murphy2013

advertisement

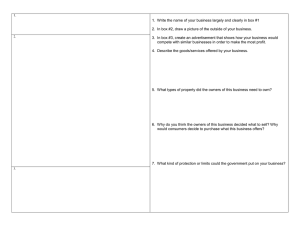

SMALL ANIMALS Assessment of owner willingness to treat or manage diseases of dogs and cats as a guide to shelter animal adoptability Molly D. Murphy, DVM, PhD; Janice Larson, PhD; Allison Tyler; Vanessa Kvam, BA; Kristen Frank, BA; Cheryl Eia, DVM, JD, MPH; Danelle Bickett-Weddle, DVM, PhD, MPH; Kevan Flaming, DVM, PhD; Claudia J. Baldwin, DVM; Christine A. Petersen, DVM, PhD Objective—To determine community approaches to medical and behavioral diseases in dogs and cats. Design—Cross-sectional descriptive study. Sample—97 companion animal veterinarians and 424 animal owners. Procedures—Companion animal veterinarians in central Iowa ranked medical or behavioral diseases or conditions by what they thought most clients would consider healthy, treatable, manageable, or unhealthy (unmanageable or untreatable). In a parallel survey, cat- or dogowning households in central Iowa responded to a telephone survey regarding the relationship of their animal in the household, owner willingness to provide medical or behavioral interventions, and extent of financial commitment to resolving diseases. Results—One hundred twenty common health or behavioral disorders in cats and dogs were ranked by veterinarians as healthy, treatable, manageable, or unhealthy (unmanageable or untreatable) on the basis of their opinion of what most clients would do. Findings were in congruence with animal owners’ expressed willingness to provide the type of care required to maintain animals with many acute or chronic medical and behavioral conditions. In general, owners indicated a willingness to use various treatment modalities and spend money on veterinary services when considering current or previously owned animals as well as hypothetical situations with an animal. Past experiences with veterinary care in which an animal did not recover fully did not diminish the willingness of respondents to use veterinary services again in the future. Conclusions and Clinical Relevance—These results provide a baseline indication of community willingness to address medical or behavioral conditions in dogs and cats. These considerations can be used in conjunction with Asilomar Accords recommendations to assess adoptability of cats and dogs in animal shelters. (J Am Vet Med Assoc 2013;242:46–53) T rying to find all relinquished and stray companion animals a home is a challenge for animal shelters. Although many animals brought to shelters are healthy and sociable, a certain number of animals may arrive at shelters with major health or behavioral issues, which may hinder their adoption. The purpose of the study reported here was to determine what types of behavioral or medical issues owners would be willing to address and treat and how companion animal veterinarians would classify various diseases or behavioral issues according to what they thought most clients would consider to be healthy, treatable, manageable, and unhealthy (unmanageable or untreatable). These health status categories were developed in August 2004 at the Asilomar Accords, a meeting of animal shelter and comFrom the Department of Veterinary Pathology (Murphy, Frank, Petersen), Survey and Behavioral Research Services (Larson, Tyler), Center for Food Security and Public Health (Eia, Bickett-Weddle, Flaming), and the Department of Veterinary Clinical Sciences (Baldwin), College of Veterinary Medicine, and the Department of Statistics, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences (Kvam), Iowa State University, Ames, IA 50011. Supported by Maddie’s Fund, a Pet Rescue Foundation. Address correspondence to Dr. Petersen (kalicat@iastate.edu). 46 Scientific Reports CI ABBREVIATION Confidence interval munity professionals, with the goal of decreasing the rate of euthanasia of healthy and treatable companion animals.1 The health status nomenclature developed represents the only current, accepted standardization of health data collection and reporting across animal shelters. Our objective was to provide insight into the attitudes of companion animal owners toward medical and behavioral issues and the level of commitment they are willing to put forth to resolve these issues. These data would help animal shelters to determine at animal intake which less-than-healthy or behavior-deficient animals are the best candidates for medical or behavioral intervention strategies and placement via adoption. Materials and Methods Veterinarian survey—On July 16, 2009, a paper survey,a cover letter, and postage-paid return envelope were sent to a sample of 204 small and mixed animal veterinarians. The target population for the survey was practicing small and mixed animal veterinarians in the JAVMA, Vol 242, No. 1, January 1, 2013 Animal owner survey—In the summer of 2009, a random sample of household and cell phone numbers were selected to participate in a telephone surveya conducted by the Iowa State University Center for Survey Statistics and Methodology. Survey participants were identified via a random digit dial sample of Polk County, Iowa, and Story County, Iowa, landline and shared landline and cell phone telephone numbers provided by a commercial vendor.b Households that had owned at least 1 cat or dog within the preceding 3 years were invited to participate in the survey. It was requested that an adult responsible for making financial decisions pertaining to animal care and ownership complete the survey. Interviews were performed by trained interviewers employed by the Iowa State University Center for Survey and Statistical Analysis using a prepared script and question set, including questions concerning household demographics, number and type of animals owned, where the animals were obtained, frequency of and reasons for visiting a veterinarian, types and duration of interventions (treatments) the owner would be willing to use in the case of animal health or behavioral problems, amounts of money owner would be willing to spend to address hypothetical health concerns with variable projected levels of treatment success, and owner’s approach to recent animal health or behavioral problems and outcome and amount of money actually spent addressing these problems. Data analysis—To determine statistical differences in the way households responded to hypothetical questions, the following approach was used, depending on species in the household. For comparisons of dogonly versus cat-only or mixed species households, an ANOVA was used to test for differences among these 3 groups. The assumption that observations were independent within a group and across groups was met because these were all different households. The assumption that each group had the same variance was also met because the ratio of the largest to smallest sample variance was < 2 in all 3 hypothetical situations. The normality of the data within each group was also investigated. The data had a normal distribution as assessed via normal quartile plots. Subsequent to significant ANOVA comparisons, a set of confidence intervals were computed for differences between means of each set of survey response data. The specified familywise probability of coverage was set at 0.05. Intervals were based on the Studentized range statistic and the Tukey honestly significant difference method. All 2-sample and JAVMA, Vol 242, No. 1, January 1, 2013 paired t tests used to test hypotheses were performed at a significance level of 0.05 and did not assume equal variance (Welch t test). In the assessment of past negative treatment outcomes on predicted future behavior, a paired t test was used to account for the dependence structure. The assumption of normality was met in all cases. Commercial softwarec was used for all statistical analyses. Results Survey of veterinarians regarding owner response to diseases—To determine the attitudes of veterinarians and, through them, their clients concerning the manageability of various health and behavioral issues in cats and dogs, a sample of 204 small animal and mixed animal practice veterinarians were invited to complete a written survey. Of the contacted veterinarians, 97 eligible veterinarians completed the mail surveys (response rate, 47.5%), in which they were asked to categorize medical and behavioral conditions on the basis of their perception of what a typical client would do when presented with a diagnosis of any of the listed conditions in their companion animals. Category options were healthy, treatable, manageable, and unhealthy. Following compilation of responses to the survey, the authors placed each condition into a final category (healthy, treatable, manageable, or unhealthy) if > 50% of responding veterinarians were in agreement with a particular classification of a condition (Table 1 and data not shown). Conditions that fell under the category of treatable or manageable included many chronic disorders that would require client contributions of money or time to address, such as moderate shyness or separation anxiety, diabetes mellitus, mild to moderate elimination disorders, hyper- and hypoadrenocorticism, and autoimmune disease (data not shown). Several disorders were identified by > 50% of responding veterinarians as unhealthy, including severe aggression, severe elimination disorders, chronic renal failure, and debilitating osteoarthritis. Use of simple majority (≥ 50%) veterinarian agreement to delineate categories was chosen by the authors after reviewing the veterinarian responses and owner responses regarding willingness to use treatment modalities (Table 2) as well as reviewing the category definitions as described in the Asilomar Accords.1 Demographics of respondents and role of animal in household—To corroborate our findings provided by veterinarians in the same animal-owning population regarding approaches to various medical and behavioral diseases, 423 cat and dog owner interviews were completed regarding their past and hypothetical willingness to provide various treatments and interventions for their animals. Responses were obtained from 424 owners, which represented 90.0% of all owners willing to be screened and 37.9% of all households willing to be screened. One respondent did not complete the phone survey. The majority (68.8%) of all owners responsible for making financial decisions pertaining to their animals were female, and more than half (51.5%) of female respondents were within the range of 45 to 64 years of age. When asked about cats’ or dogs’ status within the household, 78.7% of respondents considered Scientific Reports 47 SMALL ANIMALS metropolitan area of Des Moines, Iowa. Multiple sources, including local and state veterinary associations, phone books, and investigator personal knowledge, were used to develop the sample frame, seeking to identify all relevant veterinarians in the geographic area. Surveys were sent to all individuals identified in the sample frame. The survey contained a listing of various behavioral and medical conditions, and respondents were asked to classify each condition as healthy, treatable, manageable, or unhealthy (untreatable or unmanageable), as adapted from Asilomar Accords1 definitions (Appendix) of these terms on the basis of their perception of their typical clients’ response to each condition. SMALL ANIMALS Table 1—Veterinarian (n = 97) classification of various diseases or conditions (categorized as behavioral or medical) into treatment categories based on what they thought most clients would consider healthy, treatable, manageable, or unhealthy (unmanageable or untreatable) in a survey of small and mixed animal veterinarians in Des Moines, Iowa. Respondents (%) Disease or condition Healthy Treatable Manageable Unhealthy Behavioral Mild to moderate phobias Mild to moderate shyness, with no aggression Mild to moderate separation anxiety Mild to moderate interdog or intercat aggression Mild to moderate territorial, protective, or resource guarding aggression Mild to moderate elimination disorder Mild to moderate fear or pain aggression Mild to moderate play aggression 4 26 5 4 1 1 2 6 36 43 39 17 23 41 26 42 60 32 55 74 70 53 67 47 0 0 1 3 3 3 4 4 Psychogenic alopecia (overgrooming) Mild to moderate dominance aggression Feral animal (eg, cat) Severe phobias Severe play aggression Severe separation anxiety Severe interdog or intercat aggression Severe fear or pain aggression Severe elimination disorder Severe territorial, protective, or resource guarding aggression Severe dominance aggression 5 1 23 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 24 19 24 7 5 5 1 2 4 2 2 64 62 31 65 57 55 40 36 35 28 12 5 15 18 24 32 33 52 57 57 63 82 Medical Pregnancy Limb disability (eg, single forelimb amputation) Geriatric with absence of medical or behavioral disease Severe autoimmune disease Severe congestive heart failure Debilitating osteoarthritis Severe cardiomyopathy Spinal cord injury Severe chronic renal failure Severe neoplasia FeLV or FIV infection with moderate to severe clinical signs Clinical feline infectious peritonitis 64 35 72 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 30 30 10 6 2 5 3 9 2 1 2 0 1 30 14 48 41 40 37 29 22 14 10 7 1 3 1 44 54 51 56 53 76 81 84 88 As a part of the veterinary survey, veterinarian respondents were provided a brief written definition of each category based on definitions modified from those developed as a part of the Asilomar Accords (Appendix). Table 2—Reasons for which owners would seek veterinary care for a cat versus a dog by percentage of households in a survey of 424 cat- or dog-owning households in central Iowa. Respondents (%) Reason for veterinary visit Cat Dog Vaccination Annual exam Serious illness Serious injury Other reasons 89.2 73.5 95.5 96.4 21.1 98.8 88.8 98.4 97.2 23.1 Other reasons category was a free-response option. For this open-ended response, owners specified services, including grooming, nail trim, sterilization surgery, dental prophylaxis, and boarding. the animal a member of the family, 20.6% considered the animal to be a pet or companion, and 0.71% considered the animal to be property (data not shown). Source of cats and dogs—Owners reported acquiring their animals from several sources, the most frequent of these being other persons (53.9%), pet stores (41.4%), and animal shelters (32.2%; data not shown). Individual households could and did report multiple sources for their animals. Among cat-only households (n = 102), 37.3% of households reported getting an animals from a shelter. More than half of cat-only households (58.8%) reported receiving an animal from some48 Scientific Reports one else, and 31.4% reported taking in a stray cat, in contrast to receiving an animal from commercial sources (breeder [3.9%] or pet store [5.9%]; data not shown). Among dog-only households (n = 200), 23.0% reported getting a dog from a shelter. Pet stores supplied animals to more than half of dog-only households (56.5%), in contrast to breeders (5.5%). Dog-only households also reported obtaining animals from someone else (44.0%) and by taking in strays (5.5%; data not shown). Reasons for seeking veterinary care—Survey participants were presented with a list of possible reasons for taking a cat or dog to a veterinarian and were asked to choose all that were appropriate. The percentage of households that would take an animal to a veterinarian for these various reasons was summarized (Table 2). Two hundred twenty-three (52.7%) owners responded to questions regarding cats and veterinary care, and 321 (75.9%) owners responded to questions pertaining to dogs and veterinary care. Notably, a higher percentage of households expressed a willingness to take a dog to the veterinarian than would take a cat to the veterinarian for the same reason. Respondents were invited to list other reasons for veterinary visits in a free-response question; these included grooming (n = 22), boarding (20), and nail trims (18) for dogs and spaying or neutering (n = 12), dental prophylaxis or treatment (10), and boarding (9) for cats. JAVMA, Vol 242, No. 1, January 1, 2013 Respondents (%) Treatment modality Give pills twice daily for 1 mo Give pills twice daily for rest of life Give eyedrops twice daily for 1 mo Give eyedrops twice daily for rest of life Take to veterinarian 2 times weekly for 3 mo to receive treatment Feed a special diet for 1 mo Feed a special diet for rest of life Give an injection once daily for rest of life Spend 10 min 3 times daily for 6 wk to train Very likely Likely Neutral Not likely Not at all likely 90.1 73.3 86.1 70.9 50.1 92 80.9 60.8 63.4 5.2 10.9 7.3 12.8 15.8 5.7 9 12.3 13 4.02 9 4.7 8.8 18.7 1.4 6.9 13 15.8 0.47 3.1 1.4 2.8 9.9 0.7 1.9 6.9 2.6 0.24 3.1 0.5 4.3 5 0.2 1.4 6.9 4.5 A random sample of household and cell phone numbers were selected to participate in a telephone survey.a Households that had owned at least 1 cat or dog within the preceding 3 years were invited to participate in the survey. It was requested that an adult responsible for making financial decisions pertaining to animal care and ownership complete the survey. Responses were obtained from 424 owners, which represented 90.0% of all owners willing to be screened and 37.9% of all households willing to be screened. Telephone interviewers listed several treatment modalities, and respondents were asked to specify on a scale of 1 to 5 (1 = not at all likely and 5 = very likely) the likelihood that the owner would perform a particular type of treatment if needed by their animal. Willingness to administer various modalities of care—To elucidate owners’ general willingness to treat subacute to chronic health or behavioral issues, survey participants were asked to rank the likelihood of administering a particular treatment on a scale of 1 (not at all likely) to 5 (very likely; Table 3). More than 70% of households reported a willingness (very likely) to administer treatments associated with various chronic conditions, including the administration of pills twice daily for the rest of the animal’s life (73.3%), eyedrops twice daily for life (70.9%), and feeding a special diet for life (80.9%). Fewer households responded that they were very likely to spend 10 minutes 3 times daily for 6 weeks to train an animal (63.4%), administer an injection daily for life (60.8%), or take an animal to the vet twice a week for 3 months (50.1%) for a treatment. Recent approaches to a seriously ill or injured cat or dog—Respondents were asked to reflect upon an animal that was seriously ill or injured within the preceding 3 years and were questioned about their treatment approach and outcome. Eighty-one respondents reported having had a seriously ill or injured cat, and 158 respondents reported having a seriously ill or injured dog within the preceding 3 years. Owners were asked whether they did any or all the following: watched to see whether the animal would get better, treated the animal at home, took the animal to the veterinarian, or did something else (free response; data not shown). Approaches were frequently used in tandem for ill or injured dogs and cats, with 98.7% of dog owners and 92.6% of cat owners reporting that they took their seriously ill or injured animal to the veterinarian, often after they watched the animal to see whether it got better (72.1% of dog owners and 66.7% of cat owners) and treating their animal at home (68.4% of dog owners and 66.7% of cat owners). Other approaches listed by respondents via the free-response category included implementation of special diet, euthanasia, delivery of body of deceased animal to veterinarian for disposal, burial of deceased animal in yard, and relinquishment of animal to local open-admission animal shelter. Reported outcomes by percentage of households, with multiple responses per owner occurring frequently for JAVMA, Vol 242, No. 1, January 1, 2013 multianimal households, included complete recovery (cats, 53.1%; dogs, 68.4%), some level of recovery (cats, 7.4%; dogs, 13.3%), still treating (cats, 14.8%; dogs, 11.4%), death of animal (cats, 61.7%; dogs, 39.9%), and gave animal away (dogs, 0.6%; data not shown). Willingness to spend money for hypothetical treatment outcomes—Respondents were asked to consider 3 hypothetical outcomes involving a young cat or dog with a serious illness or injury and how much they would be willing to invest financially for a particular outcome. Outcomes included a good chance of recovery, a 50:50 chance of recovery, and a poor chance of recovery (data not shown). For a good chance of recovery, 91.5% of respondents expressed a willingness to spend at least $100.00. For a 50:50 chance of recovery, 81.8% of respondents would spend at least $100.00. For a poor chance of recovery, 47.8% of respondents would spend at least $100.00 on treatment. Nearly onethird of respondents (31.0%) would spend > $1,000.00 for a good chance of recovery, 20.3% for a 50:50 chance of recovery, and 9.7% for a poor chance of recovery in these hypothetical situations. Approach to hypothetical scenarios for dog-only versus cat-only households—On the basis of findings from studies2,3 that determined that cat and dog owners spent different amounts on their respective animals, it was hypothesized that cat-only and dog-only households would differ in the amount of money they were willing to spend on a hypothetical young animal regarding the 3 hypothetical treatment outcomes. An ANOVA was run to identify the presence of significant differences in willingness of owners to spend on treating their animals, followed by a Tukey test to determine significance of these differences between cat-only, dog-only, and mixed animal households. As a part of the survey, respondents were asked to select which range corresponded to the dollar amount they would be willing to spend for each of the 3 possible outcomes. For ease of response and analysis, monetary spending intervals were each assigned a numeral between 1 and 5 as follows: 1 = < $50, 2 = $50.00 to < $100.00, 3 = $100.00 to < $500.00, 4 = $500.00 to < $1,000.00, and 5 = ≥ $1,000.00. If ensured a good treatment outcome, the mean response among all responScientific Reports 49 SMALL ANIMALS Table 3—Willingness to administer various treatment modalities by percentage of households in a survey of 424 cat- or dog-owning households in central Iowa. SMALL ANIMALS dents (dog-only, cat-only, and mixed animal households) was 3.79 (95% CI, 3.70 to 3.89), indicating that a typical household would be willing to spend > $100.00 for a sick cat or dog with a good chance of recovery. When looking at cat-only versus dog-only owners who were ensured a good hypothetical outcome, there was a significant (P = 0.003) difference in amounts that dog-only versus cat-only owners would be willing to spend on veterinary care, with the mean response for willingness to spend being greater for dog owners (3.96) than for cat owners (3.57). If ensured a 50:50 chance of recovery, the mean response among all respondents was 3.44 (95% CI, 3.35 to 3.55), indicating that a typical household would be willing to spend > $100.00 for a sick animal with a 50:50 chance of recovery. There was a significant (P = 0.002) difference in amounts that dog-only versus cat-only owners would be willing to spend on veterinary care, with the mean response for willingness to spend being greater for dog owners (3.65) than for cat owners (3.22). When given a poor chance of recovery, the mean response among all respondents was 2.53, (95% CI, 2.41 to 2.65), indicating that a typical household would be willing to spend at least $50.00 on a cat or dog with a poor chance of recovery. There was a significant (P = 0.025) difference in amounts that dog-only versus catonly owners were willing to spend on veterinary care, with the mean response for willingness to spend being greater for dog owners (2.67) than for cat owners (2.26). Actual reported veterinary expenditures involving a recently ill or injured cat or dog—To determine whether respondents’ responses to the hypothetical scenarios are a valid predictor of their actual behavior concerning a real animal, we performed an analysis of a subset of our animal-owning respondents (n = 231) who had taken their seriously ill animal to the veterinarian within the preceding 3 years and reported the outcome and cost of treatment. For owners who stated a specific approximate cost of treatment, the cost in dollars was recorded and used in analyses and also assigned to a monetary interval for the purpose of other analyses. For those owners who could not recall an exact number, they were asked to select a monetary interval in which they thought the expenditure had fallen. Monetary spending intervals were then assigned a numeral (1 to 5). This subset of survey respondents was then split into 2 groups: those respondents whose animals had a complete recovery and those whose animals had anything other than a complete recovery (partial but not complete recovery, still receiving treatment, or did not survive). When asked about actual recent veterinary expenditures, the mean response of owners whose animals had a complete recovery was 3.07, whereas the mean response of owners whose animals had anything other than a complete recovery was 3.49, indicating that typical households had spent at least $100.00 on treatment of their animals, but there was a significant (2-sample t test, P < 0.001) difference in amount spent between these 2 groups. Regardless of outcome, among owners who reported exact expenditures on a sick dog or cat, there was not a significant (2-sample t test, P = 0.169) difference in mean spending on veterinary services between dogs 50 Scientific Reports ($619.87) and cats ($447.12). Also, there was no significant difference in proportions of dog versus cat owners whose animal medical event spending was categorized in the 5 specified monetary intervals (data not shown). Even among owners who had stated exact expenditures of at least $500.00, the difference in mean expenditure on dogs ($1,365.88) versus cats ($1,152.94) was not significant (2-sample t test, P = 0.509). Assessment of past negative treatment outcomes on predicted future behavior—To determine whether past negative treatment outcomes influence owners’ predicted future behavior regarding veterinary treatment and expenditures, we again examined the responses of the subset of owners who had taken a sick or injured cat or dog to the veterinarian within the preceding 3 years and whose cat or dog had anything other than a complete recovery (n = 121). Specifically, we examined the responses of this subset of respondents to our hypothetical treatment outcome scenarios involving a hypothetical young animal (good chance of recovery, 50:50 chance of recovery, or poor chance of recovery) and the amount of money these respondents would be willing to spend if ensured that particular outcome. A comparison (paired t test) was then made between responses to the hypothetical outcomes and reported actual recent veterinary expenditures for a less than complete recovery. Numerals were assigned to monetary expenditure intervals (1 = < $50, 2 = $50.00 to < $100.00, 3 = $100.00 to < $500.00, 4 = $500.00 to < $1,000.00, and 5 = ≥ $1,000.00). The mean response when told that the hypothetical animal would have a good chance of recovery was 3.84, which was significantly (P = 0.001) different from the mean amount actually spent on a recently ill, real cat or dog (mean response, 3.49). When told that a hypothetical animal would have a 50:50 chance of recovery, the mean response was 3.46, which was not significantly (P = 0.937) different from what owners had actually spent on their real animal. Finally, when told that a hypothetical cat or dog would have a poor chance of recovery, the mean response was 2.62, which was significantly (P = P < 0.001) different from the mean of what was actually spent on a real animal. To look at the impact of negative outcomes on future spending in a different way, we assessed the willingness of owners to take a cat or dog to the veterinarian for any reason and whether this was negatively impacted by past experiences with a veterinarian-treated animal that had anything other than a complete recovery. We again analyzed the subset of owners who had taken a sick or injured cat or dog to the veterinarian for treatment within the preceding 3 years. Respondents were then divided into 2 groups (those whose animal had a complete recovery and those whose animal had anything other than a complete recovery), and responses to questions concerning willingness to take an animal to the veterinarian for various reasons (vaccinations, exam, illness and injury, or other) were assessed. For both dog and cat owners, there was not a significant (test for equal proportions; P ≥ 0.11 for all reasons for veterinary visits) difference in willingness to seek veterinary services between the group of respondents whose animals had recovered fully and those whose animals had not recovered fully (data not shown). JAVMA, Vol 242, No. 1, January 1, 2013 The present study found that in general, cat and dog owners indicated a willingness to use various treatment modalities and spend money on veterinary services when considering current or previously owned animals as well as hypothetical situations with an animal. Past experiences with veterinary care in which a cat or dog did not recovery fully did not diminish the willingness of respondents to use veterinary services again in the future. We suggest that these considerations can be used in conjunction with Asilomar Accords recommendations to assess adoptability of cats and dogs in animal shelters. Shelter workers may determine an incoming animal’s adoptability on the basis of what health or behavioral conditions the shelter is able to treat or address adequately with existing resources. However, the cat and dog-owning public may have the resources and willingness to treat an animal with these same health and behavioral conditions; thus, these conditions would not necessarily be impediments for adoption. In the present study, written and telephone surveys administered to veterinarians and cat and dog owners in central Iowa were designed to assess attitudes regarding what constitutes a manageable health or behavioral condition versus what constitutes an unmanageable health condition (one that may make an animal unadoptable). In the veterinarian survey, respondents were given a list of 120 actual medical and behavioral conditions and asked to categorize conditions according to what they thought the typical client judgment would be to each particular condition. Inherent in the veterinarian respondents’ assignment of a category (healthy, treatable, manageable, and unhealthy) presumably would be a consideration of cost to clients (both monetary and temporal) as well as client appeal or discomfort with various modalities of care (eg, injections and topical eyedrops). In a parallel animal owner survey, respondents were asked about specific interventions (eg, administration of pills or injections or performance of frequent training sessions) as well as associated costs to determine how much time (temporal cost), effort and money most owners within a specified geographic region (central Iowa) would be willing to expend in addressing cat or dog medical and behavioral issues. The purpose of the veterinarian’s survey was to classify actual conditions that may hinder the adoption of cats and dogs from animal shelters. We used this approach versus survey of people looking to adopt or adopting at animal shelters because typical adopters would not have the medical knowledge to make a decision regarding the health of an animal with a specific medical or behavioral disease. Animals regarded as unhealthy in this survey are likely to be very difficult to adopt from an animal shelter and may have such poor quality of life that euthanasia is the best option for these animals in a shelter situation. Animals judged as healthy are likely excellent candidates for adoption and should be easy to place. Animals with disorders classified by most veterinary survey participants as treatable or manageable (which includes chronic or serious illnesses and behavioral deficits) may also have JAVMA, Vol 242, No. 1, January 1, 2013 good prospects for adoption, provided that potential adopters are given the education and support needed to understand and address their animal’s unique needs. For 106 of 120 (88%) included conditions in the present study, a majority of veterinarians (> 50%) were in agreement concerning the classification of a particular condition. There was not veterinary agreement on 14 diseases, notably, with approximately equal numbers of veterinarians listing the disease as treatable versus manageable in some cases. Difference in veterinarian opinion as to whether an animal with a particular disorder can be returned to health or be provided a good quality of life with treatment is reflective not only of that veterinarian’s client population, but also of that particular clinician’s training, experience with various treatment modalities, and personal experience in treating a particular disease. The veterinarians’ collective classification of various diseases and its applicability to assessment of adoptability of animals in a particular shelter must be viewed in concert with an assessment of shelter resources and community attitudes and support, particularly in the case of special needs animals. The animal owner survey results supported the veterinarians’ assertions regarding which disorders or conditions owners would consider treatable or manageable, in that most cat and dog owners stated a willingness to expend the money and undertake the methods of care that would be required to treat chronic or serious health conditions. For example, at least 50% of veterinarians identified conditions such as mild to moderate diabetes mellitus, autoimmune disease, keratitis, or neoplasia as being treatable or manageable, and most owners expressed a willingness to use treatment modalities (give injections, pills, or eyedrops), make substantial financial commitments to veterinary care, and make frequent trips to the veterinarian to address chronic illness or injuries in their animals. It is important to note that animals affected by some types of disease, particularly highly contagious infectious diseases (eg, parvoviral enteritis), which may be treatable on an individual basis in an isolated setting (eg, veterinary hospital isolation ward), may put healthy animals at risk in a population (shelter) or foster home setting. Shelters will differ in their ability to address diseases of this type depending on availability of facilities and resources and will need to realistically decide whether animals with highly contagious diseases are in fact untreatable (and unadoptable) in their particular facility. Participants in the owner survey were residents of 2 Iowa counties, which according to the US Census Bureau American community survey 5-year estimates for 2005 to 2009,4 females comprised 51.3% (Polk County) and 49.0% (Story County) of the populations during this time period. The US population was estimated to be 50.7% female during the same time period.4 Among participants in this reported survey, 68.8% of self-selected decision makers for animals were female, significantly (P < 0.007) less than reported in a recent study5 of US pet-owning households (74.5%). More than half (51.5%) of the female respondents in our study were between 45 and 64 years of age. Of the persons living in Polk County and Story County, 24% and 18.8%, respectively, were between 45 and 64 years of age at the Scientific Reports 51 SMALL ANIMALS Discussion SMALL ANIMALS time of our survey; across the United States, 25.3% of the population fell into this age bracket.4 Consumers in this age bracket, primarily Baby Boomers, have been identified as “the best customers of veterinary services,” with householders in the age bracket of 45 to 54 years having a 40% greater mean expenditure on veterinary services.6 Marketing strategies targeting this population (ie, female Baby Boomers) may prove fruitful for shelters, particularly in the area of special needs adoptions, in which adopted animals will require a long-term financial and temporal commitment by the adopter in managing health or behavioral issues. Females in the age bracket of 40 to 59 years already make up the predominant volunteer pool at animal shelters.7 When asked about the role of the cat or dog in the household, the majority of respondents (78.7%) indicated that the animal was a member of the family, rather than a companion (ie, pet; 20.6%), or an item of property (0.71%) This distinction is important; animal owners who consider the animal a family member spend more on veterinary care and make more frequent visits to the veterinarian.2 To determine the willingness of animal owners to spend on an adopted animal, dog or cat owners were presented with several hypothetical treatment outcomes and asked how much they would be willing to spend to achieve the specified outcome. These data were compared with actual amounts owners spent on past serious veterinary medical problems with a similar outcome to the hypothetical situation. The hypothetical situation responses were very similar to animal owners’ real reported behaviors. Animal owners whose real animals had anything other than a complete recovery expressed a willingness to spend at least as much on a hypothetical animal as was spent on their real animal to ensure a 50:50 chance of recovery and were willing to spend even more on a hypothetical animal than was spent on a real animal to ensure a good chance of recovery. This indicates that past negative experiences do not substantially alter the willingness of respondents to invest again in veterinary care and may actually strengthen an animal owner’s resolve to pursue treatment that would have a fair to good chance of improving an animal’s health status following illness or injury. This finding implies a belief in the value of veterinary care and, at the same time, a realistic view of its limitations. It is important to note that animal owners’ responses to the survey are understandably different from what they might do for a yet unadopted animal in that these responses are influenced by owners’ feelings toward bonded animals. The level of commitment to an animal that has been in the household for several years is likely to be high and would therefore likely be accompanied by a high level of motivation to spend time and money to treat medical or behavioral disorders. Indeed, a recent study8 exploring owner-animal and clientveterinarian bonds demonstrated that the bond between animals and their owners has a large impact on owners’ willingness to spend money on veterinary care and that “care decisions were not necessarily made on the basis of the income of clients but rather on their attachment to their pets and their understanding of the importance and value of the recommendations of their 52 Scientific Reports veterinarians.” It is difficult to accurately assess the level of commitment that an animal owner may have for a potentially adopted animal. Therefore, the responses to the hypothetical scenarios are considered, at best, to be rough approximations of future behaviors involving shelter-adopted cats or dogs. If cat or dog owners are willing to make a major investment, both financial and temporal, in the treatment of their animals’ illnesses or behavioral deficiencies, this suggests that there are other reasons special needs animals are difficult to place. A recent study9 of adoptions from a large municipal animal shelter in Sacramento County, Calif, determined that dogs or cats that were relinquished to a shelter due to behavioral problems, being injured, or being old and sick were less readily adopted. Similar trends have been noted in the United Kingdom,10 and it is likely that a similar situation exists in the Midwestern United States, where the present study was conducted. The common perception is that potential adopters want young, healthy animals that will remain active and energetic for many years. However, the acquisition of an animal is only 1 reason that persons approach animal shelters when selecting a domestic animal companion; other reasons include a desire to help animals in need or to give hard luck cases another chance at a good life. To facilitate the adoption of special needs animals, shelters can provide comprehensive, point-of-contact information regarding the type of commitment required to manage various chronic health or behavioral disorder and conditions and develop promotional materials (posters or advertisements) emphasizing the positive aspects of each animal. Cat and dog owners have reported that they rarely (5% of dog or cat owners3) are provided with animal health information by animal shelter personnel. Potential adopters may not have previous experience with a particular illness or behavioral issue and may not have established a relationship with a veterinarian; therefore, animals may be passed over during shelter visits because of lack of access to immediate information regarding these problems. Providing kennel-side disease information sheets as well as the opportunity to talk with trained shelter volunteers or staff about a particular disease and its management could provide timely information and help dispel any misgivings or misinformation that may sway potential adopters away from special needs animals. Offering hands-on intervention instruction regarding administration of treatment modalities that owners may find intimidating (eg, giving injections or eyedrops) can help to build adopter confidence and comfort with treating their potential adopted animals. Educational seminars, hosted by shelters and conducted by partnering veterinarians, could provide a brief introduction to common chronic veterinary medical and behavioral disorders and their treatment or management, building a base of future clients and patients in need of care for a veterinary practice. In some communities, shelter resources are limited, but the animal-owning public may be found to be receptive to the level of financial and temporal commitment necessary to treat chronic disorders in animals. In all situations, but especially these, advertising JAVMA, Vol 242, No. 1, January 1, 2013 consider which animals are adoptable or unadoptable in their particular locale. a. b. c. Copies of the survey are available from the corresponding author upon request. Survey Sampling International, Shelton, Conn. R, version 2.15.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available at: www.r-project.org/. Accessed Aug 20, 2012. References 1. Asilomar Accords. Available at: www.asilomaraccords.org/2004accords5.pdf. Accessed Aug 20, 2012. 2. AVMA. US pet ownership and demographics sourcebook. Schaumburg, Ill: AVMA, 2007. 3. American Pet Product Manufacturers Association. 2007–2008 APPMA national pet owners survey. Greenwich, Conn: American Pet Product Manufacturers Association, 2008. 4. US Census Bureau. American community survey 5-year estimates for 2005–2009. Data profile, Iowa. Available at www. census.gov/acs/www/. Accessed Aug 19, 2012. 5. Shepherd AJ. Results of the 2007 AVMA survey of US pet-owning households regarding use of veterinary services and expenditures. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2008;233:727–728. 6. The New Strategist Editors. Who’s buying for pets. 6th ed. Ithaca, NY: New Strategist Publications, 2008;50. 7. Neumann SL. Animal welfare volunteers. Who are they, and why do they do what they do? Anthrozoös 2010;23:351–364. 8. Lue TW, Pantenburg DP, Crawford PM. Impact of the owner-pet and client-veterinarian bond on the care that pets receive. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2008;232:531–540. 9. Lepper M, Kass PH, Hart LA. Prediction of adoption versus euthanasia among dogs and cats in a California animal shelter. J Appl Anim Welf Sci 2002;5:29–42. 10. Diesel G, Smith H, Pfeiffer DU. Factors affecting time to adoption of dogs re-homed by a charity in the UK. Anim Welf 2007;16:353–360. Appendix Definitions used in a survey asking small and mixed animal veterinarians in Des Moines, Iowa, to rank medical or behavioral diseases or conditions on the basis of what they thought most clients would consider to be healthy, treatable, manageable, and unhealthy (unmanageable or untreatable). Classification Definition Healthy Treatable Manageable No signs of disease or any behavioral problems Not currently healthy but likely to become so if given medical or behavioral care Not currently healthy and not likely to become healthy even with treatment, but would maintain a satisfactory quality of life if given appropriate care Dangerous or intractable behavior issues or medical problems that cannot be managed or resolved with treatment Unhealthy (Adapted from the Asilomar Accords. Available at: www.asilomaraccords.org/2004-accords5.pdf. Accessed Aug 20, 2012.) JAVMA, Vol 242, No. 1, January 1, 2013 Scientific Reports 53 SMALL ANIMALS campaigns profiling individual special needs animals may assist shelters in obtaining financial donations necessary for the provision of medical or behavioral interventions while the animal is maintained in the shelter or foster home awaiting placement in a permanent home. To determine which animals may benefit from such interventions versus those for which an illness, injury, or behavioral deficit would be impediments to adoption, regional sheltering groups are encouraged to use surveys, potentially similar to those used in the present study, for their particular region. In this situation, animals deemed unadoptable within a region could be transferred to shelters in more receptive regions. Results of the surveys described in the present report provide a profile of cat or dog owners in central Iowa and demonstrate a congruency in thought between cat and dog owners and veterinarians as to which medical or behavioral conditions may prove to be a hindrance to home placement of affected animals. The study identified a high level of public receptiveness to the treatment of many chronic disorders in dogs and cats and use of treatment modalities and financial commitments necessary for this. It is clear that within this region, efforts to promote special needs adoptions may prove fruitful; many animals with chronic conditions that were previously considered unadoptable may have good adoption prospects, provided that potential adopters are provided the information needed to make an informed decision. Similar studies in other geographic regions will help animal shelters to determine community attitudes and enable those shelters to re-