Biocomputing: DNA & RNA Structure

advertisement

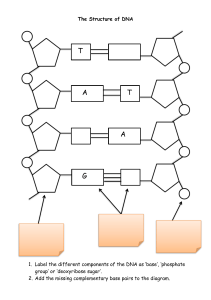

Introduction to Biocomputing: Structure (DNA & RNA) 1 •genome: biological information in an organism •DNA: deoxyribonucleic acid, carries genome of cellular lifeforms •RNA: ribonucleic acid, carries genome of some viruses, carries messages within the cell •bases: the four bases found in DNA are adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), and Thymine (T); in a “double helix” of DNA, bonds are always A--T or C--G; thus a single strand of DNA carries the information about the strand it would bond to So DNA can be thought of as a “base 4” storage medium, a “linear tape” containing information in a 4-character alphabet 2 DNA—the “double helix” 3 DNA— ”direction” http://www.swbic.org/products/clipart/images/dna2.jpg 4 RNA: Thymine (T) replaced by Uracil (U) and deoxyribose replaced by ribose http://www.swbic.org/products/clipart/images/rna.jpg 5 comparison 6 Translation: DNA rRNA mRNA tRNA protein http://www.swbic.org/products/clipart/images/dogmag.jpg http://www.swbic.org/products/clipart/images/translation.jpg 7 DNA provides the basic “code”. RNA copies this code from the DNA and used this information to form a string of amino acids—i.e., a protein. Proteins “are the machines that make all living things function” 8 •Central Dogma: Before the discovery of retroviruses and prions, this was believed to be the basic mechanism of inheritance in all living things 9 Relative sizes: 10-18: electron 10-15: proton, neutron “nanotechnology”: 10-14: atomic nucleus 10-10: water molecule (angstrom) molecules, atoms 10-9: (nanometer, nm), one DNA “twist” 10-8: wavelength of UV light 10-7: thickness of cell membrane 0.18 or 0.13 mm, Pentium 4 wire width 10-6: diameter of typical bacterium (micron, mm) 10-5: diameter of typical cell 2-10 mm, typical MEMS feature size 10-4: width of human hair 10-3: diameter of sand grain (millimeter, mm) 10-2: diameter of nickel (centimeter, cm) 35 mm--one side of Pentium 4 chip 100: 1 meter 10 Why is biomolecular computing attractive? •Size: --typical bacterium has diameter on ht order of 10-6 m. (1 micron); --one twist of DNA double helix is on the order of 10-9 m. (nanometer scale) •Power requirements should be low •Massive parallel computation is theoretically possible •I/O can be two-dimensional •Instabilities of quantum systems are much less of a problem here 11 What are the disadvantages? •Speed--typical reaction can take hours or days •Error rates--may be unacceptably high; may be introduced by mechanical steps in proocessing data •I/O--we do not yet have efficient mechanisms for doing input/output with these systems •“Herd” property--we can affect a mixture of data items; we cannot in general pick out one specific item; biomolecular computing is inherently parallel •Exponential growth in size of computation--it may be that the speed barrier in traditional computing is replaced by a size barrier in biomolecular computing--we may need too much biological material to solve a reasonable sized problem for the “computation” to be feasible 12 What interesting projects can build on our knowledge of traditional computer engineering? • “structural” designs—DNA computing • “chemical” designs—using proteins as signals 13 Computing using DNA structures: •polynucleotide: a single DNA strand •oligonucleotide: short, single-stranded DNA molecule, usually less than 50 nucleotides in length In DNA computing, specific oligonucleotides are constructed to represent data items. •nucleotide: phosphate group + sugar + one of the 4 bases (A,C,G,T): the phosphate end is labeled 5’, the base end, 3’ Example: in Adelman’s seminal 1994 paper, oligonucleotides of length 20 were built to represent vertices and edges in a given graph: Vertex V1 A Vertex V2 T G T T C C A A G A T Edge V1-V2 14 DNA computing (“structural”, “digital”) Possible operations on DNA: •building up custom oligonucleotide sequences to represent parts of your data •splitting--can be done by heating, e.g. •recombining--can be done by cooling •cutting strand at a particular site •“sticking” two fragments together (at their ends) •sorting by some string property (including length) 15 So-----DNA computing: •uses structure of the DNA •relies on mechanical operations •answers “self-assemble” •basic steps: •encode the problem •make a “solution” of problem fragments •cool the solution so fragments will form longer strands •filter out the answers you want 16 Example: solving graph problems A T T C G A C A A G A T •Encode vertices and edges—use DNA properties to encode graph “structure” •Mix up a solution of your fragments •Cool down, get resulting “paths”, “spanning trees”, etc. 17 “Standard cell architectures, FPGAs” The BioBrick Project Basic idea (after Prof. Tom Knght, MIT): •“gates” are functional units •Ends of gates are standard “join” DNA sequences—reserved for this purpose •So we can build computational chains easily Web page: http://parts.mit.edu/registry/index.php/Main_Page 18 Other applications of DNA computing: •general computing using “sticker” language •study of relationship between traditional architectures and DNA configurations: ---FSMs-linear DNA ---stack machines--branching DNA ---“Turing machines” (general purpose computers)-sheet DNA 19 Other applications of DNA computing (continued): •3-D self-assembled structures: •“walking and rolling DNA”: •structures for nanotube assembly: (recently reported in Science) 20