REPORTS

Detection of Pulsed Gamma Rays

Above 100 GeV from the Crab Pulsar

The VERITAS Collaboration; E. Aliu,1 T. Arlen,2 T. Aune,3 M. Beilicke,4 W. Benbow,5 A. Bouvier,3

S. M. Bradbury,6 J. H. Buckley,4 V. Bugaev,4 K. Byrum,7 A. Cannon,8 A. Cesarini,9

J. L. Christiansen,10 L. Ciupik,11 E. Collins-Hughes,8 M. P. Connolly,9 W. Cui,12 R. Dickherber,4

C. Duke,13 M. Errando,1 A. Falcone,14 J. P. Finley,12 G. Finnegan,15 L. Fortson,16 A. Furniss,3

N. Galante,5 D. Gall,22 K. Gibbs,5 G. H. Gillanders,9 S. Godambe,15 S. Griffin,17 J. Grube,11

R. Guenette,17 G. Gyuk,11 D. Hanna,17 J. Holder,18 H. Huan,19 G. Hughes,20 C. M. Hui,15

T. B. Humensky,19 A. Imran,21 P. Kaaret,22 N. Karlsson,16 M. Kertzman,23 D. Kieda,15

H. Krawczynski,4 F. Krennrich,21 M. J. Lang,9 M. Lyutikov,12 A. S Madhavan,21 G. Maier,20

P. Majumdar,2 S. McArthur,4 A. McCann,17* M. McCutcheon,17 P. Moriarty,24 R. Mukherjee,1

P. Nuñez,15 R. A. Ong,2 M. Orr,21 A. N. Otte,3* N. Park,19 J. S. Perkins,5 F. Pizlo,12 M. Pohl,20,25

H. Prokoph,20 J. Quinn,8 K. Ragan,17 L. C. Reyes,19 P. T. Reynolds,26 E. Roache,5

H. J. Rose,6 J. Ruppel,25 D. B. Saxon,18 M. Schroedter,5* G. H. Sembroski,12 G. D. Şentürk,27

A. W. Smith,7 D. Staszak,17 G. Tešić,17 M. Theiling,12 S. Thibadeau,4 K. Tsurusaki,22

J. Tyler,17 A. Varlotta,12 V. V. Vassiliev,2 S. Vincent,15 M. Vivier,18 S. P. Wakely,19 J. E. Ward,8

T. C. Weekes,5 A. Weinstein,21 T. Weisgarber,19 D. A. Williams,3 B. Zitzer7

ulsars were first discovered more than 40

years ago (1) and are now believed to be

rapidly rotating, magnetized neutron stars.

Within the corotating magnetosphere, charged

particles are accelerated to relativistic energies

and emit nonthermal radiation from radio waves

through gamma rays. Although this picture reflects the broad scientific consensus, the details are

still very much a mystery. For example, a number

of models exist that can be distinguished from

each other on the basis of the location of the acceleration zone. Popular examples include the outergap model (2–5), the slot-gap model (6, 7), and

the pair-starved polar-cap model (8–10). One way

to better understand the dynamics within the magnetosphere is through observation of gamma rays

emitted by the accelerated particles.

All of the detected gamma-ray pulsars in (11)

exhibit a break in the spectrum between a few

hundred MeV and a few GeV, with a rapidly fading flux above the break. The break energy is related to the maximum energy of the particles and

to the efficiency of the pair production. Mapping

the cutoff can help to constrain the geometry of

the acceleration region, the gamma-ray radiation

mechanisms, and the attenuation of gamma rays.

Previous measurements of the spectral break are

statistically compatible with an exponential or subexponential cutoff, which is currently the most

favored shape for the spectral break.

One of the most powerful pulsars in gamma

rays is the Crab pulsar (12, 13), PSR J0534 + 2200,

which is the remnant of a historical supernova

P

that was observed in the year 1054. It is located

at a distance of 6500 T 1600 light-years (1 lightyear = 9.46 × 1015 m) and has a rotation period

of ~33 ms, a spin-down power of 4.6 × 1038

erg s−1, and a surface magnetic field of 3.8 ×

1012 G (14, 15). Attempts to detect pulsed gamma rays above 100 GeV from the Crab pulsar

began decades ago (16). Before the work reported here, the highest energy detection was at

25 GeV (17). At higher energies, near 60 GeV,

only hints of pulsed emission have been reported

in two independent observations (17, 18). Although Fermi-LAT measurements of the Crab

pulsar spectrum are consistent, within the errors

of the measurements, with a power law with an

exponential cutoff at about 6 GeV (13), the flux

measurements above 10 GeV are systematically

higher than the fit with an exponential cutoff,

which hints that the spectrum is indeed harder

than a power law with an exponential cutoff

(13, 17). However, the sensitivity of the previous

data was insufficient to allow a definite conclusion about the spectral shape.

We observed the Crab pulsar with the Very

Energetic Radiation Imaging Telescope Array

System (VERITAS) for 107 hours between September 2007 and March 2011. VERITAS is a

ground-based gamma-ray observatory composed

of an array of four atmospheric Cherenkov telescopes located in southern Arizona, USA (19).

VERITAS has a trigger threshold of 100 GeV.

Most of the data, 77.7 hours, were recorded after the relocation in summer 2009 of one of

www.sciencemag.org

SCIENCE

VOL 334

Downloaded from http://science.sciencemag.org/ on January 2, 2019

We report the detection of pulsed gamma rays from the Crab pulsar at energies above

100 giga–electron volts (GeV) with the Very Energetic Radiation Imaging Telescope Array

System (VERITAS) array of atmospheric Cherenkov telescopes. The detection cannot be explained

on the basis of current pulsar models. The photon spectrum of pulsed emission between

100 mega–electron volts and 400 GeV is described by a broken power law that is statistically

preferred over a power law with an exponential cutoff. It is unlikely that the observation can

be explained by invoking curvature radiation as the origin of the observed gamma rays above

100 GeV. Our findings require that these gamma rays be produced more than 10 stellar radii

from the neutron star.

the VERITAS telescopes, which resulted in a

lower energy threshold and better sensitivity of

the array. We processed the recorded atmospheric

shower images with a standard moment analysis (20) and calculated the energy and arrival

direction of the primary particles (21). We then

rejected events caused by charged cosmic-ray

events. For gamma rays, the distribution of the

remaining, or selected, events as a function of

energy peaks at 120 GeV. In the pulsar analysis,

for each selected event, we first transformed the

arrival time to the barycenter of the solar system

and then calculated the spin phase of the Crab

pulsar from the barycentered time using contemporaneously measured spin-down parameters (22, 23). All steps in the analysis have been

cross-checked by an independent software package and are explained in detail in the supporting

online material (SOM). We applied the H test

(24) to evaluate periodic emission at the frequency of the Crab pulsar (SOM). This yielded a test

value of 50, which corresponded to a significance

of 6.0 SD that pulsed emission is present in

the data.

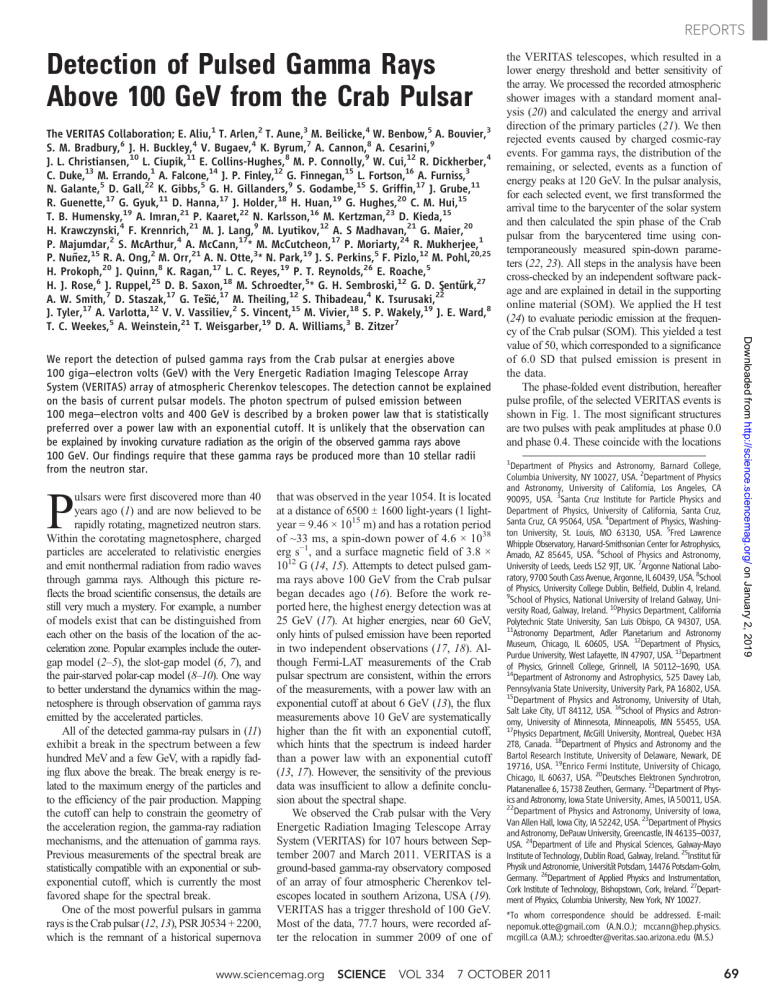

The phase-folded event distribution, hereafter

pulse profile, of the selected VERITAS events is

shown in Fig. 1. The most significant structures

are two pulses with peak amplitudes at phase 0.0

and phase 0.4. These coincide with the locations

1

Department of Physics and Astronomy, Barnard College,

Columbia University, NY 10027, USA. 2Department of Physics

and Astronomy, University of California, Los Angeles, CA

90095, USA. 3Santa Cruz Institute for Particle Physics and

Department of Physics, University of California, Santa Cruz,

Santa Cruz, CA 95064, USA. 4Department of Physics, Washington University, St. Louis, MO 63130, USA. 5Fred Lawrence

Whipple Observatory, Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics,

Amado, AZ 85645, USA. 6School of Physics and Astronomy,

University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK. 7Argonne National Laboratory, 9700 South Cass Avenue, Argonne, IL 60439, USA. 8School

of Physics, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland.

9

School of Physics, National University of Ireland Galway, University Road, Galway, Ireland. 10Physics Department, California

Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, CA 94307, USA.

11

Astronomy Department, Adler Planetarium and Astronomy

Museum, Chicago, IL 60605, USA. 12Department of Physics,

Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907, USA. 13Department

of Physics, Grinnell College, Grinnell, IA 50112–1690, USA.

14

Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 525 Davey Lab,

Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, USA.

15

Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Utah,

Salt Lake City, UT 84112, USA. 16School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA.

17

Physics Department, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec H3A

2T8, Canada. 18Department of Physics and Astronomy and the

Bartol Research Institute, University of Delaware, Newark, DE

19716, USA. 19Enrico Fermi Institute, University of Chicago,

Chicago, IL 60637, USA. 20Deutsches Elektronen Synchrotron,

Platanenallee 6, 15738 Zeuthen, Germany. 21Department of Physics and Astronomy, Iowa State University, Ames, IA 50011, USA.

22

Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Iowa,

Van Allen Hall, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA. 23Department of Physics

and Astronomy, DePauw University, Greencastle, IN 46135–0037,

USA. 24Department of Life and Physical Sciences, Galway-Mayo

Institute of Technology, Dublin Road, Galway, Ireland. 25Institut für

Physik und Astronomie, Universität Potsdam, 14476 Potsdam-Golm,

Germany. 26Department of Applied Physics and Instrumentation,

Cork Institute of Technology, Bishopstown, Cork, Ireland. 27Department of Physics, Columbia University, New York, NY 10027.

*To whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail:

nepomuk.otte@gmail.com (A.N.O.); mccann@hep.physics.

mcgill.ca (A.M.); schroedter@veritas.sao.arizona.edu (M.S.)

7 OCTOBER 2011

69

REPORTS

of the main pulse and interpulse, hereafter P1 and

P2, which are the two main features in the pulse

profile of the Crab pulsar throughout the electromagnetic spectrum. We characterized the pulse

profile using an unbinned maximum-likelihood

fit (SOM). In the fit, the pulses were modeled

with Gaussian functions, and the background

was determined from the events that fell between

phases 0.43 and 0.94 in the pulse profile (referred to as the off-pulse region). The positions

of P1 and P2 in the VERITAS data thus lie at

the phase values – 0.0026 T 0.0028 and 0.3978 T

0.0020, respectively, and are shown by the vertical lines (Fig. 1). The full widths at half maximum (FWHM) of the fitted pulses are 0.0122 T

0.0035 and 0.0267 T 0.0052, respectively. The

pulses are narrower by a factor of two to three

than those measured by the Fermi Large Area

Telescope (Fermi LAT) at 100 MeV (13) (Fig. 1).

If gamma rays observed at the same phase are

emitted by particles that propagate along the same

magnetic field line (25) and if the electric field in

the acceleration region is homogeneous, then a

possible explanation of the observed narrowing

Counts per Bin

A

VERITAS > 120 GeV

3700

3600

3500

3400

3200

2000 -1

1500

Fermi > 100 MeV

-0.5

0

-0.5

0

0.5

500

0

-1

1950

Counts per Bin

B

VERITAS > 120 GeV

1900

P1

1850

0.5

1950

1750

1700

1700

1650

1650

1600

1600

1550

1550

Counts per Bin

1500

-0.05

Fermi > 100 MeV

0

0.05

0.1

Phase

1000

500

-0.1

P2

1850

1750

0

VERITAS > 120 GeV

1900

1800

1500

1

Phase

C

1800

1500

2000-0.1

-0.05

0

0.05

0.1

600

0.3

0.35

Fermi > 100 MeV

Fig. 1. Pulse profile of the Crab pulsar. Phase 0 is the position of P1 in radio.

The shaded histograms show the VERITAS data. The pulse profile in (A) is

shown twice for clarity. The dashed horizontal line shows the background level

estimated from data in the phase region between 0.43 and 0.94. (B and C)

Expanded views of the pulse profile with a finer binning than in (A) and are

centered at P1 and P2, which are the two dominant features in the pulse profile

7 OCTOBER 2011

VOL 334

0.4

0.45

0.5

Phase

400

200

0

0.3

0.35

0.4

0.45

0.5

Phase

Phase

70

1

Phase

1000

Counts per Bin

Counts per Bin

Counts per Bin

3100

of the Crab pulsar. The data above 100 MeV from the Fermi LAT (13, 30) are

shown beneath the VERITAS profile. The vertical dashed lines in the panels (B)

and (C) mark the best-fit peak positions of P1 and P2 in the VERITAS data. The

solid black line shows the result of an unbinned maximum-likelihood fit of

Gaussian functions to the VERITAS pulse profile (described in text). The peak

positions for the Fermi-LAT and the VERITAS data agree within uncertainties.

SCIENCE

www.sciencemag.org

Downloaded from http://science.sciencemag.org/ on January 2, 2019

3300

REPORTS

E2 dF/dE (MeV cm-2 s-1)

10-3

10-4

10-5

10-6

χ2

10-7

20

15

10

5

0

VERITAS, this work

Fermi (Abdo et al, 2010)

MAGIC (Aliu et al. 2008)

MAGIC (Albert et al. 2008)

CELESTE (De Naurois et al. 2002)

STACEE (Oser et al. 2001)

HEGRA (Aharonian et al. 2004)

Whipple (Lessard et al. 2000)

Broken power law fit

Exponential cutoff fit

3

10

Power law with exponential cutoff

5

104

10

4

10

6

10

Energy (MeV)

Broken power law

10

3

10

5

10

6

Energy (MeV)

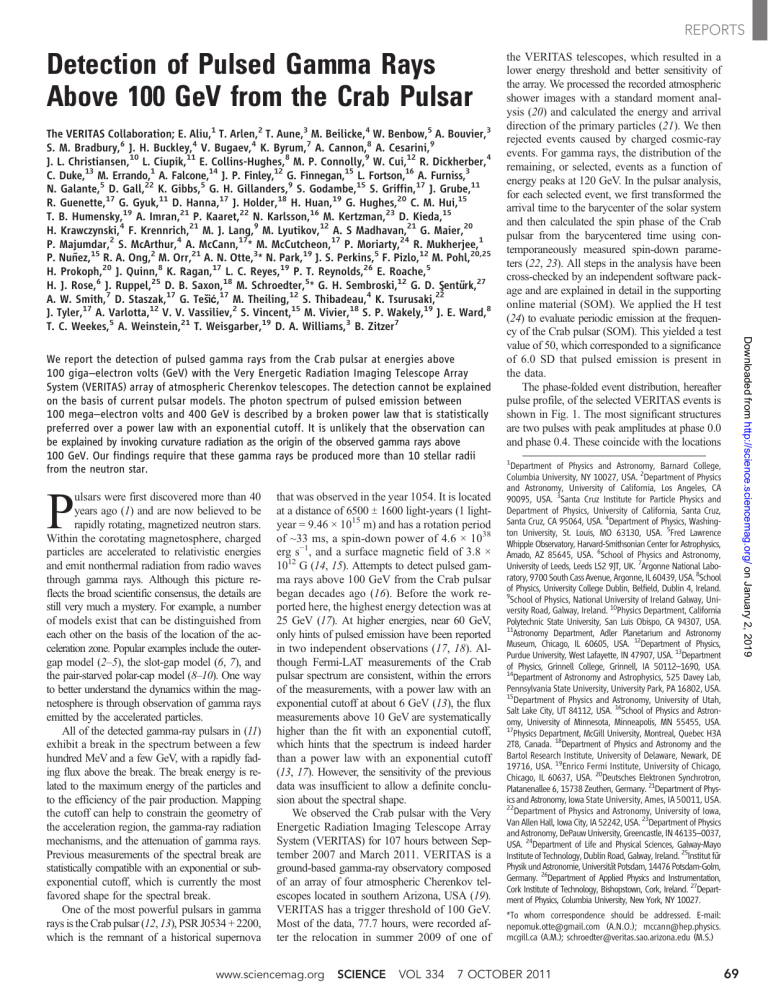

Fig. 2. Spectral energy distribution (SED) of the Crab pulsar in gamma rays. VERITAS flux measurements

are shown by the bowtie. The dotted line enclosed by the bow tie gives the best-fit power-law spectrum and

the statistical uncertainties, respectively, for the VERITAS data using a forward-folding method. The solid

red circles show VERITAS flux measurements using a different spectral reconstruction method (SOM). FermiLAT data (13) are given by green squares, and the MAGIC flux point (17) by the solid reddish triangle. The

open symbols are upper limits from the CErenkov Low-Energy Sampling and Timing Experiment (CELESTE)

(31), the High-Energy-Gamma-Ray Astronomy (HEGRA) experiment (32), MAGIC (18), Solar Tower Atmospheric Cherenkov Effect Experiment (STACEE) (33), and Whipple (29). The result of a fit of the VERITAS

and Fermi-LAT data with a broken power law is given by the solid line, and the result of a fit with a

power-law spectrum multiplied with an exponential cutoff is given by the dashed line. Below the SED,

we plot c2 values to visualize the deviations of the best-fit parameterization from the Fermi-LAT and

VERITAS flux measurements.

www.sciencemag.org

SCIENCE

VOL 334

A(E/E0)aexp(–E/Ec), which is a good parameterization of the Fermi LAT (13) and MAGIC

(17) data. The Fermi-LAT and MAGIC data can

be equally well parameterized by a broken power

law, but those data are not sufficient to significantly distinguish between a broken power law

and an exponential cutoff. The VERITAS data,

on the other hand, clearly favor a broken power

law as a parameterization of the spectral shape.

The fit of the VERITAS and Fermi-LAT data

with a broken power law of the form A(E/E0)a/

[1 + (E/E0)a-b] results in a c2 value of 13.5 for

15 degrees of freedom with the fit parameters

A = (1.45 T 0.15stat ) × 10−5 TeV −1 cm−2 s−1, E0 =

4.0 T 0.5stat GeV, a = –1.96 T 0.02stat and b =

–3.52 T 0.04stat (Fig. 2). A corresponding fit with

a power law and an exponential cutoff yields a

c2 value of 66.8 for 16 degrees of freedom. The

fit probability of 3.6 × 10−8 derived from the c2

value excludes the exponential cutoff as a viable

parameterization of the Crab pulsar spectrum.

The detection of gamma-ray emission above

100 GeV provides strong constraints on the

gamma-ray radiation mechanisms. If one assumes

a balance between acceleration gains and radiative losses by curvature radiation, the break in

the gamma-ray spectrum is expected to be at Ebr =

150 GeV h3/4 sqrt(x), where h is the acceleration

efficiency (h < 1) and x is the radius of curvature

in units of the light-cylinder radius (28) (SOM).

Only in the extreme case of an acceleration field

that is close to the maximum allowed value and a

radius of curvature that is close to the light-cylinder

radius would it be possible to produce gamma-ray

emission above 100 GeV with curvature radiation.

It is, therefore, unlikely that curvature radiation is

the dominant production mechanism of the observed gamma-ray emission above 100 GeV. A

plausible different radiation mechanism is inverseCompton scattering that has motivated previous

searches for pulsed very high energy emission, e.g.,

(29). With regard to the overall gamma-ray production, two possible interpretations are that a single

emission mechanism alternative from curvature

radiation dominates at all gamma-ray energies or

that a second mechanism becomes dominant above

the spectral break energy. It might be possible to

distinguish between the two scenarios with higherresolution spectral measurements above 10 GeV.

Downloaded from http://science.sciencemag.org/ on January 2, 2019

averaged spectrum because no “bridge” emission, which is observed at lower energies, is seen

between P1 and P2 in the VERITAS data. However, the existence of a constant flux component

that originates in the magnetosphere cannot be

excluded and would be indistinguishable from

the gamma-ray flux from the nebula. Figure 2

shows the VERITAS phase-averaged spectrum

together with measurements made with Fermi

LAT and the Major Atmospheric Gamma-ray Imaging Cherenkov telescope (MAGIC). In the energy range between 100 GeV and 400 GeV

measured by VERITAS, the energy spectrum

is well described by a power law F(E) = A(E/150

GeV)a, with A = (4.2 T 0.6stat + 2.4syst – 1.4syst) ×

10−11 TeV −1 cm−2 s−1 and a = –3.8 T 0.5stat T

0.2syst. At 150 GeV, the flux from the pulsar is

~1% of the flux from the nebula. The detection

of pulsed gamma-ray emission between 200 GeV

and 400 GeV, the highest energy flux point, is

only possible if the emission region is at least

10 stellar radii from the star’s surface (26). Using

calculations from (27), the emission region can even

be constrained to be at least 30 to 40 stellar radii.

Combining the VERITAS data with the FermiLAT data we can place a stringent constraint on

the shape of the spectral turnover. The previously favored spectral shape of the Crab pulsar

above 1 GeV was an exponential cutoff F(E) =

is that the region where acceleration occurs tapers.

However, detailed calculations are necessary to

explain fully the observed pulse profile.

Along with the observed differences in the

pulse width, the amplitude of P2 is larger than

P1 in the profile measured with VERITAS, in

contrast to what is observed at lower gamma-ray

energies where P1 dominates (Fig. 1). It is known

that the ratio of the pulse amplitudes changes as

a function of energy above 1 GeV (13) and becomes near unity for the pulse profile integrated

above 25 GeV (17). To quantify the relative intensity of the two peaks above 120 GeV, we integrated the pulsed excess between phase – 0.013

and 0.009 for P1 and between 0.375 and 0.421

for P2. This is the T2 SD interval of each pulse

as determined from the maximum-likelihood fit.

The ratio of the excess events and thus the intensity ratio of P2/P1 is 2.4 T 0.6. If one assumes

that the differential energy spectra of P1 and P2

above 25 GeV can each be described with a

power law, F(E) ~ E a and that the intensity

ratio is exactly unity at 25 GeV (17), then the

spectral index a of P1 must be smaller than the

spectral index of P2 by aP2 – aP1 = 0.56 T 0.16.

We measured the gamma-ray spectrum above

100 GeV by combining the pulsed excess in the

phase regions around P1 and P2. This can be

considered a good approximation of the phase-

References and Notes

1. A. Hewish, S. J. Bell, J. D. H. Pilkington, P. F. Scott,

R. A. Collins, Nature 217, 709 (1968).

2. K. S. Cheng, C. Ho, M. Ruderman, Astrophys. J. 300, 500

(1986).

3. R. W. Romani, Astrophys. J. 470, 469 (1996).

4. K. Hirotani, Astrophys. J. 652, 1475 (2006).

5. A. P. S. Tang, J. Takata, J. Jia, K. S. Cheng, Astrophys. J.

676, 562 (2008).

6. J. Arons, Astrophys. J. 266, 215 (1983).

7. A. G. Muslimov, A. K. Harding, Astrophys. J. 588, 430

(2003).

8. M. Frackowiak, B. Rudak, Adv. Space Res. 35, 1152 (2005).

9. A. K. Harding, V. V. Usov, A. G. Muslimov, Astrophys. J.

622, 531 (2005).

10. C. Venter, A. K. Harding, L. Guillemot, Astrophys. J. 707,

800 (2009).

11. A. Abdo et al., Astrophys. J. 187 (suppl.), 460 (2010).

7 OCTOBER 2011

71

REPORTS

12. J. M. Fierro, P. F. Michelson, P. L. Nolan, D. J. Thompson,

Astrophys. J. 494, 734 (1998).

13. A. Abdo et al., Astrophys. J. 708, 1254 (2010).

14. R. N. Manchester, G. B. Hobbs, A. Teoh, M. Hobbs,

Astron. J. 129, 1993 (2005).

15. ATNF Pulsar Catalogue, www.atnf.csiro.au/people/pulsar/

psrcat/.

16. T. C. Weekes et al., Astrophys. J. 342, 379 (1989).

17. E. Aliu et al.; MAGIC Collaboration, Science 322, 1221

(2008).

18. J. Albert et al., Astrophys. J. 674, 1037 (2008).

19. J. Holder et al., Astropart. Phys. 25, 391 (2006).

20. A. M. Hillas, in Proceedings of the 19th International

Cosmic Ray Conference, La Jolla, CA, 11 to 23 August

1985, p. 445 (ICRC, La Jolla, 1985).

21. P. Cogan, in Proceedings of the 30th International

Cosmic Ray Conference, Mérida, Mexico, 3 to 7 July

2007, vol. 3, p. 1385 (ICRC, Mérida, 2008).

22. A. G. Lyne et al., Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 265, 1003 (1993).

23. Jodrell Bank Crab Pulsar Monthly Ephemeris,

www.jb.man.ac.uk/~pulsar/crab.html.

24.

25.

26.

27.

O. C. de Jager, Astrophys. J. 436, 239 (1994).

X.-N. Bai, A. Spitkovsky, Astrophys. J. 715, 1282 (2010).

M. G. Baring, Adv. Space Res. 33, 552 (2004).

K. J. Lee et al., Mon. Notic. Roy. Astron. Soc. 405, 2103

(2010).

28. M. Lyutikov, A. N. Otte, A. McCann, arXiv:1108.3824

(2011).

29. R. W. Lessard et al., Astrophys. J. 531, 942 (2000).

30. The Fermi-LAT pulse profile of the Crab pulsar above

100 MeV that is shown in Fig. 1 is not the original one

from reference (13) but one that has been calculated

with an updated ephemerides that corrects for a small

phase offset that has been introduced in the original

analysis http://fermi.gsfc.nasa.gov/ssc/data/access/lat/

ephems/0534+2200/README.

31. M. de Naurois et al., Astrophys. J. 566, 343 (2002).

32. F. Aharonian et al., Astrophys. J. 614, 897 (2004).

33. S. Oser et al., Astrophys. J. 547, 949 (2001).

Acknowledgments: This research is supported by grants from

the U.S. Department of Energy, NSF, and the Smithsonian

Institution; by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research

Kumar Varoon,* Xueyi Zhang,* Bahman Elyassi, Damien D. Brewer, Melissa Gettel,†

Sandeep Kumar,‡ J. Alex Lee,§ Sudeep Maheshwari,|| Anudha Mittal, Chun-Yi Sung,

Matteo Cococcioni, Lorraine F. Francis, Alon V. McCormick, K. Andre Mkhoyan, Michael Tsapatsis¶

Thin zeolite films are attractive for a wide range of applications, including molecular sieve

membranes, catalytic membrane reactors, permeation barriers, and low-dielectric-constant

materials. Synthesis of thin zeolite films using high-aspect-ratio zeolite nanosheets is desirable

because of the packing and processing advantages of the nanosheets over isotropic zeolite

nanoparticles. Attempts to obtain a dispersed suspension of zeolite nanosheets via exfoliation

of their lamellar precursors have been hampered because of their structure deterioration and

morphological damage (fragmentation, curling, and aggregation). We demonstrated the synthesis

and structure determination of highly crystalline nanosheets of zeolite frameworks MWW and MFI.

The purity and morphological integrity of these nanosheets allow them to pack well on porous

supports, facilitating the fabrication of molecular sieve membranes.

igh-aspect-ratio zeolite single crystals

with thickness in the nanometer range

(zeolite nanosheets) are desirable for applications including building blocks for heterogeneous catalysts (1–3) and the fabrication of

thin molecular sieve films and nanocomposites

for energy-efficient separations (4). They could

H

Department of Chemical Engineering and Materials Science,

University of Minnesota, 151 Amundson Hall, 421 Washington

Avenue Southeast, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA.

*These authors contributed equally to this work.

†Present address: Department of Chemical and Environmental

Engineering, University of California, Riverside, 1175 West

Blaine Street, Riverside, CA 92507, USA.

‡Present address: Material Analysis Laboratory, Intel Corporation, Hillsboro, OR 97124, USA.

§Present address: Department of Chemical and Biomolecular

Engineering, Rice University, MS-362, 6100 Main Street,

Houston, TX 77005, USA.

||Present address: Schlumberger Doll-Research, Schlumberger

Limited, 1 Hampshire Street, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA.

¶To whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail:

tsapatsis@umn.edu

72

also be of fundamental importance in probing

the mechanical, electronic, transport, and catalytic

properties of microporous networks at the nanoscale (5, 6). Despite steady advances in the preparation and characterization of layered materials

containing microporous layers and of their pillared and swollen analogs (1–3, 7–17), the synthesis of suspensions containing discrete, intact,

nonaggregated zeolite nanosheets has proven

elusive because of structural deterioration and/or

aggregation (18) of the lamellae upon exfoliation.

Here, we report the isolation and structure determination of highly crystalline zeolite nanosheets

of the MWW and MFI structure types, and we

demonstrated the use of their suspensions in the

fabrication of zeolite membranes.

MWW and MFI nanosheets were prepared

starting from their corresponding layered precursors

ITQ-1 (1) and multilamellar silicalite-1 (3), respectively. Before exfoliation by melt blending with

polystyrene (weight-average molecular weight =

45000 g/mol), ITQ-1 was swollen according to a

7 OCTOBER 2011

VOL 334

SCIENCE

Supporting Online Material

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/334/6052/69/DC1

Materials and Methods

SOM Text

Figs. S1 to S4

References (34–36)

10 May 2011; accepted 19 August 2011

10.1126/science.1208192

previously reported procedure (18); multilamellar

silicalite-1 was used as made. Melt blending was

performed under a nitrogen environment in a corotating twin screw extruder with a recirculation

channel (19). The polystyrene nanocomposites

obtained by melt blending were characterized by

x-ray diffraction (XRD), and microtomed sections

were imaged by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to reveal the presence of exfoliated

MWW and MFI nanosheets embedded in the

polymer matrix (figs. S1 and S2).

To obtain a dispersion of these nanosheets,

the nanosheet-polystyrene nanocomposites were

placed in toluene and sonicated. After polymer

dissolution and removal of the larger particles

by centrifugation, the dispersions, containing approximately 1.25% w/w polymer and 0.01% w/w

nanosheets, were used to prepare samples for

TEM and atomic force microscopy (AFM) examination, by drying a droplet on TEM grids and

freshly cleaved mica surfaces, respectively (the

AFM sample was calcined in air at 540°C to

remove polymer). Low-magnification TEM images of high-aspect-ratio MWW and MFI nanosheets reveal their flakelike morphology (Fig. 1,

A and B). The uniform contrast from isolated

nanosheets suggests uniform thickness, whereas

the darker areas can be attributed to overlapping

of neighboring nanosheets. Although lattice fringes

are not easily visible in the high-resolution TEM

(HRTEM) images of the nanosheets (figs. S3A

and B), they do exist, as confirmed by their fast

Fourier transform (FFT) (figs. S3C and D). In

addition, electron diffraction (ED) from single

MWWand MFI nanosheets (Fig. 1, C to E, and G)

and XRD data obtained from calcined powders

of MWW and MFI nanosheets (Fig. 2, A and B)

confirm that the nanosheets are highly crystalline materials of the MWW and MFI type, respectively. The thin dimensions of MWW and

MFI nanosheets, as expected, are along the c

and b axes, respectively, as indicated from the

FFT of the HRTEM images and the ED data.

AFM measurements, calibrated using steps

formed on freshly cleaved mica (20), revealed

www.sciencemag.org

Downloaded from http://science.sciencemag.org/ on January 2, 2019

Dispersible Exfoliated Zeolite

Nanosheets and Their Application

as a Selective Membrane

Council of Canada; by Science Foundation Ireland (SFI

10/RFP/AST2748); and by the Science and Technology

Facilities Council in the United Kingdom. We acknowledge

the excellent work of the technical support staff at the

Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory and at the collaborating

institutions in the construction and operation of the

instrument. A.N.O. was supported in part by a Feodor-Lynen

fellowship of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

We are grateful to M. Roberts and A. Lyne for providing us

with Crab-pulsar ephemerides before the public ones

became available.

Detection of Pulsed Gamma Rays Above 100 GeV from the Crab Pulsar

The VERITAS Collaboration, E. Aliu, T. Arlen, T. Aune, M. Beilicke, W. Benbow, A. Bouvier, S. M. Bradbury, J. H. Buckley, V.

Bugaev, K. Byrum, A. Cannon, A. Cesarini, J. L. Christiansen, L. Ciupik, E. Collins-Hughes, M. P. Connolly, W. Cui, R.

Dickherber, C. Duke, M. Errando, A. Falcone, J. P. Finley, G. Finnegan, L. Fortson, A. Furniss, N. Galante, D. Gall, K. Gibbs,

G. H. Gillanders, S. Godambe, S. Griffin, J. Grube, R. Guenette, G. Gyuk, D. Hanna, J. Holder, H. Huan, G. Hughes, C. M. Hui,

T. B. Humensky, A. Imran, P. Kaaret, N. Karlsson, M. Kertzman, D. Kieda, H. Krawczynski, F. Krennrich, M. J. Lang, M.

Lyutikov, A. S Madhavan, G. Maier, P. Majumdar, S. McArthur, A. McCann, M. McCutcheon, P. Moriarty, R. Mukherjee, P.

Nuñez, R. A. Ong, M. Orr, A. N. Otte, N. Park, J. S. Perkins, F. Pizlo, M. Pohl, H. Prokoph, J. Quinn, K. Ragan, L. C. Reyes, P.

T. Reynolds, E. Roache, H. J. Rose, J. Ruppel, D. B. Saxon, M. Schroedter, G. H. Sembroski, G. D. Sentürk, A. W. Smith, D.

Staszak, G. Tesic, M. Theiling, S. Thibadeau, K. Tsurusaki, J. Tyler, A. Varlotta, V. V. Vassiliev, S. Vincent, M. Vivier, S. P.

Wakely, J. E. Ward, T. C. Weekes, A. Weinstein, T. Weisgarber, D. A. Williams and B. Zitzer

ARTICLE TOOLS

http://science.sciencemag.org/content/334/6052/69

SUPPLEMENTARY

MATERIALS

http://science.sciencemag.org/content/suppl/2011/10/06/334.6052.69.DC2

http://science.sciencemag.org/content/suppl/2011/10/05/334.6052.69.DC1

RELATED

CONTENT

http://science.sciencemag.org/content/sci/334/6052/11.4.full

REFERENCES

This article cites 29 articles, 1 of which you can access for free

http://science.sciencemag.org/content/334/6052/69#BIBL

PERMISSIONS

http://www.sciencemag.org/help/reprints-and-permissions

Use of this article is subject to the Terms of Service

Science (print ISSN 0036-8075; online ISSN 1095-9203) is published by the American Association for the Advancement of

Science, 1200 New York Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20005. 2017 © The Authors, some rights reserved; exclusive

licensee American Association for the Advancement of Science. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. The title

Science is a registered trademark of AAAS.

Downloaded from http://science.sciencemag.org/ on January 2, 2019

Science 334 (6052), 69-72.

DOI: 10.1126/science.1208192