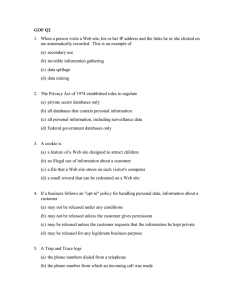

end of trust interior pages lores

advertisement