2009-24

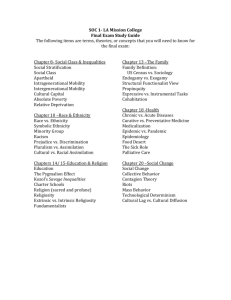

advertisement