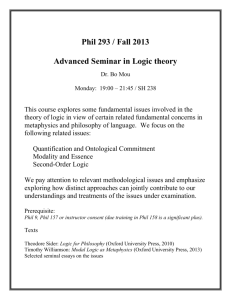

Case Study 3 Philip Anderson

advertisement

Case Study Philip Anderson It was three days to month end. Philip Anderson, the Phoenix branch manager of Stuart & Co., the largest brokerage firm in town, was dreading the monthly teleconference meeting with his bosses in New York. Once again his team had failed to deliver on some of the specific product sales targets set for them in the company’s sales budget. Specifically, the ratio of in-house to outside product sales of items such as mutual funds and insurance product offerings had not improved from the prior month; his team had not been successful in pushing equity issues syndicated or underwritten by the parent firm to the levels set by his boss a few months earlier; and his team had not increased the overall balance of margin accounts. On the positive side, the number of margin accounts had increased, new clients had been signed up, and overall branch revenues had increased. But Phil questioned how long he would be able to justify not meeting some of the specific targets the firm had given his branch. Phil began his sales career right after college. His first job was with a cereal producer, as an inside salesman. He switched to the brokerage business after just two years, lured by the potential for higher income and the opportunity to have direct contact with retail clients. Phil was an outgoing individual who had a talent for financial matters, and he looked forward to a job that would allow him to interact with clients directly. Just five months ago, Phil had celebrated his 30th year in the brokerage industry and his 21st year with Stuart & Co. Although he truly enjoyed being a manager and working with his team, some of the other demands of the job were beginning to wear on him. Things had not turned out as he had expected. Phil thought of himself as a hard-working and loyal employee, a good manager, and an ethical businessman. The “compromises” that his career seemed to demand were beginning to trouble him. He did not consider himself a saint, and he knew that his job required balancing conflicting goals, but he wondered how far he could bend without breaking. Phil started his brokerage career with one of the largest firms in the industry. He moved to Stuart & Co., then a boutique firm, in the hope of breaking free from the high-pressure sales-oriented attitude prevalent in the industry. He thought that the perception that the large firms tried to perpetuate – that their advisors are experts at providing unbiased financial advice – is for the most part wrong. Phil learned firsthand that brokers are paid, first and foremost, to sell products and services. Meeting the financial needs of their clients was not paramount. Stuart & Co. seemed to be different. It was a firm that emphasized the development of long-term client relationships based upon rendering expert independent financial advice. Its investment advisors were to be trusted counselors to clients on all financial matters. But Phil was also lured by Stuart’s compensation package, which included a relatively large fixed salary and a bonus based upon overall branch revenues, growth in the number of ties or relationships (financial, insurance, investment) developed with each customer, and the number of business referrals to other branches. However, things had changed since he had joined the firm. As the investment and analysis units expanded, the demand on the branch managers to push specific products began to be incorporated into their annual sales budgets. Phil felt that those changes had compromised his ability to deliver investment options suited to his clients’ financial situations. They risked the many long-term relationships with clients that he had worked hard to develop and created ethical dilemmas for him and his staff. Phil felt that pursuing some of the new budget goals could result in future financial losses for some of his clients. However, Phil had worked in the brokerage industry and at Stuart & Co. long enough to know that it was dangerous to openly express those concerns to his boss. Additionally, Phil was troubled with the recent scandals in the industry. It was mostly low-level employees like him who were the object of criminal prosecution, not the top executives. As Phil saw it, his job was to develop and nurture profitable relationships with as many clients as possible, and the specific products and services sold to clients should be dictated by the needs of those clients. Consequently, he could never bring himself to pushing his team to adhere to the firm directives, and this approach had negatively impacted his total compensation in the last few years. Invariably, his annual bonus lagged behind those of other managers at Stuart & Co., even though his branch was one of the largest in the firm in terms of clients, sales volume, and net profits. Phil felt his current situation was unfair. He also was beginning to worry that his failure to meet specific product sales targets was eroding whatever measure of job safety his overall results had given him. To compound the situation, Stuart & Co. had recently been bought by one of the largest brokerage firms in the country, and it seemed that the new hierarchy did not take well to independent-minded managers like Phil who did not aggressively pursue the objectives set out by corporate. Phil was getting tired of the game but could not see how he could avoid playing it. He was almost 54 years old and was the sole provider for his family. His wife had retired a year before from her teaching job to take care of their three teenage sons. They had just recently bought a 4,000-square-foot home in an exclusive neighborhood of Scottsdale. And last fall, Phil had fulfilled a college dream by buying for himself a brand-new red Corvette. Phil feared that if he allowed his team of advisors to continue focusing on meeting their clients’ needs with little regard for corporate targets, more than his discretionary compensation would be at risk. Phil had many questions and doubts, and few answers. Was he right in allowing his clients’ financial goals to take precedence over his own family’s financial security? Was he being unreasonable, naive, or impractical? Was there somewhere a proper balance? Was he being too ethical at a time when his family’s future should be his primary concern? Or perhaps it was time for him to find another employer that shared Phil’s philosophy, if one existed in the brokerage industry? But could he find another good job at his age? Or should he even bother? After all, he had done his part. Maybe it should be the job of some younger managers to champion the cause of service to clients and continue the battle. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- This case illustrates a common control system dysfunctional side-effect—incentives-caused conflicts of interest faced by brokers in the retail brokerage industry. Sometimes brokers are torn between serving their clients’ and their firms’ best interests. There are two sets of questions for this case. Please be sure to review both. Question Set #1: 1. Does Philip have an ethical obligation to serve his clients’ interests to the best of his ability, even at some cost to his firm and, presumably, himself? 2. What should financial service firms’ stance be in situations like this? Do they want brokers to maximize longterm profits even if that does not serve their client base optimally? Are brokers more like professional advisors or salespeople? This next set is based on the scenario below. Review the scenario and answer the questions below. SCENARIO: Assume that one of Philip’s clients is a married man, aged 36 with two young children, who wishes to reallocate a significant portion of his retirement funds that are currently invested in certificates of deposit. Philip recommends a growth investment, and he identifies the three representative possibilities shown in Table A Question Set #2: 1. Which investment alternative: a. provides the highest returns to the client? b. provides the highest profits to Stuart & Co.? 2. If your answer to (b) is not the same as your answer to (a) and Philip recommends the highest profit choice, is he acting unethically? Why or why not? 3. Which alternative should the top management of Stuart & Co. want Philip to recommend to his client? Is the company’s control system designed to ensure that choice?