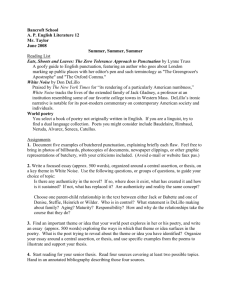

Grieving & Memory in DeLillo's Falling Man: Transatlantic Perspectives

advertisement

Terrorism, Media, and

the Ethics of Fiction

Transatlantic Perspectives on Don DeLillo

Edited by

Peter Schneck and Philipp Schweighauser

-~

continuum

NEW YORK •

lOifDOtl

CHAPTER

2

GRIEVING AND MEMORY IN DoN DELILLo's FALLING MAN

Silvia Caporale Bizzini

The task of the mind is to understand what happened, and this understanding,

according to Hegel, is man's way of reconciling himself with reality; its actual end

is to be at peace with the world.

(Hannah Arendt, "The Gap between Past and Future")

She read newspaper profiles of the dead, every one that was printed. Not to read

them, every one, was an offense, a violation of responsibility and trust. But she

also read them because she had to, out of some need she did not try to interpret.

(Don DeLillo, Falling Man)

In a work in progress entitled "Memory, Autobiography, History," John F.

Kihlstrom refers to trauma therapy as a means of recovering memories from

the past in order to reconstruct the reality that has been banished by tragic

events in individual lives.' Remembering is seen as a way to reconstruct a lost

world and a lost perception of self. Within a completely different disciplinary

context, but with the rise of totalitarianism in mind, Hannah Arendt focused

on the importance of tradition and remembrance in the perception of one's

identity, understood both as individual awareness of self and as a feeling of

belonging to a community. Human consciousness originates from the {cultural)

dialogue that we maintain with our past, and that situates us in the present;

when we are deprived of these points of reference, a crisis results:

For remembrance, which is only one, though one of the most important, modes

of thought, is helpless outside a pre-established framework of reference, and the

human mind is only to the rarest occasions capable of retaining something which

is altogether connected [... ] without the articulation accomplished by remembrance, there simply was no story left that could be told. (Arendt 1977, 5-6}

Remembrance, then, is a primary element in the process of ontological reconstruttion, but it is not the only one I am interested in: the other is storytelling

as public performance. In Men in Dark Times (1968), Arendt points out that

to perform in public is a political act because the subject is made visible by

having his or her message seen and heard by many. This idea also informs The

Human Condition (1998) where Arendt elaborates on her understanding of

storytelling as an act of freedom and a move into public discourse: the realm

of the polis understood as democratic dialogue. 2

I believe that Don DeLillo's Falling Man (2007) makes a political statement

in its negotiation of these two concepts: remembrance and storytelling. At the

same time, DeLillo's novel moves away from more classical conceptions of

Grieving and Memory in DeLillo's Falling Man

41

narrative in order to focus on a small group of characters whose struggles

stand in for a collective condition. Falling Man does not represent collective

paranoia but seeks to understand, through depictions of grief and memory

work, the events that took place on September 11, 2001, thus transforming

them into shared memories and starting the process of healing. DeLillo's novel

is an ambiguous text, a reflection in progress that projects onto the reader the

epistemological chaos, insecurity, and uncertainty of Western societies in the

wake of 9/11.

In "Falling Towers and Postmodern Wild Children," James Berger uses the

Biblical reference to the destruction of the Tower of Babel as a metaphor to

refer to the violent diSappearance of the known social order after the terrorist

act, the coming of a chaotic perception of the real, and the ensuing collective

trauma. Berger points out that language becomes the site of ontological and

epistemological tensions at the same time that individuals project onto it the

necessity to voice their traumatized selves:

Language is broken-has been traumatically broken-yet remains nevertheless

ideologically imprisoning. There is some other language (whether divine, traumatic, or neurological), but we have only our existing broken language with

which to summon and encounter it. Thus, the transcendent can only be expressed

or addressed in terms of the traumatic. (Berger 2005, 346)

According to Philip Tew, novels published after 9/11 can be considered as

belonging to "a traumatological rather than postmodern bent" (2007, 190}.

The traumatological, he insists, is rooted within certain historical circumstances that simultaneously blow apart both our sense of identity and the social

order. Tew draws a clear distinction between "trauma-culture fiction" {192)

and the traumatological. The first originates in the subject's private life-story

and is, at times, representative of the impossibility of coming to terms with

the order of things that surrounds us, while the latter aims at analyzing ho·w

groups respond to what is considered as a common threat in a clearly defined

historical moment in time and space.

My point is that Falling Man does not aim to tell a story that is centered on

the spectacle of terrorism and terror, even though it retains most of DeLillo's

fictional themes and theoretical nodal points such as the analysis of postmodern society or his interest in the power of images, in language, and in cultural history. Rather, DeLillo's 9/11 novel probes how we react to terror and

how we seek reasons in order to come to terms with a reality that is falling to

pieces not only metaphorically but also physically. This is exemplified by the

beginning of Falling Man and of Keith Neudecker's story. The text starts with

a third-person n~rrator and with short and broken sentences in order to stress

the sensation of chaos and loss of understanding:

The world was this as well, figures in windows a thousand feet up, dropping into

free space, and the stink of fuel fire, and the steady rip of sirens in the air. The

noise lay everywhere they ran, stratified sound collecting around them, and he

42

Terrorism, Media, and the Ethics of Fiction

walked away from it and into it at the same time[ ... ]. He kept on walking[ ... ]

and things kept falling. (4)

In this apocalyptic context, storytelling and writing become both the means of

a verbal reconstruction of tradition and the real and the point of contact

between characters that people an apparently choral novel but who inhabit

different existential spheres.

1. Writing the Trauma

Alex Houen states that "A trauma that is so real it can only be experienced as

a kind of fiction" (419). He goes on to explain that writing can convey the

lived tragedy but is only partially able to transform it into images: "For anyone

who was an actual victim, what lay at the heart of the disaster was the traumatic crossing between mediation and visceral reality" (419). 9/11, it seems,

has brought forth a reality too harsh to be true, too hard to believe, and never

before experienced by North Americans. Against that background, it is linguistic mediations that allow us to assimilate the events on 9/11 and to engage in

a kind of collective scriptotherapy that enables us to work through the mourning. Houen reminds us that in the days following the terrorist attack, various

periodicals requested writers to transform the tragedy into words in order

to give voice to collective grieving, to come up with "personal responses that

could translate suspension of belief into emotional eloquence for a public

forum" (420). Houen then refers to the introduction ofUlrich Baer's anthology

110 Stories: New York Writes After September 11 (2002), quoting Baer's categorization of writing modes in relation to the attack:

One way is as therapeutic absorption, whereby stories "transform even [the]

most violent transformations by shaping them into words" [Baer 2002, 3]. [... ]

A second way is as "unconscious history-writing of the world: as a form of

expression that uncannily registers subtle shifts in experience and changes a

reality before they can be consciously grasped to have fully taken place" [5].

The third way, which Baer specifically associates with novels, is as apotropaic

defense. (Houen 2004, 421)

Whil.e Baer relates writing and memory to the grieving and healing process,

Anthony Kubiak follows Roland Barthes in understanding narrative as the

process of transforming memory and the unconscious into words: "The principle of narrative then, supersedes 'the literary,' the mythic, the ideological, and

even in some sense, the syntactic. Narrative seems [...} somatic, organic, the

physical impulse of consciousness itself" (295). Kubiak suggests that terrorism

aims at telling its stories not through its victims' gaze but through the spectators' gaze: "The ability of narrative (fictional or not) to construct a world that

is fearful, uncertain and dangerous is its link to terror" (298). Moreover, he

reminds us of Paul Ricoeur's contention that the main aim of stories is to (re)

Grieving and Memory in DeLillo's Falling Man

43

create time and history as each narrative, from fiction to autobiography, determine a timeline through the use of memory (299). In fighting back the spectacle of terror as a crucially significant element of the contemporary definition of

the real, DeLillo meets the writer's responsibility not to forget by writing about

the victims' memory, their pictures, and their personal objects. It is in this sense

that he writes:

The cell phones, the lost shoes, the handkerchiefs mashed in the faces of running

men and women. The box cutters and credit cards [... J These are among the

smaller objects and more marginal stories in the sifted ruins of the day. We need

them, even the common tools of the terrorists, to set against the massive spectacle

that continues to seem unmanageable, too powerful a thing to set into our frame

of practiced response. (DeLillo 2001, 35)

In Falling Man, each of the main characters carries out a solitary negotiation

with a reality that has been shattered by a barbaric act of seemingly nonsensical cruelty and the resulting feeling of defenselessness. In such a trawnatic

context, memory is transformed into something real through the "narrative

drive" (Kubiak 2004, 295). For instance, once a week, Lianne Glenn, Keith's

estranged wife, meets a small group of people suffering from the first symptoms of Alzheimer's disease. The therapeutic session focuses on remembering

their lives, perhaps the last chance they will have to be able to connect their

present with their past before both fade for good. They first write about their

storyline and then read it aloud:

Sometimes it scared her, the first signs of halting response, the losses and failings,

the grim prefiguring that issued now and then from a mind beginning to slide

away from the adhesive friction that makes an individual possible. It was in the

language, the inverted letters, the lost word at the end of a struggling sentence.

It was in the handwriting that might melt into runoff. But there were a thousand

high times the members experienced, given a chance to encounrer the crossing

points of insight and memory that the act of writing allows.[ ... ] They worked

into themselves, finding narratives that rolled and tumbled, and how natural it

seemed to do this, tell stories about themselves. [...] l\.1embers wrote abour hard

times, happy memories, daughters becoming mothers. Anna wrote about the

revelation of writing itself, how she hadn't knmvn she could write ten words and

now look whar comes pouring out [... ] There was one subject the members

wanted to write about, insistently, all of them bur Omar H. It made Omar nervous but he agreed in. the end. They wanted to write about the planes. {DeLillo

2007, 30-1)

The narratives of these people-Carmen G., Benny T., Rosellen S.-highlight

their struggle against the deterioration of an irretrievably fading perception of

self in the painful and unstoppable progression of the disease. They clearly situate themselves as resilient subjects because their narratives are a way to structure what is left of their life experience in the private and public spheres insofar.

As Paul John Eakin suggests, "narrative is not merely a literary form but a

mode of phenomenological and cognitive experience" (115). These characters

44

Terrorism, Media, and the Ethics of Fiction

fight against Alzheimer's disease and at the same time contradict theorizations

of the society of the spectacle, specifically the notion that history and memory

are substituted by images and the commodification of culture so that any lived

experience is converted into an apparently eternal present that leads to collective amnesia (Best 1995, xii). Theirs in an act of resistance that testifies to the

fact that, "after all, words do represent people and things" {Wilson 1995, 57).

These characters also defy Philip Tew's distinction between "trauma-culture

fiction" and "traumatological narrative." In their case, memory and writing

help in a double process of healing; the private fight against disease and-in

terms of the Arendtian polis-the public need to recover and/or preserve memories to strengthen ties with the public realm of (historical) collective grieving.

2. Negotiating Tradition

One of Hanna Arendt's most basic and crucial notions is that of "traditional

categories," understood as realizations of "the binding authority of tradition"

(Kohn 1997, xxi). When such categories are violently shattered {as in the case

of Nazism and other totalitarian regimes), our old sense of self is at stake

because, as Kohn aptly puts it, it is extremely "difficult [... ] for anyone to

think for him- or herself in the gap that separates the 'no longer' from the 'not

yet'" (xxi). In Between Past and Future (1977), Arendt insists that tradition

gives to us the cultural categories that we use to name what defines our reality

and our understanding of ourselves as individuals:

lj

l

l

I'

l

I

I

l

Without testament or, to resolve the metaphor, without tradition-which selects

and names, which hands down and preserves, which indicates where the treasures are [... ]-there seems to be no willed continuity in time and hence, humanly

speaking, neither past nor future. (5)

Anne Longmuir points out that "[c]ritics have frequently remarked about

DeLillo's prescience: after September 11,2001, DeLillo's longstanding engagement with the relationship of the United States to the Middle East and Islamic

fundamentalism confirms him as one of America's most important and shrewd

cultural commentators" {105). From this perspective, Falling Man does retain

the nodal points that define his writings but at the same time, it presents a tense

duality and ambiguity in relation to the role that tradition plays within the

novel and how some of the characters in the text cling to their traditional

cultural values in their attempt to redefine their subjectivity. Berger suggests

that people who suffer from trauma because of a personal encounter with violence and experience of pain feel the need to restore the epistemological and

ontological points of references they had prior to the upheaval that devastated

their lives: "The logic and desire both of terrorism and of antiterrorism are to

restore the imagined former state: of social harmony and perfect correspondence between word and thing" (343). Thus, people affected by trauma seek to

J

Ii

I3

§

I

l

Grieving and Memory in DeLil/o's Falling Man

45

recover the old shattered symbolic order and, in order to do so a new identifir.:ation with traditional cultural values can be seen as a way to heal their

wounded selves. In The Names (1982), for example, DeLillo's reference to

ancient languages and language is a constant presence in the text, but in the

end, as Longmuir suggests (106), we wonder if language in this novel is ever

more than a kind of intellectual game in the wake of structuralism and other

inspiring and appealing language theories. In contrast, in Falling Man, Lianne's

interest in and near obsession with ancient languages and old books details her

search for a link between her beliefs and those of other cultures. Her work as

an editor allows Lianne to retain a critical connection with her own cultural

tradition, the rational thought that has defined and structured her individuality

and liberal frame of mind:

There were the scholars and philosophers she'd studied in school, books she'd

read as thrilling dispatches, personal, making her shake at times, and there was

the sacred art she'd always loved. Doubters created this work, and ardent believers, and those who's doubted and then believed, and she \vas free to think and

doubt and believe simultaneously. (DeLillo 2007, 65)

It is because of this need for rationality and the responsibility for understanding the reasons of the other that Lianne desperately wants to edit a book no

other editor is willing to accept: an essay on plane hijacking written by a retired

aeronautical engineer: "Lianne didn't care how dense, raveled, and intimidating the material might be or how finally unprophetic. This is what she '\vanted"

(139-40). She edits this manual at the same time as another difficult and

demanding text, one on ancient languages, a mixture of written and graphic

codes that together impart to her a sense of disappeared cultures that link her

present with a past that she can only imagine. In the process, her coming to

terms with the tragedy is channeled through the written word and a logical,

consistent effort to control her grieving and her response to suffering. Lianne's

need to deal with terror and personal fear is related to a deeper necessity to

know if two cultures--<lne represented by the book on ancient languages (the

past) and the other represented by the book on hijacking (the present)-can

ever come to know and understand one another.

Nonetheless, this self-protective attitude is suddenly shaken by the rage she

feels when she hears music with an Arabic resonance coming persistently from

her neighbor's flat. At Lianne's enraged verbal attack, Elena, her neighbor,

calmly answers back: "It's music. You want to take it personally what can I tell

you?" (119). While words and images are there as subtexts that allow Lianne

both to recuperate and interrogate tradition rationally, the exoticism of the

music powerfully touches her on a more intimate, transcendent, and unconscious level and presents a challenge to her rationalizing response to suffering.

Lianne can face reading a table full of numbers on hijacking or decode ancient

writings but she cannot deal with the other's emotional roots when her own

emotions of trauma and suffering are being liberated from the cage of rational

understanding imposed on her from without.

46

Terrorism, Media, and the Ethics of Fiction

As already indicated, Arendt in Between Past and Future firmly proclaims

that a historical time continuum in rational terms is only possible if we retain

those names and words from the past that guide us and help us preserve our

capacity for telling our own (his)story: "[W]ithout the articulation accomplished by remembrance, there simply was no story left that could be told"

(1977, 6). Elsewhere, she adds that it is always through remembrance that the

work of art defies mortality (Arendt 1998, 43 ). Nina Bartos, Lianne's mother,

is a fine intellectual and a staunch defender of the cultural tradition she has

taught and written about during her academic career as a Professor of Art

History. Nina is resisting both her poor health and the trauma caused by the

bombing, which has caused a private and a public suffering that she fights the

only possible way she knows:

[SJhe walked up the street to the Metropolitan Museum and looked at pictures.

She looked at three or four pictures in an hour and a half of looking. She looked

at what was unfailing. She liked the big rooms, the old masters, what was unfailing in its grip of the eye and mind, on memory and identity. Then she came home

and read. She read and slept. {DeLillo 2007, 11; my emphasis)

Tradition, as stressed above, is at the heart of the conversation we have with

ourselves and with our consciousness, and Nina is firmly intent on not interrupting that dialogue. Nevertheless, as Lianne's inner conflict highlights, the

relationship that contemporary Western societies maintain with tradition is

marked by tensions and a constant questioning of inherited cultural categories.

That tension is also negotiated by Nina Bartos and Martin Ridnour, her

German lover of 20 years, an art merchant who in his youth supported the

radical left:

He was a member of a collective in the late nineteen sixties. Kommune One.

Demonstrating against the German state, the Fascist state. That's how they saw

it. First they threw eggs. Then they set off bombs. After that I am not sure what

they did. I think he was in Italy for a while in the turmoil, when the Red Brigades

were active. But I don't know. {146)

In Falling Man, the presence of two characters-Martin and Nina-highlights

the epistemological ambiguity and fracture within Western culture that underlies alltcultural discourses on the reasons leading up to the events of September

11, 2001. On one side of the fray, we find Nina, who reads the violent clash

between cultures in terms of religious and cultural difference; on the other side,

we find Martin, who performs an analysis that subreptitiously addresses issues

of cultural and economic imperialism with their burden of structural violence:

"They strike a blow to this country's dominance. They achieve this, to show

how a great power can be vulnerable. A power that interferes, that occupies."

He spoke softly, looking into the carpet. "One side has the capital, the labor;,

the technology, the armies, the agencies, the cities, the laws, the police and the

prisons. The other side has a few men willing to die."

Grieving and Memory in DeLillo's Falling Man

47

"God is great," she said.

''Forget God. These are matters of history. This is politics and economics.

All rhe things that shape lives, millions of people, dispossessed, their lives, their

t:onsciousness." (46-7)

While Nina stubbornly clings to Giorgio Morandi's paintings as both icons of

Western civilization and a worldly projection of her own previous life~ Martin

suggests a more materialist reading of the political and intellectual reasons for

the terrorist attack.

3. Communication as Interior Reconciliation

In spite of the differences between DeLillo's characters in Falling Man, they all

share something in common: a deep and imperative need to come to terms

with the disappearance of an earlier, seemingly more secure and controlled

environment. Most of the novel's characters experience a symbolic coming to

awareness that has its source in the death of others, although Hammad~one

of the terrorists on the planes~interprets death as a way of completing the

one task that will ultimately give meaning to his life: "God's name on every

tongue throughout the countryside. There was no feeling like this ever in his

life. He wore a bo.mb vest and knew he was a man now, finally, ready to close

the distance to God" (172). In the intricate social puzzle that makes up DeLillo's

portrayal of human disarray, we meet a number of life stories that exemplify

the complex range of responses to emotional distress. In this novel, we encounter Hammad's Bildung as an inversion of the Western enlightened narrative

of the individual's sentimental education; the public performances of David

Janiak-the novel's eponymous figure---as a tribute to the memory of the lost

ones; and the children's confused reconstruction of the attack; their language

games and mispronunciation of Bin Laden's name ("BiH Lawton"). One way

or another, these characters and their survival strategies are both visually and

physically connected with the outside world-be it in the form of a book or a

painting, of a wall to climb or of a plane to look for in the sky.

Keith Neudecker's quest for inner reconciliation, however, proceeds along

somewhat different lines. He is a survivor from the North Tower ..vho witnessed, as we learn in the final chapter, the death of Rumsey, one of his closest

friends. Slightly injured, Keith wanders aimlessly for some hours and finally

ends up at his estranged family's place.

In contrast to Nina or Lianne, who partially retain a visual perception in

their need to redefine the role of tradition and remembrance in the elaboration

of grieving, in Keith's healing process, images are forcefully suppressed-at

times unsuccessfully-as they become a sort of obstacle impeding him from

moving on. Joseph Dewey stresses that:

[t]he problem, as DeLillo has articulated now across five decades of fiction, is

the loss of the authentic self after a half-century assault of images from film,

48

Terrorism, Media, and the Ethics of Fiction

television, tabloids, and advertising that have produced a shallow culture too

enamored of simulations, unable to respond to authentic emotional moments

without recourse to media models. (6)

In a culture that yearns for images, Falling Man is a mosaic made up from

interrelated histories where prefabricated images are basic starting points for a

deeper reflection on life in which memory and narrative are the main concepts.

In Dewey's yvords, "In the act of recording, in the precise engineering of prose,

the transient becomes stable; the inconsequential, significant; the neglected, the

examined" {10). Keith is lost in an outer cartography that he is unable to recognize and that does not display clear and known symbols of identification:

"The roar was still in the air, the buckling rumble of the fall. This was the

world now" (Delillo 2007, 3). Thus, this traumatized New York lawyer feels

the need to look meekly within himself and dive into an intimate process of

redefining subjectivity. Keith, it emerges, yearns to recuperate something that

really never existed-such as a close relationship with Lianne and his sonand he tries to fill the void in his soul by recovering sensations and emotions

which, in fact, never characterized his way of being:

It was Keith as well who was going slow, easing inward. He used to want to fly

out of self-awareness, day and night, a body in raw motion. Now he finds himself

drifting into spel!s of reflection, thinking not in dear units, hard and linked, but

only absorbing what comes, drawing things out of time and memory and into

some dim space that bears his collected experience. {66)

Keith is unable to connect with his new nightmarish perspective on reality and

he is trapped in an existential situation very close to psychological paralysis.

He rejects the relief images offer to make sense of what happened, and he

rejects images as a memory aid to redefine the past and give meaning to his

present even as he senses that he needs to do precisely that.

Keith's search for some kind of healing eventually revolves around two

activities: communication and playing poker, which in the context of his

present life story come to represent his connection with both the materiality of

life and a ceremonial perception of it. The conversations he has with Florence

Givens·, another survivor from the North tower, will soon become the nodal

point of his therapeutic path. Healing emerges as a possibility through words

and :t constant repetition of the events that links these two people. They share

a sense of closeness that nobody else can understand, and which will develop

into an intimate but transitory bond where speech finally transforms memories

into words that help both in handling nightmares and trauma:

They drank tea and talked. She talked about the tower, going over it again, claustrophobically, the smoke, the fold of bodies, and he understood that they could

talk about these things only with each other, in minute and dullest details, but it

would never be dull or too detailed because it was inside them now and because

he needed to hear what he'd lost in the tracings of memory. This was their pitch

Grieving and Memory in DeLillo's Falling Man

49

of delirium, the dazed reality they'd shared in the stairwells, the deep shafts of

spira!ing men and women. (91)

But the need to share his grief is not the only way Keith Neudecker tries to

overcome suffering. As I have indicated earlier, the game of poker is another of

Keith's strategies of survival and rebirth. Before the terrorist attacks, he played

poker once a week with a group of friends. This was a recurring event that

represented a steady point in his life, possibly the only one. After 9/11, he

invests in poker playing with an even stronger sense of rituality: the lost ritual

of the weekly game is now understood as a search for a new spirituality and a

new inner reality. By devoting his life to professional poker games-Keith 's

final election-he pays homage to all his poker mates that died in the attacks.

4. Conclusion

Despite the lingering presence of the images of the falling twin towers, visual

perception in Falling Man gradually recedes to make room for a group of

characters who do not try to find their place as individuals within a society

of spectacle. Instead, they struggle to embark on an introspective process to

recover their traumatized selves. After September 11, their old points of reference are shaken to the foundations. What results is a need to revise, analyze,

and recuperate personal histories and memories to escape ontological chaos. In

Dewey's words, which were written before the publication of Falling Man,

"most recently, [DeLillo] has turned to the implications of the soul, the difficult

confirmation of a viable spiritual dimension" (8). In his essay "In the Ruins of

the Future: Reflections on Terror and Loss in the Shadow of September" (2001),

DeLillo explains the role of the writer in relation to memory work after 9/11.

In a world transfigured by rage and terror, the writer's role is to give a voice to

those who cannot speak, to add a human dimension to desolation and wreck~

age: "The writer tries to give memory, tenderness, and meaning to all that

howling space" (39). And he adds, "There are a hundred thousand stories criss~

ctossing New York, Washington and the world[ ... ] Stories generating others

and people running north out of the rumbling smoke and ash {... ] and it is

precisely these stories that shape our response to the event" (34). The characters that people Falling Man are to some extent representative of what DeLillo

describes; each of them relies on his or her own survival strategies: culture,

politics, tradition, storytelling, language games, and a poker tournament. In

their own ways, they aim at recovering their old selves in a cartography that is

not recognizable anymore. These characters' narratives, nightmares, and obsessions highlight the need to recuperate and understand the past in order to face

the present. DeLillo writes that: "[t]he writer wants to understand what this

day has done to us" (39), but in the end, memories are all that is left: they are

the bridge that spans the past and the future.

50

Terrorism, Media, and the Ethics of Fiction

Notes

1. Kihlstrom's work is available online at socrates.berkeley.edu/-kihlstrrnlrmpaOO.

htm. See also Kihlstrom's essay in Proteus for a previously published version.

2. In The Human Condition, Arendt states: "The polis, properly speaking, is not the

city-state in its physical location; it is the organization of the people as it arises out

of acting and speaking together" (1998, 198).

Works Cited

Arendt, H. (1968). Men in Dark Times. New York: Harcourt, Brace and World.

~(1977), Between Past and Future. London: Penguin.

-(1998), The Human Condition. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Baer, U. (ed.) (2002), 110 Stories: New York Writes after September 11. New York:

New York University Press.

Berger, ]. (2005), "Falling towers and postmodern wild children: Oliver Sacks,

Don DeLillo, and turns against language." PMLA, 120,2: 341-61.

Best, S. {1995), The Politics of Historical Vision. New York: Guilford Press.

DeLillo, D. (2001), "In the ruins of the future: Reflections on terror and loss in the

shadow of September." Harper's Magazine, December, 33-40.

-(2007), Falling Man. New York: Scribner.

Dewey, ]. {2006), Between Grief and Nothing: A Reading of Don DeLillo. Columbia:

University of South Carolina Press.

Eakin, J. P. (2001). "Breaking rules: The consequences of self-narration." Biography,

24.L 113-27.

Houen, A. (2004), "Novel spaces and taking place(s) in the wake of September 11."

Studies in the Novel, 36, 3: 419-37.

Kihlstrom, J. F. (2002), "Memory, autobiography, history." Proteus: A Journal of Ideas,

19, 6' 1-6.

-{2009), Memory, Autobiograph}~ History. University of California, Berkeley.

socrates.b erk el ey.ed u/-kihlstrrnl rm paO 0 .htm.

Kohn,J. (1977), "Introduction," in Between Past and Future, by Hanna Arendt, vii-xxii.

London: Penguin.

Kubiak, A. (2004), "Spelling it out: Narrative typologies of terror." Studies in the Novel,

36, 3, 294-301.

Longmuir, A. (2005), "The language of history: Don DeLillo's The Names and the

Iranian hostage crisis." Critique, 46,2: 105-20.

Tew, P. (2007), The Contemporary British Novel. London: Continuum.

Wilstm, S. (1995), Cultural Materialism: Theory and Practice. Oxford: Blackwell.