Robinson-et-al.-2014-Growing-up-Queer

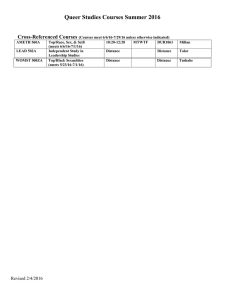

advertisement