Aristotle s elements of tragedy plot cha

advertisement

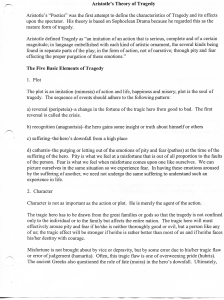

Aristotle’s elements of tragedy: plot, character and thought “Aristotle was the first accurate critic and truest judge – nay, the greatest philosopher the world ever had.” So wrote Ben Jonson, whose assessment is still defensible today. Aristotle was a scholar whose scientific explorations were as wide ranging as his philosophical speculations were profound; a teacher, who enchanted and inspired the brightest youth of Greece; a public figure who lived a turbulent life in a turbulent world. He bestrode antiquity like an intellectual colossus. No man before him had contributed so much to learning. No man after him might aspire to rival his achievements. Aristotle's Poetics is the earliest surviving work of dramatic theory and the first extant philosophical treatise to focus on literary theory. This brief treatise does not deserve attention only for its pioneering qualities or its incisive comments about ancient epic and drama; it has also had a profound effect on the way we read and analyse literature today. In Poetics, Aristotle offers an account of what he calls “poetry.” Once the Poetics was rediscovered and published in about A.D. 1500, its concepts, methods of analysis and conclusions acquired fundamental importance among Renaissance and seventeenth-century dramatists and literary critics in Italy, France and England. Aristotle in Poetics 6 gives us the best explanation we have for our experiences of tragedy. He considers tragedy as the most refined version of poetry that deals with the imitation of lofty matters. The tragedy is one of the poetics arts. According to Aristotle, tragedy came from the efforts of poets to present men as 'nobler,' or 'better' than they are in real life. It is, he says, an imitative representation (mimesis) of a serious (spoudaios) action, dramatically presented in a plot that is self-contained, completed and unified. The protagonists of tragic drama are admirable, not technically speaking heroes or demigods, but larger and better versions of ourselves. In the finest tragedies, the characters of the protagonist make him susceptible to a deflection – to an erring waywardness- that brings disaster, producing a reversal in the projected arc of his life. The story of his undeserved misfortune arouses our pity and fear, clarifying and purifying those reactions in such a way as to bring us both pleasure and understanding. The story contains rhythm and harmony, which occur in different combinations in different parts of the tragedy. It is performed rather than narrated. At its best, tragedy brings recognition of who and what we are. Like other forms of poetry, tragedy is more philosophical and illuminating, and so more truthful than history. Tragedy has “quantitative” parts into which a play can be divided, such as the prologue, epilogue, choral songs, and the acts or episodes. There are also other parts that tragedy has, “qualitative” parts that contribute to its overall function and purpose. So, after defining tragedy Aristotle goes on to list the qualitative parts of the tragedy that contribute to its goal of arousing pity and fear in the audience. First, there are three qualitative parts that pertain to the object of imitation, action. Each tragedy, first and foremost, must have a plot (muthos) which is the arrangement of the incidents or events. It is not identical with the actions that are imitated. We could have a string of actions that are imitated in a tragedy, but there is no plot until those actions are given an order or structure. The plot is so important, that it is the “originating principle and, as it were, the soul of tragedy.” It is the plot that animates the elements in the play, in the way that the soul brings life to the body of an animal, enabling it to carry out the life functions that characterize a particular species. For 1. The tragedy is a representation not of human beings, but of action and life. 2. Without action, a tragedy cannot exist, but without characters, it may. 3. If a poet puts in sequence speeches full of character, well –composed in diction and reasoning, he will not achieve what was the function of tragedy; a tragedy that employs these less adequately, but has a plot will achieve it much more. 4. The most important things with which a tragedy enthralls us are parts of plot – reversals and recognitions 5. A further indication is that people who try their hand at composing can be proficient in the diction and characters before they are able to structure the incidents. The story gets its impact or power only when the incidents are arranged in the correct sequence with an effective link. Following are the specifications of a successful plot of a tragedy:1. Completeness of the plot means the plot must be “a whole,” with a beginning, middle, and an end. The beginning or the incentive moment must instill the cause-and-effect chain based on something which is within the play. The middle, or climax, must be caused by earlier incidents and itself causes the incidents that follow it. The end, or resolution, must be caused by the preceding events, but not lead to other incidents outside the compass of the play. The end should, therefore, solve or resolve the problem created during the incentive moment. There should be the appropriate sequencing of incidents resulting in the feeling of completeness. 2. The magnitude of the plot refers to the length. Usually, the length of the play should be what the viewers can wind up in their memory. At the same time, the lengthy plot with many incidents makes it a complex one. Aristotle recommends complexity of the plot by the inclusion of as many incidents revolving around one theme. The more the number of incidents included in the plot, that make the play richer and improves its artistic value. A brief plot will reduce the scope for artistic value. At the same time, too many incidents without any coherence or sequence will indeed mar the quality of tragedy. Hence, it should be complex, compact and comprehensive. 3. Unity in the plot refers to the unity of action. Whatever the number of incidents or situations discussed in the plot must have an organic unity. The whole action and incidents must be revolving around the central action. The plot may be either simple or complex, although the complex is better. Simple plots have only a “change of fortune” (catastrophe). Complex plots have both “reversal of intention” (peripeteia) and “recognition” (anagnorisis) connected with the catastrophe. He argues that the best plots combine these two as part of their cause-and-effect chain (i.e., the peripeteia leads directly to the anagnorisis); this in turns creates the catastrophe, leading to the final “scene of suffering”. 4. Well determinate structure of the plot means the effective linking of the various events and incidents in the plot with a remarkable coherence. It is the expertise of the poet to prune or avoid all the irrational and irrelevant details from the plot. The whole body of the play must be able to stand as a unit. There should be a perfect sequencing of the events or incidents happening in the play. Whatever the turmoil, the link with which the actions are held together should not be affected. 5. The universality of the plot refers to the fact that whatever that is imitated or shown in the tragedy should be closer to the real life. The inclusion of theme and the associated actions of universal nature will give more significant value to the play, enabling the dramatist catch the attention of more number of people. Next there are two other qualitative parts that pertain to action. Character (ethos) and reasoning (dianoia), which are the two causes of action. By ‘character’ in Poetics 6 Aristotle is not talking about a character’s personality or temperament. Instead, he refers to a concept that comes out of his discussion of virtuous action in his ethics. Character is “that which reveals moral choices”: it is a fixed and established disposition to choose and to avoid certain actions. Character is the source of a person’s motivation and desire. Aristotle explains four qualities for the character of the tragic hero whose actions are imitated to bring about a reversal, recognition and catharsis – the elements that constitute the success of a tragic play. The tragic hero should be good, renowned and prosperous; he should be courageous and dear to everyone, he should be true to life that any one of the audience should be able to identify himself or herself with the feelings or emotions undergone by the hero because whatever is depicted in the play about the hero must make the viewers feel that they are closer to life or real life situations itself; and then the hero should be a consistent person in the sense whatever qualities or weakness assigned to him should be consistently there with him throughout. The adversities that happen to him shouldn’t be an artificially created one as a miracle. All the adversities that he is facing or experiencing due to a reversal of his fortune must be due to some weakness or flaw in his character. The hero is neither an ideal nor a virtuous man, but he is a good man and any one of the viewers can easily identify the hero with any other man among them, that is he must be so much closer to life. His fall doesn’t happen all on a sudden as a shock but it is due to a flaw or frailty in his character which makes the hero more credible in his sufferings. The tragic flaw in the character is known as hamartia. The intensity of the tragedy increases as the character causes some destructions or damages to his kith or kin due to his ignorance of truth, and finally by the pitiful condition of the hero when the truth is informed to him. “Reasoning” is the second cause of action and is brought about by what an agent chooses to do on the basis of what her practical wisdom tells her is the best course of action to accomplish her goals. “Reasoning” or “thought” (dianoia) refers to the rational thoughts of the dramatic personalities, including arguments and deliberations they make, as well as the views they hold. Everything that is supposed to be brought out through the effect of speech or action is included under thought. The verbal and the nonverbal impact of a tragic drama may be assigned to its action or speech, but both these action and speech are the co-existing components of thought. The cathartic effect of the tragic play by arousing the feelings of pity and fear is ultimately the product of thought. In the case of action, no verbal explanation is needed for the intended effect because the action itself is independent to achieve the aim; whereas in the case of speech, the aimed effect has to be achieved by the speech itself which is ultimately depending upon how the character delivers that speech. Dramatic incidents and dramatic speech should be analysed with the same perception since both aims at the same objective.