Sustainable Livelihood Approach

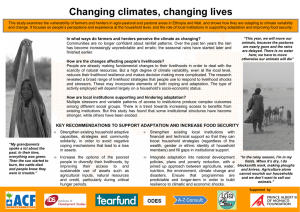

advertisement