afghanistan-nca-strategy-2016-2020

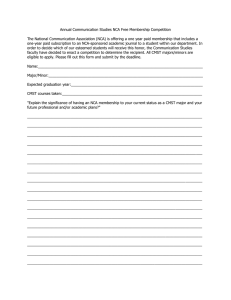

advertisement