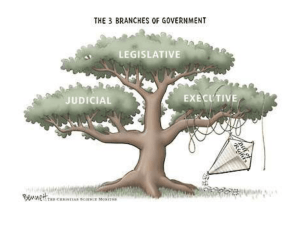

Justiciability & Separation of Powers Outline

advertisement