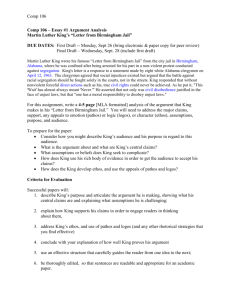

Rhetorical Analysis of King's Letter from Birmingham Jail

advertisement

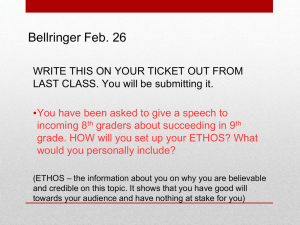

Johnson 1 Abigail Johnson Dr. Trent WRI 234-82C 22 October 2018 The Call to All “In deep disappointment, I have wept over the laxity of the church” (King 379). Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. lamented the church’s indifference during the Civil Rights Movement as he authored “Letter from Birmingham City Jail” whilst a prisoner in Alabama. After a series of non-violent protests for racial equality, Dr. King was arrested in Birmingham. In 1963, the Civil Rights Movement was spreading throughout the United States, but a lack of obligation permeated the church, in turn slowing the progress of equality. As a multi-generational pastor and president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Dr. King responded to the criticism of organized protests from white clergymen in his letter. Within his letter, he effectively used pathos, logos, and ethos to appeal to his audience, all the while engaging syntax and tone appropriate to the social context of the time. A specific rhetorical strategy applied in “Letter from Birmingham City Jail” was ethical appeal establishing Dr. King’s work and authorship. Dr. King established himself as a theologically educated voice. “I also hope that circumstances will soon make it possible for me to meet each of you... as a fellow clergyman and a Christian brother” (King 383). Because Dr. King’s letter was written as a response to clergymen, the emphasis of his association with the church made his criticisms of the church less cruel and more constructive. He responded to their criticism with further credibility: “So I am here, along with several members of my staff, because we were invited here. I am here because I have basic organizational ties here” (King Johnson 2 367). He explained that the demonstration was not a spontaneous decision, but had been a long, deliberate process of determining the most effective way to prove a point without haphazardly impacting other current events like the March election. “These are the practical answers. They establish (if accepted) that he is not in fact an outsider, or at least not a complete outsider” (Fulkerson 127). By providing a thorough explanation for the day of protest, Dr. King further developed his credibility. As the president of the Southern Christian leadership conference and a clergyman, Dr. King effectively provided evidence of the first classical appeal, ethos. Dr. King established the second classical appeal by providing logical evidence in his argument through philosophical, historical, and Biblical references. Most significantly, Dr. King discussed St. Augustine’s theory of laws by describing the dichotomy of law: “The answer is found in the fact that there are two types of laws: there are just and there are unjust laws. I would agree with Saint Augustine that “An unjust law is no law at all”” (King 371). Through logical reasoning, Dr. King urged the audience to decide if segregation laws were even laws at all because of their injustice. “A major source of anxiety concerned the movement’s principled disobedience to law,” but Dr. King confronted the anxiety with direct description of the injustice of the law (Berry 110). The inclusion of historical references, like Hitler, logically encouraged the audience to take a second look at the morality of their actions. “We can never forget that everything Hitler did was “legal”” (King 373). Hitler’s law-abiding practices effectively provided a striking example to which Americans could compare their actions. Finally, Dr. King included Biblical logic for his audience, “Beyond this, I am in Birmingham because injustice is here... and just as the Apostle Paul left his little village of Tarsus and carried the gospel of Jesus Christ to practically every hamlet and city of the Graeco-Roman world, I too am compelled to carry the gospel of freedom beyond my particular hometown” (King 367). Dr. King directly Johnson 3 compared his work towards pursuing Civil Rights to the way that Paul spread the Gospel. His audience admired Paul, the apostle, so that comparison boosted his credibility. “His most significant and searching allusion, one that to a great extent determines not only his persona but the form of the “Letter” as a whole, is to St. Paul” (Berry 114). Paul’s positive impact in the Christian faith logically encouraged the audience to agree with Dr. King as he compared himself to Paul. The addition of the philosophical, historical, and Biblical references provided several facets in which the audience could reason through Dr. King’s appeal. The final classical appeal that Dr. King used to strengthen his letter was an emotional appeal through detailed descriptions. Most notably, Dr. King described an interaction with his daughter: ...when you suddenly find your tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to your six-year-old daughter why she can’t go to the public amusement park that has just been advertised on television, and see tears welling up in her little eyes when she is told that Funtown is closed to colored children, and see the depressing clouds of inferiority begin to form in her little mental sky, and see her begin to distort her little personality by unconsciously developing a bitterness toward white people... (King 370-371) The sentenced continued in detail of many other discriminatory realities, and became “a classical Ciceronian period, recognized for its capacity to move cumulatively toward an intense emotional and intellectual impact” (Berry 119). He included such descriptive experiences, appealing to the emotional part of his audience. This effectively evoked sadness and righteous anger within his reader, urging his audience to take action. The inclusion of real-life experiences, especially with his daughter, was relatable for many readers, serving as a reminder that innocent children were Johnson 4 even impacted by segregation. Dr. King appealed to his audience’s emotions; he effectively pushed them away from comfortability and laxity. Dr. King engaged a larger audience than simply the clergymen addressed in his letter. The clergymen were directly referenced on multiple occasions within the letter, “My dear Fellow Clergyman, while confined here in the Birmingham city jail, I came across your recent statement calling our present activities “unwise and untimely”” (King 366). Dr. King directly addressed the eight clergymen who criticized his actions during the Birmingham sit-in, but the contents of the letter transcend those eight men and could be applied to the entire general public. “The clergymen functioned rhetorically as a synecdoche, as a representation of the larger audience King wanted to reach, and his decision to respond to their statement and his manner of doing so were both strategic” (Leff & Utley 41). The overall intended audience was greater than just the clergymen. After all, Dr. King would not have written such a response if he only wanted eight men to take action. All Americans reading the letter were incriminated for their laxity, but Dr. King chose to directly reference the clergymen in order to further his intended purpose The specific purpose and personal tone of Dr. King’s letter justified his actions in response to the criticism from the clergymen and called the church to act against injustice. The conclusion of his letter restated his purpose, “Let us all hope that the dark clouds of racial prejudice will soon pass away and the deep fog of misunderstanding will be lifted from our feardrenched communities and in some not too distant tomorrow the radiant stars of love and brotherhood will shine over our great nation with all of their scintillating beauty” (King 383). By ending the letter in a prophetic manner, Dr. King called his audience to change their ways because it directly impacted each individual in the United States. That direct impact was also apparent in Dr. King’s tone: “The invocation of specific individuals as an ostensible audience Johnson 5 allowed King to cultivate a personal tone and to project his personality in a way that would have been impossible in a document address to no one in particular” (Leff & Utley 41). By including a direct audience, Dr. King cultivated an intimate tone in his letter. He used examples from his own life to describe the injustice of segregation, thereby accomplishing his purpose. The main topic of Dr. King’s letter was participation in the Civil Rights Movement. He addressed the nonviolent protests and the ethical issues behind racial inequality in the United States. Some of the ethical issues that he addressed were the unfair treatment of colored people in society and the direct impact on children. Dr. King then discussed why he was in Birmingham and the importance of the chosen time for protest while including a description of the experiences of black people to call attention to the unjust laws unnecessarily holding people captive. Dr. King also addressed the church directly; he urged the church to step out of indifference, see the inequality, and to take action during this time of injustice. The synthesis of topics covered in the letter effectively addressed each portion of the critique by the clergymen, strengthening Dr. King’s argument. Dr. King’s particular syntax in his letter strengthened his overall argument for people to take action. His letter embodied the voice of a prisoner as he described the impact of segregation, all the while predicting the future of the United States while writing with the voice of a prophet. The inclusion of the extended sentence on pages 370-371 was a powerful syntactical move thereby exemplifying the severity of racial discrimination. So much pain in one single sentence created a dramatic effect for the audience. Dr. King chose his words wisely in his letter, not reacting to criticism with words of anger, but he stated, “I must honestly reiterate that I have been disappointed with the church” (King 378). His disappointment implied the potential for the church to change; throughout the entire letter, Dr. King applied “verbal control” Johnson 6 by avoiding accusatory language (Leff & Utley 44). Using both the voice of a prisoner and the voice of a prophet, Dr. King lamented injustice while calling upon the church to be the catalyst of change for the future. Through his “Letter from Birmingham City Jail,” Dr. King invited the church to step out of their comfort zone and take action against the injustice of racial inequality. He applied the classical appeals of ethos, logos, and pathos in order to best persuade his audience to take action. By keeping his audience, both clergy and lay people, in mind, Dr. King most powerfully appeals to the logos side of his readers with the inclusion of philosophical, historical, and Biblical arguments. He incorporated the Bible directly to his cause by comparing himself to St. Paul, directly appealing to his audience. Using rhetorical strategies to develop his argument, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. called his audience to reevaluate the inequality of segregation in order to drive them to take action. Johnson 7 Works Cited Berry, Edward I. “Doing Time: King's ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail.’” Rhetoric & Public Affairs, vol. 8, no. 1, 2005, pp. 109–132. Fulkerson, Richard P. “The Public Letter as a Rhetorical Form: Structure, Logic, and Style in King's ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail.’” Quarterly Journal of Speech, vol. 65, no. 2, 1979, pp. 121–136. King, Martin Luther, Jr. “”Letter from Birmingham City Jail”” Comp. Christopher M. Anson. 75 Readings across the Curriculum: [an Anthology]. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2008. 366-383. Print. Leff, Michael C., and Ebony A. Utley. “Instrumental and Constitutive Rhetoric in Martin Luther King Jr.'s ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail.’” Rhetoric & Public Affairs, vol. 7, no. 1, 2004, pp. 37–52.