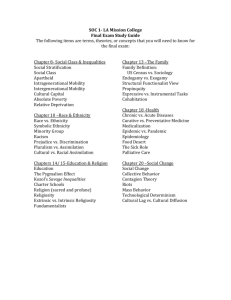

mapp mini dissertation v2FinalCORRECTED

advertisement