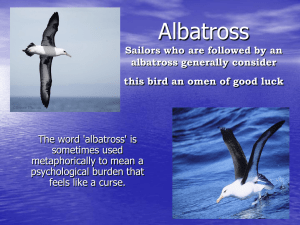

47 MOTIF OF DEATH AND REBIRTH A frequently recurring motif in Coleridge’s poetic world relates to death and rebirth. Death does not mean only physical death and transmigration of soul into another body but it symbolises sufferings or death-in-life; isolation and loneliness and spiritual vacuum and awareness of it is rebirth. “The Rime of The Ancient Mariner” is exquisitely woven around the theme of death and rebirth. Death and rebirth in Coleridge’s poetry also symbolise the ebb and flow of poetic inspiration. In “The Rime of The Ancient Mariner,” Coleridge’s creative imagination has fused all the elements of drama, narrative and verse into a unified whole. The voyage in “The Rime of The Ancient Mariner” is an archetype of the spiritual journey which all men experience. The Mariner is an archetype of the man who annoys God. “The poem can be analysed in terms of the Jungian collective unconsciousness and the patterns of death and rebirth to those recurring in anthropological studies of comparative religion.” (Adair 17) George Whalley has pointed out the allegorical motive of the poem: “The Rime of The Ancient Mariner” is less of a fantastical imagination and a drowsie dream than a “continued allegory and a dark conceit.” (Adair 164) The allegorical motive and the subjective content which Coleridge infused into the poem consciously or unconsciously is also confirmed by an important letter of Coleridge: I have often thought, within the last five or six years, that if ever I should feel once again the genial warmth and stir of the poetic impulse and referred to my own experience, I should venture on a yet stronger and wider allegory. . . than I would allegorise myself, as a rock with its summit just raised above the surface of some bay or straight in the Arctic Sea. (Bennet 85) 48 Coleridge starts the poem on a realistic note to attain that “willing suspension of disbelief” which was the essential tenet of his poetics. The bright-eyed Mariner stops a wedding guest and narrates his tale of woe. He listens to him like a “three year child” (15). The narrative relates to the voyage of the ship through the tortuous sea. In an entry of December 1803, Coleridge uses the imagery of the sea and ship to describe the subconscious world of sleep and dreams: O then as I first sink on the pillow, as if sleep had indeed a material realm. . . O then what visions have I had, what, dreams the bark, the sea all the shapes and sounds and adventures made up of the Stuff of sleep and dreams, & yet my reason at the rudder. . . I sink down the waters, thro` Seas & Seas Yet warm, yet a Spirit. (Adair 84) The above citation confirms that so many years before Freud, Coleridge was aware of the world below the surface of the sea, the subconscious, the abode of dreams. He added the beautiful gloss on the moving moon to “The Ancient Mariner” in 1817 which reveals his own feeling: In his loneliness and fixedness he yearnth towards the Moon, and the stars that still sojourn, yet still move onward; and everywhere the blue sky belongs to them, and is their appointed rest, and their native country and their own natural homes, which they enter unannounced, as lords that are certainly expected and yet there is a silent joy at their arrival. (Coleridge, E.H. 197) Coleridge had often watched the sky and knew the movement of moon and stars. The gloss expresses not only his personal loneliness but a deeper philosophical awareness of man’s place in the cosmos. The moon and stars pursue their appointed paths in the heavens according to the unalterable laws of the natural world. Man only is left outside, an eternal wanderer in a universe where he has no assured place. Like the Mariner, he is the ‘outcast of a blind idiot called Nature,’ (Griggs 177) though the 49 beauty of the gloss shows that Coleridge has performed the poet’s task of endowing the ‘inanimate cold world’ with imaginative life. The terrifying isolation of the ancient Mariner is, to some extent, the predicament of modern man. In an another entry made in Malta, which also describes the moon, sees it this time as an image of that inner world which Coleridge knew very well: In looking at objects of Nature while I am thinking, as at yonder moon dim-glimmering thro` the dewy window pane, I seem rather to be seeking, as it were asking, a symbolical Language for something within me that already and forever exists, than observing anything new. (Coburn 104) Viewed from the Jungian perspective, Coleridge’s assertion is of paramount importance. As Jung holds, water is the commonest symbol of the unconscious and the lake in the valley is the unconscious. “The harbour cleared” (21), the ship sets sail. The line harbour cleared signifies that all the impediments in the flow of the poetic inspiration are removed and it flows spontaneously. The ship sails smoothly ‘below the kirk, below the hill’ (23) and “the light house top.” (24) The sun comes out on the left and after shinning brightly, goes down into the sea on the right with clock-like precision. The rising and setting of the sun represent the archetype of rebirth. “The ark, chest, barrel, ship etc. is an analogy of the womb, like the sea into which the sun sinks for rebirth.” (Jung Symbols of Transformation 11) The wedding guest hears “the loud bassson” (32). He is hypnotised by the bright-eyed Mariner, for “he cannot choose but hear” (37): The bride hath paced into the hall, Red as a rose is she, Nodding their heads before he goes The merry minstrelsy. . . (33-36) The merry atmosphere of the stanza indicates the poet’s cheerfulness at the uninterrupted flow of the inspiration, which fades in the next stanza. The archetype of the anima is exhibited here. The anima-image is usually projected upon women. Due to lesser number of feminine genes, the feminine character leads a subordinate life. In 50 the realm of the archetype of anima, the ship’s voyage enters into a strange phase and the topography of the region undergoes a drastic change. The smooth sailing and calm and serene atmosphere are replaced by a storm which roars full blast. The ship is driven at a tremendous pace along the tumultuous tide. The expression is a pointer to the overwhelming flow of the poetic inspiration. Under the gust of the storm, the ship proceeds with “sloping masts and dipping prow”(44) and advances with “yell and blow”(46). In the realm of the archetype of the shadow, the geography of the region shows a marked change. It marks its entry into the region of mist and snow. This is the first indication of the withering of the poetic flow and the topography is replaced by a “dismal sheen” (56), where ice “cracked and growled” (61). From the horizon approaches the albatross, making its way through the thick fog. The mist of the preceding stanza is replaced by the denser medium of the fog. At length did cross an albatross, Through the fog it came, As if it had been a Christian soul, We hailed it in God’s name. (63-66) The albatross is an important symbol and is endowed with deep personal significance. George Whalley gives an extended significance to the albatross: The albatross… binds inseparably together the three structure principle of the poem: the voyage, the supernatural machinery and the unfolding cycle of the deeds results. Nothing less than an intensely personal symbolism would be acceptable against the background of such intense suffering. The albatross must be much more than a stage property chosen at random or a mechanical device introduced as motive of action in the plot. The albatross is the symbol of Coleridge’s imagination, the eagle. (Whalley 178) The link between the albatross and the creative imagination grows out of the inner necessity of the poem and can be verified: 51 I had killed the bird That made the breeze to blow. (93-94) With the advent of the albatross, a favourable wind fans the ship. Coleridge associates Genius with the wind. Coleridge likens the wind to the creative wind, for which he always longed: Whither have an Animal Spirits departed? My hopes-O me! That they which once had to check… should now be an effort/ Royals & Studding Sails & the whole canvas stretched to catch the feeble breeze! I have many thoughts, many images, large store of unwrought materials… but the combining Power, the power to do, the mainly effective Will, that is dead or slumbers most diseasedly. (Adair 83) The entry suggests that there are moments in “The Ancient Mariner” when the rising wind is identified with imaginative power and its dropping with stagnation. The symbol of imagination, or of inspiration, is frequently a bird in several of Coleridge’s writings. The records of the years show us Coleridge’s deepening loneliness, the bitterness that crept into his relations with Sara Hutchinson, his estrangement from Wordsworth and with it, Sara’s division from him, the discord of his marriage and the resulting loss of his children. Increasing ill-health and slavery to opium and what seemed the death of his creative power, all created a vicious circle of self-pity and self-disgust, a weariness of life. His bitter knowledge of Life-in-Death could be proved from the following entries: -O me! My very heart dies!- This year has been one painful Dream/I have done nothing! – O for God’s sake let me whip & spur, so that Christmas may not pass without something having been done/… the Rain Storm pelts against my Study Window! why am I not happy! Why have I not an unencumbered heart!... (Coburn 297) The second entry belongs to 1807 shortly after the ‘dreadful Saturday Morning’ when some incident ocurred which aroused Coleridge’s intense jealousy of Wordsworth and 52 Sara. The image of the ‘nightmare’ suggests Life-in-Death, and it is possible both were written about the same time: For whenever I seem to be slighted by you, I think not what I am not to you, but only what I have claim to be-& then I sink -& but that it is a dream, & I still half-consciously expect to awake from the night-mair- I could not but die- die,/as an act! – O! Sara! (Coburn 67) The stress upon ‘die as an act’ seems to mean suicide as opposed to ‘the night-mare Life-in-Death’. In the entry of February 1807, Coleridge uses the image of soul’s wings, which without Sara can no longer soar: O God! Forgive me; can even the Eagle soar without wings? And the wings given by thee to my soul- what are they, but the Love & society of that Beloved…(Adair 86) Along with the breeze, the albatross is the symbol his imaginative power. In the Jungian terms, “it can be called the archetype of the trickster, a figure, which sets in motion a chain of events.”(Jung The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious 23) It entices the Mariner to commit the grave act. As a result, the crew and the ship undergo dreadful consequences. The Mariner falls victim to the machinations of the trickster figure that compels him to commit the wanton act. The trickster figure is the product of the unconscious. As Jung says: A curious combination of trickster motifs can be found in the alchemical figures of Marcurius. For instance his fondness for sly jokes and malicious pranks, his power as a shape shifter, his dual nature, half animal, half divine, his exposure to all kinds of tortures, and last but not least-his approximation to the figure of a Saviour.(Jung Four Archetypes 135) The trickster figure is hailed by the crew because of its saving quality and is referred to as “a Christian Soul” (65). Like all the archetypes, it has a dual nature, that becomes apparent after a short span. Recalling the phantom of the trickster, Jung holds that he is obviously “a psychologem”, an archetype of extreme antiquity. The 53 trickster is a collective shadow figure. It can construct itself continually, and the most alarming characteristic is his unconscious. The coming of the albatross heralds a favourable turn, the ice splits and the ship is steered through. Day after day, the albatross follows the ship: In mist or cloud, on mast or shroud, It perched for vespers nine; Whiles all the night, through fog-smoke white. (75-77) The reference to the shroud signifies the gloomy forebodings ahead. The night or darkness is a sign of the unconscious, which like fog engulfs the bright sunny day. A good south wind springs and the ship is steered through the glimmering moonlit night. The appearance of the moon, the symbol of the mother archetype, and the moving of the ship highlight the redemptive features, though the fog and the mist are also there. The trickster’s dual nature comes to the fore, when the Mariner shoots the albatross. With my cross bow I shot the albatross. (81-82) The shooting of the albatross has led to many and various symbolic interpretations by Coleridge’s critics. Mr. Penn Warren, one of the most influential and penetrating of the symbolist critics, thinks the death of the albatross represents the Fall of Man, a crime against the sacramental vision of the ‘One Life’ which Coleridge had expressed in “Eolian Harp”: O! the one Life within us and abroad, . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . Methinks, it should have been impossible Not to love all things in a world so fill’d. (Coleridge, E. H. 101) Professor G. Wilson Knight thinks the slaying of the albatross may correspond to the death of Christ in racial history. (Knight 85) The crime is wanton and unintentional. The Mariner shoots the albatross, “the pious bird of good omen” (Whalley 175) without taking into consideration the implication of his deeds. Like the Mariner’s wanton act, Coleridge also fell victim to the charms of opium. Prescription of opium is used to relieve pain, but addiction to it proves detrimental to health. Inadvertently 54 Coleridge fell victim to the charms of opium, and slavery to it proved to be an impediment, playing havoc with his creative power, that created a weariness of life: O had I health and youth, and were that I once was-but I played the fool the throat of my Happiness, of my Genius, my utility, in complaint to the nearest phantom of overstrained Honor. (Whalley 175) Unwittingly the Mariner shoots the albatross. The act is fortuitous and Coleridge is not aware of the process when he started killing his eagle. The stark tragedy of Coleridge’s life and the Mariner’s voyage is based on the knowledge of this concept that the act could have been avoided. The brief period of the moon alternates with the sun that rises from the right and is immersed into the sea without shining brightly. Obviously the reference is to the archetype of rebirth, “night sea journey” stressing the maternal significance of water, Jung states: The maternal significance of water is one of the clearest interpretation of symbols in the whole field of mythology, so that even the ancient Greeks could say that ‘the sea is the symbol of generation.’ (Jung Four Archetypes 142) The chest, barrel, ship etc. symbolise the womb. “The sun sails over the sea like an immortal, who, every evening, is immersed in the maternal waters and is born anew in the morning.” (Jung Symbols of Tranformation 218) Illustrating the maternal significance of water, Jung states that even in the Vedas, the water is called “matriamah,” most maternal. All living things rise like sun from the water and sink into it again at evening. The malicious trick of the archetype of the trickster foxes him and he thinks it better to slay a bird that brings mist and snow. The fair breeze is like a mirage in a desert as it steers them into “the silent sea” (106). On account of it: Down dropt the breeze, the sails dropt down, `t was sad as sad could be; And we did speak only to break 55 The silence of the sea! (107-110) The blistering heat of the bloody sun becomes unbearable and it stands still upon the mast “no bigger than moon” (114). Implying terror, the bloody sun signifies the red colour. The stanza forms the central core of the poem. Probably it implies the failure of the poetic inspiration. The breeze dwindles, the sails become flabby and it is as “sad as could be” (107. The sun and the moon change with the geography of the voyage and also with the Mariner’s spiritual state; they cannot be rigidly limited in meaning. The terrible calm and the rotting sea do seem to suggest the stagnation and corruption of the soul, a waste land of the spirit, but not because the natural world has turned against the Mariner. Rather it has become an image of the loneliness and fear the guilty soul feels. The loneliness and gloominess are imparted by the symbol of the wasteland amidst the sea: Water, water, everywhere, And all the boards did shrink; Water, water, everywhere, Ne any drop to drink. (21-24) Water, the old Christian symbol of life, has become death for the Ancient Mariner. The wasteland is a pointer to the barrenness of Coleridge’s mind, from where does not erupt even a single shoot of poetry. In the next verse he calls on Christ: The very deeps did rot: O Christ! That ever this should be! Yea, slimy things did crawl with legs Upon the slimy sea. (120-123) The line “the very deep did rot: O Christ” (123) points to the rot in Coleridge’s mind. Christ is the symbol of the unconscious, the Saviour. The God-image is an archetype, which comes to the threshold of the conscious when man is in distress. The rot of the sea is stemmed and it becomes inhabited by the slimy creatures. They contain the germ of the future, connoting little chance of revival. Describing the concept of Progression and Regression, Jung says: Progression is the daily advance of the process of psychology adaptation, which at certain times, fails. The 56 ‘vital feeling’ disappears, there is damming up of energy of libido. At such times, in the patients he has studied, neurotic symptoms are observed, and repressed contents appear, of inferior and unadapted character. ‘Slime out of the depths’ he calls such contents using the symbolism We have just been studying but slime that contains not only objectionable animals tendencies, but also germs of new possibilities of life. (Bodkin 52) Before renewal of life can take place, Jung urges that “there must be an acceptance of the possibilities that lie in the unconscious contents activated through regression… and disfigured by slime of the deep.” (Jung Four Archetypes 101) The confused thoughts emerge from the slime and he sees: The death fires danced at night; The water like a witch’s oils. (128-29) The ship mates are not able to utter a single word because of the parched condition. However, they are casting evil looks at the culprit, who is responsible for gross misconduct. Part II ends with the terrible thirst and the amazingly vivid and concrete image: We could not speak no more than if We had been choked with soot. (137-38) Once again the awareness of the sin is conveyed not through natural image but by the great Christian symbol: Ah wel-a-day! What evil looks Had I from old and young; Instead of the cross the Albatross About my neck was hung. (139-42) Part III opens with the allusion to the weary time and is oft repeated in the later lines. “A weary time” (145) signifies the poet’s tiring attempts to regain the poetic inspiration. The later stanza ushers an era of hope because the Mariner sees a little speck coming out of the mist. The impression of thirst, surprise and elation is conveyed aptly by the lines: 57 I bit my arm, I sucked the blood And cried, A sail; a sail (160-61) The approaching ship “plunged, tacked and veered” (156) as if it dodged a water spirit (155). Spirit is an archetype of extreme antiquity and has its abode in the unconscious. As Jung says: The psychic manifestations of the spirit indicate that they are of an archetypal nature, in other words, the phenomenon we call spirit depends on the existence of an autonomous primordial image which is universally present in the preconscious make up of the human psyche. (Bodkin 53) The emergence of the saviour ship turns out to be the machination of the trickster figure. The renovation of the same can be explained by the fact that the figure does not vanish easily. It seeks a suitable opportunity to reappear. Owing to the loss of energy, it has merely withdrawn into the unconscious, where it remains so long as the conscious is in a perfect situation. The re-emergence of the archetype is explained by Jung: But if the conscious should find itself in a critical or doubtful situation that it becomes apparent that the shadow has not dissolved into nothing but is only waiting for a favourable opportunity to reappear as a projection upon one’s neighbour. If this trick is successful, there is immediately created between him that the world of primordial darkness where everything that is characteristic of the trickster can happen. (Jung Symbols of Transformation 223) The strange ship drives suddenly between them and the sun and exhibits queer qualities: And straight the Sun was flecked with bars, (Heaven’s Mother send us grace! As if through a dungeon grate he peered 58 With broad and burning face. (177-80) The natural world is imprisoned by the supernatural and in the next verse, the beautiful natural image of ‘gossamers’ is used to convey the transparency of the skeleton ship’s sails: Are those her Sails that glance in the Sun Like restless gossamers? (183-84) The sails appear like “restless gossamers” (184). The grace of Heaven’s Mother is invoked to protect them from calamity and misfortune in the offing. God is an archetype and has an abode in the unconscious. The symbol of dungeon grate acquires weight because it suggests the trapped poetic power. Even in “Kubla Khan” the river of imagination flows from beneath the caverns and catacombs. Death and her mate life-in-death are the two inhabitants of the ship. Death is, psychologically speaking, a phenomenon of paramount importance. As Jung puts it: The neurotic medical psychologists tell us death is envisaged not objectively as normal people are expected to view it as the end of life, an event with social, moral and legal implications but as ‘a quiescent equilibrium’ realised once (it is supposed) at the beginning of life, within the mother’s womb. Within the poetic vision, however, the craving for death is not a mere crude impulse. It is an impulse actively realising itself anew in the conscious with other tendencies attaining a new character in synthesis.” (Bodkin 66) The description of death and her mate projects the archetype of the anima. The struggle ensues between death and life-in-death for the possession of the Mariner’s soul. Though the struggle is not described in detail, yet the game of dice indicates that life-in-death wins the process. Commenting on the possessive nature of the anima, Jung states: The anima is fickle, capricious, moody, uncontrollable and emotional, sometimes gifted with daemonic 59 intuitions ruthless, malicious, untruthful, bitchly, double-faced, and mystical. (Bodkin 66) Life-in-death is a recurrent theme in Coleridge’s thought. In the “The Ancient Mariner,” it is personified: Her lips were red, her looks were free, Her locks were yellow as gold, Her skin was as white as leprosy, The Night-mare Life-in-death was she, Who thicks man’s blood with cold. (190-194) It is for Coleridge a mixture of endless suffering, remorse, loneliness and terror. Life-in-death ebbs the little traces of revival and fills the poet’s heart with fear, where “life blood seemed to sip” (205). It brings forth an era of night and darkness, which are detrimental to the interest of the poet. As Jung states in his theory of rebirth: The darkness which clings to every personality is the door into the unconscious and the gateway of dreams, from which these two twilight figures, the shadow and the anima, step into our nightly visions or remaining invisible take possession of our ego-consciousness. (Jung The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious 144) With the departure of the Spectre-ship the horned moon rises and by its light, the sailors drop dead one by one. The horror of his comrades’ deaths is brought out by dead sounds, ‘with heavy thump, a lifeless lump’. The night marks “the advent of the horned moon” (210) and “every mate cursed me with his eyes” (215). This reminds us of the diseased condition of the moon in “Christabel.” The moon is usually associated with the mother archetype, but its dilated condition can be linked to the negative effect of the mother archetype. In Coleridge’s writings the waning moon is a bad omen. A disasterous occurrence makes its appearance. All the ship mates fall victim to the cruel hands of death and their soul dart towards the sky like “the whiz of his bow” (223). 60 Part IV is fraught with the sense of isolation and loneliness of the Mariner. The pangs of loneliness crop up again and again: Alone, alone, all, all, alone, Alone on a wide wide sea! And never a saint took pity on My soul in agony. (232-235) In recalling this part of his penance in his closing words to the wedding-guest, the Mariner says: O Wedding-Guest! this soul hath been Alone on a wide wide sea; So lonely `t was, that God himself Scarce seemed there to be. (597-600) What is so striking about this part of the poem is that the Mariner sins by hating himself and the ‘thousand thousand slimy things’ that he sees; but his heart is ‘as dry as dust’, so he can hardly be capable of either love or prayer. His state is like that of Cain, whom god punished by ‘drying up’ his heart: and Cain is trapped in a barren selfhood, and also desires death, or oblivion, the negation of self. “O that I might be utterly no more! I desire to die – yea, the things that never had life, neither move they upon the earth – behold! They seem precious to mine eyes. . . the Mighty One who is against me speaketh in the wind of the cedar grove; and in the silence am I dried up.” (Coleridge, E.H 288) This is the state of Life-in-Death, which is so much more horrible than death itself that death is longed for and sought out as a blessed release. But its changelessness, or ‘fixedness’ as Coleridge later says, and the complete paralysis of the will which it inflicts on the victim, can be broken only by an act of grace. His loneliness is quelled by a “thousand slimy things” (239), visible from the rotting deck in the rotting sea. The symbols of decay are enshrined in the image of the rotting sea where only slimy things live, and the rotting deck where litter dead bodies. He is burdened by the grave sin and it lies like “a load on my weary eyes” (251). The haunting looks on the eyes of his dead mates make him conscious of his guilt. Inspite of frequent attempts, the rebirth eludes him. 61 The moon rises and sheds its horned character. The moon beams seem to be mocking “the sultry main” (267) and the shadow of the ship is cast on the terror stricken sea, whose colour is “awful red” (271). In the realm of the archetype of the shadow, everything is unconditional and events take an unsuspecting trend. As Jung states: A man who is possessed by the shadow is always standing in his own light and falling into his own traps. In the long run luck is always against him because he is living below his own level and at best only attains what does not suit him. (Whalley 163) In the shadow of the ship, the water snakes “coiled and swam” (280) with their rich attire. The gentle rhythm of the moon’s smooth ascent creates in this context an extraordinary feeling of release. Her remote beauty has no part in the terrible sea over which she shines, yet she is a reminder of the unalterable laws of the natural world and in this universe of death, even that is a consolation. In the light of the moon, the Mariner becomes aware of the shining beauty and the graceful movement of the water snake. No sooner does the impulse of love erupt towards the slimy, elfish water snakes than the redemption of the poetic inspiration takes place. The Mariner is able to pray again, for “a kind saint took pity” (286) on him and the burden is lightened. As the renewed reconciliation with the living world takes place: The Albatross fell off, and sank Like lead into the sea. (290-291) This marks a turning point in the poem and could be taken as the beginning of Christian redemption or as renewed reconciliation with the living world he had outraged. Mr. Warren thinks it a mixture of the two and, in the working of the ship by the dead men, sees an image ‘of regeneration and resurrection.’ (Warren 97) Part V opens on a gentle note with the healing sleep and rain which refresh the Mariner’s weary soul and body. Wind and storm arise and, under the lightning, the dead men begin to work the ship. The Mariner showers praise upon Mary Queen, the Mother, who relieves him of his torture and sends him to gentle sleep, which “slid 62 into his soul” (296). Sleep is welcomed because Coleridge associates sleep with the feeling up of his creative activity. In 1801, he gives an account of his views: The sleep which I have is made up of ideas so connected, & so little different from the operations of the reason, that it does afford me the due refreshment for it seemed to me a suicide of my very soul to divert my attention from Truths so important which came to me almost as a Revelation. (Jung The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious 123) During the soothing sleep, he dreams of empty buckets filled with life sustaining dew. As he awakens from the trance-like state, it begins to rain. The source of the dream is collective unconscious, which is continually active, combining its material in ways which serve the future. In other words, dreams have the power of prediction: A very large number of accidents of every description, more than people would ever guess are of psychic causation, ranging from trivial mishaps like stumbling, banging oneself etc-all those may be psychically caused and may sometimes have been preparing for weeks or even months. I have examined cases of this kind, and often I could point to dreams which show signs of a tendency to self injury weeks before hand. (Adair 88) The parched condition vanishes and the weary burden diminishes. Soon he hears roaring wind and its sound seems to set in motion the flaccid sails and the ship surges ahead. The roaring wind is the fuel of his creative inspiration, for which he has longed. Due to the favourable breeze, “the upper air burst into life” (313), the still atmosphere is dispelled and the state of inactivity is replaced by activity: To and fro they were hurried about! And to and fro, and in and out, The wan stars danced between. (315-317) 63 The stanza refers to the process of association and disassociation of images in the subconscious or it refers to the alternate ebbing and swelling of the creative inspiration. The state of thirst is quenched as “the rain poured down from one cloud” (320). The one black cloud does not hide or eclipse the bright moon. “Water shot from some high crag” (324) can be analogous to the eruption of the fountain in “Kubla Khan.” The unconscious resumes its activity and the process of association of images sets in. As a result, “a river steep and wide” (326) begins to flow. In many of his notebooks, Coleridge dwells on the symbol of the river or stream to suggest poetic process. In an entry of December1803, he writes: I will at least make the attempt to explain to myself the origin of moral Evil from the streamy Nature of Association, which Thinking=Reason, curbs & rudders/ how this comes to be so difficult/ Do not the bad passion in Dreams throw light & shew of proof upon this Hypothesis. (Jung The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious 124) The wind never reaches the ship, still the sails stir and the ship sails swiftly in the light of the moon. The dead men stir and begin working as a crew. It suggests the magical quality of the creative inspiration, just as the pleasure dome of “Kubla Khan” can be constructed by the poet’s creative ability. Nature takes a favourable turn, the skylark sings and the little birds fill the sea with their “sweet jargoning” (362). And now `t was like all instruments, Now like a lonely flute; And not it is an angel’s song That makes the heavens be mute. (363-66) The cheerful state continues till noon. The pleasant noise resembles the noise of a hidden brook “in the leafy month of June” (370). The serene, dreamy movement of the sea suggests the ease and harmony of the creative inspiration before it disappears into oblivion. At noon the sails left off their tune (381) and the ship comes to a stand still. The sun is high up in the sky, the scorching heat affects the Mariner and he “fell down 64 in a swound” (392). The poetic inspiration again fades, the Mariner grieves intensely for that loss and goes into a fit. Recovering partially from the fit, he discerns two voices in the air, holding a dialogue with each other. The lengthy debate is focused on the deed of the Mariner and his penance. The emergence of the voices and their parley can be interpreted in terms of the following Jungian citation: The voice is a frequent occurrence in the dream. It always utters an authoritative declaration or command, either of astonishing common sense or of profound philosophical import. It is nearly always a final statement usually coming towards the end of the dream, and it is, as a rule, so clear and convincing that the dreamer finds no argument against it. (Adair 118) The voice is an important and decisive spokesman of the unconscious. The result of the declaration of the voices is, “the man hath penance done and penance more will do” (409), and it is also the final fate of the Mariner. The point of discussion between the two voices is the force which drives the ship “without a wave or sound” (423). When the Mariner’s senses are fully activated, he finds the ship’s progress unhampered, but he is still apprehensive of its progress. The fear is expressed in the stanza: Like one that on a lonesome road Doth walk in fear and dread, And having once turned round walk on, Because he knows, a frightful friend Doth close behind him tread. (446-50) It epitomises Coleridge’s fear that his poetic activity is in a state of decline. The fear is imaginary because: Soon there breathed a wind on me, Nor sound nor motion made… (451-452) The period of stagnation is over and the ship goes along its course. Though the effect of the breeze is not visible, yet “on me alone it blew” (463). The lines “doth walk in fear and dread” (447) summarises the tragedy of Coleridge’s life and that of 65 the Mariner. The breeze fans his cheek and raise his hair like the gust of spring. Still fear lurks in the heart that the breeze may be suspended again. The line “it mingled strangely with my fears” (458) is fraught with the meaning of the same magnitude and signifies the apprehensive fear. The alternate periods of the ebbing and swelling, the retardation and acceleration of the poetic activity correspond with the Jungian concept of the archetype of rebirth. Rebirth is an affirmation that must be counted among the primordial affirmation of mankind. These primordial affirmations are based on what Jung calls archetype: This word has a special flavour, its whole atmosphere suggests the idea of renovation, renewal or even of improvement brought about by magical means. Rebirth may be a renewal without any change of being, in as much as the personality which is renewed is not changed in its essential nature, but only its functions, or parts of the personality are subjected to healing, strengthening or improvement. (Jung The Essays on Analytical Psychology 113) The renewal of the poetic activity thrills the poet and he seems to have reached his destination. The Mariner does not seem to have full faith in this stark tragedy: Oh! Dream of joy! Is this indeed The light-house top I see? Is this the hill? Is this the kirk? Is this mine own countree? (464-67) This is undoubtedly meant to recall the start of the voyage, with the cheerful company of living men: The Ship was cheered, the Harbour clearedMerrily did we drop Below the kirk, below the hill, Below the Light-house top. 66 It is one of the moments of revelation in the lives of all men. The wheel has come full circle. The familiar landmarks are the same but this only makes more terrible the memory of innocence. The Mariner is overjoyed over his successful, though strange, attempt at having reached his destination. The familiar lighthouse top, the kirk, fills him with nostalgia. The shadow of the moon is reflecting on the still waters of the harbour. The archetype of the shadow enshrines an element of surprise for him. Suddenly, he turns and sees a band of seraph men, signalling towards the shore with heavenly lights. The seraph man and his comrades are entitled to perform the function of the archetype of wise old man. The old man always appears when the hero is in hopeless and desperate situation. Since, for some internal and external reasons, the hero cannot procure the necessary material for extricating himself, the knowledge needed to compensate for the deficiency comes from the helpful old man. Confused and stunned by the proceedings, the Mariner is unable to act promptly. So the old man appears upon the horizon. With his golden hymns, the Hermit will “wash away the albatross’s blood” (512). The concluding part of the poem is focused on the redemption of the Mariner. The pilot boy points out the strange and “fiendish look” (537) of the ship. The Hermit is also struck by the peculiar quality of the ship, whose “planks looked wrapped” (529) and thin sails “he never saw aught like to him” (531). As the boat draws beneath, straight a sound was heard and ship sinks like lead. The sinking of the ship is baffling. Still it shows the power of the unconscious, and is a pointer to the fact that the ideas and impulses which rise unbidden from the depths can be both a terror and an inspiration. The bewildered Mariner finds himself in the boat. Looking at the face of the Mariner, the pilot boy shrieks and falls down in a fit. In “Kubla Khan,” Coleridge draws the picture of an inspired poet, who can construct a dome in the air with the power of imagination. Looking at the miracle, people will cry “Beware! Beware! (49) because he is a magician who has “drunk the milk of paradise.” (54) Similarly, the inspired poet shocks the Pilot boy with his outlook and he calls him a devil. As the boat touches the shore, he relates the tale of woe to the Hermit. The Hermit as the wise old man according to Jung, represents knowledge, reflection, insight, wisdom, cleverness and intuition. The wise old man usually appears in the guise of a priest or any other 67 person possessing authority. He always appears in a situation where insight, understanding, good advice, determination and planning are needed but cannot be mustered on one’s resources. This archetype compensates for the state of spiritual deficiency. The Mariner turns to the Hermit with a desperate appeal for absolution: O shrieve me, shrieve me, holy man! The Hermit crossed his brow ‘Say quick,’ quoth he, ‘I bid thee say’ -what manner of man art thou? (574-77) We are not told whether absolution is given because the emphasis is on confession. Forthwith this frame of mine was wrenched With a woeful agony, Which forced me to begin my tale And then it left me free. (578-81) Coleridge does not allow the Mariner to rest in peace. The anguish and guilt return and he is compelled to narrate the tale to whoever will listen to him. He remains a haunted wanderer, unable to find rest and peace. The Mariner’s anguished wandering between doubt and faith, fear and hope is shared by Coleridge. I pass, like night, from land to land; I have strange power of speech. (586-587) Under the spontaneous spell of inspiration, the poet acquires a strange power and words well up from his unconscious unbidden. The lines refer to the extraordinary quality infused into the poet at the resumption of inspiration. Fausset says of the stanza: I pass, like night that it is an allegory of Coleridge’s own longing to escape from the solitude of abnormal unconsciousness. The Mariner is Coleridge himself, seeking relief throughout his life in endless monologues. (Adair 318) The tragic lament changes into exultation. The load is lightened and he passes dream-like from land to land, where time is not wearisome. A loud uproar ensues 68 from the wedding house and bride-maids sing to the delight of the Mariner. With the onset of the inspiration, he is not alone, as he was: So lonely `twas, that God himself Scarce seemed there to be. (599-600) Now he is in the jolly company of “youths and maidens gay” (609). As in “Dejection,” Coleridge says, “O lady! we receive but what we give” (47) because if we find Nature in a joyful or festive mood, it is because we are ourselves in that mood. The soul is the source of joy and dejection because: The soul itself must issue forth A light, a glory, a fair luminous cloud Enveloping, the Earth. (53-55) The soul must itself send forth a sweet and powerful voice which will endow the sounds of Nature with sweetness. The soul of the poet blossoms at the renewal of this imaginative power. The poem concludes with a moral, which is an addition. The gist of the lines is that man must reconcile himself with poverty and plenty, and love all things “both great and small” (615). The poet must love the barrenness, as well as the fountain, for God had “made and loveth all” (617). Having learnt this lesson, like his wedding guest, he is: A sadder and wiser man He rose the morrow morn. (624-625) The image of the ship driving the wind is used by the poet as a conscious metaphor to express the happy surrender to the creative inspiration. Of the images of stagnant and calm and the subsequent effortless movement of the ship, Fausset says: They were symbols of his own spiritual experience, of his sense of lethargy that smothered his creative powers and his belief that only by miracle of ecstasy which transcend all personal volition, he could allude a temperamental impotence. (Jung Psychology and Religion 38) The poem weaves in its texture the archetype of rebirth, the sea journey by night when the sun is immersed in the maternal waters of the sea and is born anew in 69 the morning. According to Jung, the sea God is devoured in the West and shut up in a chest or ark, as in mother’s womb and then it travels to the East to be born anew. In his views the regression, or backward flow of the libido, that takes place when conscious or habitual adaptation fails and frustration is experienced, may be regarded as a recurring phase in development. Jung further states: It may be felt by the sufferer as a state of compulsion without hope or aim, as though he were enclosed in the mother’s womb, or in a grave-and if the condition continues it means degeneration arise in fantasy are examined for the hints, or ‘germs’, they contain ‘of new possibilities of life’, a new attitude may be attained by which the former attitude and the frustrate condition which its inadequacy brought about, are transcended. These two terms ‘frustration’ and ‘transcendence’ express the stages of the Rebirth process. (Bodkin 72) The process of rebirth is no mere backward and forward swing of the libido-such as rhythm of sleeping and waking, resting and moving on, but it is a process of growth, or ‘creative evolution’, in the course of which the constituent factors are transformed. So also Coleridge’s creative wind shows the tendency of ebbing and swelling and of sinking towards oblivion. Thus the poem exquisitely shows Coleridge’s belief that love of the calm beauty of nature will lead to love of all created things: -Of Guilty I say nothing; but I believe most steadfastly in original Sin; that from our mother’s womb our understanding is darkened; and even where our understandings are in the Light, that our organisation is depraved, & our volitions imperfect; and we sometimes see the good without wishing to attain it, and oftimes wish it without the energy that wills & performs – And for this inherent depravity, I believe, that the Spirit of the Gospel is the sole cure. . . (Griggs 396) 70 Coleridge in his another poem “The Raven” unfolds the intertwining circle of life and death in a different way. Coleridge knew that love and an atmosphere of understanding can not last forever. He saw a fiendish or dialectical image to love: hatred which often leads to death, either physical or spiritual. Death kills love regardless of the previous strong attachment. The poet uses the symbol of raven to make people aware that love cannot always win, because the powers of death are stronger. Just as the poem begins, the first circle of life is introduced: “underneath an old oak tree” (1) - The tree is old and although it has seen many a day, it could stay alive much longer if it were not for the swines which caused its death for purely selfish reasons: for their grudge. They would not have left there even a single acorn, out of which a new tree could grow, if it were not a storm that came all of a sudden. The storm is symbolic, it represents God’s intervention into the matters on the earth. The acorn that the swines had to leave there gives life to a new oak tree which gives shelter to other animals as well. The only acorn that was left begins thus a new life circle. Besides the oak tree that plays one of the prime roles, a raven enters the scene. The raven, “blacker was he than blackest jet” (9), gives the impression of a very dark day when melancholy rules and the raven is one of her companions: “he belonged, they did say, to the witch Melancholy! (8) The raven, a symbol for dreadful situations and places, has the role and attributes of a mystical creature. The raven, a conventional sign of something rather negative or pessimistic, is here used as a symbol of tragic anticipation. Besides, “it not only bodes death, but…some say that ravens foster forlorn children whilst their own birds (younger ones) famish in their nest.” (Vries 382) In this sense, the raven could be seen to parallel a similar relationship between Coleridge and his father. The Reverend John Coleridge was always preoccupied with the parishioners at Ottery St. Mary and young Coleridge felt he never got enough attention, time, and love from his father. The raven, which is largely used as an epitome of sadness, acquires in this poem just the opposite qualities. The raven finds his mate after enormous effort and they abide in happiness, which is short-lived. 71 The harmonious life of the birds is violently destroyed. The tree where the birds had their nest is cut down by a woodman, the raven gets furious and wishes for severe recompense for death of his young ones “and their mother (who) did die of a broken heart.” (30) There again life is surpassed by death and the life and death circle intertwine suggesting the never ending rotation of life and death. In ‘The Raven”, the recompense comes in as a satisfaction for the bird; and for it to be true recompense, it has to be compensated by the death of some other creatures, especially that of the woodman. The raven takes delight in observing the woodman die in a cruel way similar to the way his young ones died. When the woodman came to cut down the oak tree where the raven had its nest, the raven could no longer retain his rather uncommon role of representing something positive. He changed from the temporary representative of happiness and love to his traditional position: the representative of death, namely, of death out of revenge. The whole tragedy happens due to the felling of an oak tree. The raven had its nest in its crown, and there seemed to be a perfect symbiosis between the raven and the tree. In the biblical symbolism, a tree might stand for a life-giving strength, for a shrine, and, moreover, a green tree is a symbol of an honest person blessed by God. The oak tree then, brings up the connotations of closeness, longevity, immortality and regeneration. (Vries 347) When the oak tree is cut down, its strength irrevocably passes. A felled oak tree represents a case of fatal mistake by the woodman. He came to cut down the tree because he wanted to use its wood for selfish purposes. The woodman used the oak wood to make a ship, but, absurdly, this ship became his coffin. It is again symbolic because coffins are very often made of oak. Here the symbol of life turned into a symbol of death. Coleridge uses the symbol of an oak tree repeatedly as it perfectly fits into his imaginative world. Relating the poem to the social context of the time, the raven, the oak tree, and other symbols aside from other meanings, Coleridge’s disappointment and fear of the French Revolution of 1789. The ship was symbolically caught in a storm, and it “bulged on a rock, and the waves rushed in fast.” (37) The raven appears above the scene of destruction like an angel of death: 72 Round and round flew the raven, and crawl to the blast, He heard the last shriek of the perishing soulsSee! See! ov`r the topmast the mad water rolls! Right glad was the Raven, and off he went fleet, And Death riding home on a cloud he did meet, And he thnk`d him again and again for this treat: They had taken his all, and REVENGE IT WAS SWEET! (38-44) The suffering of the bird becomes an image of man’s guilt and vengeance is wreaked. The storm symbolically reflects the turmoil of the changes in the society at the end of the eighteenth century. The old faith, symbolised by the oak tree, is undermined and no certainty remains, everything seems to be uprooted. Still the situation might offer a chance for regeneration. The characters in “The Raven” and the representatives of the French Revolution share a primary noble intention, but the circumstances and selfish human factors do not allow either of them to carry out their noble intentions as they wished. Love and desire for freedom were corrupted for selfish goals in France. Similarly, the freedom of raven living on an oak tree is taken away from it by the woodman. The enthusiasm is changed into contempt and disillusion. There was much disappointment because of the violence used; in France, the violence peaked in the later stages of the revolution, and, in the case of the raven, the violence found its greatest horror at the point of felling the oak tree. Not violence and blood but peaceful life should have been the result of the Revolution. Instead, a dark and almost deathly period in French history set in. There is a new parallel in “The Raven”. The bird lost everything it had yearned for and loved so much, and it has no joy anymore. Its love is gone and it only waits for death to end its life. Coleridge often may be even unconsciously, contrasted his symbols in dialectical pairs. A dialectic to raven is a rose, a symbol which occurs frequently in his poems. Coleridge uses both as attributes of love. The rose is its positive manifestations, whereas the raven stood for its negative counterpart. Their antithetical character is emphasised by their colour symbolism: the rose is frequently either white 73 growth’ but also purity, and immaculation, red-“love and battle”, and black- “deathdivination”. (Vries 108) In this sense, they could be understood as symbols of the lifeplace in the heart, it culminates in the true passion, but either some hatred or the anticipation of death spoils it. Finally lovers are separated by death which causes an end of one life circle. So, in my opinion, the rose and the raven could be seen as dialectic. They both approach the same idea, but from different ends. However, they both signalise a kind of disaster for love and life. Coleridge, however, had second thoughts about the ending of the poem and added two lines after it: We must not think so; but forget and forgive, And what Heaven gives life to, we’ll still let it live. (Adair 38) But this excellent thought weakens the sombre force of the original whose power lies in its starkness. Nor was Coleridge satisfied with his addition, for he added a curious note: Added thro cowardly fear of the Goody! What a Hollow, where the Heart of Faith ought to be, does it not betray? This alarm concerning Christian morality, that will not permit even a Raven to be a Raven, nor a Fox a Fox, but demands conventicular justice to be inflicted on their unchristian conduct, or at least an antidote to be annexed. (Coleridge, E.H. 171) Thus the poem speaks about the interdependence of life and death through symbolic, metaphorical and allegorical devices because they offered him the opportunity to show interdependence of nature, man and God in a very complex way. In “Dejection: an Ode”, Coleridge equates death to the loss of his imaginative power: I may not hope from outward forms to win The passion and the life, whose fountains are within. (Coleridge, E.H. 365) The reason is that Coleridge has lost the joy and hope of human love, the capacity to feel and with it his imaginative power. In “A Letter to Asra” and “Dejection,” 74 Coleridge has reached a turning point in his personal and creative life. He has lost his Platonic vision of the Absolute and can no longer take refuge in dreams and shadows. The firelight image flickers in the “Letter to Asra” but for the last time; in “Dejection” it disappears. He recognises that feeling has become completely separated from form: -What then? Shall I dare say, the whole Dream seems to have been Her-She. . . Does not this establish the existence of a Feeling of a Person quite distinct at all times, & at certain times perfectly separable from, the Image of the Person? (Coburn 209) This separation of feeling from form marked the death of his imagination. Coleridge treats the motif of death in a different way in “The Wanderings of Cain”. The poem opens in a dark forest, where Cain is making his way with difficulty, and where the darkness becomes a correlative for his own sense of guilt and oppression. While his son, the innocent child of nature, Enos, leads him into the moonlight, Cain searches restlessly for ‘the God of the dead’. (Coleridge, E.H. 292) Coleridge in discussing the relation between sublimity and fear, associates it more naturally with the phenomenon of genius. Genius, according to him, differs whether it is associated with life or death. The man whose genius is associated with a strong sense of life is happy and self-contained. He drinks his own genius as at a selfrenewing fountain and creates his works of art with the effortlessness of a sun rising and illuminating the entire landscape. But if his consciousness includes a strong sense of death, the nature of his genius becomes correspondingly different. The very objects which before reflected his sense of his own immortality and were splendid now become objects of fear to him. He becomes obsessed by savage and ruinous places which speak more directly to his new fears. (Beer 58) It was in Cain’s murder of Abel that the sense of death in man had first been made actual; in killing his brother he had also become aware that he himself would one day cease to be. Adam in Eden had known the state of absolute genius: the sunilluminated garden and the self-renewing fountain which reflected the light of the sun. But Cain found it more natural to seek out desolate places, whose gloom suited his new sense of death. Anything associated with his former sense of immortality was 75 now an occasion of fear. When he and his descendants came to any place which reminded them of the lost glory they treated it with awe and respect and sought in some way to propitiate of the power which they sensed there. The descendents of Cain built enclosures sacred to the sun in a vain attempt to regain the glory of their lost paradise. ((Berkley 119) This brought into play two themes: the image of the sun enclosure by the sacred river and the consciousness of death which Cain’s crime brought into the world. These two themes are brought together in the lines which intervene between those describing Kubla Khan’s ‘decree’ in the poem “Kubla Khan” and those which amplify Purchas’s description: Where Alph, the sacred river, ran Through caverns measureless to man Down to a sunless sea. (1-3) The river Alph runs down through hollow caverns to a sea of death which is devoid of sun. It thus becomes a perfect image for Kubla’s basic death-consciousness, that the very abyss in himself which urges to the construction of a place of pleasure as a refuge from it. Everything in the garden corresponds to what was known of ancient sun-worship: the circular enclosure itself, the bright streams shining to the sun, the incense which was burnt in its worship, the forests, their darkness relieved by sunny ‘spots of greenery’. But the same images also convey a potent sense of immortality. Fraught by the prospect of death, this son of Cain surrounds himself by fertile ground, by an endless maze of rills, by incense (which whenever its scent is perceived gives one a sense of the timeless) and undying forests. Thus Coleridge’s Cain is haunted by emblems both of death and of a lost glory and acts as a reminder of total joy and fear. (Beer 71) In “Kubla Khan,” Coleridge equates the motif of death and rebirth with the loss of poetic inspiration and then regaining it. The poem which is a product of dream lays stress on the repressed desires in the unconscious mind of Coleridge. Freud’s theory of the dream brings into focus the desires and urges which might have occasioned Coleridge’s mental state at the time he came to write this poem. The desires in the unconscious impelled him to attain great poetic height but his sickness held him from doing so. The dark caverns in the poem from which the river rises to 76 flow through sunlit garden suggest the different levels of creative power. It is symbolic of the flow of poetic inspiration, in the framework of the garden with fragrant blossoms and the pleasure-dome that suggests the operation of the conscious. The river is definitely the river of poetic inspiration and it is sacred because Coleridge equates poetic activity with the gift of God. In the first stanza, Coleridge describes the spontaneous flow of the river. When the river of poetic inspiration falls into the unconscious, the mind becomes a haunted place, which has been visited by a woman wailing for her demon lover. The darker side, the unconscious, engulfs the river of the poetic inspiration. Jung states that mankind has never lacked powerful images to lend magical aid against all the uncanny things. The phrase ‘waning moon’ invites comparison with the following lines in “Dejection: an Ode:” For lo: the New winter bright: Overspread with phantom light. (9-10) In these lines Coleridge laments the loss of poetic inspiration and compares it with the eclipsing of the moon. Similarly, the woman wailing for the demon lover under the waning moon along with the savage and haunted place echo the same feeling of loss. The lines suggest certain demonic powers, evil influences which are at work during its operation. The use of the word “woman” is significant. Jung believes that in the unconscious of every man, there is a feminine element personified in dreams by a female figure or image, in the name of the “anima”. It is due to the influence of the mother and the inherited image of the racial idea of woman derived from man’s experience. In this regard, Jung says: Every man carries within him, the external image of woman. . . an imprint or archetype of all the ancestral experiences of the female, a deposit, as it were, of all the impressions ever made by woman. . . in short, an inherited system of psychic adaption. (Bennet 127) The mysterious aura of Coleridge’s woman in the poem can be explained through the following statement of Jung: 77 With the archetype of the anima, we enter the realm of the Gods, or rather the realm that metaphysics has reserved for itself. Everything the anima touches becomes numinous- unconditional, dangerous, taboo, magical. (Jung The Archetypes of Collective Unconscious 28) Through the eruption of the fountain, the lines ahead enable the reader to watch a violent process: Huge fragments vaulted like rebounding hall, Or chaffy grain beneath like thresher’s flail; And mid these dancing rock at once and ever It flung up momently the sacred river. (21-24) The use of the word “fountain” is significant because in “Dejection: an Ode”, Coleridge equates poetic inspiration with the fountain: I may not hope from outward forms to win The passion and the life, whose fountain are within. (45-46) With “swift half-intermitted burst” the fountain forces its way. The phrases like “ceaseless turmoil” (17) and “fast thick pants” (18) show the turmoil that goes on in the poet’s subconscious. The mind makes an effort to revert the harmonious flow of the river of poetic inspiration. The analogy with the rebounding hail and the thresher’s frail describes the agony that the poet’s mind undergoes in the process of creation. The crust, the unconscious which has engulfed the subconscious is broken. On account of the conscious effort t, the river rises from the underground. In another context, the lines suggest that the river rises in the fountain with continuous pressure and flows through the ‘deep romantic chasm’ (12) called a ‘savage place . . . holy and enchanted’ (14) such as where a woman would wail for reach of the demonic mind. Likewise the chanting poet is wailing for his demonic inspiration to return. In this regard, “savage” implies not the brutal, but the primordial, the time before man’s consciousness evolved the dualism of the good and evil. Earlier the poetic inspiration was spontaneous and free. In the depth of the unconscious, it perceives the embers of the freedom that still resides there. 78 The course of the river is still not smooth. It is “meandering with a mazy motion” (25). After running through the dale, it again reaches the dark caves and sinks with “tumult into a lifeless ocean” (28). The word “tumult” suggests the agony, the chaos, the nothingness suggestive of the process of association and disassociation of images in the subconscious of the poet. The process of the flow of poetic inspiration starts with half intermittent bursts. It comes to the meandering motion and falls into a state of chaos. The tumult reminds Kubla Khan of war. The tumult denotes the message that war is yet to be fought against the power of darkness, the evil, which Kubla Khan thought has come to an end. The tumultuous sound heard on account of the falling of the river into a lifeless ocean, reminds the poet that his conscious effort would be rewarded and the meandering river would flow smoothly. The eclipse vanishes and the shadow that fell on the river disappears too. The “shadow” is another archetype representing the evil latent in man. It comprises not just those undesirable traits which are repressed into the personal unconscious, but the whole ugly burden of the evil of world. Similarly, the shadow that fell on the river stands for the dark influences, the evil which is an impediment in the way of the conscious, or the spontaneous flow of poetic inspiration. The revival gives the poet “mingled pleasure” (33), the pleasure of creating “a miracle of rare device” (35) because he creates a paradox “a sunny pleasure dome with caves of ice” (36). The sacred river that dominates the first thirty lines of the poem, runs through dark caves, flows down to a sunless sea and sinks in tumult into a lifeless ocean. This is an effective way of symbolising the glittering structures welling up from the subconscious and are recognised by the conscious. These structures again sink into the recesses of the subconscious, where they disintegrate and become lifeless. Untouched, they well up into the conscious again to acquire life. Thus the sacred river is symbolic of the poetic mind delineated in the poem. It strongly suggests the extent to which the subconscious is the producer of the strange beauty in “Kubla Khan” and the demon beset subconscious is both creator and destroyer. In the second part of the poem, there is again rebirth of poetic inspiration. The second part is the logical extension of the first. The impression is the subconscious 79 travel to the conscious and the state of inactivity is replaced by that of activity. The ceaseless turmoil, half intermittent bursts are overcome and the imagination soars, and he drifts into heaven, where he sees a damsel with a dulcimer singing on Mount Abora. Here the archetype of the anima is brilliantly employed. The poet relates this vision of damsel chiefly with the awesome and mysterious power of poetic creation, which gives delight. In the process, he loses all conscious control and becomes intoxicated with the divine madness. Jung’s view would be valid here, who says that no sooner the unconscious touches a person, he becomes unconscious of himself. In the next stanza, Coleridge draws the picture of a poet under the spell of poetic frenzy: . . . Beware Beware his flashing eyes, his floating hair! Weave a circle around him thrice, And close your eyes with holy dread, For he on honey dew hath fed, and drunk the milk of paradise. (49-54) With the power of his imagination, Coleridge will build that dome in air, the sunny dome with caves of ice, for that is the inventive power of his poetry. He will be regarded with awe like Kubla Khan who is the figure of power, mystery and enchantment. He will be synonymous with the youth who has eaten the fruit and drunk the milk of paradise, forbidden but in the poet’s vision possible only through the participation mystique which involves what Jung has called the release from compulsion and impossible responsibility. As a result the psychic energy is released on to an invisible centre, which is also the circumference that enclosed the conscious and the unconscious as in erotic union. The poem is woven around the motif of death and rebirth that is symbolic of losing poetic inspiration and then regaining it. Coleridge gives a sustained account of the creative power of poetry. Alph, the sacred river is the river of the Muse, that is, the poetic imagination itself. The poem that begins with the river flowing into the underworld and ends with divine madness, is also about the source of creative inspiration. Thus Coleridge is a pioneer in the field of Psychology who gives us a sustained account of the working of the unconscious, subconscious and conscious mind of the poet. As Jung says: 80 many artists, philosophers and even scientists owe some of their best ideas to inspiration that appears suddenly from the unconscious for example, the French mathematician Pioneare and the chemist Kekule owed important scientific discoveries to sudden pictorial revelations from unconscious. Robert Louis Stevenson had spent several years of a story when the plot of Dr. Jekyl and Mr. Hyde was suddenly revealed to him in a dream. (Bennet 75) In another poem “Self-Knowledge,” the motif of rebirth acquires a different meaning. The poem deals with the old Greek maxim, ‘know thyself’ which Coleridge finds impossible: What is there in thee, Man, that can be known? Dark fluxion, all unfixable by thought, A phantom dim of past and future wrought. (Coleridge, E.H. 487) There is moment of rebirth for Coleridge when he turns to God Who may offer a solution: Vain sister of the worm - life, death, soul, clodIgnore thyself, and strive to know thy God! (Adair 236) Coleridge’s “Epitaph” which he wrote a few months before his death, recalls The Ancient Mariner. The poem treats the motif of death in a different way. The ghost of Life-in-Death which had haunted him so long is nearly laid: Stop, Christian passer-by!-Stop, child of God, And read with gentle breast. Beneath this sod A poet lies, or that which once seem`d he O, lift one thought in prayer for S.T.C.; That he who many a year with toil of breath Found death in life, may here find life-in-death! Mercy for praise- to be forgiven for fame 81 He ask`d and hoped, through Christ. Do thou the same! (1-8) Death also appears lovely in Coleridge’s “Religious Musings”. The loveliness of death refers implicitly to the ethical and spiritual value or ideal for which the individual surrenders his life. In the “Religious Musings” Coleridge writes: Lovely was the death Of whom whose life was Love. ( 29-30) This is a death within time while the lovely transcends space and time. The transcendence is communicated by the word ‘love’ which refers to all-inclusive love. Coleridge’s beautiful poem “Psyche” is exquisitely woven around the motif of rebirth when he becomes aware of the true nature of love. He writes in an entry of April, 1805: . . . Worthiness, Virtue consist in the mastery over the sensuous and sensual Impulses-but Love requires INNOCENCE. . . This is perhaps the final cause of the rarity of true Love, and the efficient and immediate cause of its Difficulty. Ours is a life of Probation/. . .To perform Duties absolutely from the sense of Duty is the ideal, which perhaps no human being can ever arrive at, but which every Human being ought to try to draw near unto-This is-in the only wise and verily, in a most sublime sense-to see God face to face/which alas! It seems too true that no one can do and live, i.e a human life. It would become incompatible with his organisation, or rather it would transmute it, & the process of that Transmutation to the sense of other men would be called Death-even as to Caterpillars in all probability the Caterpillars dies- & he either does not see, which is most probable, or at all events he does not see the connection between the Caterpillar and the Butterfly- the beautiful Psyche of the Greeks. Those who in this life love in perfection, if such there to be as 82 in proportion as their Love has no struggles, see God darkly and thro’ a Veil. (Coburn 114) This recognition that true Love can never be achieved in the ordinary human condition is a kind of revelation to the poet. ‘Ours is a life of probation’- the ideal can not be achieved. ‘Psyche’ meant for the Greeks both ‘butterfly’ and ‘soul’ and they depicted the soul flying from the dead man’s mouth in the form of a butterfly. This free and winged state can never achieved in human life and, in trying to reach it, we hurt and destroy others in the name of love, as the butterfly destroys the caterpillar. Thus the motif of death and rebirth acquires different meaning in Coleridge’s poetic world with the changing vision of the poet. 83 WORKS CITED PRIMARY SOURCE Coleridge, Hartley Ernest, ed. Coleridge Poetical Works. London: Oxford University Press, 1912. Print. SECONDARY WORKS Abrams, M.H. “The Correspondence Breeze: a Romantic Metaphor,” English Romantic Poets: Modern Essays in Criticism, ed. M.H.Abrams. New York 1976. Print. Adair, Patricia. M. The Waking Dream. London: Edward Arnold, 1967. Print. Beer, John. Coleridge the Visionary. London: Oxford University Press, 1959. Print. Bennet, E.A. What Jung Really Said. London: Macdonald, 1966. Print. Berkeley, George. The Principles of Human Knowledge. London: Oxford University Press, 1942. Print. Coburn, K. The Philosophical Lectures of Samuel Taylor Coleridge. New Jersy: Princeton Press, 1949. Print. Hill, John. Spencer. A Coleridge Companion. London: Macmillan Press, 1983. Print. Griggs, E.L. Collected Letters of S.T.Coleridge. London: Oxford University Press, 1959. Print. Jung, C.G. Symbols of Transformation. New York: Pantheon Books, 1953. Print. . . . , Two Essays on Analytical Psychology. New York: Pantheon Books, 1953. Print. . . . , The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. New York: Pantheon Books, 1956. Print. . . . , Four Archetypes. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1980. Print. Kessler, Edward. Coleridge’s Metaphor of Being. New Jersy: Princeton Press, 1979. Print. Raysor, T.M. Coleridge’s Miscellaneous Criticism. New York: Princeton Press, 1936. Print. 84 Schulz, Max. F. The Poetic Voices of Coleridge. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1964. Print. Suther, M. The Dark Night of Samuel Taylor Coleridge. New York: Princeton Press, 1960. Print. Vries, Ad de. Dictionary of Symbols and Imagery. Amsterdam: Northholland, 1976. Print. Warren, R. P. ‘A Poem of Pure Imagination,’ Kenyon Review, vol. viii, 1946. Print. Whalley, George. “On Reading Coleridge,” Writers and their Background S.T. Coleridge, ed . R.L Brett. London: G. Bell & Sons, 1971. Print. Yarlott, Geoffry. Coleridge and the Abyssinian Maid. London: The Broadwater Press, 1967. Print.