controlling the housing land market- some examples from europe. pdf

advertisement

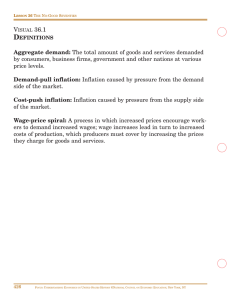

Urban Studies, Vol. 30, No. 7, 1993 1 129-1149 Controlling the Housing Land Market : Some Examples from Europe James Barlow [Paper first received, July 1991 ; in final form, June 19921 Summary . One major problem for the production of low-cost housing in the UK is the continued lack of control over the market for housing land, yet there is very little debate about ways of controlling land prices. This paper assesses some alternative approaches to land-use planning by focusing on high growth sub-regions in Britain, France and Sweden . It examines the flexibility of these planning systems to changes in the demand for housing land and the relationship between land release, land prices and house prices. The paper argues that the British approach is subject to a high level of uncertainty, exacerbating risk-taking speculative behaviour and price inflation . Under the French system, development uncertainty is reduced and house prices more rigidly controlled, with the result that speculative behaviour is constrained . The Swedish system is dependent on the ability of local authorities to build up land reserves which act as a buffer against price inflation . However, pressure on land prices in the open market has made this approach increasingly hard to sustain . Introduction Although there is a voluminous literature on the relationship between the planning system, land supply, land and house prices, much of the debate founders on definitional confusions and the extreme simplification of complicated real-world relationships . In a recent comprehensive survey of the debate, Monk et al. (1991) argue that this literature tends to neglect the distinction between land made available for housing by the planning system and land defined as available under economic theory . While it may be possible for a planning system to impose absolute control on land supply, supply is not fixed in the long run because land can be converted from alternative uses and the amount used in the production of each dwelling can be increased or decreased . How fixed land supply ultimately is depends on the way time is treated in the theory, although `time` is never actually defined in the literature. Monk et al. also argue that explanations which are grounded in `comparative statics', i.e . the joint determination of land use and land price, modelled in terms of a trade-off between job and market accessibility in city centres and the consumption of space, are unsatisfactory because they simplify reality to an extreme degree . Many relationships are not fully specified and the more actual behaviour is incorporated, the more these models lose generality and predictive power . There are major gaps in the ability of comparative statics to handle the relationship between new and existing house prices, monopoly landownership, speculative be- James Barlow is at the Policy Studies Institute, 100 Park Village East, London NW/ 3SR, UK . 1129 Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at RICE UNIV on May 21, 2015 1 130 JAMES BARLOW haviour, lags, expectations and risk . On the other hand, the `behavioural' literature is essentially untheorised, although it has provided useful insights into local variations in housing and land markets, planning condevelopers' knowledge, and straints, landowners' motives . A third approach, the `structural' view, emphasises the distributional struggle between landowners and developers within the context of a changing framework of housing provision. In the long run, Monk et al. argue, this approach actually draws similar conclusions to the comparative statics position inasmuch that it sees the interrelationship of house prices, building costs, output and unstable demand as resulting in inflationary pressures . This assessment of the existing research has three implications : (1) It is important to define what is actually meant by the short and long run, since the fixity of land supply is likely to be variable over time . (2) It is important to take into account differences in the behaviour of landowners and developers, since non-rational expectations and risk-minimising strategies clearly play a significant part in the development process. (3) It is necessary to accept that there are local variations in the operation of housing and land markets, as these are spatially bounded and local planning authorities frequently operate with a degree of autonomy and discretion . All this suggests that any empirical analysis needs to be clear about the parameters set by the structure of housing provision as a whole and their evolution over time (cf . Ball et al., 1988) . This evolution does not result in some long-run equilibrium state (or series of equilibria) . Rather, it takes the form of continuous change in institutional forms and state-market relationships . An understanding of the structure of housing provision also allows a better integration of speculative risk-taking behaviour as it emphasises the strategies of the various parties involved in the development process . The objective of this paper is to investigate some of these issues by using a crossnational comparative approach . Its focus is on the relationship between the planning system, land supply and land prices, rather than the long-run relationship between the supply of new housing and house prices. The aim is to illustrate some of the potential ways in which alternative systems of regulating land supply influence land availability and prices and illustrate the importance of understanding long- and short-run change in the context of the wider structure of housing provision . As an acid test, the performance of three contrasting planning systems-those of the UK, France and Sweden-is examined in high-growth housing and labour market areas . High-growth areas have been chosen because it is here that the pace of change, both in housing demand and supply, is dramatic . The process of economic restructuring often brings new workers into the area rather than simply re-employing those in existing jobs, leading to changes in housing demand which may be disproportionately greater than the employment growth . The logic for choosing France and Sweden as examples of different policy frameworks is that these countries provide highly contrasting approaches to development control and land-use planning, as the next section shows . Planning and Development Systems : The National Framework Alternative Regulatory Systems There are major differences in European planning systems . These shape the ways in which housing is provided and the competitive strategies of developers and landowners . The British planning system is perhaps distinguished by the fact that it has become increasingly politicised in recent years, making it subject to a high degree of uncertainty . This arises from the fact that developers have no automatic right of development, as tends to be the case under a zoning system, while local authorities have considerable discretion in the way they operate development control . Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at RICE UNIV on May 21, 2015 CONTROLLING THE HOUSING LAND MARKET The implementation of land allocation policies can therefore vary considerably between authorities . Attempts in the early 1980s to make the system more flexible for developers ran up against a growing tide of protest by residents in some areas, and the latest legislation (the Planning and Compensation Act 1991) moves the system back to `firmer' planning, possibly heralding greater certainty in the development process (Mynors, 1991) . The housebuilding industry has historically had a favoured status in France . The finance system emphasises investment in new housing, with a range of reduced interest loans available to purchasers and investors . Although conditions limiting household income, dwelling size and house price are attached to these loans, they have tended to stimulate new construction . The planning system also favours new development . While public consultation during the preparation of a plan d'occupation du sol (POS) or local plan is mandatory, there is comparatively little opportunity for third parties to object to its content. A POS is only legally required in communes of over 10 000 inhabitants, although most have adopted local plans voluntarily . The system of zoning means that detailed local plans essentially comprise a legally-binding document containing the right to develop . However, compared to the UK the system of local government is highly fragmented and the decentralisation of political power in 1982 increased the role played by local mayors in the granting of development permits . Although local conditions vary, with communes under right-wing control having a reputation for refusing planning permission for low-cost housing development, the system is such that developers can be fairly certain of obtaining a building permit providing their scheme fits in with the zoning requirements . In general, planning permission is rarely refused ; developers' plans are simply modified. The zoning requirements are not, in any case, always crucial to the outcome of a planning application since large areas of the countryside (as well as urban areas) are left unzoned . Although planning permission only lasts four 1131 years and the POS can change following local elections (which take place every six years), development control is potentially more flexible and responsive to housebuilders' demands than in Britain . In addition, the Programme d'Action Fonciere from the mid 1970s to 1984 enabled communes in major conurbations to use low-interest loans to buy land for their future development needs . The key point about the Swedish approach is that supply of new housing is subject to a high degree of state control (Duncan, 1989), (although the Swedish system is now undergoing considerable change following the election of a Conservative-dominated coalition in 1991) . In effect, a system of reduced-interest state housebuilding loans (SHL) precludes speculative housebuilding on British lines, although this is not to say that speculative pressures or behaviour are absent. Under the SHL system, land and construction costs are subject to controls, while the `land condition' (markvillkoret) insulates housing land from the overall land market. The markvillkoret requires that all housing built with an SHL-except for individually-built, one-off, single-family dwellings and housing built under certain other special circumstances-must use land from commune land banks. Nationally, around 70 per cent of new housing is built on commune land, although almost all housing is built with an SHL . Most of the remainder uses land which, although not owned by communes, is licensed by them and has similar price/quality parameters . Developer Strategies These differences in the way housebuilding is regulated are partly responsible for shaping the competitive strategies of the development industry (Barlow and King, 1992 ; Barlow, 1992). It is important to stress that in many countries the bulk of new housing is promoted by non-profit or limitedprofit agencies, or by individual households (`self-promotion'). Speculative development is relatively rare in France and almost non- Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at RICE UNIV on May 21, 2015 1 13 2 JAMES BARLOW existent in Sweden . In Great Britain, however, around 80 per cent of total completions are now by speculative developers, compared to 40 per cent in France. Although 90 per cent of total Swedish housing completions are built by profit-making construction companies, these firms only promote about 30 per cent of the total . The remainder are built under contract for co-operatives or commune-controlled housing companies . Almost all the dwellings promoted by private developers are built with SHLs and hence speculative strategies are precluded . Selfpromoted housing accounts for around half the annual output in France and over 20 per cent of the Swedish output, compared to 5-6 per cent in the UK. Differences in the way the state intervenes in the land market, mainly through the planning process and taxation, mean that housebuilders cannot compete in the same way in each country . The British system means that access to land and the ability to build up landbanks is of paramount importance (Ball, 1983). Housebuilders, attempt to increase their development profits by maximising the difference between land and house prices . This does not mean that firms are simply concerned with land speculation . Clearly, until housing is built and sold the development value of the land cannot be capitalised . However, skills in land purchase and timing completions to maximise gains from house price inflation tend to be more important than the ability to compete through technical innovation. In contrast, land plays a rather different role for developers in France and Sweden . Although a private land market exists in Sweden, the SHL system and public landownership largely preclude the landoriented strategies adopted by British developers . In France, developers are superficially similar to their British counterparts . However, these firms tend to buy land for their immediate use, rather than purchasing longer-term strategic land . This is partly because of relatively low land price inflation (in most areas) and partly because land holding taxes are levied if development does not take place within a certain period after purchase . However, we should recall that over half the annual French housebuilding level is 'selfpromoted' . This system is dominated by specialist builders-who build the housingand lotisseurs, specialist land assembly firms . The builders do not speculate in the land market since they are currently forbidden from owning land (see Barlow, 1992). Since `playing' the land market is less important for Swedish and French developers, firms in these countries have adopted a range of alternative competitive strategies, involving technical innovation and improvements in product quality . Some Implications for Housing Land Supply The differences in planning mechanisms and developers' competitive strategies suggest that the operation of the housing land market is likely to be rather different in the UK, France and Sweden . In the UK, the level of uncertainty in the planning process increases the risk level for developers, but equally the lack of fiscal control over an historically inflationary land market allows them to achieve potentially high (albeit unstable) profits. However, because of the historically high land price inflation and the possibility of overturning local planning decisions by appeal, landowners' expectations are likely to be high, resulting in an unwillingness to drop prices except under the most financially straightened circumstances . This relationship between landowners and developers operates within a framework characterised by a ,higher degree of local planning discretion than in some other countries . Hence, the responsiveness of the planning system to increased demand for land is likely to be variable at the local level . The French planning system potentially affords more certainty for developers, although this is also subject to local variations, with planning decisions dependent partly on the political complexion of the specific commune . Nevertheless, the zoning system means that land supply may be more flexible in the short term in that it is able to respond Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at RICE UNIV on May 21, 2015 CONTROLLING THE HOUSING LAND MARKET to immediate changes in the demand for development land . Taxation of land holding and lower rates of inflation mean, however, that landowners and developers have lower expectations and developers tend to adopt a less land-oriented competitive strategy than their British counterparts . The Swedish system stands in complete contrast to those of the UK and France. Here, local authorities play a major role in the land market, buying open market land at preemption prices for their land banks. The bulk of housing development occurs on this land . The scope for speculative activity by landowners and developers is therefore limited. In short, the parameters of the land supply and demand equation are shaped by the operations of local authorities in the land market. This means that there is potentially a closer match between supply and housing need, since local authorities can release land for development according to the requirements of their local housing plans . However, this is likely to depend on the extent of the public landbank in a given commune and local political attitudes to development . Furthermore, it is quite possible (as developers argue) that while housing needs are fulfilled by this system, some effective housing demand is being excluded and more dwellings could be brought to the market in the absence of such controls . Do these differences in regulatory form also imply differences in flexibility over time? The British system of structure and local planning is heavily reliant on the ability of local authorities to identify land requirements for a number of years in advance ; hence it is subject to competing claims over the likely rate of population and employment growth and the definition of suitable housing land. In the short run, the system may be sufficiently flexible to respond to immediate demands for land, providing this land has already been identified as suitable . However, during the 1980s, the system increasingly ran up against disputes over the best techniques for forecasting land requirements (see Hooper et al., 1989), as well as anti-development pressure from local residents' groups . 1133 The longei-term evolution of the planning system over the 1980s may have therefore removed some of its flexibility as it became increasingly exposed to competing political forces. Although the POS system requires French communes to identify future land availability, zoning offers a more immediate response to the changing demand for land because of the embodied right to develop and lack of third party protest rights . This is not to suggest that local political battles over land availability do not occur (especially in areas of development pressure) and that there has not been lobbying by developers at a national level . Rather, the French approach implies a more immediate, short-term flexibility . The Swedish system is altogether different . Here, control over housing land markets is geared towards the fulfilment of housing needs rather than the demand for land from developers. Essentially, the housing system is insulated from market forces to a greater degree than in the UK or France. This makes the concept of `effective demand' for housing less meaningful than in those countries . While Swedish developers argue that the potential demand for owner-occupier houses is not being effectively met, the altogether different approach to housing provision undermines the premises on which this argument is based . Distinctions between short and long run flexibility are therefore less valid than in other countries . In order to capture the effects of changing demand for housebuilding land, this paper examines the housing and land markets of the case-study areas during the 1980s . This was an important period in all three countries because the property sector in each was subject to a complete boom and slump cycle (to a greater or lesser degree) . As argued above, in the long run, even under under stringent planning conditions, land supply is responsive to changing demand . Pressure to increase land supply is often exerted through lobbying of central government, ar14 the planning system is subjected to long-term evolution . This was the case in the UK in the early 1980s and in France in mid 1980s, and Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at RICE UNIV on May 21, 2015 1 13 4 JAMES BARLOW has been the case in Sweden since the late several sources . There is only limited information on land prices in the Paris case-study 1980s. However, the long run at a `macro' or area, and the data were based on studies for `national' scale may be irrelevant when deal- the ddpartement of Essonne (Vilmin, 1987), ing with local labour/housing market areas . interviews with developers and data provided This is because land and dwellings are essen- by the Direction Department de L'Equipetially non-substitutable at this scale since ment. Toulouse is much better researched housing demand is largely expressed within and the AUAT (Agence d'Urbanisme de specific local labour/housing markets . In ad- l' Agglom-eration Toulousaine) provides a dition, smaller areas tend to be more subject time series for different types of housing land to `local' political and economic factors for the metropolitan area (see Figure 1) . while national indicators tend to smooth over One problem with comparing housing land local variations . This is important in the case price statistics is the basis on which they are of land supply, since local lobbying for and collected. In the UK, the DoE figures are for against development is likely to be more a hectare of land sold for all forms of housextreme-it is easier to organise ; local gov- ing development, including apartments (the ernment and the local political framework is limited amount of apartment construction in more prone to pressure from special-interest the UK means that we can discount the effect groups'-hence there is a greater impact on of this on average land prices). The French land supply than at the national level . data are separated into land for self-promoted Finally, the importance of the supply of new housing (with land prices on a plot basis) and housing units in relation to the overall stock prices per m2 of land for apartments. The of housing will be more significant at the Swedish data are for land for houses, mealocal level . All these factors therefore point sured in terms of the average price of each to the need to analyse the relationship be- transaction and the average transaction size tween the planning system and land supply at in m2. In the analysis which follows, we have a local level . Before turning to the case used land data for houses rather than apartstudies, however, it is first necessary to con- ments for ease of comparison. It should be sider problems of data availability and noted that the construction of houses is concomparability . siderably less important than apartments in the E4 Corridor, accounting for 40 per cent Data Problems of completions in the 1980s . Information on land markets is notoriously A further problem for making accurate hard to interpret, even assuming sufficient comparison is the fact that the French and data can be obtained in the first place . The Swedish data are for `raw' housing land plus housing land price series used here were basic infrastructure . This is not the case for derived from a number of sources and are as the DoE series . The cost of infrastructure is comparable as possible . The Swedish data thought to increase the basic land cost by c . were provided by the national statistical bu- 45 per cent in the UK (see Conran Roche, reau (SCB), which was able to create special 1989). tabulations specifically for the nine caseSince 1981, the DoE has published two study communes (see Figure 1) . This series on the housing land market, one more information was supplemented by interviews widely based than the other . What is termed with planners and developers. For the UK, here the `narrow series' (Table 10 .1 in the we used the DoE's housing land price series . annual DoE Housing and Construction The DoE was able to provide data Statistics) is restricted to sites with planning specifically for Berkshire (Figure 1) and permission and covers only sites which are again this information was supplemented by used to create the DoE's land price index . interviews with planners and developers. Fi- The `wide series' (Table 10 .2) includes sites nally, the French data were assembled from without planning permission but which are Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at RICE UNIV on May 21, 2015 CONTROLLING THE HOUSING LAND MARKET 1135 Ile de France Region •••••••••• Department boundary Midi - Pyrenees Region Department boundary Stockholm County •- - -- = # ii= Stockholm Metropolitan Area Commune Boundary -at= Uppsala or Legend for all maps ® Economic Growth Zone an dHousing Impac t Z one Housing Impact Zone Figure 1 . The case-study areas : the South Paris growth area (top left) ; the Toulouse metropolitan region (top right) ; Berkshire and the M-4 Corridor (bottom left) ; and the E4 communes in the Stockholm region (bottom right) . Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at RICE UNIV on May 21, 2015 1 136 JAMES BARLOW known to be destined for housebuilding . One important limitation of both series is that only larger purchases of land, i .e . sites with four or more plots, are covered . Each series provides information on the amount of land sold-i .e . total area, number of transactions and number of plots-and its price . According to the DoE, the narrow series provides a better long-term indicator of price trends while the wider series provides better coverage of the market in any given year . The price series for Toulouse have been derived from AUAT data on prices per plot for 'self-promoted' houses . Using AUAT data we have also produced average prices for developer-built houses . Land prices in South Paris have been estimated from Vilmin's study of three communes (Vilmin, 1987), weighted according to the number of housing completions in each commune (for 1980-84), and data provided by the Direction Ddpartemental de l'Eyuipement for 48 communes, similarly weighted (for 1989) . The E4 Corridor series have been estimated from the land price per m2, weighted according to the number of transactions in each commune . The Planning System and the Land Market in Four Boom Areas Housing Development and the Planning Framework Berkshire, Toulouse, South Paris and the `E4 Corridor' north of Stockholm (see Figure 1) were selected as case-study areas because they had each experienced considerable employment growth, based on similar economic sectors, during the 1980s . Average household income levels were relatively close, thereby minimising the effect of wide divergences in disposable income on housing expenditure . In order to delimit a suitable case-study area, we initially identified an `economic impact zone' of maximum employment growth and then attempted to establish a `housing impact zone' based on commuting patterns . Full details of the selection process and the case-study areas themselves can be found in Barlow and Duncan (1992) . Briefly, each area saw the construction of large amounts of new housing during the 1980s and their housing markets remained relatively buoyant throughout the decade . In Berkshire new construction averaged approximately 5000 dwellings per annum for much of the 1980s and new housing accounted for about 21 per cent of the 14 000 dwellings traded in the county in any given year. The French examples were also extremely buoyant. South Paris, encompasing the northern part of the departements of Essonne and Yvelines, was one of the region's key areas of economic and population growth during the 1980s . Annual housing completion rates averaged 6000-7000 dwellings during the 1980s . Toulouse was also an extremely dynamic growth area . Here, total completions grew from under 4000 in 1980 to almost 7000 in 1988 . Finally, in the E4 Corridor, stretching from the northern suburbs of Stockholm to Arlanda Airport, annual completions during the 1980s averaged 20004000 units . On a per capita basis, this was considerably higher than the other case-study areas . While crude housebuilding levels were high in all four areas, the part played by different types of developer varied considerably . Private speculative developersbuilding for owner-occupation-were always dominant in Berkshire, but their share of completions grew from around 65 per cent to 90 per cent over the decade . Local authority and housing association completions fell from about 35 per cent to 10 per cent over the same period . Housebuilding in South Paris was also dominated by speculative developers, who accounted for 46 per cent of the output during the 1980s . The market share of lotissement housing (where plots are assembled by speculative purchasers but dwellings built for individual households by specialist companies) fell from a peak of 24 per cent in 1986 to 14 .8 per cent in 1989 and social housing agencies (HLMs) played an increasingly marginal role . Most of the few housing in South Paris was therefore built by speculative developers for owner-occupation . In contrast, until 1986 half the total com- Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at RICE UNIV on May 21, 2015 CONTROLLING THE HOUSING LAND MARKET pletions in Toulouse were in the lotissement sector, although this level has now fallen to a quarter . Most of the balance has been taken up by speculative development . However, while private housebuilders are dominant in both French case-study areas, much of the new construction is `regulated' via the financial subsidy system . In South Paris, 45 per cent of completions in 1987-89 were built for the PAP/PLA marketpret a 1'accession a la propriete (subsidised housing for lower-income purchasers) and pret locatif aide (subsidised housing for lowerincome tenants)-and a further 26 per cent for the PC marketpret conventions (subsidised housing for middle-income purchasers). In Toulouse, the output of regulated housing is higher : during the 1980s about 58 per cent of new completions were in the PAP/PLA sectors . While most of the output was for sale to owner-occupiers or private investors (for subsequent renting), HLMs providing housing for social renting have also remained an important force, accounting for 15-25 per cent of annual completions . Finally, in the E4 Corridor, completions by commune housing companies (for affordable renting) remained relatively steady at around 40 per cent of total output during the 1980s. For the balance, however, there was a striking realignment between different types of developer : the share of private-sector developers building for owner-occupation or private renting collapsed from about 40 per cent to 10 per cent between the early and late 1980s; co-operatives (building for a form of shared-ownership) increased their share from 15 per cent to 40 per cent . 'Self-promotion' accounted for the remainder, growing from about 10 per cent to 15 per cent . The structure of local government also varies considerably between the case-study areas . The French examples are fragmented into a large number of small communes, each with considerable autonomy to make decisions on planning applications . The Toulouse metropolitan area (total population 605 000 in 1988) is dominated by Toulouse itself (with a population of 350 000) and is subdivided into a further 61 communes . There is 1137 relatively little co-ordination in planning between the various municipalities. South Paris (with a population of 1 735 000 in 1990) comprises 82 communes in total . These fall into three distinct sub-markets consisting of two new towns (Evry and St. Quinten-enYvelines) and a large undeveloped area subject to considerable development pressure . There is some co-ordination at the regional level, but in general each commune has a high degree of autonomy . Berkshire (total population 718 000 in 1989) comprises a county council, responsible for broad strategic planning, and six local authorities, responsible for the day-to-day administration of planning applications and the formulation of local plans . One characteristic feature of Berkshire over the last 20 years has been the fact that development pressure has been channelled into the county because surrounding counties have exercised restraint policies . Finally, the E4 Corridor (population 387 000 in 1987) comprises nine communes . Local authorities in Sweden have a far higher level of political autonomy and considerable fiscal powers (Elander and Montin, 1990) . This includes the ability to purchase land for public land banks for housing development and an obligation to formulate local five-year housing plans. While this is the case in the E4 Corridor, to some extent policies established at a metropolitan level have set the broad parameters for housing development during the mid to late 1980s . In 1986, a Housing Delegation (Bostadsdelegation) was set up by national government to tackle the housing shortage perceived in Stockholm County . Stockholm County covers the Stockholm metropolitan region including the E4 Corridor-(see Figure 1 .) In order to shift the emphasis from commercial to residential development, this recommended an overall limit to commercial building (set at 70 per cent of 1986 levels) and that there should be a 1 :1 balance between office development space and housing space . A 10 per cent tax on investment in commercial building in the area was later imposed and subsequently raised to 30 per cent in 1990 . Other com- Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at RICE UNIV on May 21, 2015 1 13 8 JAMES BARLOW Table 1 . Land price per m 2 of housing space (£ per m2 converted at purchasing power parity) Year E4 Corridor' Berkshireb Toulouse South Parisd 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 55 56 64 62 66 66 64 99 126 152 118 98 118 132 206 169 242 370 - 105 105 121 112 122 138 148 204 236 248 254 268 375 409 ' E4 Corridor represents the land cost for houses built under the SHL system . Assumes average plot size of 600 m2 . Average dwelling sizes have been derived from data provided by SCB . b Berkshire data include some land for apartments, therefore average is likely to be overestimated . Data from DoE special tabulation, mean land prices for `wide' series . Average dwelling size from Nationwide Building Society data; average plot size estimated from DoE data on plots/ha (see text) . ` Toulouse estimates are for lotissement sector houses . Figures assume a dwelling of 115 m2 . Plot size from AUAT data . d South Paris estimates are for lotissement sector houses . Average dwelling size estimated from GRECAM data (1980-84 : 117 m2 ; 1986: 99m2 ; 1988-89 : 114 m2 ) . Assumes a 550 m2 plot . mentators (LSL, 1989) called for the encouragement of a freer property market which, it was claimed, would restore profitability to private housebuilding and boost completion rates . There have now been moves in this direction . Having discussed the broad features of each case-study area, we will now consider their land markets . The next section exammines the land price trends during the 1980s and the relationship between planning, land supply and land and house prices inflation . Land Price Trends Table 1 compared the absolute price per m 2 of land for houses, converted into sterling at purchasing parity . The table shows the actual land price element for houses-i .e . the price per m2 of housing space . While a number of assumptions have been made in drawing up this table (see notes to table), it provides as accurate as possible an indication of the absolute price differences in each case-study area. Some qualifications should, however, be made when interpreting the figures . The prices are actual prices per m 2 of housing space, and are not standardised to take into account differences in plot and dwelling size . Houses in South Paris and Toulouse tend to be larger than those in Berkshire and, more significantly, plot sizes are larger . The extremely high price of housing land in Berkshire and South Paris can easily be seen from this table . At around £400 per m 2 in 1988, land in these areas is about three times as expensive as its equivalent in the E4 Corridor . Prices in Toulouse were generally slightly higher than the E4 Corridor. Because of the differences in average dwelling and plot size between each casestudy area, we have recalculated these land prices assuming the dwellings are a 'standard' Berkshire new house (dwelling size: 99 m2 ; plot size : 374 m2) . These i have been estimated using data from the DoE on the average number of plots per hectare on land sold in Berkshire and data from the Nation- Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at RICE UNIV on May 21, 2015 1139 CONTROLLING THE HOUSING LAND MARKET Table 2. Land price per m2 of housing space, `standard' Berkshire dwelling (dwelling size : 99 m2; plot size : 374 m ), £ per m 2 converted at purchasing power parity Year 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 Source : E4 Corridor 39 49 43 47 46 47 61 78 95 110 Berkshire Toulouse 117 117 155 177 225 283 365 648 70 71 79 81 85 95 104 South Paris 162 186 195 201 211 296 323 derived from Table 1 ; see text. wide Building Society on the average size of new houses sold in Berkshire . Land prices in Berkshire have also been inflated by 45 per cent to take into account infrastructure costs . Table 2 shows these land prices . While the prices in South Paris are still generally higher, Berkshire prices increase extremely rapidly in the mid 1980s and were over 100 per cent higher by 1988 . Despite the difficulties in data availability and the definitional differences between the UK and France, the fact that a comparatively large proportion of the market for new housing comprises single family dwellings for sale makes comparison to some extent meaningful . The problem with Sweden is that this type of housing-especially in the case-study area-represents a fairly small share of the market . In the E4 Corridor, single family dwellings for sale accounted for only 15 per cent of completions during the 1980s, a further 16 per cent were self-promoted for owner-occupation. Most of the output comprised flats built for commune housing companies or for co-operatives, although this depended on the commune (Barlow and Duncan, 1992) . Commune landbanking appears to play an important part in housing land supply in the E4 Corridor. Most communes have large reserves, built up during the 1960s and 1970s (almost all undeveloped land in Taby is owned by the commune) . The length of time over which landbanks were built up and the fact that there are few transactions in any given year, makes it impossible to derive an `average price' of commune-purchased land . In 1990, interviews with planners suggested that the price paid by communes for `raw' land (i .e . greenfield sites with no infrastructure) was about SEK 50-60 per m2 (1988 exchange rate : £1 = SEK 10 .90; 1989 rate = 10 .56) . Communes sell land from their reserves at much higher prices, although these are limited by the maximum allowable under the SHL system . Land for flats, with infrastructure, is sold at prices which, in 1990, ranged from SEK 500 to SEK 850 per m 2 of built space . The norm at this time appeared to be around SEK 600-700, around the SHL limit . By 1992, prices had fallen to SEK 300-600 per m2. Prices for single family dwellings are higher, at around SEK 500-600 per m2 in 1992. Land prices for single family dwellings built outside the SHL system are much higher, though . At the peak of the house price boom in 1989, plots in desirable areas exceeded SEK 600 000-well above the maximum limit permitted under the SHL system (SEK 500 000) . By 1992, prices had fallen back to SEK 400 000-500 000 though . There are therefore clearly large absolute differences in the price of housing land in each case-study area. To what extent have the growth regions experienced land price Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at RICE UNIV on May 21, 2015 1 140 JAMES BARLOW E4 Corridor ...... ... ... ..... Berkshire . . . . . ... ... .... ... Toulouse South Paris Figure 2. Deflated land price index for single family dwellings (1984 = 100) . (Sources : see text) . inflation, though? Figure 2 shows the real change in housing land prices during the 1980s, with 1981 as a base year . While prices have risen in all areas, Berkshire stands out with a threefold rise since the lowest point of its cycle . In contrast, prices in the E4 Corridor were comparatively stable until the three-year boom in 1987-89 . Toulouse and South Paris experienced slightly rising prices . It is more useful, perhaps, to compare prices in the case-study areas with their national and regional averages, since this allows us to see the extent to which the land markets in the growth areas are `overheating' (Table 3). Not surprisingly, all the case-study areas are areas of relatively high land prices . Berkshire, for example, was over four times as expensive as the national average in 1988 and was almost always at least twice the national average. The E4 Corridor was also at least twice the national average throughout the decade . Toulouse and South Paris are also relatively expensive ; in fact, the latter consistently displays the highest relative land prices for all the case studies . Generally, the E4 Corridor and Berkshire were becoming more expensive during the mid to late 1980s, while there was no clear trend in Toulouse . South Paris appears to have seen a rise in relative land prices during this period, but the lack of a full time series hampers full analysis of the trend . Of course, it is possible that the growth areas are simply experiencing rates of land price inflation which affect the surrounding region as a whole. It is useful, therefore, to compare land prices in the case-study areas with those in the surrounding regions . This provides a good indication of any `local' effects causing the growth areas to overheat faster than neighbouring areas . Unfortunately we cannot perform this exercise in the French examples, but from Table 3 it can be seen that prices in Berkshire generally remained relatively constant in relation to the Outer Metropolitan Area during the 1980s . The same was true for the E4 Corridor. This therefore suggests that there were no specifically `local' factors causing rapid land price inflation . The key points to emerge from this analysis of price trends in the growth areas are the following. First, absolute price differentials are high, with Berkshire and South Paris standing at one extreme, and Toulouse and the E4 Corridor at the other extreme. Secondly, inflation pressures appear to be highest in Berkshire . Thirdly, Berkshire and the E4 Corridor do not display any specific Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at RICE UNIV on May 21, 2015 1141 CONTROLLING THE HOUSING LAND MARKET Table 3. Land prices in the case-study area compared to national and regional averages Year 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 E4/Sweden E4/Stockholm 358 302 249 253 227 209 249 283 337 Berkshire/ England and Wales Berkshire/ OMA 259 213 228 253 265 250 323 412 - 104 89 100 88 91 85 105 100 - 104 109 117 113 125 113 108 131 116 108 Toulouse/ South Paris/ France France 136 136 166 151 145 144 138 332 328 319 328 345 391 380 Note : Berkshire figures based on median land prices ; other case studies based on mean . Source: derived from data in Table I and national data . `local' trends. (We cannot determine whether this is the case in the French case-study areas.) It is now necessary to examine some of the possible explanations of these differences . We have argued that in order to understand the relationship between the planning system, land supply and land prices it is necessary to consider the extent to which supply is flexible (and over what period) and the different strategies adopted by developers and landowners . It is also possible that high house prices have driven up land prices, because developers operate a `residual' method of bargaining in the land market . The next section examines some of the possible reasons for the differences between the case-study areas . Land Supply, Developer Strategies and House Prices Table 4 shows the annual rates of land and house price inflation for Berkshire, together with the change in the amount of housing land sold and the number of dwellings completed . A striking feature of the table is the violent up and downswings in the amount of land traded and, to a lesser extent, the number of completions . The period 1982-83 was marked by a massive increase in sales of land, with a large rise in completions following in 1983-84 . By 1984-85, however, land sales were falling, with a decline in completions following in 1985-86 . There was another surge in land sales in 1985-86, but this time completions only increased slightly (in 1986-87) . In the period after 1986-87, land sales and completions fell dramatically as the recession in the housing market began to bite. These figures therefore suggest that in Berkshire speculative activity in the land market preceded completions by about 1-2 years during the 1980s . How do these trends compare with changes in house prices, though? From Table 4 it can be seen that the period 1982-83 saw an increasing rate of house price inflation, matching the large increase in land sales and completions . The slight fall in house price inflation in 1984-85 corresponds with a slump in land sales and, later, a fall in completions. By 1986-87 land price inflation was high (and growing), with land sales initially surging, then slumping . During this period, house price inflation was fluctuating considerably, while completions were generally falling . Finally, 1987-88 saw house price and land price inflation peaking, but land sales collapsing. Completions began to fall after a lag of 1-2 years . Thus, changes in house price inflation in Berkshire appear to match changes in land prices during the early 1980s (although the magnitude of changes is different for each) . After 1984-85, though, the sustained in- Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at RICE UNIV on May 21, 2015 1 142 JAMES BARLOW Table 4. Percentage changes in land and house prices, land supply, dwelling completions in Berkshire Year ending Land price House price 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 2.9 31 .5 14.4 25 .2 26.3 29 .4 76.7 3 .6 14 .5 4 .4 6 .1 18 .4 8 .2 20 .0 - Land sales 187 .0 57 .6 0.0 -56.7 188 .9 -20.8 -25 .2 - Completions -29 .0 25 .0 40 .0 1 .8 -19 .0 5 .5 -63 -24 .5 land prices (DoE `wide' series) ; house prices (derived from Nationwide Building Society and DoE special tabulations) ; land sales (DoE `wide' series) ; completions (DoE). Sources : crease in land price inflation-from 14 .4 per cent to 76 .7 per cent per annum-was only partly matched by house price inflation . This implies that land price inflation was either fuelled by speculative activity in the land market or an increasingly restrictive planning system . We can gain some impression of the level of speculative land trading in Berkshire from the timing of surges in land sales in relation to changes in land and house prices . As noted above, extremely large increases in land sales occurred during 1981-83, preceding increases in the rate of land and house price inflation . This suggests that developers and landowners were engaged in speculative activity during a period of relative calm in the housing market . These purchases of development land appear to have been translated into completions after a year or so, but the fall in house price inflation seems to have introduced excessive caution amongst developers as land purchases slumped in the mid 1980s . Land prices continued rising rapidly, however, inducing another surge in trading . While house price inflation was relatively high, land sales were declining, suggesting either a flooding of the market or tightening in the planning system . Further evidence for speculative activity comes from the balance between land sold with planning permission for housing and land sold without permission . Taking the difference between the DoE's `wide' and `narrow' land sales figures as an indication of the amount of speculative land sold (i .e. without planning permission), it is clear that in Berkshire there was a steady rise in sales of this type of land during the 1980s . The amount of speculative land sold as proportion of sales of non-speculative land grew from 28 per cent in 1981 to 93 per cent in 1984 ; fell to about 50 per cent during 198587 ; and then rocketed to 108 per cent in 1988 . The earlier period of rising speculative land purchase appears to tally with the activity in the land market prior to the 1983 rise in house prices and completions, described above. The relative decline in speculative land purchase seems to correspond with the downturn in the land and housing market from 1984-85 . These trends lend weight to the suggestion that there was a considerable amount of land trading prior to inflation in house prices . However, land sales data merely indicate the level of transactions in any given year . It is possible that future land availability was becoming more restrictive during this period (see Barlow, 1990, for details) . The fact that throughout the early to mid 1980s there was a `slippage' between planned completions (i .e . targeted under the county structure plan) and actual completions (i.e . including those granted on appeal and on windfall sites) would suggest that the planning system was quite flexible at this time . However, there was a reduction in the success rate of resi- Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at RICE UNIV on May 21, 2015 1143 CONTROLLING THE HOUSING LAND MARKET Table 5. Percentage changes in land and house prices, land supply and dwelling completions in Toulouse Year ending Land price 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 14.3 30.2 -6.4 -7 .7 48 .1 15 .6 -12 .2 59 .1 n.a . House price 20 .5 12 .7 -1 .7 2 .2 0 .6 14 .1 6.8 4.1 3 .2 Land sales Completions -22.0 -28 .2 18 .6 3 .1 -8 .3 2.8 43 .8 23 .1 n.a . -20.0 27 .6 38 .8 -24 .1 -1 .4 44 .7 62 .4 -33 .5 n .a . land prices (derived from AUAT data) ; house prices (derived from DDE data) ; land sales (AUAT) ; completions (DDE). Sources : dential applications and the proportion granted on appeal generally rose . In addition, `current housebuilding commitments'-the developers' planned output on allocated sites at a given time-fell substantially between 1976 and 1988 . In other words, developers were `building out' their sites-finishing them off without replacing their local landbanks-even during the height of the housing boom in the mid 1980s . There was also a slight rise in average building site density, while the average site became smaller in terms of permitted units and area . There could, of course, be various reasons for these trends . Rising land prices may have forced developers to increase the number of dwellings per site (cf. Cheshire and Sheppard, 1989) . It is also possible that growing anti-developmental protest and lobbying (Barlow and Savage, 1986; Short et al ., 1986) had an impact on the local planning process which resulted in a growing unwillingness of local authorities to sanction greenfield large-scale land release . This may have fuelled underlying speculative activity . Certainly, larger housing developers interviewed at the time were scathing about the activities of `speculative entrepreneurs', arguing that they fuelled inflation, led to increased competition and caused 'legitimate' developers to spend more time and resources devoted to land acquisition . Whether or not land supply in Berkshire was tightened during the 1980s, the system is very much a lottery for developers . In contrast, the planning system in Toulouse affords much less uncertainty for the development industry . Here, there is a significant 'pro-growth coalition' comprising local employers, developers, landowners, eight local municipalities, universities and financial institutions (cf. Dreulle and Jalabert, 1987). The planning system is geared towards relatively easy land release . The administration running Toulouse commune has generally favoured private-sector development and relaxed its planning policy in the mid 1980s by modifying the local POS and allowing higher densities. On the other hand, some other communes-especially those in the inner suburbs with socialist administrations-have been more concerned with controlling private-sector development and promoting HLM or joint public-private housing schemes . In addition, the fragmented nature of local government has led to inner-commune conflict over development pro- posals and a lack of overall planning coordination . However, the generally relaxed attitude towards new development in the metropolitan area as a whole is clear from the success rate of residential development applications . Between 1980 and 1989 only 8 .4 per cent of the 27 267 applications were turned down . Table 5 shows the annual changes in land and house prices, the amount of land sold and dwelling completions . During 1982-83 Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at RICE UNIV on May 21, 2015 1 144 JAMES BARLOW there was a sharp fall in land sales, with completions falling and then rising . This occurred against a background of high rates of land price inflation . The following year, 1983-84, saw a surge in land sales and completions, but falling land prices . There followed a period (from 1985 to 1987) of relatively stable land sales and initially falling completions . However, a sudden upturn in housebuilding occurred in 1987 . Despite the sluggish land sales, inflation was high, which may have accounted for the slow reaction of landowners to the rise in completions-although completions grew by 45 per cent in 1986-87 and a further 62 per cent in 1987-88, land sales did not take off until 1987-88 and continued at a high level until after the peak in housebuilding . House price inflation was relatively low throughout this period, broadly matching the change in land prices (albeit at a lower rate) up to 1985. After 1985, however, the surges in land prices were not matched by rapidly increasing house prices (e .g . 1986-87 and 1989-90) . Tou=louse The slow reactions of landowners in to inflationary booms and downturns, such as those in 1982-83 and 1988, suggest that they may be less well-organised-perhaps because of a fragmented ownership pattern-than their counterparts in Berkshire . Interviews with housebuilders confirmed that they tend to buy land only for their immediate use and pay the landowner once the scheme is completed. This implies that it is the developers, rather than landowners, who tend to have the upper hand in the Toulouse land market. It is also possible that the relatively flexible planning system, and the loosening of the POS, may have resulted in a flooding of the land market in 1987-89, leading to an initial surge in completions and a fall in land prices in 1988 . Cheap land has also been provided by the communes, departement and SEMs (mixed public-private development companies) through their use of pre-emption powers and the creation of special development zones . During the first half of the decade these were mainly to aid HLMs, but more recently they have been used to speed up private-sector development . An average of 16 ha per annum was bought using these powers during the 1980s, although by 1989 the amount was negligible . We should not, however, exaggerate the effect of pre-emption powers . Most communes have neither the administrative nor the financial resources to pursue a systematic policy of pre-emptive land purchase . Indeed, rapid land price inflation may deter communes from undertaking pre-emptive purchase because of the financial implications . A more important limitation on house and land price inflation is the general effect of the housing finance system . Since most of the housing built in Toulouse is under the PAP/ PLA/PC system, with limits placed on house prices and construction costs, house price inflation is dampened . This implies that developers in Toulouse have relatively little control over land costs and housing sales prices, and attempt to maximise turnover rather deal speculatively in land . The limited information on land sales and price inflation in South Paris means that we can say very little about the relationships in this area . However, the picture appears to be less straightforward than Toulouse or Berkshire, varying between each sub-market . In Essonne, it appears that parallel to a shift in commune policies in favour of new development after 1985, an anti-growth residents' movement began to emerge . Some local mayors were said to have blocked new development applications in the run-up to local elections . Since 1987 land reserves in the zones designated for future development have fallen from 928 ha to 793 ha, around five years' output at current rates of housebuilding . However, there has been intense pressure from farmers for revisions to the POS to allow more development and there has been a rise in the amount of land in the `speculative' market-i .e . land sales which were not for immediate development . Generally, communes were pursuing at relatively pro-development stance in the late 1980s. Vilmin (1987) found that 17 communes had a `negative attitude' towards development, 8 Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at RICE UNIV on May 21, 2015 1145 CONTROLLING THE HOUSING LAND MARKET Table 6 . Annual rates of price inflation, South Paris Apartment Houses Year ending St. Quentin MSP Evry 1987 1988 1989 1990 10 .2 -12 .6 54 .5 -2.3 45 .3 7.9 15 .8 20.7 17 .0 -6.3 13 .0 13 .7 Source : St. Quentin 12 .2 21 .0 3.2 9.8 MSP Evry -7.9 32 .6 7.3 0.1 16.2 11 .0 25 .7 -1 .8 derived from DRE data. were neutral and 42 were `positive' . The `negative' communes generally took this position because of their lack of a suitable tax base from which to provide the necessary infrastructure and/or their demography (a young population and no perceived need to increase the number of households) . Nevertheless, there has been a rise in anti-growth residents' groups in certain areas, although these have not yet reached the same level of organisation as those in South East England. This is especially the case in the west around Versailles and Hants de Seine, where residents' protest groups are said to be more strongly organised . However, in the core of the South Paris growth zone, Massy-SaclayPalaiseau, there is said to be effectively no anti-development pressure because the area is seen as `dead' and new development will bring in employment, housing and leisure facilities . Why is house price inflation limited in Toulouse but more acute in South Paris, despite the same planning model? Perhaps the most important reason is the fact that a growing share of development has been in the unregulated sector. Massy-Saclay-Palaiseau provides a sharp contrast to the new towns of Evry and St . Quentin. Here there is no unified land assembly by the local communes and a much lower proportion of dwellings are completed under the PAP/PLA/PC system. Prices tend to be much higher and inflation rates are more erratic (see Table 6) . There is not enough data available to examine the relationship between land and house price inflation in as much detail as Toulouse, but it appears that the price of new housing has risen steadily, and at an increasing rate, throughout the 1980s. We cannot, however, determine whether this follows or leads to the rise in land prices described above. The considerable local powers of Swedish communes mean there are noticeable differences in policies towards housing development within the E4 Corridor . In an area exposed to both market pressures and centralisation of planning (via the Housing Delegation), commune-level political choices remain crucial to the form and balance of housing promotion . These. are reflected in differences between communes in the share of housebuilding by promotion and tenure form, and landbanking (Duncan and Barlow, 1991) . Sundbyberg, for instance, is overwhelmingly dominated by municipal housing companies, which accounted for 96 per cent of total completions from 1980-89 . In complete contrast, only 7 per cent of completions in Vallentuna were in this sector, while 66 per cent were by co-operatives . There is evidence that there are also differences between communes in terms of their intervention in the land market . This arises partly from political differences because of growing problems in sustaining the traditional approach to land banking in the face of higher land prices and declining land availability . This has meant that some communes have found it increasingly hard to replace their land banks . For instance, Vallentuna stopped buying land in 1985 when it felt prices were too high ; Sollentuna aims to maintain a land bank sufficient for 60 per cent of production for the next 10 years, but is finding this increasingly expensive . There is some evidence that one responseused by Sollentuna and to some extent other Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at RICE UNIV on May 21, 2015 1 146 JAMES BARLOW Table 7 . Percentage changes in land and house prices, land supply, dwelling completions in E4 . Corridor Year ending 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 (-) Land price 11 .7 -4.9 27 .9 -9.8 12.7 0.0 5 .1 28.5 (28 .9) (22 .4) (18 .5) House price 13 .8 19 .1 3 .3 10 .5 2 .6 12 .7 -2 .7 13 .6 Land sales -41 .9 230.9 40.3 20.6 -3 .1 -4 .1 -25 .9 21 .4 (-4 .7) (53 .4) (-48 .8) Completions -12 .7 -17 .9 -19 .8 106 .0 -19 .0 -17 .3 -52 .0 25 .2 12 .4 53 .4 -24 .5 Estimated . Sources: land prices (SCB Data) ; house prices (measured as `production costs' ; SCB data) ; land sales (estimated number of transactions and average transactions size ; SCB data); completions (SCB data) . Conservative-controlled communes-is to sell land from their land banks at a high price for commercial development in return for planning gain in the form of low-cost housing units . As well as this more overt form of planning gain, private developers have begun to operate in a `semi-speculative' way (Barlow and King, 1992 ; Duncan and Barlow, 1991) by `suggesting' new schemes on private land to communes, with development involving a mix of office space and public and private housing . It is also the case that the planning and housing supply process in the E4 Corridor is not immune from political lobbying against new development . This appears to have increased since legislation in 1987 which gave more scope for residents to become actively involved in the planning process . Nevertheless, the tradition of corporatist negotiation between and within local state bodies and regional institutions of central government, together with the strong local political framework, plays a crucial role in containing this protest . What is the relationship between land supply and house and land price inflation in the E4 Corridor? The dampening effect of the SHL system, which places limits on the land price element in housebuilding costs, and the fact that the bulk of new housing is built on land obtained from commune land banks should mean that there is only a limited effect of land supply constraints on the price of new housing . However, it is clear that there is at least some inflation in the housing land market and prices have crept up to the SHL limits . Table 7 shows the key land market indicators for the single family dwelling sector, and is thus only a partial picture . We have not been able to obtain equivalent data on land supply and prices for apartments . There are a number of striking features to the figures in this table . First, until 1987 land price inflation was stable, with rises in one year being matched by falls in the next, despite sharp swings in the volume of land sold . Secondly, the period after 1987 saw much more extreme rates of land inflation, but no overall change in land sales . Thirdly, the change in house prices has generally followed land prices, although at a lower rate . Unfortunately, we have been unable to obtain house price data for the period after 1988 . However, the fact that the high rates of land price inflation in 1987 and 1988 did not result in a sustained pattern of house price inflation suggests that the SHL system has been able to hold down house prices . This in turn suggests that housing developers will have faced reduced profit margins during this Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at RICE UNIV on May 21, 2015 CONTROLLING THE HOUSING LAND MARKET period, since they were experiencing rising land (and construction) costs but stable house sales prices (see Barlow and King, 1992) . The primary factor behind land price inflation in the E4 Corridor appears to be the general level of demand for land for commercial development in the Stockholm areas as a whole. This has pushed up prices in the open market, ultimately the source of all development land, and it remains to be seen how long the subsidy system can be maintained in the face of such levels of inflation . Conclusions This paper has examined the relationship between planning systems, land supply and house and land prices in growth areas in Britain, France and Sweden . We have seen how the very different approaches to housing provision and planning result in different land market outcomes, despite similar levels of growth in local housing and labour markets. The housing land market in Berkshire was subject to considerable speculative activity during the 1980s. Landowners and developers displayed high degrees of risktaking behaviour-even if their expectations were not always fulfilled . As we saw, house price inflation was to some extent dislocated from land price inflation by the end of the decade. This suggests that the influence of the local planning system over land market activity is less direct than is commonly assumed, and the volume of transactions is to some extent independent of land release by local planning authorities . However, it is also likely that speculative activity is exacerbated by the uncertainty of the planning process and the perceived tightening of land availability in the 1980s . The British case study therefore suggests that while the British planning system may provide a degree of short-run flexibility-i .e . a capability of responding to immediate changes in demand, assuming sufficient land has been identified as available-the uncertainty over the longer run provokes speculative behaviour on the part of developers and landowners . 1147 The French examples provide an interesting contrast . These show that a zoning system can be more flexible in that it responds comparatively quickly to increased demand in the short run . However, much depends on local conditions . Political differences between communes means variable outcomes in zoning terms, as well as differences in emphasis towards the alternative types of housing finance . In Toulouse, the generally pro-development stance has resulted in large-scale zoning in an area of fragmented landownership pattern and disorganised landowners . This has led to periodic gluts and famines of land release, which have led to swings in land price inflation . However, the emphasis on price-regulated housing (through the PAP, PLA and PC systems) has held down house price inflation . The implication of this description is that there is a continually shifting balance of power between landowners and developers, with the former weak during gluts and the latter facing reduced margins during famines as land prices rise and house prices remain relatively stable. The South Paris example lends weight to the idea that house price inflation is limited by the finance system . As we saw, far less new housing was price controlled than in Toulouse and price inflation rates were much higher. This was also the case within the South Paris area, with the new towndominated by price-controlled housingexperiencing low inflation . However, extremely high base level house prices in the Paris region as a whole appear to have resulted in high absolute land prices throughout the 1980s . These may have been exacerbated by growing constraints on land availability and by speculative trading . Finally, the approach in the E4 Corridor is wholly different . Here, long-term land banking by communes acts as a buffer against price inflation in the `open' land market . The finance systems acts as an additional brake against land price inflation . Nevertheless, the E4 Corridor is not immune from inflationary pressure. Communes have found it increasingly expensive to replenish their land banks . Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at RICE UNIV on May 21, 2015 1 14 8 JAMES BARLOW Furthermore, upward pressure on open market land prices has led to rising subsidies during the 1980s . Ultimately, inflation in land and construction costs is therefore translated into inflation in the SHL system. The analysis of the growth regions therefore reinforces the points made in the introduction to the paper . First, the responsiveness of land supply to changes in demand can only be assessed in relation to the period over which the analysis is being conducted . There is no absolute long or short run, since these depend on the land market and political conditions, as well as the prevailing planning model. Secondly, the land market strategies adopted by landowners and developers vary considerably and are partly shaped by the prevailing planning model . Most important is the way in which speculative and risk-taking behaviour is dampened by increased planning certainty . Thirdly, local differences within countries, and even within regions, arise from the independence of local authorities in planning terms . There is no absolute control or fixity of land supply within planning systems, either spatially or over time . Thus, we cannot understand the relationship between land supply, planning and land and house price inflation in isolation . The prevailing structure of housing provision and planning will shape the precise outcomes in that area. However, this does not mean that we cannot draw any generalised conclusions . There is clearly a link between risk-taking behaviour and the level of certainty in planning systems . The Planning and Compensation Act (1991), which gives more weight to local plans, may ultimately shift the British approach towards a variant of the French model . Acknowledgements This paper was based on research carried out in three ESRC-funded projects : D00232280 (housing provision in European growth regions), R000231648 (housing and labour market relations in a British growth region), and R000232698 (the politics of urban development in European growth regions) . Funding was also provided by the Swedish Council for Building Research (BFR) . I would like to thank my co-researchers on these projects, Simon Duncan and Peter Ambrose, for their help and comments, and Kate Williams for data analysis . Christine Corbilld at the Institute d' Amenagement de la Region de 1'Ille de France (IAURIF), Serge Olivier at the Direction D6partemental de l' Equipement de l' Essonne and M . de Cornuellier at SAFER (Paris) all provided their time and help with data, as did members of the CIEU (Universite Toulouse-Le Mirail) and the AUAT (Toulouse) . Finally, I would like to thank the Department of the Environment and Nationwide Building Society for providing much useful data on Berkshire . Note 1. These issues are currently being investigated in the same case-study areas . References BALL, M . (1983) Housing Policy and Economic Power: The Political Economy of Owner Occupation . London : Methuen . BALL, M., HARLOE, M . and MARTENS, M. (1988) Housing and Social Change in Europe and the USA . London : Routledge. Who plans Berkshire? The housing market, house price inflation and the developers, Working Paper No . 72, Centre for BARLOW, J . (1990) Urban and Regional Research, University of Sussex . BARLOW, J. (1992) Self-promoted housing and capitalist producers : the case of France, Housing Studies, 7 (forthcoming) . BARLOW, J . and DUNCAN, S . (1992) Markets, states and housing provision : examples from European growth regions, Progress in Planning (forthcoming) . BARLOW, J . and KING, A . (1992) The state, the market and competitive strategy: the housebuilding industry in the UK, France and Sweden, Environmental and Planning A, 24, pp . 381-400 . BARLOW, J . and SAVAGE, M . (1986) The politics of growth: cleavage and conflict in a Tory heartland, Capital and Class, 30, pp . 156-182. CHESHIRE, P . and SHEPPARD, S . (1999) British planning policy and access to housing : some empirical estimates, Urban Studies, 26, pp. 469-485 . CONRAN ROCHE (1989) Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at RICE UNIV on May 21, 2015 Costs of Residential De- CONTROLLING THE HOUSING LAND MARKET velopment: Final Report prepared for the Department of the Environment. London : Conran Roche . 1149 in: M. BREHENY and P . CONGDON (Eds) Growth and Change in a Core Region : The Case of South East England, pp . 150-181 . London : S . and JALABERT, G . (1987) La technopole toulousaine : le developpement de la vallee de l'Hers, L'Espace Geographique, 1, pp . 15-29. DUNCAN, S . (1989) Development gains and housing provision in Britain and Sweden, Pion . LSL (1989) Fler Bostader, Farre Kontor. Stockholm : Lanstyrelsen i Stockholms Lan . MONK, S ., PEARCE, B . and WHITEHEAD, C . (1991) Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 14, pp . 157-172 . Research Unit, Department of Land Economy, University of Cambridge . MYNORS, C . (1991) The Planning and Compensation Act (3) : development plans, minerals and waste disposal, The Planner, 13 September, pp. 7-8 . SHORT, J ., WITT, S . and FLEMING, S. (1986) House- DREULLE, S . and BARLOW, J . (1991) Marketisation or regulation in housing provision? Stockholm and the E4 Corridor in the European context, DUNCAN, Scandinavian Housing and Planning Research, 8, pp. 197-219. and MONTIN, S . (1991) Decentralisation and control : central and local government relations in Sweden, Policy and Politics, 18(3), pp . 165-180 . HOOPER, A ., PINCH, P . and ROGERS, S . (1989) Housing and land availability in the South-East, ELANDER, I . Planning, land supply and house prices : a literature review. Monograph 21, Property building, Planning and Community Action . London : RKP. (1987) Etude du fonctionnenment du marche foncier de 1'Essonne . Direction D8partementale de 1'Equipement de l'Essonne, Services des Etudes et de la Prospective . VILMIN, T . Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at RICE UNIV on May 21, 2015