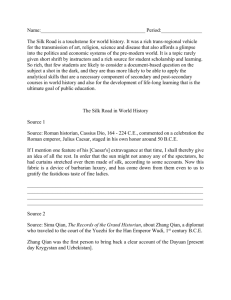

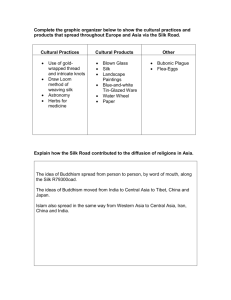

The Silk Road in World History (Suggested writing time – 40 minutes) You should spend at least 10 minutes reading, analyzing, and grouping the sources. Directions: The following question is based on the accompanying Documents 16. (The documents have been edited for the purpose of this exercise.) Write your answer on the lined pages of the Section II free-response booklet. This question is designed to test your ability to work with and understand historical documents. Write an essay that: Has a relevant thesis and supports that thesis with evidence from the documents. Uses all of the documents. Analyzes the documents by grouping them in as many appropriate ways as possible. Does not simply summarize the documents individually. Takes into account the sources of the documents and analyzes the authors’ points of view. Identifies and explains the need for at least one additional type of document. You may refer to relevant historical information not mentioned in the documents. Question: To what extent did the Silk Road create an interconnected network? Identify an additional type of document and explain how it would help your analysis of the Silk Road in creating interconnected network from the 2nd century C.E. to the 13th century? Historical Background: The Silk Road is an ancient network of trade and cultural transmission routes that were central to cultural interaction through regions of the Asian continent connecting the West and East by merchants, pilgrims, monks, soldiers, nomads and urban dwellers from China and India to the Mediterranean Sea from the second century C.E. to the 13th Century C.E. The Silk Road is a touchstone for world history. It was a rich trans-regional vehicle for the transmission of art, religion, science and disease that also affords a glimpse into the politics and economic systems of the pre-modern world. Document 1 Source: Roman historian, Cassius Dio, 164 - 224 C.E., commented on a celebration the Roman emperor, Julius Caesar, staged in his own honor around 50 B.C.E. If I mention one feature of his [Caesar's] extravagance at that time, I shall thereby give an idea of all the rest. In order that the sun might not annoy any of the spectators, he had curtains stretched over them made of silk, according to some accounts. Now this fabric is a device of barbarian luxury, and has come down from them even to us to gratify the fastidious taste of fine ladies. Document 2 Source: Sima Qian, The Records of the Grand Historian, about Zhang Qian, a diplomat who traveled to the court of the Yuezhi for the Han Emperor Wudi, 1st century B.C.E. Zhang Qian was the first person to bring back a clear account of the Dayuan [present day Krygystan and Uzbekistan]. Anzi [Parthian Persia] is situated several thousand li [a little more than a third of a mile] west of the region of the Great Yuezhi. The people are settled on the land, cultivating the fields and growing rice and wheat. They also make wine out of grapes. .... Document 3 Source: Anonymous assistant to a Chinese merchant, A Record of Musings On the Eastern Capital, about Hangzhou, capital of the Southern Sung Dynasty, 1235. During the morning hours, markets extend from Tranquility Gate of the palace all the way to the north and south sides of the New Boulevard. Here we find pearl, jade, talismans, exotic plants and fruits, seasonal catches from the sea, wild game -- all the rarities of the world seem to be gathered here. Some of the hustlers are students who failed to achieve any literary distinction. Though able to read and write, and play musical instruments and chess, they are not highly skilled in any art. They end up being a kind of guide for young men from wealthy families, accompanying them in their pleasure-seeking activities. Document 4 Source: Faxian, A Chinese Buddhist Monk's Travels in India and Ceylon, 399 - 411 C.E. From this place [Central Asia], we traveled southeast, passing by a succession of very many monasteries, with a multitude of monks .... When stranger monks arrive at any monastery, the old residents meet and receive them .... Document 5 Source: Friar John of Monte Corvino, Letter to the West, one of two letters written to his fellow Franciscans around 1295. John was sent by Pope Nicolas IV to try to make an alliance with the Mongols against the Mamluk rulers of Egypt. I, Friar John of Monte Corvino, of the Order of Friars Minor, departed from Tauris, a city of the Persians, in the year of the Lord 1291, and proceeded to India. And I remained in the country of India, wherein stands the church of St. Thomas the Apostle, for thirteen months, .... I proceeded on my further journey and made my way to Cathay, the realm of the emperor of the Mongols who is called the Great Khan. To him I presented the letter of our lord the pope, and invited him to adopt the Catholic faith of our Lord Jesus Christ, but he had grown too old in idolatry. However he bestows kindnesses upon the Christians, and these two years past I am abiding with him. Document 6 Source: Marco Polo, The Travels of Marco Polo, a Venetian merchant who may have worked for the Yuan dynasty, the Mongol rulers of China, late 13th century. This excerpt is a description of Hangzhou, a southern city that was part of the Yuan empire. There are within the city ten principal squares or market places, besides innumerable shops along the streets. .... On the nearer bank ... stand large stone warehouses provided for merchants who arrive from India and other parts with their goods and effects. They are thus situated conveniently close to the market squares. In each of these, three days in every week, from forty to fifty thousand persons come to these markets and supply them with every article that could be desired.