85

3.9.5 Gain Integral over Finite Bandwidth........................................................... 86

3.9.6 Phase-Gain Relation....................................................................................... 86

3.10 Phase Calculations....................................................................................................... 89

3.11 From the Nyquist Diagram to the Bode Diagram................................................... 91

3.12 Nonminimum Phase Lag............................................................................................ 93

3.13 Ladder Networks and Parallel Connections of m.p. Links.................................... 94

Problems................................................................................................................................... 96

Answers to Selected Problems............................................................................................ 101

4. Shaping the Loop Frequency Response.......................................................................... 103

4.1 Optimality of the Compensator Design................................................................. 103

4.2 Feedback Maximization............................................................................................ 105

4.2.1 Structural Design.......................................................................................... 105

4.2.2 Bode Step........................................................................................................ 106

4.2.3 Example of a System Having a Loop Response with a Bode Step........................................................................................................ 109

4.2.4 Reshaping the Feedback Response............................................................ 118

4.2.5 Bode Cutoff.................................................................................................... 119

4.2.6 Band-Pass Systems........................................................................................ 120

4.2.7 Nyquist-Stable Systems................................................................................ 121

4.3 Feedback Bandwidth Limitations............................................................................ 123

4.3.1 Feedback Bandwidth.................................................................................... 123

4.3.2 Sensor Noise at the System Output............................................................ 123

4.3.3 Sensor Noise at the Actuator Input............................................................ 125

4.3.4 Nonminimum Phase Shift.......................................................................... 126

4.3.5 Plant Tolerances............................................................................................ 127

4.3.6 Lightly Damped Flexible Plants: Collocated and

Noncollocated Control................................................................................. 128

4.3.7 Unstable Plants.............................................................................................. 133

4.4 Coupling in MIMO Systems..................................................................................... 133

4.5 Shaping Parallel Channel Responses...................................................................... 135

Problems................................................................................................................................. 139

Answers to Selected Problems............................................................................................ 142

5. Compensator Design........................................................................................................... 145

5.1 Accuracy of the Loop Shaping................................................................................. 145

5.2 Asymptotic Bode Diagram....................................................................................... 146

5.3 Approximation of Constant Slope Gain Response............................................... 149

5.4 Lead and Lag Links................................................................................................... 150

5.5 Complex Poles............................................................................................................. 152

5.6 Cascaded Links.......................................................................................................... 154

Contents

vii

5.7

5.8

5.9

5.10

Parallel Connection of Links.................................................................................... 157

Simulation of a PID Controller................................................................................. 159

Analog and Digital Controllers............................................................................... 162

Digital Compensator Design.................................................................................... 163

5.10.1 Discrete Trapezoidal Integrator.................................................................. 163

5.10.2 Laplace and Tustin Transforms.................................................................. 165

5.10.3 Design Sequence........................................................................................... 168

5.10.4 Block Diagrams, Equations, and Computer Code................................... 168

5.10.5 Compensator Design Example................................................................... 170

5.10.6 Aliasing and Noise....................................................................................... 174

5.10.7 Transfer Function for the Fundamental.................................................... 176

Problems................................................................................................................................. 177

Answers to Selected Problems............................................................................................ 182

6. Analog Controller Implementation................................................................................. 191

6.1 Active RC Circuits...................................................................................................... 191

6.1.1 Operational Amplifier.................................................................................. 191

6.1.2 Integrator and Differentiator....................................................................... 193

6.1.3 Noninverting Configuration....................................................................... 194

6.1.4 Op-Amp Dynamic Range, Noise, and Packaging................................... 195

6.1.5 Transfer Functions with Multiple Poles and Zeros.................................. 196

6.1.6 Active RC Filters............................................................................................ 198

6.1.7 Nonlinear Links............................................................................................ 200

6.2 Design and Iterations in the Element Value Domain........................................... 202

6.2.1 Cauer and Foster RC Two-Poles.................................................................. 202

6.2.2 RC-Impedance Chart.................................................................................... 205

6.3 Analog Compensator, Analog or Digitally Controlled........................................ 207

6.4 Switched-Capacitor Filters........................................................................................ 208

6.4.1 Switched-Capacitor Circuits........................................................................ 208

6.4.2 Example of Compensator Design............................................................... 208

6.5 Miscellaneous Hardware Issues.............................................................................. 210

6.5.1 Ground........................................................................................................... 210

6.5.2 Signal Transmission..................................................................................... 211

6.5.3 Stability and Testing Issues......................................................................... 213

6.6 PID Tunable Controller............................................................................................. 214

6.6.1 PID Compensator.......................................................................................... 214

6.6.2 TID Compensator......................................................................................... 216

6.7 Tunable Compensator with One Variable Parameter........................................... 218

6.7.1 Bilinear Transfer Function........................................................................... 218

6.7.2 Symmetrical Regulator................................................................................ 219

6.7.3 Hardware Implementation.......................................................................... 220

6.8 Loop Response Measurements................................................................................ 221

Problems.................................................................................................................................225

Answers to Selected Problems............................................................................................ 229

7. Linear Links and System Simulation.............................................................................. 231

7.1 Mathematical Analogies........................................................................................... 231

7.1.1 Electromechanical Analogies...................................................................... 231

viii

Contents

7.1.2 Electrical Analogy to Heat Transfer...........................................................234

7.1.3 Hydraulic Systems........................................................................................ 235

7.2 Junctions of Unilateral Links.................................................................................... 237

7.2.1 Structural Design.......................................................................................... 237

7.2.2 Junction Variables......................................................................................... 237

7.2.3 Loading Diagram.......................................................................................... 238

7.3 Effect of the Plant and Actuator Impedances on the Plant Transfer

Function Uncertainty................................................................................................ 239

7.4 Effect of Feedback on the Impedance (Mobility)................................................... 241

7.4.1 Large Feedback with Velocity and Force Sensors.................................... 241

7.4.2 Blackman’s Formula..................................................................................... 242

7.4.3 Parallel Feedback.......................................................................................... 243

7.4.4 Series Feedback............................................................................................. 243

7.4.5 Compound Feedback................................................................................... 244

7.5 Effect of Load Impedance on Feedback.................................................................. 245

7.6 Flowchart for Chain Connection of Bidirectional Two-Ports.............................. 246

7.6.1 Chain Connection of Two-Ports.................................................................. 246

7.6.2 DC Motors...................................................................................................... 249

7.6.3 Motor Output Mobility................................................................................ 250

7.6.4 Piezoelements................................................................................................ 251

7.6.5 Drivers, Transformers, and Gears.............................................................. 251

7.6.6 Coulomb Friction.......................................................................................... 253

7.7 Examples of System Modeling.................................................................................254

7.8 Flexible Structures..................................................................................................... 257

7.8.1 Impedance (Mobility) of a Lossless System.............................................. 257

7.8.2 Lossless Distributed Structures.................................................................. 258

7.8.3 Collocated Control........................................................................................ 259

7.8.4 Noncollocated Control................................................................................. 260

7.9 Sensor Noise............................................................................................................... 260

7.9.1 Motion Sensors.............................................................................................. 260

7.9.1.1 Position and Angle Sensors......................................................... 260

7.9.1.2 Rate Sensors................................................................................... 261

7.9.1.3 Accelerometers.............................................................................. 262

7.9.1.4 Noise Responses............................................................................ 262

7.9.2 Effect of Feedback on the Signal-to-Noise Ratio...................................... 263

7.10 Mathematical Analogies to the Feedback System................................................. 264

7.10.1 Feedback-to-Parallel-Channel Analogy.................................................... 264

7.10.2 Feedback-to-Two-Pole-Connection Analogy............................................ 264

7.11 Linear Time-Variable Systems.................................................................................. 265

Problems................................................................................................................................. 267

Answers to Selected Problems............................................................................................ 271

8. Introduction to Alternative Methods of Controller Design....................................... 273

8.1 QFT............................................................................................................................... 273

8.2 Root Locus and Pole Placement Methods.............................................................. 275

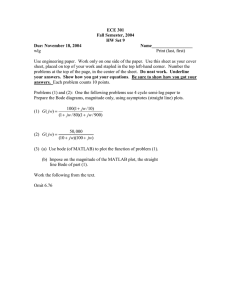

8.3 State-Space Methods and Full-State Feedback...................................................... 277

8.3.1 Comments on Example 8.3.......................................................................... 280

8.4 LQR and LQG............................................................................................................. 282

8.5 H∞, µ-Synthesis, and Linear Matrix Inequalities................................................... 283

Contents

ix

9. Adaptive Systems................................................................................................................ 285

9.1 Benefits of Adaptation to the Plant Parameter Variations................................... 285

9.2 Static and Dynamic Adaptation............................................................................... 287

9.3 Plant Transfer Function Identification.................................................................... 288

9.4 Flexible and n.p. Plants.............................................................................................. 288

9.5 Disturbance and Noise Rejection............................................................................ 289

9.6 Pilot Signals and Dithering Systems....................................................................... 291

9.7 Adaptive Filters.......................................................................................................... 292

10. Provision of Global Stability............................................................................................ 295

10.1 Nonlinearities of the Actuator, Feedback Path, and Plant................................... 295

10.2 Types of Self-Oscillation........................................................................................... 297

10.3 Stability Analysis of Nonlinear Systems................................................................ 298

10.3.1 Local Linearization....................................................................................... 298

10.3.2 Global Stability.............................................................................................. 299

10.4 Absolute Stability.......................................................................................................300

10.5 Popov Criterion.......................................................................................................... 301

10.5.1 Analogy to Passive Two-Poles’ Connection.............................................. 301

10.5.2 Different Forms of the Popov Criterion.....................................................304

10.6 Applications of Popov Criterion..............................................................................305

10.6.1 Low-Pass System with Maximum Feedback............................................305

10.6.2 Band-Pass System with Maximum Feedback........................................... 306

10.7 Absolutely Stable Systems with Nonlinear Dynamic Compensation................306

10.7.1 Nonlinear Dynamic Compensator............................................................. 306

10.7.2 Reduction to Equivalent System................................................................. 307

10.7.3 Design Examples........................................................................................... 309

Problems................................................................................................................................. 317

Answers to Selected Problems............................................................................................ 320

11. Describing Functions.......................................................................................................... 323

11.1 Harmonic Balance...................................................................................................... 323

11.1.1 Harmonic Balance Analysis........................................................................ 323

11.1.2 Harmonic Balance Accuracy....................................................................... 324

11.2 Describing Function.................................................................................................. 325

11.3 Describing Functions for Symmetrical Piece-Linear Characteristics................ 327

11.3.1 Exact Expressions......................................................................................... 327

11.3.2 Approximate Formulas................................................................................ 330

11.4 Hysteresis.................................................................................................................... 331

11.5 Nonlinear Links Yielding Phase Advance for Large-Amplitude Signals.......................................................................................................................... 335

11.6 Two Nonlinear Links in the Feedback Loop.......................................................... 336

11.7 NDC with a Single Nonlinear Nondynamic Link................................................ 337

11.8 NDC with Parallel Channels....................................................................................340

11.9 NDC Made with Local Feedback.............................................................................342

11.10 Negative Hysteresis and Clegg Integrator.............................................................345

11.11 Nonlinear Interaction between the Local and the Common

Feedback Loops..........................................................................................................346

11.12 NDC in Multiloop Systems......................................................................................348

x

Contents

11.13 Harmonics and Intermodulation............................................................................. 349

11.13.1 Harmonics...................................................................................................... 349

11.13.2 Intermodulation............................................................................................ 350

11.14 Verification of Global Stability................................................................................. 351

Problems................................................................................................................................. 353

Answers to Selected Problems............................................................................................ 356

12. Process Instability............................................................................................................... 359

12.1 Process Instability...................................................................................................... 359

12.2 Absolute Stability of the Output Process................................................................ 360

12.3 Jump Resonance......................................................................................................... 362

12.4 Subharmonics............................................................................................................. 365

12.4.1 Odd Subharmonics....................................................................................... 365

12.4.2 Second Subharmonic.................................................................................... 367

12.5 Nonlinear Dynamic Compensation........................................................................ 368

Problems................................................................................................................................. 368

13. Multiwindow Controllers.................................................................................................. 371

13.1 Composite Nonlinear Controllers........................................................................... 372

13.2 Multiwindow Control................................................................................................ 373

13.3 Switching from Hot Controllers to a Cold Controller.......................................... 375

13.4 Wind-Up and Anti-Wind-Up Controllers.............................................................. 377

13.5 Selection Order........................................................................................................... 380

13.6 Acquisition and Tracking.......................................................................................... 381

13.7 Time-Optimal Control.............................................................................................. 383

13.8 Examples.....................................................................................................................384

Problems................................................................................................................................. 388

Appendix 1: Feedback Control, Elementary Treatment...................................................... 391

Appendix 2: Frequency Responses......................................................................................... 405

Appendix 3: Causal Systems, Passive Systems, and Positive Real Functions................ 419

Appendix 4: Derivation of Bode Integrals............................................................................. 421

Appendix 5: Program for Phase Calculation......................................................................... 429

Appendix 6: Generic Single-Loop Feedback System.......................................................... 433

Appendix 7: Effect of Feedback on Mobility........................................................................ 437

Appendix 8: Dependence of a Function on a Parameter..................................................... 439

Appendix 9: Balanced Bridge Feedback................................................................................. 441

Appendix 10: Phase-Gain Relation for Describing Functions..........................................443

Appendix 11: Discussions.........................................................................................................445

Appendix 12: Design Sequence............................................................................................... 459

Appendix 13: Examples............................................................................................................. 461

Contents

xi

Appendix 14: Bode Step Toolbox.............................................................................................505

Bibliography................................................................................................................................. 529

Notation........................................................................................................................................ 533

Preface

Classical Feedback Control presents practical single-input single-output and multi-input

multi-output analog and digital feedback systems. Most examples are from space systems

developed by the authors at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California. The word

classical refers to the system’s frequency response.

The system analysis must be simplified before the system is synthesized. Here the Bode

integral relations play a key role for formulating the optimal system parameters—stability, stability margins, nonlinear stability, and process stability—and designing the loop

compensators.

The compensators in the loop responses are typically linear. The improved nonlinear

compensators are mainly included for adjusting the system at the lowest frequencies and

for using multi-input multi-output systems with different limit frequencies.

The whole engineering system performance would be optimal if each controller within

the subsystems were optimal. Bode integrals allow the responses to be optimized in the

final design stage, thus simplifying the whole procedure.

MATLAB® with Simulink and SPICE are used for the frequency responses. No preliminary experience with this software is presupposed in this book.

The first six chapters support linear control systems. Other chapters consider nonlinear

control, robustness, global stability, and complex system simulation.

It was the authors’ intention to make Classical Feedback Control not only a textbook but

also a reference for students becoming engineers, enabling them to design high-performance controllers and easing the transition from school to the competitive industrial

environment.

The second edition introduces various updates, in particular Simulink calculations of

the stability of a superheterodyne optical receiver, discussions of a system’s nonlinear

voltage-current response, a system’s active vibration isolation, design of a longer antenna

control, attitude regulation errors, and a multioutput optical receiver.

We will be grateful for any comments, corrections, and criticism our readers may take

the trouble to communicate to us by e-mail (bolurie@gmail.com) or addressed to B. J. Lurie,

2738 Orange Avenue, La Crescenta, CA 91214.

Acknowledgments. We thank Alla Roden for technical editing and acknowledge the help

of Asif Ahmed. We appreciate previous discussions on many control issues with Professor

Isaac Horowitz, and collaboration, comments, and advice of our colleagues at the Jet

Propulsion Laboratory.

We thank Drs. Alexander Abramovich, John O’Brien, David Bayard (who helped edit the

chapter on adaptive systems), Dhemetrio Boussalis, Daniel Chang, Gun-Shing Chen (who

contributed Appendix 7), Ali Ghavimi (who contributed to Section A13.14 of Appendix

13), Fred Hadaegh (who coauthored several papers in Chapter 13), John Hench, Mehran

Mesbahi, Jason Modisette (who suggested many changes and corrections), Gregory Neat,

Samuel Sirlin, and John Spanos. We are grateful to Edward Kopf, who told the authors

about the jump resonance in the attitude control loop of the Mariner 10 spacecraft, and

to George Rappard, who helped with the second edition. Suggestions and corrections

made by Profs. Randolph Beard, Arthur Lanne, Roy Smith, and Michael Zak allowed us

xiii

xiv

Preface

to improve the manuscript. Alan Schier contributed the example of a mechanical snake

control. To all of them we extend our sincere gratitude.

Boris J. Lurie

Paul J. Enright

To Instructors

The book presents the design techniques that the authors found most useful in designing

control systems for industry, telecommunications, and space programs. It also prepares

the reader for research in the area of high-performance nonlinear controllers.

Plant and compensator. Classical design does not utilize the plant’s internal variables

for compensation, unlike the full-state feedback approach. The stand-alone compensator

achieves the feedback loop responses. These are the reasons why this book starts with

feedback, disturbance rejection, loop shaping, and compensator design. The plant modeling is used for the system without the feedback.

Book architecture. The material contained in this book is organized as a sequence of,

roughly speaking, four design layers. Each layer considers linear and nonlinear systems,

feedback, modeling, and simulation, including the following:

1. Control system analysis: Elementary linear feedback theory, a short description of the

effects of nonlinearities, and elementary simulation methods (Chapters 1 and 2).

2. Control system design: Feedback theory and design of linear single-loop systems

developed in depth (Chapters 3 and 4), followed by implementation methods

(Chapters 5 and 6).

This completes the first one-semester course in control.

3. Integration of linear and nonlinear subsystem models into the system model, utilization of the effects of feedback on impedances, various simulation methods

(Chapter 7), followed by a brief survey of alternative controller design methods

and of adaptive systems (Chapters 8 and 9).

4. Nonlinear systems study with practical design methods (Chapters 10 and 11),

methods of elimination or reduction of process instability (Chapter 12), and composite nonlinear controllers (Chapter 13).

Each consecutive layer is based on the preceding layers. For example, introduction of

absolute stability and Nyquist stable systems in the second layer is preceded by a primitive

treatment of saturation effects in the first layer; global stability and absolute stability are

then treated more precisely in the fourth layer. Treatment of the effects of links’ input and

output impedances on the plant uncertainty in the third layer is based on the elementary

feedback theory of the first layer and the effects of plant tolerances on the available feedback developed in the second layer.

This architecture reflects the theory of the system without excessive idealization.

Design examples. The examples of the controllers were chosen among those designed by

the authors for the various space robotic missions at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory:

• An optical receiver for multichannel space system control (Section 2.9.5).

• A prototype for the controller for a retroreflector carriage and several other controllers of the Chemistry spacecraft (Section 4.2.3). All these controllers are high-order

xv

xvi

To Instructors

and nonlinear control plants with structural modes, and include a high-order linear part with a Bode step.

• A nonlinear digital controller for the Mars Pathfinder high-gain antenna pointing

to Earth (Section 5.10.5).

• A switched-capacitor controller for the STRV spacecraft cryogenic cooler vibration

rejection (Section 6.4.2).

• Vibration damping in the model of a space stellar interferometer (Examples 7.2

and 7.20).

• Mars Global Surveyor attitude control (briefly described in Example 3.3,

Section 13.6).

• Microgravity accelerometer analog feedback loop (described in detail in

Example 11.12).

• Cassini Narrow View Camera thermal control (described in detail in Section 7.1.2

and in Example 3, Section 13.6).

• More design examples are described in Appendix 13 and 14.

Software. Most design examples in the book use MATLAB® from MathWorks, Inc. Only

a small subset of MATLAB commands is used, listed below in the order of their introduction: logspace, bode, conv, tf2zp, zp2tf, step, gtext, title, set, grid, hold on, hold off, rlocus,

plot(x,y), inv, linspace, lp2lp, lp2bp, format, roots, poly, inv, bilinear, residue, ezplot, linmod,

laplace, invlaplace, impulse.

Additional MATLAB functions written by the authors and described in Appendix 14

may complement the control design methods.

The Simulink problems are used with the same programs as the MATLAB. Simulink is

employed for repetition and adjustments of the program. For the single run during control

course exercises we prefer using MATLAB.

Simulink should obtain the transient responses and plot Bode diagrams from the block

diagrams (on p. 160).

Use of the SPICE is taught to EE majors for combining conventional design and control

system simulation. Some C code examples are demonstrated in Chapter 5.

Frequency responses. The design methods taught in this book are based on frequency responses.

The transforms are performed numerically with MATLAB commands step and impulse.

EE students know the frequency responses from the signals and systems course, the prerequisite to the control course. Mechanical, chemical, and aerospace engineering majors

know frequency responses from the courses on dynamic responses. If needed, frequency

responses for these specialties can be taught using Appendix 2, either before or in parallel

with Chapter 3. Appendix 2 contains a number of problems on the Laplace transform and

frequency responses.

Undergraduate course. The first six chapters, which constitute the first course in control,

also include some material better suited for a graduate course. This material should be

omitted from a one-semester course, especially when the course is taught to mechanical,

aerospace, and chemical engineering majors when extra time is needed to teach frequency

responses. The sections to be bypassed are listed in the beginning of each chapter.

Digital controllers. The best way of designing a good discrete controller is to design a highorder continuous controller, break it properly into several links, and then convert each link

to a digital form; thus, two small tables of formulas or a MATLAB command are all that is

needed. The accuracy of the Tustin transform is adequate and needs no prewarping.

To Instructors

xvii

The implementation of analog controller. The analog controllers of Chapter 6 are commonly

easier and cheaper to design, and they are important for all engineers. The chapter need

not be fully covered, but can be used for self-study or as a reference later, when the need

for practical design arises.

Second one-semester course. Chapters 7–13 are used for the control course and for selfstudy and as a reference for engineers who took only the first course.

Chapter 7 describes structural design and simulation systems with drivers, motors,

and sensors. In particular, it shows that tailoring the output impedance of the actuator is

important to reduce the plant tolerances and to increase the feedback in the outer loop.

Chapter 8 gives a short introduction to quantitative feedback theory and H∞ control and

the time domain control based on state variables.

Adaptive systems are described briefly since the control systems rarely need to be

applied. But the need for adaptive systems does exist. Therefore, the engineer should be

aware of the major concepts, advantages, and limitations of adaptive control. He or she

must be able to recognize the need for such control and, at the same time, not waste time

trying to achieve the impossible. The material in Chapter 9 will enable engineers either to

figure out how to design an adaptive system themselves, or to understand the language of

the specialized literature.

The design of high-order nonlinear controllers is covered in Chapters 10–13. These

design methods have been proven very effective in practice but are far from being finalized. Further research needs to be done to advance these methods.

Problems. Design problems with mechanical plants are suitable for both ME and EE

majors. Additional problems for EE majors can be found in [9].

A booklet with solutions to the problems is available for instructors from the publisher.

1

Feedback and Sensitivity

Chapter 1 introduces the basics of feedback control. The purpose of feedback is to make

the output insensitive to plant parameter variations and disturbances. Negative, positive,

and large feedback are defined and discussed along with sensitivity and disturbance rejection. The notions of frequency response, the Nyquist diagram, and the Nichols chart are

introduced. (The Nyquist stability criterion is presented in Chapter 3.)

Feedback control and block diagram algebra are explained at an elementary level in

Appendix 1, which can be used as an introduction to this chapter. Laplace transfer functions are described in Appendix 2.

1.1 Feedback Control System

It is best to begin with an example describing the explanation of feedback. Figure 1.1a

depicts a servomechanism regulating the elevation of an antenna.

The output of the feedback summer is called the error. The error amplified by the compensator C is applied to the actuator A, in this case a motor regulator (driver) and a motor.

The motor rotates the plant P, the antenna itself, which is the object of the control. The compensator, actuator, and plant make up the forward path with the transfer function CAP.

Figure 1.1b shows the Simulink block diagram made of cascaded elements, i.e., links.

The letters here stand for the signals’ Laplace transforms and for the functions of the linear

links. The diagram is single-input single-output (SISO) since only one is the commanded

elevation angle U1 and one is the actual output antenna elevation U2.

Commanded

elevation

–

+

Error

Actuator

Compensator

Driver

Measured elevation

Elevation

Motor

Plant

Feed back path,

elevation angle sensor

(a)

U1

–

+

E

T

C

CE

A

BU2, or TE

CAE

P

U2

B

(b)

FIGURE 1.1

Single-loop feedback system.

1

2

Classical Feedback Control: With MATLAB® and Simulink®

It is referred to as single loop. The feedback path contains a sensor B.

The loop transfer function T = CAPB is also called the return ratio of BU2/E.

The return signal that goes into the summer from the feedback path is TE.

The error E = U1 – BU2 is measured at the output of the summer. It is also seen as the signal

E = U1 – ET

(1.1)

The error is therefore expressed as

E=

U1

U

= 1

T +1 F

(1.2)

where F = T + 1 is the return difference. The magnitude |F| is the feedback. It is seen that

when the feedback is large, the error is small.

If the feedback path were not present, the output U2 would simply equal the product

CAPU1. The system would be referred to as open loop.

Example 1.1

A servomechanism for steering a toy car (using wires) is shown in Figure 1.2. The command voltage U1 is regulated by a joystick potentiometer. Another identical potentiometer (angle sensor)

placed on the shaft of the motor produces voltage Uangle proportional to the shaft rotation angle.

The feedback makes the error small, so that the sensor voltage approximates the input voltage, and

therefore the motor shaft angle tracks the joystick-commanded angle.

The arrangement of a motor with an angle sensor is often called servomotor, or simply servo.

Similar servos are used for animation purposes in movie production.

The system of regulating aircraft control surfaces using joysticks and servos was termed “fly by

wire” when it was first introduced to replace bulky mechanical gears and cables. The required

high reliability was achieved by using four independent parallel analog electrical circuits.

The telecommunication link between the control box and the servo can certainly also be wireless.

Example 1.2

A phase-locked loop (PLL) is drawn as Simulink in Figure 1.3. The plant here is a voltage-controlled oscillator (VCO).

The VCO is an ac generator whose frequency is proportional to the voltage applied to its input.

The phase detector combines the functions of phase sensors and input summer: its output is proportional to the phase difference between the input signal and the output of the VCO.

Toy car

Control box

Joystick

Wires

FIGURE 1.2

Joystick control of a steering mechanism.

U1

+

–

Uangle

Angle

sensor

Steering

mechanism

3

Feedback and Sensitivity

Phase of input

periodic signal

Phase

Phase error

detector

Compensator

Voltage

control

VCO

Output periodic signal

Phase of

the signal

FIGURE 1.3

Phase-locked loop.

Large feedback makes the phase difference (phase error) small. The VCO output therefore has a

small phase difference compared with the input signal. In other words, the PLL synchronizes the

VCO with the input periodic signal.

It is very important to also reduce the noise that appears at the VCO output.

The PLLs are widely used in telecommunications (for tuning receivers and for recovering the

computer clock from a string of digital data), for synchronizing several motors’ angular positions

and velocities, and for many other purposes.

1.2 Feedback: Positive and Negative

The output signal in Figure 1.1b is U2 = ECAP, and from Equation 1.2, U1 = EF. The inputto-output transfer function of the system U2/U1, commonly referred to as the closed-loop

transfer function, is

U 2 ECAP CAP

=

=

U1

EF

F

(1.3)

or, the feedback reduces the input-output signal transmission by the factor |F|.

The system is said to have negative feedback when |F| > 1 (although the expression |F|

is certainly positive). This definition was developed in the 1920s and has to do with the fact

that negative feedback reduces the error |E| and the output |U2|, i.e., produces a negative

increment in the output level when the level is expressed in logarithmic values (in dB, for

example) preferred by engineers.

The feedback is said to be positive if |F| < 1, which makes |E| > |U1|. Positive feedback

increases the error and the level of the output.

We will adhere to these definitions of negative and positive feedback since very important theoretical developments, to be studied in Chapters 3 and 4, are based on them.

Whether the feedback is positive or negative depends on the amplitude and phase of the

return ratio (and not only on the sign at the feedback summer, as is stated sometimes in

elementary treatments of feedback).

Let’s consider several numerical examples.

Example 1.3

The forward path gain coefficient CAP is 100, and the feedback path coefficient B is – 0.003.

The return ratio T is – 0.3. Hence, the return difference F is 0.7, the feedback is positive, and the

closed-loop gain coefficient 100/0.7 = 143 is greater than the open-loop gain coefficient.

4

Classical Feedback Control: With MATLAB® and Simulink®

Example 1.4

The forward path gain coefficient is 100, and the feedback path coefficient is 0.003. The return

ratio T is 0.3. Hence, the return difference F is 1.3, the feedback is negative, and the closed-loop

gain coefficient 100/1.3 = 77 is less than the open-loop gain coefficient.

It is seen that when T is small, whether the feedback is positive or negative depends on the sign

of the transfer function about the loop.

When |T | > 2, then |T + 1| > 1 and the feedback is negative. That is, when |T| is large, the feedback is always negative.

Example 1.5

The forward path gain coefficient is 1,000 and B = 0.1. The return ratio is therefore 100. The return

difference is 101, the feedback is negative, and the closed‑loop gain coefficient is 9.9.

Example 1.6

In the previous example, the forward path transfer function is changed to –1,000, and the return

ratio becomes –100. The return difference is –99, the feedback is still negative, and the closedloop gain coefficient is 10.1.

1.3 Large Feedback

Multiplying the numerator and denominator of Equation 1.3 by B yields another meaningful formula:

U2 1 T 1

=

= M

U1 B F B

(1.4)

where

M=

T

T

=

F T +1

(1.5)

Equation 1.4 indicates that the closed-loop transfer function is the inverse of the feedback path transfer function multiplied by the coefficient M. When the feedback is large, i.e.,

when |T| >> 1, the return difference F ≈ T, the coefficient M ≈ 1, and the output becomes

U2 ≈

1

U1

B

(1.6)

One result of large feedback is that the closed-loop transfer function depends nearly

exclusively on the feedback path, which can usually be constructed of precise components. This feature is of fundamental importance since the parameters of the actuator and

the plant in the forward path typically have large uncertainties. In a system with large

5

Feedback and Sensitivity

U1

+

CAP

U2

U1

Error

+

104

–

U2

–

(a)

(b)

FIGURE 1.4

(a) Tracking system. (b) Voltage follower.

feedback, the effect of these uncertainties on the closed-loop characteristics is small. The

larger the feedback, the smaller the error expressed by Equation 1.2.

Manufacturing an actuator that is sufficiently powerful and precise to handle the plant

without feedback can be prohibitively expensive or impossible. An imprecise actuator may

be much cheaper, and a precise sensor may also be relatively inexpensive. Using feedback,

the cheaper actuator and the sensor can be combined to form a powerful, precise, and

reasonably inexpensive system.

According to Equation 1.6, the antenna elevation angle in Figure 1.1 equals the command

divided by B. If the elevation angle is required to be q, then the command should be Bq.

If B = 1, as shown in Figure 1.4a, then the closed-loop transfer function is just M and

U2 ≈ U1; i.e., the output U2 follows (tracks) the commanded input U1. Such tracking systems are widely used. Examples are a telescope tracking a star or a planet, an antenna

on the roof of a vehicle tracking the position of a knob rotated by the operator inside the

vehicle, and a cutting tool following a probe on a model to be copied.

Example 1.7

Figure 1.4b shows an amplifier with unity feedback. The error voltage is the difference between

the input and output voltages. If the amplifier gain coefficient is 104, the error voltage constitutes

only 10 –4 of the output voltage. Since the output voltage nearly equals the input voltage, this

arrangement is commonly called a voltage follower.

Example 1.8

Suppose that T = 100, so that M = T/(T + 1) = 0.9901. If P were to deviate from its nominal value

by +10%, then T would become 110. This would make M = 0.991, an increase of 0.1%, which is

reflected in the output signal. Without the feedback, the variation of the output signal would be

10%. Therefore, introduction of negative feedback in this case reduces the output signal variations

100 times. Introducing positive feedback would do just the opposite—it would increase the variations in the closed-loop input-output transfer function.

Example 1.9

Consider the voltage regulator shown in Figure 1.5a with its block diagram shown in Figure 1.5b.

Here, the differential amplifier with transimpedance (ratio of output current I to input voltage E)

10 A/V and high input and output impedances plays the dual role of compensator and actuator.

The power supply voltage is VCC. The plant is the load resistor RL. The potentiometer with the

voltage division ratio B constitutes the feedback path.

6

Classical Feedback Control: With MATLAB® and Simulink®

U1

E

VCC

+

10 A/V

–

I

RL

U2

TE

U1

+

–

B

(a)

I

10

RL

U2

B

(b)

FIGURE 1.5

Voltage regulator: (a) schematic diagram, (b) block diagram.

The amplifier input voltage is the error E = U1 – TE, and the return ratio is T = 10BRL. Assume

that the load resistor is 1 kΩ and the potentiometer is set to B = 0.5. Consequently, the return ratio

is T = 5,000.

The command is the 5 V input voltage (when the command is constant, as in this case, it is

commonly called a reference, and the control system is called a regulator). Hence, the output

voltage according to Equation 1.4 is 10 × 5,000/5,001 = 9.998 V. The VCC should be higher than

this value; 12 V to 30 V would be appropriate.

When the load resistance is reduced by 10%, without the feedback the output voltage will be 10% less. With the feedback, T decreases by 10% and the output voltage is

10 × 4,500/4,501 ≈ 9.99778, i.e., only 0.002% less. The feedback reduces the output voltage

variations 10%/0.002% = 5,000 times.

This example also illustrates another feature of feedback. Insensitivity of the output voltage to the loading indicates that the regulator output resistance is very low. The feedback

dramatically alters the output impedance from very high to very low. (The same is true for

the follower shown in Figure 1.4b.) The effects of feedback on impedance will be studied

in detail in Chapter 7.

1.4 Loop Gain and Phase Frequency Responses

1.4.1 Gain and Phase Responses

The sum (or the difference) of sinusoidal signals of the same frequency is a sinusoidal

signal with the same frequency. The summation is simplified when the sinusoidal signals

are represented by vectors on a complex plane. The modulus of a vector equals the signal

amplitude and the phase of the vector equals the phase shift of the signal.

Signal u1 = |U1|sin(ωt + ϕ1) is represented by the vector U1 = |U1|∠ϕ1, i.e., by the complex

number U1 = |U1|cosϕ1 + j|U1|sinϕ1.

Signal u2 = |U2|sin(ωt + ϕ2) is represented by the vector U2 = |U2|∠ϕ2, i.e., by the complex

number U2 = |U2|cosϕ2 + j|U2|sinϕ2.

The sum of these two signals is

u = |U |sin(ωt + ϕ) = (|U1|cosϕ1 +|U2|cosϕ2)sinωt + (|U1|sinϕ1 + |U2|sinϕ2)cosωt

7

Feedback and Sensitivity

E

U1

E

TE

U1

(a)

U1

TE

(b)

TE

E

E

U1

TE

(c)

(d)

FIGURE 1.6

Examples of phasor diagrams for (a,b) positive and (c,d) negative feedback.

That is, ReU = ReU1 + ReU2 and ImU = ImU1 + ImU2, i.e., U = U1 + U2. Thus, the vector for

the sum of the signals equals the sum of the vectors for the signals.

Example 1.10

If u1 = 4sin(ωt + π/6), it is represented by the vector 4∠π/6, or 3.464 + j2. If u2 = 6 sin(ωt + π/4), it

is represented by the vector 6∠π/4, or 4.243 + j4.243. The sum of these two signals is represented

by the vector (complex number) 7.707 + j6.243 = 9.92∠0.681 rad or 9.92∠39.0°.

Example 1.11

Figure 1.6 shows four possible vector diagrams U1 = E + TE of the signals at the feedback summer at some frequency. In cases (a) and (b), the presence of feedback signal TE makes |E| > |U1|;

therefore, |F| < 1 and the feedback at this frequency is positive. In cases (c) and (d), |E| < |U1|, and

the feedback at this frequency is negative.

Replacing the Laplace variable s by jω in a Laplace transfer function, where ω is understood to be the frequency in rad/s, results in the frequency-dependent transfer function.

The transfer function is the ratio of the signals at the link’s output and input, which depend

on the frequency.

Plots of the gain and phase of a transfer function vs. frequency are referred to generically as the frequency response.

The loop frequency response is defined by the complex function T(jω). The magnitude

|T(jω)| expressed in decibels (dB) is referred to as the loop gain. The angle of T(jω) is the

loop phase shift, which is usually expressed in degrees. Plots of the gain (and sometimes

the phase) of the loop transfer function with logarithmic frequency scale are often called

Bode diagrams, in honor of Hendrik W. Bode, who, although he did not invent the diagrams,

did develop an improved methodology of using them for feedback system design, to be

explained in detail in Chapters 3 and 4. The plots can be drawn using angular frequency

ω or f = ω/(2π) in Hz.

Example 1.12

Let

T (s ) =

num

5, 000

5, 000

=

=

den s( s + 5)( s + 50) s 3 + 55s 2 + 250s + 0

where num and den are the numerator and denominator polynomials.

8

Classical Feedback Control: With MATLAB® and Simulink®

Gain dB

50

0

–50

10–1

100

101

Frequency (rad/sec)

102

100

101

Frequency (rad/sec)

102

Phase deg

0

–90

–180

–270

10–1

FIGURE 1.7

MATLAB plots of gain and phase loop responses.

The frequency responses for the loop gain in dB, 20 log|T(jω)|, and the loop phase shift

in degrees, (180/π) arg T(jω), can be plotted over the 0.1 to 100 rad/s range with the software

package MATLAB® from Mathworks, Inc. by the following script:

w = logspace(–1, 2);

% log scale of angular

% frequency w

num = 5000;

den = [1 55 250 0];

bode(num, den, w)

The plots are shown in Figure 1.7. The loop gain rapidly decreases with frequency, and

the slope of the gain response gets even steeper at higher frequencies; this is typical for

practical control systems.

The loop gain is 0 dB at 9 rad/s, i.e., at 9/(2π) ≈ 1.4 Hz. The phase shift gradually changes

from – 90° toward – 270°, i.e., the phase lag increases from 90° to 270°.

MATLAB function conv can be used to multiply the polynomials s, (s + 5), and (s + 50)

in the denominator:

a = [1 0]; b = [1 5]; c = [1 50];

ab = conv(a,b); den = conv(ab,c)

More information about the MATLAB functions used above can be obtained by typing

help bode, help logspace, and help conv in the MATLAB working window, and from the

MATLAB manual. Conversions from one to another form of a rational function can be also

done using MATLAB functions tf2zp (transfer function to zero-pole form) and zp2tf (zeropole form to transfer function).

9

Feedback and Sensitivity

Gain, dB

|T|

0

|F|

Large feedback, |F|>>1

Negative feedback,

|F|>1

|M|

f, log. scale

fb

Positive

feedback,

|F|<1

Negligible

feedback,

|F|≈1

FIGURE 1.8

Typical frequency responses for T, F, and M.

Example 1.13

The return ratio from Example 1.12, explicitly expressed as a function of jω, is

T ( jω ) =

5, 000

jω( jω + 5)( jω + 50 )

At frequency ω = 2, T ≈ 10∠–110°, and F ≈ 9∠–115o, so the feedback is negative. |T| reduces with

frequency. At frequency ω = 9, T ≈ 1∠–160°, and F ≈ 0.2∠–70°, so the feedback is positive.

The Bode plot of |T| for a typical tracking system is shown in Figure 1.8 by the solid line.

The loop gain decreases with increasing frequency. The diagram crosses the 0 dB line at

the crossover frequency f b where, by definition, |T(f b)| = 1.

The frequency response of the feedback |F| is shown by the dashed line. It can be seen

that the feedback is negative (i.e., 20 log|F | > 0) up to a certain frequency, becomes positive

in the neighborhood of f b, and then becomes negligible at higher frequencies, where F → 1

and 20 log|F | → 0.

The input-output closed-loop system response is shown by the dotted line. The gain is

0 dB (i.e., the gain coefficient is 1) over the entire bandwidth of large feedback. The hump

near the crossover frequency is a result of the positive feedback. This hump, as will be

demonstrated in Chapter 3, results in an oscillatory closed-loop transient response, and

should therefore be bounded.

In general, feedback improves the tracking system’s accuracy for commands whose dominant Fourier components belong to the area of negative feedback, but degrades the system’s accuracy for commands whose frequency content is in the area of positive feedback.

1.4.2 Nyquist Diagram

To visualize the transition from negative to positive feedback, it is helpful to look at the

plot of T on the T-plane as the frequency varies from 0 to ∞. This plot is referred to as the

Nyquist diagram and is shown in Figure 1.9. Either Cartesian (ReT, ImT) or polar coordinates (|T| and arg T) can be used.

10

Classical Feedback Control: With MATLAB® and Simulink®

Im T

T-plane

T-plane

–1

1

f

f1

Re T

F

T

0

±180°

0°

fb

(a)

(b)

FIGURE 1.9

Nyquist diagram with (a) Cartesian and (b) polar coordinates; the feedback is negative at frequencies up to f 1.

The Nyquist diagram is a major tool in feedback system design and will be discussed in

detail in Chapter 3. Here, we use the diagram only to show the locations of the frequency

bands of negative and positive feedback in typical control systems.

At each frequency, the distance to the diagram from the origin is |T|, and the distance

from the –1 point is |F|. It can be seen that |F| becomes less than 1 at higher frequencies,

which means the feedback is positive there.

The Nyquist diagram should not pass excessively close to the critical point –1 or else the

closed-loop gain at this frequency will be unacceptably large.

In practice, Nyquist diagrams are commonly plotted on the logarithmic L‑plane with

rectangular coordinate axes for the phase and the gain of T, as shown in Figure 1.10a.

Notice that the critical point –1 of the T-plane maps to point (–180°, 0 dB) of the L‑plane. The

Nyquist diagram should avoid this point by a certain margin.

Example 1.14

Figure 1.10b shows the L-plane Nyquist diagram for T = (20s +10)/(s4 + 10s3 +20s2 + s) charted with

MATLAB script:

num = [20 10]; den = [1 10 20 1 0];

[mag, phase] = bode(num, den);

plot(phase, 20*log10(mag), ‘r’, –180, 0, ‘wo’)

title(‘L-plane Nyquist diagram’)

set(gca,’XTick’,[–270 –240 –210 –180 –150 –120 –90])

grid

It is recommended for the reader to run this program for modified transfer functions and to observe

the effects of the polynomial coefficient variations on the shape of the Nyquist diagram.

1.4.3 Nichols Chart

The Nichols chart is an L-plane template for the mapping from T to M, according to

Equation 1.5, and is shown in Figure 1.11. When the Nyquist diagram for T is drawn on

this template, the curves indicate the tracking system gain: 20 log |M|.

It is seen that the closer the Nyquist diagram approaches the critical point (–180°, 0 dB), the

larger |M| is, and therefore the higher is the peak of the closed-loop frequency response

in Figure 1.8. The limiting case has |M| approaching infinity, indicating that the system

11

Feedback and Sensitivity

L-plane Nyquist Diagram

100

Gain, dB

L-plane

f

50

Phase, degr

0 dB

–180°

0

fb

–50

–100

–270 –240 –210 –180 –150 –120 –90

(b)

(a)

FIGURE 1.10

Nyquist diagrams on the L-plane, (a) typical for a well-designed system and (b) MATLAB generated for

Example 1.14.

20

dB

15

15

10

10

5

6 dB

8 dB

10 dB

4 dB

3 dB

1 dB

2 dB

5

0B

–1 dB

0

–2 dB

–5

–4 dB

–5

0

–6 dB

–10

–15

–15

–20

–10

–10 dB

–15 dB

0°

10°

20°

30°

40°

50°

60°

Deviation in Phase from –180°

FIGURE 1.11

Nichols chart.

70°

80°

–20

90°

12

Classical Feedback Control: With MATLAB® and Simulink®

goes unstable. Typically, |M| is allowed to increase not more than two times, i.e., not to

exceed 6 dB.

Therefore, the Nyquist diagram should not penetrate into the area bounded by the line

marked 6 dB.

Consider several examples that make use of the Nichols chart.

Example 1.15

The loop gain is 15 dB, the loop phase shift is –150°. From the Nichols chart, the closed-loop gain

is 14 dB. The feedback is 15 – 1.4 = 13.6 dB. The feedback is negative.

Example 1.16

The loop gain is 1 dB, the loop phase shift is –150°. From the Nichols chart, the closed-loop gain

is 6 dB. The feedback is 1 – 6 = – 5 dB. The feedback is positive.

Example 1.17

The loop gain is –10 dB, the loop phase shift is –170°. From the Nichols chart, the closed-loop gain

is –7 dB. The feedback is –10 – (–7) = –3 dB. The feedback is positive.

1.5 Disturbance Rejection

Disturbances are signals that enter the feedback system at the input or output of the plant or

actuator, as shown in the Simulink diagram in Figure 1.12, and cause undesirable signals at

the system output. In the antenna pointing control system, disturbances might be due to wind,

gravity, temperature changes, and imperfections in the motor, the gearing, and the driver. The

disturbances can be characterized either by their time history or, in frequency domain, by the

Fourier transform of this time history, which gives the disturbance spectral density.

The frequency response of the effect of a disturbance at the system’s output can be calculated in the same way that the output frequency response to a command is calculated: it is

the open-loop effect (D1 AP, for example) divided by the return difference F.

In Figure 1.12, three disturbance sources are shown. Since in linear systems the combined effect at the output of several different input signals is the sum of the effects of each

separate signal, the disturbances produce the output effect

D1

Command

+

C

–

FIGURE 1.12

Disturbance sources in a feedback system.

+

D2

A

B

D3

+

P

+

Output

13

Feedback and Sensitivity

D1 AP + D2 P + D3

F

The effects of the disturbances on the output are reduced when the feedback is negative

and increased when the feedback is positive. Disturbance rejection is the major purpose

for using negative feedback in most control systems.

There exist systems where there is no command at all, and the disturbance rejection is

the only purpose of introducing feedback. Such systems are called homing systems. A

typical example is a homing missile, which is designed to follow the target. No explicit

command is given to the missile. Rather, the missile receives only an error signal, which

is the deviation from the target. The feedback causes the vehicle’s aerodynamic surfaces to

reduce the error. This error can be considered a disturbance, and large feedback reduces

the error effectively. Another popular type of a system without an explicit command is the

active suspension, which uses motors or solenoids to attenuate the vibration propagating

from the base to the payload.

Example 1.18

The feedback in a temperature control loop of a chamber is 100. Without feedback, when the

temperature outside the chamber changes, the temperature within the chamber changes by 6°.