TOPIC RATIFICATION OF MINORS AGREEMENT I

advertisement

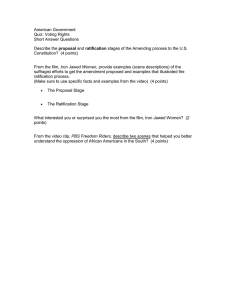

NATIONAL LAW INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY 2015 LAW OF CONTRACTS-I PROJECT TOPIC~ RATIFICATION OF MINOR’S AGREEMENT IN INDIA AND ENGLAND. Submitted By~ MUDIT NIGAM B.A.LL.B(Hons.)-46 Submitted To~ MRS. PADMA SINGH ASSISTANT PROFESSOR 2nd TRIMESTER. 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I take this opportunity to express my profound gratitude and deep regards to my guide PROF. PADMA SINGH for his exemplar guidance, monitoring and constant encouragement throughout the course of this thesis. The help and guidance given by him time to time shall carry me a long way in the journey of life on which I am about to embark. I am obliged to staff members of NLIU for the valuable information provided by them in their respective field. I am grateful for their cooperation during the period of my assignment. Lastly I thank almighty , my parents and friends for their constant encouragement without which this assignment would not be possible MUDIT NIGAM 2015-B.A.LL.B.-46 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS TOPIC PAGE NO INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………Page 4-5 OBJECTIVES…………………………………………………………..Page 12 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES……………………………………………..Page 6 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY………………………………………Page 6 SOURCES OF DATA………………………………………………….Page 6 FRAMING OF HYPOTHESIS………………………………………..Page 6 DESCRIPTION…………………………………………………….....Page 7-18 PART A : INDIAN LAWS PART B : ENGLISH LAWS PART C: DIFFERENCES CONCLUSION………………………………………………..……… Page 19 BIBLIOGRAPHY ……………………………………………………...Page 20 3 INTRODUCTION The generally accepted principal whereby acts which have no effect on the principal because they have been carried out by an agent holding itself out to have authority but actually without its authority or exceeding its authority may be authorized by the principal, at a later stage. Such subsequent authorization is known as ‘Ratification’. Like the original authorization, ratification is not subject to any requirement as to form. As it is unilateral manifestation of intent, it may be either express or implied from words or conduct and, though normally communicated to the agent, to the third party, or to both, it need not to be communicated to anyone, provided that is manifested in some way and can therefore be ascertained by probative material. Contract ratification is necessary when a contract is voidable but the parties determine that they would prefer to execute and perform the contract anyway. For example, if a 16-year-old signed a contract to purchase a car, that contract would be voidable, as contacts can only be signed by individuals 18 years or older. On reaching the age of majority, the person who signed when underage can honor the purchase contract through ratification. As a smallbusiness owner, you may be required at times to ratify contracts signed by individuals who were not authorized to provide a signature. Void contracts cannot be ratified because they are not capable of being legally executed. Examples of void contracts include contracts based on illegal subject matter, contracts for the performance of impossible events, and contracts restraining a person's choice of who to marry. Contracts that are otherwise voidable, but not void, can be faithfully performed through the process of ratification. Examples of voidable contracts include contracts where a party is incapacitated at the time of signing due to drugs or alcohol, and contracts made under conditions of duress. If you wish to ratify a voidable contract, you should draft a letter to the other party. In your letter state why you desire to ratify the contract and why you believe the contract is capable of being upheld. Ask that the other party contact you, and ask if they are willing to sign a ratification agreement. Ratification agreement must state that the parties desire to ratify a contract, and a copy of the contract should be attached to the ratification agreement. The ratification agreement should state the date of ratification. You can also include additional 4 clauses, such as how notice is to be provided under the agreement and the state law governing the agreement. The ratification agreement must be signed by both parties. in English contract law, a minor is any individual under the age of 18 years old. Historically, the age had been 21, until the Family Law Reform Act 1969. As a general rule, a minor is not bound by contracts he makes, though the adult party whom he contracts with is. Once a minor reaches the age of majority however, he can elect to ratify a contract made as a minor in full capacity. This rule is subject to several types of contracts which a minor will be bound by, and his right to repudiate such contracts. 5 AIMS AND OBJECTIVE~ The aim of the researcher is to do a descriptive and analytical study of the contractual validity of agreements in subject to ratification by others. This is in special context to minor’s agreement. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY~ As whole research work for this work is confined to the library, books and internet and no field work has been done hence researcher in his research work, the researcher has opted the doctrinal methodology of research. Researcher has also followed the uniform mode of citation throughout the project work. SOURCES OF DATA~ The following Sources of data have been used in this project1. Books 2. Internet 3. Journals FRAMING OF HYPOTHESIS Before starting the project work, the researcher has presumed the following hypothesis: “Ratification means the subsequent adoption and acceptance of an actor agreement. A minor's agreement being a nullity and void ab-initio has no existence in the eye of law. It cannot be ratified by the minor on attaining the age of majority, for, an agreement void abinitio cannot be made valid by subsequent ratification” 6 “INDIAN LAW” CONRACTUAL VALIDITY OF AGREEMENT SUBJECT TO RATIFICATION Ratification is in law equivalent to previous authority it may be expressed or it may be affected impliedly by conduct1. Section 196 and 197 of the act show that an act done by person who is not authorized to do it, but who purports to act as an agent for another person, can retrospectively ratified by such other person. From this it follows logically, that such an act on the part of the person purporting to act as agent is not void but voidable. If it is not ratified it becomes void but if it is ratified it will be validated. 2 It is doubtful that whether the term “ratification” may properly be applied to the conduct of a person, who choose to treat as genuine a promissory note on which his signature has been forged3.It is rather on the principal of estoppel that such a person may, under such circumstances render himself liable. Ratification in order to be effective can only be by an authority that is in existence on the day of transaction was entered into and it should also be competent to ratify. There is ample material on record in the present case that the company had ratified the act of the person who had signed on behalf of the company even his act of signing on behalf of the company was without authority. The doctrine of ratification comes into play when a person has done an act on behalf of another without his knowledge or consent. The doctrine gives the person on whose behalf the act is done an option either to adopt the act by ratification or to disown it. So, it can be derived that ratifications are either empress or implied. The former are made in express and direct terms of assent; the latter are such as the law presumes from the acts of the principal; as, if Soham buy goods for Rahul, and the latter, knowing the fact, receive them and apply 1 Jai Narain Lal Tandon v. Bechoo Lal, A.I.R. 1938 All. 369 Bhawani Shankar v. Gordhandas Jamunadas, A.I.R 1943 P.C. 3 Book v. Hook, L.R. 5 Ex. 2 7 them to his own use. By ratifying a contract a man adopts the agency; altogether, as well what is detrimental as that which is for his benefit. Therefore ratification is a kind of affirmation of unauthorised acts. It is thus explained in section 196 of Indian Contract Act 1872 and in other section. 196. Right of a person as to acts done for him without his authority- Effects of ratification.Where acts are done by one person on behalf of another, but without his knowledge or Authority, he may elect to ratify or to ratify or to disown such acts. If he ratifies them, the same effects will follow as if they had been performed by his authority.4 197. Ratification may be expressed or implied.Ratification may be expressed or may be implied in the conduct of the person on whose belief the acts are done. 198. Knowledge requisite for valid ratification. Therefore as a general rule of this subject, the principal has the right to elect whether he will adopt the unauthorized act or not. But once doing a ratified act, upon a full knowledge of all the material circumstances, the ratification cannot be revoked or recalled, and the principal becomes bound as if he had originally authorized the act. So, the ratification of a lawful contract has a retrospective effect on the subject, and binds the principal from its date, and not only from the time of the ratification, but for the ratification is equivalent to an original authority, according to the maxim, that Omnis ratihabitio mandate aeguiparatur. Therefore such ratification in general meanings relieve the agent from all responsibility on the contract, when we would otherwise have been liable for such kind of act. So an infant is not liable on his contracts; but if, after coming of age, he ratifies the contract by an actual or express declaration, he will be bound to perform it, as if it had been made after he attained full age. Hence it can be conferred that the ratification must be voluntary, deliberate, and intelligent, and the party must know that without it, he would not be bound to fulfill the obligation. But a confirmation or ratification of a contract, may be implied from acts of the infant after he becomes of age; as by enjoying or claiming a benefit under a contract be might have wholly rescinded and an infant partner will be liable for the contracts of the firm, or at 4 Williams v. North China insurance Co. (1876) 1 CPD 757 8 least such as were known to him, if he, after becoming of age, confirm the contract of partnership by transacting business of the firm, receiving profits, and the like. We can take example of ratification of Treaties. VALIDITY OF CONSENT The English common law relating to the above topic report from the two Latin Maxims Qui Per Alium Facit Per seiprom facere Videtur and Qui Facit per alium facit perse thereby meaning “ He who does not act through another is deemed in law to do it himself” and ‘he who acts by another acts by himself”. The law of agency is based upon the consent of one party that the other party the agent shall act on his behalf and the other party consents to do so. According to CHITTY5 “At common law the word Agency represents a body of general rules under which one person the agent has the power to change the legal relation of another, the principal.” According to ANSON “ Although at common law as a general rule A cannot by contract with B to confer rights or impose liabilities upon a third party, yet A may or act on the behalf of B with B’S authority for the purpose of bringing B in a legal relations with a third party6. So principal is bound by the act done by an agent or the contracts made by made by him on behalf of the principal in the same manner, as if the acts had been done or the contracts had been entered into by principal himself, in person7. Therefore when a contract is entered into through the medium of an agent the principal becomes liable towards the third party whether he has given his consent before or not, it does not matter even when such contracts are voidable in nature. Ordinarily, as the agent is only a connecting link, he is not liable personally towards the third party 8 5 H.G.Beale, Chitty on Contracts ( special contract Act), (Sweet and Maxwell,30th Edition,2008) J Beastson, Anson’s Law of Contract (Oxford University Press,28th ed., 2008) 7 Sec.226 8 Sec 230 6 9 The power to ratify remains with the principal itself so consent given or not to agent it hardly matters because obligation part comes to principal.9 Conditions of a valid ratification Act must be done on behalf of another.1. The first essential to the doctrine of ratification, with its necessary consequence of relating back, is that the agent shall not be acting of himself, but shall be intending to bind a named or ascertainable principal. 10 The agent must have done the act on the behalf of the supposed principal.11And the motive with which the act done is immaterial. 12 2. Person ratifying must have been in existence at the time of act.- it has been laid down that ratification , in order to be effective, can only be by an authority that is in existence on the date the transaction was entered into and it should also be competent to ratify13. 3. The thing must exist- In order to recognize or ratify something it is necessary that thing must exist14, that is the contract, or some rights or obligations arising under it, must be subsisting on the date of Ratification. 4. Ratification must be with full knowledge of all facts. In order to establish case of ratification it is essential that the party ratifying should be conscious. 5. Ratifier must have been competent to authorize the act. The act to be ratified must be one which the person ratifying had himself power to do and the ratification must take place at a time, when and under circumstances under which, the ratifying party might himself have lawfully done the act which he ratifies.15 9 Justice A. RAMAN, Law of Contract and Specific Relief p.no.253(2nd editon,1984) Imperial Bank of Canada v. Mary Victoria Begley, A.IR.1936 P.C 193 11 Marsh V. Joseph [1897] 1 ch. 214; Surendra Nath v. Kedar Nath, A.I.R 1936 CAL. 8 12 Subbaraya Chetty v. Nagappa Chetty, A.I.R 1927 mad. 805: 103 I.C. 150 13 Mohammad Tajuddin v. Gulam Mohd., A.I.R. 1960 A.P 340 at p. 342 14 Suckchand v. Girdhari Das, A.I.R 1926 Cal. 1215 at P. 1217: 4 C.L.J 127: 97 I.C. 1016 15 Bird v. Brown (1850) 4 EX. 786 : 80 R.R 775 10 10 In the words of Sir B. Peacock: “ A ratification is in law treated as equivalent to a previous authority, and it follows that, as a general rule, a person or body of persons, not competent to authorize an act, cannot give validity by ratifying it”16 In Suraj Narain v. N.W.F. Province17, it was held that where the responsibility for the passing of a particular kind of order is by statute vested in specific authority. 6. Ratification to be exercised within reasonable time. An option of ratification must be exercised within a reasonable time of the act purporated to be ratified 18, “ ratification” in every case within a reasonable time. 7. Communication of ratification to other side. There can be no ratification of contract unless it is communicated to the other side or subsequent action shows an approbation of the contract.19 8. Act to be ratified must not be void or illegal. An act which is void or illegal cannot be validated by any amount of ratifications.20 9. There must be relationship of principal and agent. - Another condition to be satisfied is that there must be a relationship of principal and agent.21 16 Irvine v. Union Bank Of Australia, I.L.R C Cal. 280 A.I.R. 1942 F.C. 3. 18 Madura Municipality v. Alagiri Swami Naidu, A.I.R. 1939 Mad. 957 19 Ganpat Rao v. Iswar Singh, A.I.R 1938 Nag. 482 20 Kishor Das v. Raman Lal, A.I.R. 1943 Bom. 362 17 21 Kalyani Achi v. K.N.S.R.M.A.R Ramanathan Chetty, 28 I.C. 135 AT PP. 137-38 11 VALIDITY OF MINOR’S CONTRACT In Minor’s case~ The contract act simply states that a person who is of the age of majority is competent to contract, and thus, a minor’s is not competent to contract. In Mohori Bibee v. Dhurmodas Ghose 22 Privy Council made it clear that that contract or agreement done with Minor is void. No Ratification of a minor’s agreement~ An agreement entered into by a minor is void ab initio. A minor can’t ratify an agreement on attaining the age of majority validate the same.23 One of the reason for the rule that a minor cannot ratify an agreement after attaining majority is that when the agreement was entered into during the minority there was no ‘proper consideration’ and the ‘bad consideration’ is not enough for validating that agreement by its ratification. This will be clear from the observation of SULAIMAN, C.J. of the Allahabad High Court:24 “Under section 11 a minor is not competent to contract he is disqualified from contracting. He can, therefore, neither make valid proposal nor make a valid acceptance as defined in section-2, clause (a) and (b). He cannot, therefore, for the purposes of this Act be strictly called a promisor within the meaning of clause (c). Nor can, therefore, anything done by the promise be strictly called a consideration at the desire of a promisor as contemplated by clause (d). It may, therefore, be urged that an argument by a minor cannot be strictly as being for “consideration”..... If the part of the benefit was received by a person during his minority and the other part after attaining the age of majority, a promise by him after attaining majority to pay an amount in respect of both the benefits is enforceable, as that constitutes a valid consideration for the 22 (1903) 30 IA 114 (PC). Indran Ramaswamy v. Ananthappa, 16 MLJ 422 24 Suraj Narain v. Sukhu Aheer, AIR 1928 All 440. 23 12 promise25.A minor can’t even enter into a contract through guardian or any other agent because it is void contract and the same is not capable of ratification by a minor, on his attaining majority. According to Privy Council26 stated that “A ratification in law is treated as equivalent to a previous authority, and it follows that as a general rule, a person or body of persons, not competent to authorize an act can’t give validity after ratifying it. State liability for the act officers~ The matter has been discussed under sec.65. In Chatturbhuj Vithaldas Jasari v. Moreshwar Parashram27, the contention was raised that the contracts having not been expressed to be made by the President as required by Article 299 of the Indian constitution were void, but it was ruled that the contracts in question are not void simply because the state officers who made such contracts could be sued upon them, and they could be by the Government.28 Ratification after principal’s death:It is common practice that if an agent functioning under a written authority of the principal holds himself out as such agent after the death of the principal and if person competent to ratify his action after the death of the principal ratify the same in manner known to law, then the agent should be deemed to have acted within the limits of authority and that he validly holds himself out as agent of the subsequent proprietors.29 25 Kundan Bidi v. Sree Narayan, (1906-07) 11 CWN 135. Irvine v. Union Bank Of Australia, ILR (1877) 3 Cal 283 (PC) 27 A.I.R 1954 S.C. 236. 28 Sewakissendas Bhather v. Dominion of India, A.I.R. 1957 Cal. 617. 29 Management of Sri Sivasakthi Bus Service v. K.P. Gopal, A.I.R. 1971 Mad. 434 26 13 EFFECTS OF RATIFICATION It is established that rule that an act done for another by a person not assuming to act for himself, but for such other person, though without any precedent authority whatever, becomes the act of the principal if subsequently ratified by him, within a reasonable time. In the case of a continuing obligation, such as the engagement of a servant or the continuance of tenancy, an absence of repudiation or acceptance of service or rent with full knowledge of the facts, implied an undertaking to adhere to the obligation and operates as ratification or renewal of the old contract by the party accepting the service or rent.30 So the ratification relates back to the original making of contract and confirms it from that time. It places all the parties in exactly the same position31 as they would have occupied in the case of a precedent agency by formal constitution. So ratification will support an action previously brought upon the contract in the name of the principal, though without his knowledge. The same is equally true of arbitration.32 30 Huddain Ali Murja v. Mohd. Azim Khan, 31 I.C. 728 Supra note 8. 32 Saturjit v. Dulhin, I.L.R. 124 Cal. 469 31 14 ENGLISH LAW MINORS AND THEIE CAPACITY TO CONTRACT IN ENGLAND Those individuals who are under the age of 18 are recognised as minors, this is outlined under the Family Reform Act 1969. Minors have capacity limitations; there are different types of contracts where there may be liability of minors. The Sale of Goods Act (1979) defines liability of minors when buying necessaries. Necessaries are the basic goods needed for living, The Sale of Goods Acts states, ‘goods suitable to the condition in life of the minor’. Therefore, minors are liable under a contract for buying necessaries. Necessaries extend beyond the essentials for living, they can also be items which are needed for a young person and for their lifestyle. The minor is not liable for goods or services that have not been delivered to them. Valuable utility items may be considered necessaries but items of luxury are not considered as necessaries. Therefore, a minor would still be liable to pay for such utility items. An example of this was in the case of Chapple v Cooper (1844), where a service was considered necessaries. However, in the case of Nash v Inman (1908), it was decided that waistcoats supplied to a student could have been considered as necessaries, but in this case they were not necessaries because the student’s father had already provided the student with many waistcoats. When something is considered necessaries and the minor liable to pay a reasonable price, this would depend on the income of the minor and whether the goods and services are actually necessaries and are needed by the minor. It would also depend on the supply, even if the minor needed something and can afford it, the good or service would not be considered necessaries if the minor already has a supply of it. Contracts that are considered for the benefit of the minor are that of service, education, training, apprenticeship and employment. However, the courts will reject a contract if it is considered not in the benefit of a minor. For example, in the case of De Francesco v Barnum (1889), a minor aged 14 years old, had an agreement to train as a dancer on stage, however, the contract had conditions which were considered not beneficial to the minor and therefore, the minor was not bound by the contact. A case where a contract had been enforced is the case of Doyle v White City Stadium (1935), this is where there was an agreement to train a boxer. There was no money paid, but the contract was enforceable because it was considered that the contract was beneficial because 15 of the training. In another case where the contract was enforceable was in Clements v London & NW Rail Co (1894) where certain benefits were removed from the contract, but the contract was considered to be beneficial. VOIDABLE CONTRACTS WITH MINORS There are four types of contract, commonly referred to collectively as ‘voidable contracts’, which bind both the parties unless the minor repudiates them. The minor can repudiate before he attains majority or within a reasonable time thereafter. The contracts are : Contracts relating to an interest in land (a minor can no longer hold alegal estate in land- Law of Property Act-1925, s 1(6) ) Marriage settlements e.g. In Edwards v Carter.(1893) A minor tried to repudiate on an agreement to pay £1500 to trustee's under a marriage settlement some four years after obtaining majority. Held whilst minors can repudiate an agreement they can be sued for liabilities which have already occurred, thus the minor was not allowed to repudiate the agreement as he had entered adulthood. Point of law being that minors can repudiate a contract after the age of majority after a reasonable time, however what is reasonable depends on the facts of the case. Justice Watson wrote : “The law gave this minor the privilege of repudiating the obligations which he had undertaken during his minority within a reasonable time after he came of age. It laid no obligation upon him - it merely conferred upon him a privilege of which he might or might not avail himself, as he chose. If he chooses to be inactive, his opportunity passes away. If he chooses to be active, the law comes to his assistance." The purchase of or subscription of shares e.g. Steinberg v. Scala (leeds) Ltd. (1923) A minor brought shares in Scala, the shares were not fully paid up, the issuing company could demand the rest of the payment latter. They didn't but Ms S paid a further £250. She latter rejected the contract and wanted her £250 back. Her claim failed, held, termination meant free from future obligation but not instilled to £250 because she had not been a total failure of consideration as she had received the shares in return for her money 16 Partnerships e.g. Goode v Harrison (1821) In Goode v. Harrison, Bayley, J., in this case, said: "It is clear that an infant may be in partnership. It is true that he is not liable for contracts entered into doling his infancy; but still, he may be a partner. If he is in point of fact a partner during his infancy, he may, when he comes of age, elect if he will continue that partnership or not. If he continues the partnership, he will then be liable as a partner; if he dissolves the partnership, and if, when of age, he takes the proper means to let the world know that the partnership is dissolved, then he will cease to be a partner. But the foundation of my opinion is the negligence of service generally binding.1 But enlistments in the navy, though made without the consent of the parent or guardian, are binding, and the infant cannot avoid them and it is the same as to the army. RATIFICATION Ratification with minor does not fall within one of the situations (where it is binging),it is not binding upon the minor. It is binding upon the other party, but the minor is unlikely to succeed in an action for specific performance, unless he has already performed his side of the agreement, because if the lack of mutuality. Flight v. Bolland (1828) In this case A., an infant, entered into a contract with B. B. refused to perform. A. brought his bill against B. for specific performance of the contract. The plaintiff being an infant was not amenable to an order of a court of chancery. Had therefore the defendant been the plaintiff he could not have had specific performance of A.'s promises. The court dismissed the plaintiff's bill, saying, "It is not doubtful that it is a general principle of courts of equity to interpose only where the remedy is mutual." However, even if the contract is not within one of the special cases, it may become binding upon a minor if he ratifies it, expressly or impliedly, upon attaining age of his majority. Ratification could occur at common law ( Willaims v Moor (1843) )and the repeal of s 2 of the Infants Relief Act 1874 by the Minors Contracts Act 1987 means that it is , again, generally available. 17 Before Ratification, the minor will not be bound. Again it would seem that recovery by the minor of any property transferred under the “contract” is possible only to the extent that an adult would able to do so, e.g.. if there has been a total failure of consideration. Again it has been argued that the restitution should be available simply on the basis of incapacity DIFFERENCES IN INDIAN AND ENGLISH LAWS The English Law is the principal source of Indian Law. But the Indian Law differs from English Law on the subject of minor’s contracts on the following points: 1.In India the minor’s contract is altogether void but in England it is sometimes void and sometimes voidable. In England the loan of money to a minor is void. 2.In India, a minor can ratify a fresh consideration of a contract entered into during minority where as in England he cannot do so. 3.In India a minor on attaining majority can neither sue nor be sued on contracts entered into by him during minority but in England he can sue on the contract for damages. 4.In India a minor’s property is liable for the necessaries and not his personal self acquired property but in England the minor is personallyliable. 5.In India there can be no specific performance by or against the minor unless it is a contract entered into by a guardian on behalf of the minor sand the minor’s benefit. In England there can be no specific performance for want of mutuality in the contract. 18 CONCLUSION From this project the researcher came to the conclusion that contractual validity agreement in subject to ratification clearly says that where acts are done by one person on the behalf of another, but without his knowledge or authority, he may elect to ratify or to disown such acts. If he ratifies them, the same effects will follow as if they had been performed by his authority. Agreements which are subject to ratification are voidable in nature. If it is ratifies by the principal then it becomes legally valid in the court of law. If it is not ratified then the contract will lose its validity. Similarly if the principal has not consented and not given his consent to his agent to enter into agreement still he owes a duty towards third party because principal is bound by the acts done by an agent or the contracts made by him on behalf of the principal in the same manner, as if the acts had been done or the contracts had been entered into by the principal himself, in person. The principal is vicarious liable for the frauds or torts committed by the agent, while acting in the course of the business for the principal. Similarly in the agreements which are related to minors are void ab initio because they are not competent to contract and the contract is void. Law acts as the guardian of minors and protects their rights, because their mental faculties are not mature- they don't possess the capacity to judge what is good and what is bad for them. Accordingly, where a minor is charged with obligations and the other contracting party seeks to enforce those obligations against minor, the agreement is deemed as void ab-initio. In the leading case of Mohori Bibi vs Dharmo Das Ghosh, a minor executed a mortgage for Rs. 20,000 and received Rs. 8,000 from the mortgagee. The mortgagee filed a suit for the recovery of his mortgage money and for sale of the property in case of default. The Privy Council held that an agreement by a minor was absolutely void as against him and therefore the mortgagee could not recover the mortgage money nor could he have the minor's property sold under his mortgage. 19 BIBLIOGRAPHY BOOKS 1. H. G. Beale, Chitty on Contracts (30th ed. 2008) 2. R.G. Padia. Pollock & Mulla’s Indian Contract and Specific Relief Act (13th ed. 2007) 3. P.S Atiyah, Introduction to the Law of Contract (Stephen A. Smith ed., 2007) 4. J Beastson, Anson’s Law of Contract (28th ed. 2008) 5. MLJ Law OF CONTRACT AND SPECIFIC RELIEF 2nd ed. 2009 justice araman vol. 1 WEBSITES 1. “Ratification” available at: http://www.legalservicesindia.com/article/article/contract-ratification-434-1.html 2. “Indian Law Applicable to Agreement subject to ratification – Consequences” available at: www.unidroit.org/english/principles/contracts/ 3. “ratification of contract” available at: http:// www.getfreelegalforms.com/ratification.html 20