kubla khan

KUBLA KHAN

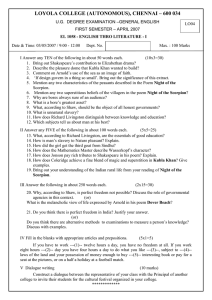

IMAGERY IN SAMUEL TAYLOR COLERIDGES KUBLA KHAN

Thesis statement In the Samuel Taylor Coleridges Kubla Khan imagery is used as a means of achieving a dreamy and somewhat surreal quality to the poem other than this, it is also used to make the poem more vivid because most of what is described in the poem are mythological or fictional, so imagery makes these immaterial objects more tangible for the reader.

Unlike in the visual arts, literature lacks what is known as visual stimulus. To compensate for this lack, literature uses a tool known as imagery. Imagery is the means by which words, whether in fiction or poetry, work to initiate the creation mental images. In poetry, the mind is left with the job of creating images to support what is being said in the text. Essentially, poetry has some aspect of interactivity in that it does not spoon feed the audience but leaves some aspects of its appreciation for the audience to create. More importantly, imagery plays various roles in poetry and each of these roles achieve a particular end which is always intentional as poetry needs to be purposive. The poet is always aware of what heshe wants to achieve in hisher poetry and consciously uses devices to achieve these intentions. In the Samuel Taylor

Coleridges Kubla Khan imagery is used as a means of achieving a dreamy and somewhat surreal quality to the poem other than this, it is also used to make the poem more vivid because most of what is described in the poem are mythological or fictional, so imagery makes these immaterial objects more tangible for the reader.

On the matter of achieving a dreamy and surreal quality to the poem, imagery in effect sets the tone for the poem. This means that as opposed to making the poem bland and lacking of character, imagery gives it an identity or a personality on its own. This is evident in a few of the lines from the poem which use imagery to achieve the dreamy or surreal feel, or more formally the tone of the poem. For instance, we have the line, Through caverns measureless to man Down to a sunless sea (5-6) which describes where Xanadu is located. Here we see that the lines present an image of an eternally deep cave where an underground sea exists. While the underground sea is believable, a cavern or a cave that cannot be measured by human technology is something that is out of the ordinary and defies the laws of nature. So, instead of viewing a regular, ordinary underground lake located within a cave, the reader would see a dark fathomless abyss in hisher minds eye. This image serves to situate the setting of the poem to be somewhere that does not actually exist on earth but probably only in dreams or the imagination. Another interesting line in the poem that achieves this same tone for the poem is, And there were gardens bright with sinuous rills, Where blossomed many an incense-bearing tree. (9-10)

Again, this line offers contrasts of realistic imagery and mythological imagery. What a reader sees here is a beautiful garden and in that garden there are incense-bearing trees. Of course, as the rule of metaphor dictates, the image has first to be true on the literal level before it can be true on the metaphorical level and this rule of thumb may apply to this line in that it could represent trees bearing fragrant flowers. However, because of the use of incense which is a ceremonial implement, and with the common knowledge that incense does not grow on trees and is derived from the sap of trees, one is given the mental image that the tree actually bears fruit that burns to release an incense-like scent. This particular image gives the line an unnatural tone and therefore achieves the tone that the poet would like to achieve.

Now, to the matter of imagery making the immaterial more tangible to the reader, the poem too has a slew of textual evidences to this effect. The line, A mighty fountain momently was forced Amid whose swift half-intermitted burst Huge fragments vaulted like rebounding hail, (19-21) for instance, the first image that comes to mind is that of a powerful geyser that shoots up to explode with shards of ice flying through the air, but this does not become consistent with the place referred to in the poem located underground in a deep, unfathomable cavern. Hence, this geyser becomes immaterial or impossible but because of the way it is presented and with the vivid description of this particular phenomenon it becomes more tangible to the mind of the reader. Another line that has the same effect is, Through wood and dale the sacred river ran, Then reached the caverns measureless to man, And sank in tumult to a lifeless ocean

(26-28) Taking this particular line in the context of the unfathomable caverns, one would easily wonder, how could the poet know that the rivers reached an area that was not accessible to man So, with this question in mind, the line becomes immaterial but because of the images conjured in the line, these being a river flowing endlessly terminating in an ocean that is lifeless, the reader can easily associate the line with something that exists in real life and so gives it its intangibility or concreteness.

Based on the textual evidence presented it is clear that in the poem Kubla Khan by Samuel Taylor Coleridge imagery is able to achieve two major things that are necessary to poetry, one is tone and the second is concretization. These two elements of poetic expression serve to make the poem accessible to the reader and therefore bring down the elite art of poetry to a level easily appreciated by the ordinary reader.

The most striking of the many poetic devices in “Kubla Khan” are its sounds and images. One of the most musical of poems, it is full of assonance and alliteration, as can be seen in the opening five lines:

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

stately pleasure-dome decree:Where Alph, the sacred river, ranThrough caverns measureless to man Down to a sunless sea.

This repetition of a, e , and u sounds continues throughout the poem with the a sounds dominating, creating a vivid yet mournful song appropriate for one intended to inspire its listeners to cry “Beware! Beware!” in their awe of the poet.

The halting assonance in the line “As if this earth in fast thick pants were breathing” creates the effect of breathing.

The alliteration is especially prevalent in the opening lines, as each line closes with it: “Kubla Khan,” “pleasure-dome decree,” “river, ran,” “measureless to man,” and “sunless sea.” The effect is almost to hypnotize the reader or listener into being receptive to the marvelous visions about to appear. Other notable uses of alliteration include the juxtaposition of “waning” and “woman wailing” to create a wailing sound.

“Five miles meandering with a mazy motion” sounds like the movement it describes. The repetition of the initial h and d sounds in the closing lines creates an image of the narrator as haunted and doomed:

His flashing eyes, his floating hair!Weave a circle round him thrice,And close your eyes with holy dread,For he on honey-dew hath fed,And drunk the milk of Paradise.

The assonance and alliteration soften the impact of the terminal rhyme and establish a sensation of movement to reinforce the image of the flowing river with the shadow of the pleasure dome floating upon it.

The imagery of “Kubla Khan” is evocative without being so specific that it negates the magical, dreamlike effect for which Coleridge is striving. The

“gardens bright with sinuous rills,” “incense-bearing tree,” “forests ancient as the hills,” and “sunny spots of greenery” are deliberately vague, as if recalled from a dream. Such images stimulate a vision of Xanadu bound only by the reader’s imagination. Coleridge has described how as a young man in poor health he took a prescribed drug. While reading a popular travel book, he fell into a deep slumber and “dreamed” the poem in which a Mongol emperor orders a “stately pleasure dome” near a sacred river that has cut a deep chasm into the earth on its way to the sea.

Two thirds of the poem’s 54 lines describe this strange setting. Then follows a vision of “an Abyssinian maid” whose song would serve the speaker--if only he could revive it--to reconstruct the exotic scene.

One theme of the poem is the nature of poetic inspiration. Coleridge makes use of the ancient tradition that poets are literally not themselves when composing but are possessed by a daemon or guiding spirit. The poet cannot control the daemon, only try to take advantage of it when it comes. This poem paradoxically voices the frustration of a poet whose daemon has departed.

“KUBLA KHAN” has attracted much criticism, including a classic study by John

Livingston Lowes, THE ROAD TO XANADU. Some critics have accepted

Coleridge’s explanation of an unconscious or semiconscious origin while others have pointed to the poet’s extraordinary command of meter and other sound patterns and even have discerned a logical structure that only a conscious and disciplined artist could achieve. To such critics, Coleridge is providing a carefully crafted picture of a wild creator with “flashing eyes” and

“floating hair.”

Whether the poem displays or only simulates wild inspiration, whether the poet is out of his mind or fully in control, “KUBLA KHAN” is a magical poem with a verbal richness approached only a few times by Coleridge and not often by any poet.

THE RIVER ALPH

Symbol Analysis

This big, dramatic river takes over most of the first half of the poem. Our speaker is a fan – he seems to be constantly drawn back to the river. Descriptions of the river largely focus on how powerful it is. It gives us the poem's main images of the force and excitement of the natural world. While other places may be quiet or safe or calm, the river is noisy, active, and even a little dangerous. It is also always moving, traveling across the poem and across the landscape from the peaceful gardens to the faraway sea.

Line 3: The river is specifically introduced here, the only time its name is mentioned. The name Alph may be an allusion to the Greek river Alpheus. This connects us to a whole world of classical literature, art and history that was important to English poets.

Lines 21-22: Here the river surges up in a huge fountain, and it's so strong that it tears up pieces of rock and throws them along with it. The speaker wants us to understand this power, so he uses a simile, comparing the rocks to "rebounding hail." For added emphasis, he offers another simile in the next line. This time the comparison is with the process of "threshing." When you harvest a grain like wheat, you need to separate the part you can eat from the part that covers it, which is called the chaff (that's why he calls the grain "chaffy" in line 22). In

Coleridge's time, you would do this by beating the grain with a tool called a

"flail." This would loosen the chaff and make it easy to remove. So when you hit that grain, it would bounce and tumble around like the rocks in the raging River

Alph.

Line 25:This poem has little moments of alliteration all over the place, but this is a big one. All the major words in this line start with "m." The murmuring sound of these words picks up the lazy, slow-moving feeling of the river at this moment in the poem.

THE OCEAN

Symbol Analysis

When it shows up in the poem, the ocean is a gloomy, mysterious and far-away place. Nothing in particular happens there, except that it marks the end of the river. It's a dead-end, a place where there is no life or light. The other settings in the poem tend to be active and alive. The forest is sunny, the river is noisy, the dome is warm, even the caves are deep and icy. The ocean, however is just an empty, open space. It might make us think a little bit of the Underworld, a place where things simply end.

Line 5: Our first image of the ocean emphasizes the absence of light. It's a place where no sun shines, far away from the "sunny spots" we will see in line 11. The alliteration of the two "s" sounds also adds to the sense of mystery and emptiness, and gives this short line a slithery, sinister, sound.

Line 28: Here it is the absence of life that becomes the most important part of this image of the ocean.

Line 32: In this line, the ocean is a blank canvas. The shadow of the palace floats on it, but we don't have any sense that it has a life of its own.

XANADU - A.K.A. THE PLEASURE DOME

Symbol Analysis

This might sound a little more exciting than it really is. As far as we can tell, it just means a big, especially nice palace, with pretty gardens all around it. The dome is a safe, sunny, happy place. In the poem, it stands for all the majesty and the triumph of mankind, since it's the house of an emperor. However, when it is compared to the power and the immensity of nature, it might not seem so big after all.

Line 1: This is the only time the name of the palace is mentioned. This dream version of Xanadu is an allusion to a real historical place, built as a summer palace in what is now called Inner Mongolia. Marco Polo visited it, starting a legend that filtered all the way down to Samuel Coleridge in England.

Line 2: Let's talk for a second about this "dome." What are we supposed to see in our heads when Coleridge uses that word? We'd guess that it's not meant to be just a dome hovering in space or an empty shell. The dome is his way of referring to the legendary palace of Xanadu. When you use one feature of a thing to refer to the whole, that's called synecdoche.

Line 31-32: This comes up in a few places, but here the dome is a symbol for the work of mankind, set against the natural world. The "shadow of the dome…on the waves" contrasts a building with the wild, unknowable power of nature - a major theme in this poem.

THE CAVERNS

Symbol Analysis

The caverns are huge, frightening, cold, and fascinating to our speaker. They appear in the poem for just a moment at first, as the place the river passes through. As things move along, however, we start to see that these caverns are important in this poem. They are the opposite of the warm, happy palace. They are dramatic, freezing, underground, and represent everything the pleasure dome is not.

Line 4: The phrase, "caverns measureless to man," is a good example of hyperbole. The speaker could say that the caverns are "really deep" or "you can't see the bottom." Instead, the depth of the caverns is exaggerated to an infinite point, adding to the feeling of mystery. In the real world, any cavern could eventually be measured, no matter how deep. So what and where are these strange caves?

Line 27: Here we see the caverns again, described in exactly the same way:

"measureless to man." The repetition of this phrase emphasizes their importance and drives home their sense of mystery and depth.

Line 47: When they are contrasted with the sunny dome like this, the caves of ice becomes a symbol of the forces of nature that lie under and surround the works of man. We keep mentioning this because Coleridge keeps pushing it into view. The clash of these forces is one of the main points of this vision.

THE WOMAN AND HER DEMON LOVER

Symbol Analysis

This one comes and goes fast, but it's a really powerful image. The line calls up feelings of supernatural power, romance and excitement. A waning moon and the spooky chasm all help set a scene that is wilder and more foreign than what we've already seen in the poem.

Line 16: There could be a whole other poem or even a novel in here, built around the image of this wailing woman. We get just a taste of the drama of her story, but it helps to set the mood of this landscape. Check out the way that adding the word "demon" changes and deepens this image. If she was just wailing for a plain old "lover," that would be sad, but not nearly so strange and exciting.

ANALYSIS: SETTING

Where It All Goes Down

Xanadu, during the reign of Mongol emperor Kubla Khan

Coleridge has a lot to say about the setting of this poem. He devotes many lines to describing the landscape, the caverns, and the sea. That works for the first half of the poem, but then that Abyssinian maid shows up, and then there are the flashing eyes, and the milk of a paradise. All this new stuff makes it hard to believe we're still in the same place as the river and the palace. Maybe we need a setting that can encompass this whole experience.

So here's what we think: This poem could take place in a kid's bedroom.

Remember that age when you were really excited about faraway places and legends and monsters? Imagine Coleridge as your cool uncle who told you amazing, spooky bedtime stories. "Kubla Khan" is sort of about a person and a place, but it's really more about how you can create those things with words alone. That's the heart of the bedtime story. You didn't need pictures or movies or a plane or any other props. Coleridge needed sleep and sickness and drugs in order to have this vision. But the amazing thing about this poem is that he can recreate this experience without any of those things. He just needs the sound and the texture of words. So, imagine yourself tucked in on a rainy night in winter, just a candle lighting the room, listening to Coleridge build castles with his words.

ANALYSIS: WHAT'S UP WITH THE TITLE?

The main title of this poem is just plain "Kubla Khan." It's a pretty great name, isn't it? Sounds tough, mysterious, and exotic. We're willing to bet that Coleridge wanted that name to echo in a big way, to call up associations and feelings. It sets a tone for the poem, since the title transports us to another place and time before we even get started. But there's another piece. The full title is: "Kubla

Khan Or a Vision in a Dream. A Fragment."

Orientalism: Kubla Khan’s Often Overlooked Racism

Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s famous poem Kubla Khan is remarkable and well renowned for many reasons, but while it is a great example of The Romantic

Period’s style of poetry, sadly it is also a great example of the racist ideas that many Western, white, people had about anyone from the Eastern part of the world. Through word choice and imageryKubla Khan evokes an exotic and sensual tale that is clearly not about English society, but about the English ideas of what the East must be like. In Kubla Khan there are repeated offensive remarks made about Eastern people, especially towards Eastern women. Because of this, Kubla Khan is a great example of the all too popular theme of Orientalism in Romantic Literature, which is the stereotyping of all

Eastern people as being extremely sexual and erotic (in a fetish like manner), being mystical and exotic, and also of being “demon-like” or supernatural. There is no differentiating between any of the Eastern nations and instead these stereotypes are applied to anyone who comes from anywhere East of

Europe. Because of this Orientalism is a form of racism, that sadly gets overlooked.

The first hint of Orientalism seen in Kubla Khan is in line 6 when the magical and

Eastern inspired realm of Xanadu is described as being “five miles of fertile ground (Coleridge)”. Of course, Xanadu is not an English word and instead sounds like a Western man’s idea of what an Eastern place would be called, thus stereotyping all Eastern languages. This is also the first of many sexual references in this poem which alludes to the idea of Eastern women being very sexual and fertile. The emphasis on the word “fertile” in this line has a very strong sexual connotation which evokes the idea of female sexuality. Yes, maybe the ground and earth really are fertile, but supposedly so are the women of this magical Eastern land. Fertility, of course, is a highly desired item in women for men, so this makes Eastern women seem all the more valuable in regard to their sexuality. This line is then followed up by line 9 where it’s mentioned that there are “many an incense-bearing tree (Coleridge)”. Incense, of course, is a very sensual and mystical item, which further creates the image this erotic and magical Oriental realm. Incense is a rich and sought after product that comes from the East, so no fantasy depiction of an Eastern land would be proper without it. By beginning the poem with the mentioning of fertility and incense, it sets the stage for the rest of the sexual references that are yet to come.

The second instance of Orientalism in Kubla Khan are in lines 14, 15 and 16 where there is “A savage place! As holy and enchanted/As e’er beneath a waning moon was haunted/By a woman wailing for her demon-lover!

(Coleridge)”. Xanadu is described as being enchanting but also savage and holy, all three of these words support the ideas of Orientalism, since they each carry an important connotation, savage being animal-like, holy being mystical and enchanting being exotic. It is also important to note that the following line says Xanadu is haunted, also supporting all the supernatural beliefs of

Orientalism. To even further this stereotyping, of course, no Western man would refer to a Western woman in a poem as crying out for her “demonlover”. No respectable, every-day, English woman would do such a thing, yet an

Eastern woman is depicted doing so because it was believed that not only were

Eastern people “demon-like”, but also infatuated with sex. This is an incredibly racist depiction of Eastern women, since they do not have demon-lovers, just like English women don’t. Had it been an English man this woman was calling out for in the poem, he would not have been described as being demon-like, so this line implies that the men these Eastern women love are not humans but devils. This takes away the humanity of both the woman in this poem and her lover. This lack of humanity allows for racist ideals to continue, since they aren’t considered fully human, but rather are depicted in this line as demon-like or even animalistic. The way the woman is described as wailing out into the night brings in a wild and beast-like element, just like many animals call out in the dark to their mates, this poor woman is depicted doing the same, making her appear uncivilized. Instead of a reserved and mild English woman, she’s created to be a passionate and sex-crazed non human.

Kubla Khan carries on with the racist Orientalism in lines 29 and 30, where “And mid’ this tumult Kulba heard from far/ancestral voices prophesying war!

(Coleridge)”. This is one of the strongest examples of the supernatural element and mysticism in the poem. By calling them “ancestral voices” it makes them out to be ancient and magical, even ghostlike. These voices do not belong to people who are alive and well. There is an eery feel to these lines, they are not bringing good news. On top of that, not only are there ghost voices talking to

Kubla, but they are warning about there being a war. This brings back the element of violence and of the people being wild and untamed. This Eastern land is made out to be a very uncivilized place since there are crazy voices from afar speaking of wars. Instead of glorifying and explaining the cause for the violence, which would be done if it were Western men mentioning the start of a war, these voices are set up to be scary and create an uneasy feel in the poem. By the sudden reference to these voices it shows how unpredictable this land is, just like the poem is unpredictable in its story, so too is this Eastern land. There is no telling what will happen next!

Lastly, another strong example of Orientalism is seen in lines 43 and 44, where a woman from a vision is spoken of, “Her symphony and song/to such a deep delight ‘twould win me (Coleridge)”. This woman is more than likely meant to be an Eastern woman and is appearing to the speaker in a supernatural vision or

some sort of fantasy, making her unreal and magical. The speaker is convinced that she would win him over due to her songs alone. While this image isn’t nearly as sexualized as the previous depictions of a woman, it still expresses the idea that these non-Western women are charming to men and easily tempt and seduce them. Apparently for the speaker all it would take is a simple song from this lady to make him hers. This makes the woman mystical and definitely exoctic, since she’s no ordinary woman that could be found in England. While this scene isn’t a derogatory image of her, it once again stereotypes all Eastern women into all being alluring and seductive, plus that fact that she is appearing in a vision bring back the idea that all of the East is a superstitious and unnatural part of the world.

To summarize, Orientalism is often overlooked as a form of racism because it is not as prominent in culture as other forms of racism, but it is still there and it is always unacceptable. Kubla Khan is racist towards anyone of Eastern descent because it creates a fantasy land with fantasy people that in reality have never existed. While there’s nothing wrong with creating a fantasy, it is wrong when

Kubla Khan bases all of it (especially derogatory aspects) off of thousands of real people and hundreds of real and unique nations. Kubla Khan is a famous

Romantic poem, but should be noted that it is also a famous racist poem. The subtle forms of racism are the worst, because they are so easily brushed under the rug or overlooked by people who do not want to see it. Coleridge was from a society that saw nothing wrong in embracing the stereotypes and generalization of minorities, but that never made it alright. Through the blatant derogatory and stereotypical aspects of Kubla Khan, the horror of Orientalism will not be forgotten anytime soon. exoticism of Kubla Khan .

Writers often create a feeling of otherness by making exotic references. The exotic can be simply defined as a description having the characteristics of a distant foreign place. Western knowledge about the world beyond Europe originally came from explorers and tradesmen who returned with stories of remarkable places and people with strange habits and customs. The most unfamiliar settings and cultures often inspired the greatest interest. By the time of the Romantic period, poets would recreate exotic worlds as an expression of their heightened imagination. Some of these writers used drugs, which they felt would induce glimpses of the exotic.

Coleridge

was one such writer; he may even have exaggerated his drug use as a means of selfpublicity given readers’ fascination with the idea of the heightened creativity of the drugged genius.

Under the influence of opium

Coleridge originally took opium in its medicinal form, Laudanum, to alleviate the pain in his knees, which had kept him bed-ridden for several months. His sustained use created a dependency but also, he believed, inspired his verse; to such an extent, in fact, that the absence of drugs deprived him of inspiration as in the wellknown account of the writing of ‘

Kubla Khan

’. Coleridge claimed that the poem had come to him while under the influence of opium, but that his creative vision was interrupted by a man from the village of Porlock who knocked on his door about some business. By the time their exchange had ended, almost an hour later, the vision had fled, and when Coleridge returned to the poem he could record no more of it. Academics may have argued about the reliability of this story, but the man from Porlock now exists as a metaphor of daily realities undermining creative genius.

Exotic qualities

‘Kubla Khan’ may have been embarked upon after a drug induced state but it has been carefully crafted despite its fragmentary nature. There is a clearheaded line-byline mastery and control of poetic forms, not least Coleridge’s deliberate use of exotic language and imagery to help him create a powerful sense of otherness. The poem’s exotic qualities are present from the opening line, which is incredibly charged and emphasises two Eastern names. The syntactically wrought nature of the opening energises the force of these names: the opening could read, ‘Kubla Khan decreed that a stately pleasure-dome be built in Xanadu’ but Coleridge instead states, much more memorably: ‘In Xanadu did Kubla Khan / A stately pleasuredome decree …’ We do not know who Kubla

Khan is or his motive for building the dome, and this lack of knowledge allows us to focus on the fabulous construction. Alongside these decontextualised names is that of the river, Alph. Many critics believe that Coleridge is referring to Greek river Alpheus. If this is the case he is positioning our imaginations both in the

Classical past of Europe and the past of the East through references to Xanadu, the palace of a Mongol ruler, and Kubla Khan, emperor of China.

Kubla Khan as an Illustration of Romanticism.

Or,

Romantic elements in Kubla Khan.

Answer:

The Romantic lives in a world, not of things, but of images; not of laws, but of metaphors. Although best known for his poetry, Samuel Taylor

Coleridge was also an important literary critic who helped to popularize the

Romantic Movement among English speaking peoples. Romanticism had emerged from the German Sturm und Drang movement of the second half of the eighteenth century, which itself had arisen as a reaction to Enlightenment philosophy and values. Whereas Enlightenment thinkers envisioned an orderly universe and advocated for the use of reason as guide for productive living, the

Sturm und Drang called for a passionate approach to life in a world more sensual than sensible.

The Romantics, while maintaining distance from the objective rationalism of the

Enlightenment, also distanced themselves from the impetuousness of Sturm und

Drang. They focused on a subjective view of reality that, while transcending the strictures of logic and reason, also avoids complete domination by ungoverned emotionalism. For the Romantic, meaning is best found through the use of imagination rather than strict adherence to calculation or passion. Coleridge’s critical essays and his poetry, especially “Kubla Khan,” serve as a Romantic

counterargument to the ideals of the Enlightenment as described by Emmanuel

Kant in his seminal essay “What is Enlightenment?” Indeed, “Kubla Khan,” in its very form and message, illustrates the Romantic principles that Coleridge advances in his criticism.

The fundamental assumption of the Enlightenment was that there are universal truths and laws to which the human mind is naturally able to aspire. The universe, they believed, operated on rational principles, and humans, as products of the universe, may function rationally and productively within the world as long as we are not dominated by social structures built upon superstition or mysticism in the service of authoritarian power. The aim of

Enlightenment philosophy was to create and promote political structures in which the subjects and citizens of nations are free to guide themselves toward the universal laws and thus influence their own political structures for the betterment of humankind in general rather than simply for the benefit of an elite ruling class. Underlying the philosophical assumptions and political aims of the

Enlightenment is the belief that the universe and humankind are both fundamentally rational similarity, and the result is inadequate or as Coleridge would say, “disgusting” and “loathsome.”

A fruitful analysis of “Kubla Khan” does not center on finding concrete correlations between Coleridge’s images and the real word or in dismissing it as a simple dreamed-up fragment. The focus must be on discovering the meaning behind the images —but more so on the meaning of Coleridge’s use of his images. Only by understanding Coleridge’s use of image can a reader understand his commentary on Romanticism. The central image, arguable, is the river. It lies beneath the surface world, but it is not passive. It affects the

Khan’s world even before it erupts. As Humphrey House argues, “The fertility of the plain is only made possible by the mysterious energy of the source *the river+” (House 307). The river, as symbol of the subconscious and of the profound meaning within the metaphor, is the essential fructifying force in the

Khan’s world. Coleridge implies as much by naming it the Alph, which brings to mind the first letter of the Greek alphabet (Bahti, 1043). The river is the first thing. Although it might be a stretch, it may be worth noting that the name of the

Khan’s realm of Xanadu begins with chi, which appears not last, but certainly much later in the Greek alphabet. Typical interpretations of “Kubla Khan” vary from a fanciful, opium-induced nature poem to an exposition of the creative process. However, it contains a deeper commentary on the differences between the Enlightenment and Romantic views of the world. Coleridge begins with an exposition of the Enlightenment view of the world. Kubla Khan has (or so he believes) bent nature to his will to create an earthly paradise. He has encompassed and enclosed the surface world to consolidate his seat of power.

Like Enlightenment thinkers, Kubla has engaged the world of visible things — trees, gardens, walls, and towers —and believes he has thus entered into accord with nature. He has taken what he can see for all that is. When the underground river erupts into his world, he experiences it as an ominous intrusion. The fountain disrupts his order, and he can only see it as a harbinger of violent chaos. Like an Enlightenment thinker, for the Khan up must be up, down must be down, and all must remain within ordered boundaries. Analyzing the other proper names in the poem reveals more clues about Coleridge’s intention regarding his images. Both “Abora” and “Abyssinian” begin with the prefix ab-, which in the Latin means “from.” These names indicate that both the maiden and her song serve as sources of energy and meaning. The singer shares metaphorical roots with the sacred river; they share qualities of traditional

Chinese Yin imagery: darkness and femininity as well as associations with water and the subterranean. Coleridge seems to be associating the singing damsel with the sacred river and positioning both as wellsprings of energy. Indeed, the poem proves out those associations out. The river erupts to the surface and brings prophesy to Kubla Khan, while the singer infuses the poet with the dreadful holy power of art. Coleridge goes even deeper in his commentary on

Romantic principles. Contrary to what critics like Cooper think, the poem is not about any real place. Reflecting the idea that we live in a world of images and not things, the very subject of the poem is image, and Coleridge juxtaposes image upon image to emphasize the point. Coleridge tells the reader in his introduction that he experienced the poem as a vision. The poem itself is about that vision, and he describes the purported loss of the vision as “images on the surface of a stream into which a stone has been cast” (Coleridge 377).

In the Romantic worldview, as Coleridge argues, art cannot be an imitation of a thing but only the image of a thing. The projecting of image upon image is best seen in lines 31 through 34: The shadow of the dome of pleasure Floated midway on the waves; Where was heard the mingled measure from the fountain and the caves. It is in this rupture of order and reason in which the river absorbs within itself the likeness of the dome, that the Khan experiences the breaking of his rational world and is subjected to the profound powers of the deep.

Taken together, Coleridge’s introduction and poem are a self-referential unity.

The introduction is a supposedly rational explanation of the poem, while the poem is a collection of words that attempt to reproduce the power of the original vision, which, in turn, (like the sacred river) has erupted unbidden from the subterranean depths of the poet’s mind. Like the world of the Romantic, there is no concrete source for anything. Words simply refer to other words which refer to the memory of a vision that appeared in a dream, and meaning can only be derived by analyzing the metaphorical connections between them without the benefit of any fixed external reference.

Bring out the romantic features of kubla khan.

Kubla khan is a concentration of romantic features. Content and style together evoke an atmosphere of wonder and romance enchantment.

Supernaturalism. A basic feature of Coleridge’s poetic art is his ability to render supernatural phenomena with artistry. This is also a characteristic of romantic poetry . while kubla khan is not a poem collectively give it an atmosphere of other worldly enchantment. The “caverns measureless to man a “sunless sea”, a

“woman wailing for her demon lover”, ”the mighty fountain forced momently from

that romantic chasm”- these are all touches, which create an atmosphere of mystery and arouse awe. But the description is so precise and vivid that no sense of unreality is created.

Sensuous Description.Romantic poetry is also characterized by sensuousness. like Keats, Coleridge exhibits a keen observation. There are sensuous phrases and pictures in Kubla Khan. The bright garden, the incense-bearing trees with sweet blossoms, the sunny sports of greenery, rocks vaulting like rebounding hail, the sunless caverns these are highly sensuous images. Equally sensuous is the vision of the Abyssinian maid playing on a dulcimer and singing a sweet song.

Distant setting. References to distant lands and far-off places emphasis the romantic character of kubla khan. Xanadu, Alph, Mount Abora belong to the geography of romance and contribute to the romantic atmosphere. There are highly suggestive lines in the poem and they too are romantic in character. For instance, the picture of a woman wailing for her demon-lover under a waning moon is very suggestive- “a savage place… holy and enchanted” Coleridge calls it. Equally suggestive are these lines

And mid this tumult kubla heard from far

Ancestral voices prophesying war.

Poetic creation. The picture of the divinely has inspired poet in the closing lines is typically romantic. No writer imbued with the classical spirit have written these liens where the poet is presented as a divinely inspired creator. The poet achieves an awesome personality of whom the ordinary persons must

“Beware”.

Dream-like quality. Kubla khan, is a work of pure fancy, the result of sheer imagination. The dream-like atmosphere of the pome is purely romantic.

Romanticism In Kubla Khan: C.U. English Honours Notes

Coleridge excels his contemporaries in the psychological treatment of the Middle

Ages, where, a strange beauty is there to be won by strong imagination out of things unlikely or remote. The exquisite, distant setting of Kubla Khan is laid in harmony with this aspect of Romanticism, that is, “strangeness added to beauty”. The first stanza gives a sensuous, typical pictorial presentation of an earthly paradise, which does not have any historical significance. It is the landscape of Xandu, which Kubla Khan has selected for building his pleasuredome, on the bank of the river Alph. Thus a medieval, autocratic Chinese monarch forms the subject of the poem. The names--- Xandu, Alph etc.

— unfamiliar and wrought with the spirit of mystery, lend to the poem an enchantment of their own. The exotic plot of land is one of teeming nature — garden, hills, serpentine rivulets, forests and spots of vegetation —all these embracing the centrally l ocated “miracle of rare device”, that is, Kubla’s palace.

Down the slopes of the green hills runs a “deep romantic chasm”. A mysterious atmosphere hangs over the place as a woman is heard lamenting for her deserted demon-lover. The story derives its origin from the Gothic tales. The nocturnal beauty of the paradisal landscape is maligned by the “waning” lunar crescent. This is a morbid aspect of romanticism. The second part of the poem also exhibits his inclination for medievalism as here the poet transports us to the far-off land of Abyssinia.

It is the perception of “strangeness added to beauty” that makes for the

Romantics’ interest in the supernatural—in things veiled under mystery. The essence of Coleridge’s romanticism lies in his artistic rendering of the supernatural phenomena. The “woman wailing for her demon lover” and “the ancestral voices prophesying war” are obviously supernatural occurrences. The process of the genesis of the river —the bursting of the fountain volleying up huge fragments and its subterranean terminus evokes a sense of wonder and awe. Towards the end of the poem the poet is presented as a supernatural being feeding on honey-dew and milk of paradise.

Kubla Khan is remarkable for its sensuousness which is a great romantic feature. It abounds in sensuous and picturesque description of the vast stretch of land overgrown with the beauties of nature:

“And there were gardens bright with sinuous rills,

Where blossomed many an incense-bearing tree:

And here were forests ancients as the hills,

Enfolding sunny spots of greenery.”

The shadow of the dome floating midway on the waves is also sensuous. The sensuousness is further reinforced with the description of the Abyssinian maid playing on her stringed instrument and singing of Mount Abora. The images employed in the poem are sensuous. The dome is an agreed emblem of fulfilment and satisfaction. Its spherical shape is likened to a woman’s breast, both being circular and complete. Moreover, the word “pleasure” is the recurrent qualifier of dome--“a stately pleasure dome” in the line 2, “the dome of pleasure” in the line 31, “a sunny pleasure-dome” in the line 36. The other sensuous images are “thresher’s flail”, “rebounding hail”, “caves of ice”, “sunny dome” etc.

Kubla Khan is essentially a dream-poem recounting in a poetic form what the poet saw in a vision. It has all the marks of a dream —vividness, free association and inconsequence. The dreamlike texture of Coleridge’s poem gives it a kind of twilight vagueness intensifying its mystery. This dream-quality contributes greatly to making the poem romantic.

To conclude, it has been rightly said that Coleridge’s poetry is “the most finished, supreme embodiment of all that is purest and ethereal in the romantic spirit”.