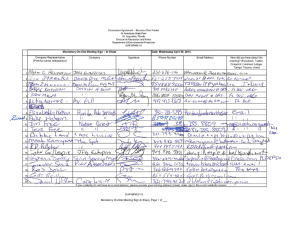

12. Chapter 7 - On Site Food Service

advertisement