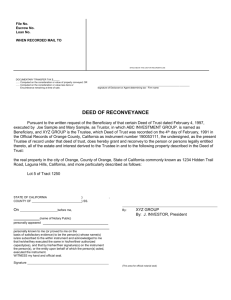

SalesCaseDigests

advertisement