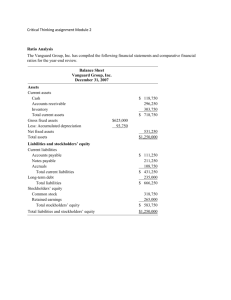

Foundation of financial management

advertisement