Why I Can't Spell: A Writer's Spelling Struggles

advertisement

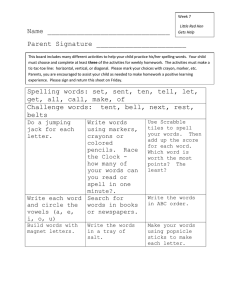

Why Stevie Can't Spell After more than three decades of mangling words, a mortified writer sets out to get some answers By Steve Hendrix Sunday, February 20, 2005; Page W26 On a chilly December morning, I joined the ranks of little kids filing into Rolling Terrace Elementary School in Takoma Park. They waddled under oversize backpacks and tugged Dora the Explorer rollaboard book bags through the double doors. I carried a black briefcase. We were all a few minutes late, and we all stopped like statues in the hallway for the reciting of the Pledge of Allegiance, first in English, then in Spanish. Then the kids melted into their classrooms, and I went into an office near the second-floor water fountains for my first spelling test since Donald Rumsfeld was the secretary of defense . . . under Gerald Ford. I didn't do very well. Melissa Salvesen, Rolling Terrace's reading specialist, quizzed me on a list of 27 words I chronically misspell. I had e-mailed the list to her myself. Even knowing what to expect, I botched 13 of them on a test featuring such grade-school softballs as elephant, piece, refrigerator, forest, towel, jewelry and trailer. The author poses with third-graders, from left, Amalia Perez, Isabel Hendrix-Jenkins and Dillon Sebastian. (D.A. Peterson) "Okay," she said, nodding her head slowly as she scanned the wreckage on my notebook paper. "You really can't spell." That I knew. What I wanted to find out was why. I AM THE WORLD'S WORST SPELLER. I have been all my life. My homework -- from Miss Pedrow's third-grade language arts class to Dr. Gurevitch's doctoral seminar in persuasion and attitude change -- all came back with the measles, solid red marks from top to bottom. "Good writing, atrocious spelling" was the verdict of just about every essay contest I ever entered (even those I won). I don't misspell just hard words (diaphanous, anyone? soliloquy?); I misspell words like "maybe" and "because" and "famous." I misspell my own mother's name, Elfreida. My misspelling is epic. It's rich and vibrant and ever changing. It can even be fun. "I think of them as little puzzles," my Post editor K.C. Summers once said of the find-the-funny-word challenge inherent in proofing my raw efforts. But mostly it's just hugely embarrassing to be a professional writer who is routinely laughed out of Scrabble games. Not to mention perilous. I was put on probation at an Atlanta newspaper for causing excessive spelling trauma on deadline (a kindly copy editor began covering for me). And I've watched every editor I've ever worked for go through a sort of five-step process of realization (disbelief, anger, anger, resignation, anger) before finally assigning some beleaguered proofreader to shadow my every keystroke. At this paper, when one of my howlers (partician when I meant partition) made it into print and drew a rebuke from the ombudsman, I reminded K.C. -- ha-ha! -- of her "little puzzle" comment from happier days. "I really think of them more like little land mines," she said this time. Let's take one example: itinerary. Iteneriary is one of the dozens of words that bring me to a complete standstill. I can be typing along at a brisk pace when my brain feeds a word like itenirary down to my flying fingers, and they freeze over the keyboard like mummified buzzard claws. Itinerary. I-T . . . E? . . . I? Pretty sure it's I. N is easy. Another E? or is it A? . . . R . . . Two Rs? A? A-R-Y. Itinerrary. I once spell-checked a 2,000-word article I had written for the Post's Travel section and found I had spelled itinerary four ways, none of them correctly. It was a pitiful tally, made worse by the fact that it blinked at me in the middle of a newsroom filled with some of the best writers -- and spellers -- in the country. I could hear them all around me, blithely tapping out the 100,000-plus words that go into the paper every morning, most spelled correctly on the first go. People who write for big-city newspapers are supposed to be able to spell. The island of misfit toys, this is not. Being humiliated by spell-check is pretty much a daily occurrence for me, but something about seeing four errant itineraries spurred me to action. I sat and repeated the word over and over and over, out loud, the way you memorize a phone number: I-T-I-N-E-R-A-R-Y. I was going to screw that simple nine-letter pattern into my brain if I had to repeat it 10,000 times. Hey, I can do it with an ATM number. Surely I could do it with the language I use every day to make my living. The chance to test myself came up within a day or two, as I worked on a story about backpacking through Alaska's Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. "But as the weather soured again, the evening meal became more than an item on the . . ." And I nailed it. Itinerary. I believe it was the first time -- in either my 14-year professional life as a writer or my 39-year personal life as, um, a person -- that I ever spelled itinerary correctly without any kind of assist from a dictionary, computer, copy editor or wife. The next week, I got it wrong again. Itenerry. The other day, I spelled it itenirary. t's a shame, because I love words as much as they seem to hate me. I love learning them and using them and having fun with them. I'm an incurable punster -- wordplays pop into my head so constantly that I have to make an effort not to blurt them out like a Tourette's sufferer. My literary idols are such master wordsmiths as P.G. Wodehouse, William Faulkner, Patrick O'Brian and Richard Ford. I read tons. I have a robust vocabulary. I just can't spell. The author poses with third-graders, from left, Amalia Perez, Isabel Hendrix-Jenkins and Dillon Sebastian. (D.A. Peterson) I know many people assume it's because I'm too lazy to reach for the dictionary. One of my colleagues recently summarized her 'nuff-said attitude toward misspellers by quoting to me the entirety of Stuart Little's curt spelling lesson to a class of grade-schoolers: "A misspelled word is an abomination in the sight of everyone. I consider it a very fine thing to spell words correctly, and I strongly urge every one of you to buy a Webster's Collegiate Dictionary and consult it whenever you are in the slightest doubt. So much for spelling. What's next?" Ah, the pitiless doctrine of Just Look It Up. It's hard to explain to my colleague, much less to E.B. White, that I'm "in the slightest doubt" with about every 20th word I write. Or that I'm sometimes too far at sea to even find it in the dictionary. (I once spent 20 minutes rewriting "mosquito" because I couldn't even get close enough for spell-check to take over.) Or that in the instant between looking up from the dictionary and turning to the keyboard, I can entirely forget what I've just seen (leaving me, at worst, with one index finger on the page while I peck out a letter at a time with the other). A far more appealing diagnosis of my affliction, if you ask me, is a growing body of evidence showing that some chronically awful spellers have an actual neurological misfire, a kind of dyslexia that keeps the most well-intentioned brain from remembering what words "look" like when it comes time to write them. One thing I can spell, people, is d-i-s-a-b-i-l-it-y. If this pans out, I may be able to get a better parking place at the mall. But what most people tell me, particularly those who bemoan the national deterioration of spelling in this age of Toys R Us storefronts and "i luv u 2" e-mails, is that what failed me was liberalism. I am, they say, a collateral casualty of the Reading Wars that have raged through elementary classrooms since the 1970s. That's when disciples of "whole language" reading instruction -- young academics addled by Vietnam and fed up with authority, rules and standards -- sent the Friday spelling quiz the way of slate chalkboards and penmanship training. For decades, parents schooled under more rigorous methods have been puzzled -and often outraged -- to see their kids' work come home riddled with the uncorrected errors of "inventive" and "magic" spelling. "We've been shortchanging spelling for about the last 30 years," says Richard Gentry, a Florida author who champions better spelling instruction in school districts across the country. Most whole-language approaches ignore the individual phonemes that are the building blocks of words -- the /eye/, /tin/, /eh/, /rare/ and /ee/ that make up itinerary -- in favor of teaching the "whole word," all of a piece and only in the context of other lessons. "The notion with whole language was that spelling wasn't all that important," Gentry says, "that if kids became good readers and writers, they would 'catch' expert spelling. We now know that they don't." It's not that all of those progressive enthusiasms were wrong, says Gentry, who ran Western Carolina University's reading center for 16 years. He cites the growing emphasis on good children's literature, for example, as a vast improvement over Dick and Jane's anesthetizing plot lines. And encouraging kindergartners to write, even in their emergent scribble-scrabble way, was a great leap forward. "A lot of good practice came out of whole-language theory," Gentry says. "The piece they got wrong was spelling. And spelling is phonics." Could it really be that itinerary stymies me to this day because a tie-dyed American pedagogy assumed that correctly spelled words would simply accumulate like sandburs as I explored the richer pastures of reading for pleasure and creative writing? Maybe it's time to go back and learn my letters. I CHOSE ROLLING TERRACE FOR A MIDLIFE SPELLING INTERVENTION because it's where my two daughters attend school. It is, in fact, where my daughter Isabel won the second-grade spelling bee last year. It turns out they're teaching spelling again. When I asked Melissa Salvesen, the reading specialist, if Montgomery County's new "word study/spelling" curriculum, which seemed to be serving Isabel so well, had anything to offer her dad, she agreed to create a souped-up variation of the program. My first test, the one for which I posted a dismal 52 percent, was meant to set a benchmark. I would take another one after the lessons to see, basically, whether the lame shall ever walk. "You do have some trouble with basic patterns," Salvesen said after poking diagnostically through the ashes of my quiz. "You have a little trouble with double consonants. And you're not really sure how to use y as a vowel." I squirmed a little. Could we close the door? "But most of what you get wrong are irregular words. You know the letters that are supposed to be in the word, but you put them in the wrong order, or you replace a correct vowel with an incorrect vowel. You're trying to spell it the way it sounds, and you're basically just guessing." She gave me a sheaf of work sheets she had copied from one of the books the county uses in its new spelling program. My homework. The Miss Grundys among you will be glad to know there is a growing level of spelling accountability in Montgomery County schools. Starting in first grade, classrooms feature a list of high-frequency, grade-appropriate mots justes on the "word wall," which lengthens through the year, and students are expected to get these right when they write. Kindergartners still get a pass with their starter list (he, she, the, and), but in first grade the rules of engagement now allow teachers to unholster the red pen. The author poses with third-graders, from left, Amalia Perez, Isabel Hendrix-Jenkins and Dillon Sebastian. (D.A. Peterson) These days, however, word study is about more than word lists. For beginners, it's about breaking words into individual chunks of sound and the letter combinations that make them up -- lots of variations on sounding out the separate syllables while clapping out their rhythms and other basic phonetic training. In first grade, after most kids have broken the essential code of reading, word study becomes more about sowing the rules of English spelling into little minds -- "i before e, except after c," except when it's not, and other such fickle tenets -- without scaring the bejesus out of them. "Okay, kids, your job is to help me collect all the words in this book that end in the letters ed," says Mrs. Burn, clapping her hands in the universal teacher semaphore for "Quiet down, we're starting something new." The 20-odd third-graders gathered on the brightly colored rug at her feet tame their twitching enough for her to go on. "As I read Galimoto, I want you to pay attention to any word that ends in e-d. If you hear one, raise your hand, and we're going to make a list at the end of each page. Now, who can tell me what it means when a word ends in e-d? Amalia?" Elizabeth Burn is my daughter's dynamo of a third-grade teacher. She has agreed to let me audit a word-study lesson, so I squeeze into a pygmy chair and listen hard for the e-d words as she reads Karen Lynn Williams's story of a Malawian boy who collects wire to build a toy. (It happens to be a book I've read to my own kids dozens of times, which gives me, I think, an edge on the other pupils.) After we collect a list of 40 words, we sort them into three columns based on the sound of their endings: /t/ (looked, rushed), /d/ (dried, shrugged) and /ed/ (illustrated, guided). "It's not spelled with a t, is it?" asks Mrs. Burn, pointing at the word "pushed." I shake my head. "It just sounds like that." By the time she gets through some of the "soft rules" for e-d words (double the last letter on some, change y to i on others, etc.), I'm hearing basics laid out in a way I sure don't remember from Miss Pedrow's class. "Look how excited they are by spelling," Mrs. Burn says to me as my classmates break into groups to sort words. "It's like a treasure hunt to them. We used to give them these hard and fast rules, and the kids would find so many exceptions it would freak them out. Now we get them to see the general tendencies and patterns that hold true more often than not." As a guest in the class, I decide it wouldn't be appropriate to climb up on a desk and shout at the kids to run for their lives. But someone should warn them that the task they've been handed -- making sense of English spelling -- is one that would have had Hercules looking back wistfully on his Augean stable days. The "general tendencies and patterns" of English orthography are about as consistent as congressional ethics rules. Ours is a Gordian knot of a language, a tangled skein of threads pulled from dozens of alien dialects and balled into the richest, most expressive and downright maddening lingo on the planet. There's plenty of blame to go around -- curse you, Greeks, Saxons and Normans -- for the fact that oven doesn't rhyme with woven, laughter does rhyme with rafter and colonel is identical to kernel. "We call them wacky words," says Burn. "O-n-e is pronounced one? Explain that to a firstgrader." The combination o-u-g-h variously makes the sounds of tough, through, though, thought and plough. O-e serves goes, shoes, does and amoeba. This is like an arithmetic in which 5 plus 3 sometimes equals 8, and sometimes 11, 23 or 75, for no particular reason that you can learn other than memorizing hundreds of irregular equations. It doesn't need to be this way. Did you know they don't really have such a thing as misspelling in Italy, Spain, Portugal and other countries with a more straightforward orthography? Ask a fellow on the streets of Lima how to spell abogado, and he'll simply repeat the word more slowly. It's like asking someone in Washington to spell FBI. "Those are simpler, phonetically based systems," says Gentry. They enjoy something much closer to a one-to-one correspondence of a single letter or letter combination to a single sound. "In Italian, they have 33 letter combinations to spell 25 sounds. In English, we have about 1,120 letter combinations to make 44 sounds." It isn't confusing just for bad spellers when there are at least a dozen ways to spell the long e sound: peel, key, tea, phoebe, tangerine, protein, fiend, she, people, ski, debris and quay. The bizarro spelling makes English incredibly difficult to learn, particularly for adults studying it as a second language, and acts as a drag chute on efforts to boost literacy. Ever since a 13thcentury monk named Orm, no doubt tugging his halo of hair in frustration at the unholy mess he was forced to transcribe, became the first evangelist for spelling reform, men of letters have called for some serious tidying up of the English lexicon. They've included Mark Twain, Teddy Roosevelt, the editors of the Chicago Tribune and George Bernard Shaw, who famously pointed out that "ghoti" could logically be pronounced fish using familiar English letter combinations (the g-h from rough, o from women and t-i from motion). Until about 350 years ago, spelling didn't even count in English, according to Naomi Baron, an American University linguistics professor and author of From Alphabet to Email: How Written English Evolved and Where It's Heading. Before the mid-17th century, Baron says, there was no notion of standardized spelling among the few who were taking quill to paper. "The Shakespeares and Miltons of the world might have spelled fish three different ways in a single work," Baron says. Shakespeare couldn't spell? And you're giving me a hard time? We orthographically afflicted love to cite luminaries who were famously rotten spellers, Thomas Jefferson, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Herman Melville, Woodrow Wilson and John Irving among them. Some people, even geniuses, just can't spell. "I see it all the time," says Salvesen, the reading specialist. "Some kids can just look at the word preposterous and spell it. Others can see it a thousand times and never get it right." The author poses with third-graders, from left, Amalia Perez, Isabel Hendrix-Jenkins and Dillon Sebastian. (D.A. Peterson) And why, I ask as someone in the latter camp, is that? Richard Gentry thinks the research is now clear -- it's in the brain. Recent studies using functional MRI analysis have not only begun to map the areas of the brain we use in reading and writing, they've shown how a neurological glitch in about 20 percent of people may make them chronically poor spellers. In brief, according to Gentry's summary in his book The Science of Spelling, when a kindergartner is learning to read, two areas of the left side of her brain are principally engaged, one in the left inferior frontal gyrus and the other back in the left parieto-temporal system. These two areas are where the constituent sounds, or phonemes, of a word are recognized, the /k/, /a/ and /t/ sounds of cat, for example, and then where they are broken up and put together to make a complete word: /k/+ /a/+ /t/= cat. Both of these areas of the brain are relatively slow and analytical, methodically dissecting words into bits to understand what they mean. Think of how a 5-year-old sounds out words. But at some point, usually a year or two after the learning process begins, she crosses a cognitive threshold and shifts from being a beginning reader to a fluent reader, a skill that relies on a third area of the brain, the left occipito-temporal. Instead of analyzing parts to identify the word, this area instantly recognizes the entire word. Reading goes from a halting letter-by-letter toil to a lovely word-by-word glide. "It's like sailing on a nice breezy day," says Sally Shaywitz, the Yale neuroscientist who conducted most of the research cited by Gentry. "Reading becomes a pleasure." That third zone -- the "word form area" -- is your personal dictionary. Once you have read a word five or six times correctly, your brain has stored a model of it that includes all the word's important features: how to pronounce it, how to spell it and what it means. That is, unless you're one of about 20 percent of readers who have trouble bringing the areas in the back of the brain on line. For them, according to functional MRI scans, the left parietotemporal and occipito-temporal stay relatively quiet, with most of the reading activity remaining in the frontal area. They may build up compensatory pathways, but they're not reading the normal way. What researchers think they are seeing in those scans is dyslexia in action. And some of them think it's also the neurological core of bad spelling. "If you don't activate Area C, you'll never be a good speller," Gentry argues. "That's where you 'see' a complete word in your mind's eye, whether you're reading it or writing it. And if you can't visualize it, you're just winging it based on what it sounds like. In a language with as many irregularly spelled words as English, you're going to be wrong a lot of the time." Researchers have long known that spelling and reading are tightly linked. Shaywitz says spelling is probably the more difficult of the two processes. "Reading is transforming letters into sound," she says. "Spelling is just the reverse, but you don't start with something you can see on a page." The dyslexia Shaywitz sees in her lab may explain why some people can never learn to spell. "Poor spelling may well be the last remnant of dyslexia that a person has otherwise compensated for," she says. "But it's something we haven't looked at directly." And what would she hypothesize about a person -- a good-hearted, mid-career journalist, say -- who writes tens of thousands of words a year, reads millions more, and still can't pass a grade-school spelling quiz? "I'd like to study that person," she says. You're on. IT'S SNOWING IN NEW HAVEN when I slip on the headphones at the Yale Center for the Study of Learning and Attention. Soothing voices recite words and sounds into my ears, part of the battery of tests I face before I get my head examined. These modest rooms, in a low-rise building around the corner from the Yale Repertory Theater, are the epicenter of recent advances in the scientific understanding of reading and dyslexia. Shaywitz runs the National Institutes of Health-funded center with her husband, Bennett Shaywitz. A 2003 cover story in Time magazine about her work is framed on the wall of the lobby where hundreds of parents and students come each year -- drawn by her national reputation and her best-selling book Overcoming Dyslexia -- to solve the painful mystery of what went wrong with Johnny's reading. The center is a place filled with stuffed animals and feel-good posters, reflecting the age of the typical clientele. "Am I the first person you've ever tested who wasn't wearing Hello Kitty sneakers?" I ask examiner Jennifer Koch as she has me assemble patterned blocks. "Oh, no. We test a lot of Yale undergrads, as well," she says. That's who I meant, but I let it go because it's time for my appointment with the MRI. The author poses with third-graders, from left, Amalia Perez, Isabel Hendrix-Jenkins and Dillon Sebastian. (D.A. Peterson) The four-block walk to Yale-New Haven Medical Center is a strangely stirring one. Am I about to learn that something is amiss with my brain? I have some of the symptoms of dyslexia: horrible spelling, serious difficulty remembering names and numbers, a failure to learn the rudiments of a foreign language in spite of two years of college French and a summer in Normandy. But I'm missing the big one -- profound reading trouble. Although I'm a slow reader, I'm a voracious one. I read for pleasure every night of my life. We don't have cable. "You're not a classic dyslexic, no," Bennett Shaywitz says in his office two floors above the basement MRI room. "But it's very possible that you had reading problems you've been able to compensate for very well." They finally roll me into the dark opening of the MRI machine. For 40 minutes, magnets grind around my head, taking pictures of my innermost thoughts. (I focus on pure ones -- it wouldn't do to have a compromising picture of Liv Tyler pop up on the monitor.) The actual test amounts to clicking a button in response to a variety of word games and patterns projected on a screen at my feet that are designed to stimulate the suspect areas of my brain to see them at work. When Sally Shaywitz calls after a few days, she has good news and bad. "Well, you're really smart," says this eminent authority on brains. "On our vocabulary tests, you scored about as high as you can possibly score. Also on the reasoning part, you're way, way in the superior range." I wonder if she could put that in letter form, addressed to: All Editors, The Washington Post. And on spelling and reading? "Let's call it average," she says. Specifically, I land in the frankly so-so 44th percentile on the part of the Nelson-Denny comprehension exam given under strictly timed conditions. But on the part with relaxed timing, my level doubles to a gentlemanly 85th percentile. "You have all the elements of reading," Shaywitz says. "But they're not firmly ingrained. When you're forced to do it quickly, you lose something." The MRI confirms it. The Shaywitzes see the lights go on in the usual reading areas of the left hemisphere. But they also find an unusual level of action on the right side of my brain, in the areas where dyslexics tend to build new pathways to make up for misfires in the normal ones. "It all fits together, our clinical exams and our neurobiological exams," Shaywitz says. "You had the underlying threads of dyslexia, but you've compensated for it really, really well. When you have time, you do well. But when you have to do things very quickly, it's not automatic. Your autopilot, for spelling and for reading, just isn't there." As a youngster, Shaywitz says, I was probably getting just enough information and pleasure from reading to push through some amount of dyslexic drag. And the more I read, the more compensatory tricks my brain wired into itself until I became fluent, at least under relaxed conditions. It's only when the heat is on that my reading goes a little wobbly and, even more often, my spelling collapses in a heap. It's probably one of the lesser beaten tracks to a career of deadline writing. On the train home from New Haven, I work on my Rolling Terrace spelling assignments. Sitting across the table from a man reading the Financial Times, I beaver away on work sheets decorated with cartoon dogs and elephants. Our eyes meet, and I realize I've been practicing the short e sound out loud. A few days later I'm ready for Melissa Salvesen's final quiz. I flunked my first one, bungling 13 out of 27. This time I miss 14. Including itinerary. Poor Mrs. Salvesen. There will be no "By-George-I-think-he's-got-it!" moment between her Henry Higgins and my Eliza Doolittle. In spite of her best efforts, I still drop my h's (although I tend to add an unnecessary one to crystal). "You finished all the work sheets?" she asks skeptically. "If you had regular direct instruction, I'm sure you would improve." I'm sure I wouldn't. If my brain hasn't figured out a way to spell itinerary by now, it probably never will. Science has spoken. And so I look ahead to many, many more productive years of dismembering English words. Let's see, call it 25 stories for each of the next 30 years, about 1,500 to 3,000 words apiece, plus thank-you notes, e-mails and grocery lists, merrily misspelling at a rate of seven to 10 words per . . . Well, it all adds up to quite a lot of "magic" spelling. I can't tell you exactly how much, though. I'm one of those people who just can't do math. Steve Hendrix is a staff writer for the Post's Travel section. He will be fielding questions and comments about this article Tuesday at 1 p.m. at washingtonpost.com/liveonline.