ALASKA’S UNIQUE CIVIL RIGHTS STRUGGLE

advertisement

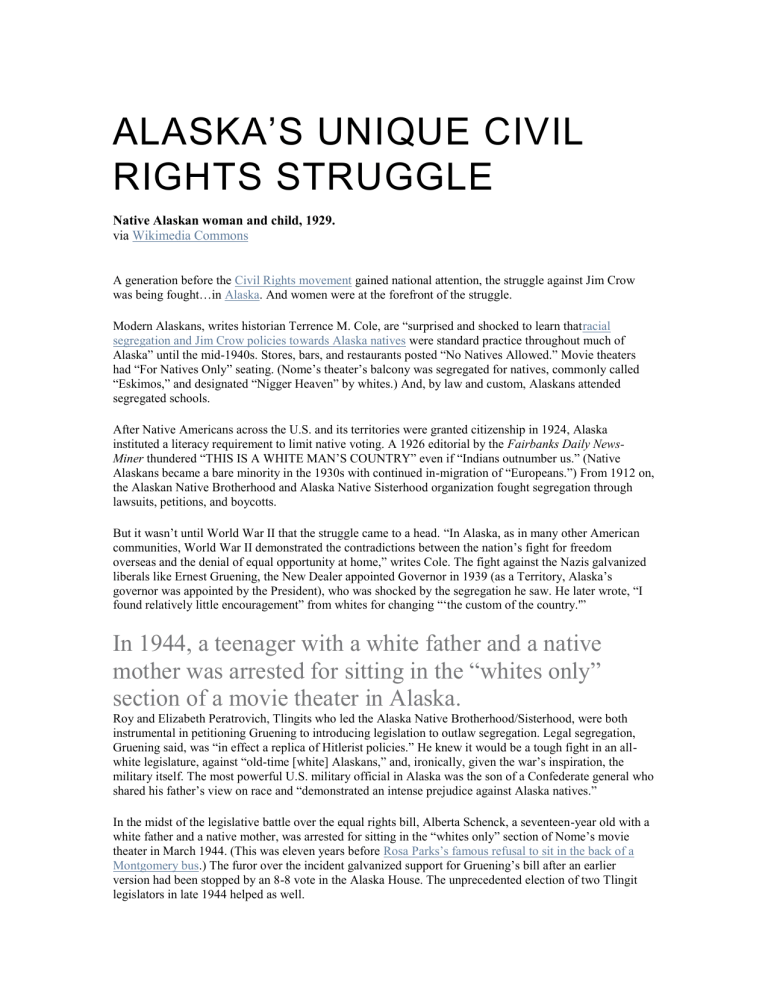

ALASKA’S UNIQUE CIVIL RIGHTS STRUGGLE Native Alaskan woman and child, 1929. via Wikimedia Commons A generation before the Civil Rights movement gained national attention, the struggle against Jim Crow was being fought…in Alaska. And women were at the forefront of the struggle. Modern Alaskans, writes historian Terrence M. Cole, are “surprised and shocked to learn thatracial segregation and Jim Crow policies towards Alaska natives were standard practice throughout much of Alaska” until the mid-1940s. Stores, bars, and restaurants posted “No Natives Allowed.” Movie theaters had “For Natives Only” seating. (Nome’s theater’s balcony was segregated for natives, commonly called “Eskimos,” and designated “Nigger Heaven” by whites.) And, by law and custom, Alaskans attended segregated schools. After Native Americans across the U.S. and its territories were granted citizenship in 1924, Alaska instituted a literacy requirement to limit native voting. A 1926 editorial by the Fairbanks Daily NewsMiner thundered “THIS IS A WHITE MAN’S COUNTRY” even if “Indians outnumber us.” (Native Alaskans became a bare minority in the 1930s with continued in-migration of “Europeans.”) From 1912 on, the Alaskan Native Brotherhood and Alaska Native Sisterhood organization fought segregation through lawsuits, petitions, and boycotts. But it wasn’t until World War II that the struggle came to a head. “In Alaska, as in many other American communities, World War II demonstrated the contradictions between the nation’s fight for freedom overseas and the denial of equal opportunity at home,” writes Cole. The fight against the Nazis galvanized liberals like Ernest Gruening, the New Dealer appointed Governor in 1939 (as a Territory, Alaska’s governor was appointed by the President), who was shocked by the segregation he saw. He later wrote, “I found relatively little encouragement” from whites for changing “‘the custom of the country.'” In 1944, a teenager with a white father and a native mother was arrested for sitting in the “whites only” section of a movie theater in Alaska. Roy and Elizabeth Peratrovich, Tlingits who led the Alaska Native Brotherhood/Sisterhood, were both instrumental in petitioning Gruening to introducing legislation to outlaw segregation. Legal segregation, Gruening said, was “in effect a replica of Hitlerist policies.” He knew it would be a tough fight in an allwhite legislature, against “old-time [white] Alaskans,” and, ironically, given the war’s inspiration, the military itself. The most powerful U.S. military official in Alaska was the son of a Confederate general who shared his father’s view on race and “demonstrated an intense prejudice against Alaska natives.” In the midst of the legislative battle over the equal rights bill, Alberta Schenck, a seventeen-year old with a white father and a native mother, was arrested for sitting in the “whites only” section of Nome’s movie theater in March 1944. (This was eleven years before Rosa Parks’s famous refusal to sit in the back of a Montgomery bus.) The furor over the incident galvanized support for Gruening’s bill after an earlier version had been stopped by an 8-8 vote in the Alaska House. The unprecedented election of two Tlingit legislators in late 1944 helped as well. But it was Elizabeth Peratrovich’s moving testimony for the bill that many credit for its passage. Elizabeth and her husband Roy turned to activism after moving to Juneau in 1941 and witnessing the horrible treatment of Native Alaskans there. Peratrovich had an answer for all the white senators who said laws would not stop racial discrimination. She noted that laws against murder and larceny didn’t necessarily stop those things, either, but this didn’t mean there should not be laws against them. The act was signed into law on February 6, 1945. February 6 is now honored as Elizabeth Peratrovich Day in Alaska. The passage of the Alaska Equal Rights Act of 1945, fourteen years before statehood, and nearly two decades before the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964, did not, of course, end discrimination. But it made discrimination illegal for the first time in the United States, and set an important precedent for all future anti-discrimination laws.