BMMRS total fetzer book - instrumentation

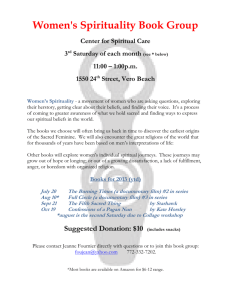

advertisement