Burial Cultures of Khorasan in Late Bronze Age

advertisement

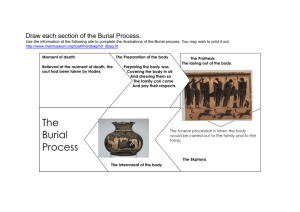

Intl. J. Humanities (2016) Vol. 23 (4): (30-46) Burial Cultures of Khorasan in Late Bronze Age Hassan Basafa1 Received: 2016/5/23 Accepted: 2017/5/6 Abstract The burial process of the deceased is among the most tangible evidence for reconstruction and understanding the culture of human societies, which includes both material and spiritual dimensions. Study of material evidence in archaeological excavations can contribute to partial interpretation of ideological motifs. In this context, recognizing burial practices and interpretation of objects within the grave is a manifestation of human culture and philosophical ideas of the other world, customs, religious beliefs as well as social structure and complexities. There are a few studies available in this field with regard to Great Khorasan, with strategic importance and proximity of several cultural zones around Great Khorasan Ancient Road, although archeological excavations in recent years have resulted in specific material evidence. The current paper includes a structural study of burials in late Bronze Age with a comparative approach encompassing cenotaph, primary, secondary and common human-animal tombs as well as the origin of burial cultures. An assessment of evidences indicates similarity of burial practices of Khorasan in late Bronze period with the advanced culture of BMAC in Central Asia, which has been documented in Afghanistan, Pakistan, South East Iran, Caucasus and south Persian Gulf littoral zone. Keywords: Khorasan; Late Bronze Age; Burial Culture; Central Asia; BMAC. 1 Assistant Professor, Department of Archeology, University of Neyshabour, Khorasan Razavi, Iran, Email: hbasafa@gmail.com 30 Burial Cultures of Khorasan in Late Bronze Age __________ Intl. J. Humanities (2016) Vol. 23 (4) Introduction functionalist Sincethe beginning of the nineteenth components have a function in the society. century contextshave For example, shedding tears is a social from an relationship with the dead (Radcliff- archeological perspective (Fazeli, 2011). Brown, 1964, 117; Metcalf & Huntington, The 1991: 44), which, unlike many other burial ,funerary beenextensivelystudied initial centuryalso years of the marksthe nineteenth firstinitiatives ceremonies, school, is not death and its archaeologically thatwere made to understand the social observable (Morris, 1987). The School of organization of past societies (Kroeber, Symbolism suggests that death is a symbol 1927). then of life, and building an ornamental tomb is introduced as a combination of social a symbol of high status of its constructor identities, as well as a proper distinction to (Morris, 1987). The new process-oriented be (Binford, archaeology is based on a scientific 1971:17). On this basis, Tinter (1978) approach to study burial practices, and suggested thatburial practices may reflect deal with the intercultural burial rites to the complexity of a society. He noted that extract a variety of burials and their a greater amount of energy had been function among the groups (Trigger, 1989, devotedtoindividual 302; Saxe, 1970: 49). The burial practices Social considered character after was death class ranking in burial.This has also beensupported by have Frankenstein and Rowlands (1978) who supporters of the process-oriented school stated that grave gifts might be a sign of (Carr, 1995; Pearson, 2000) as a direct strength and ranking .Various studies have cause and effect relationship between been conducted on the spatial dimension in social structure and life with spatial burial .Coles&Harding, organization of the dead, which might not 1979)as well as onthe spatial distribution have been practiced in several other of artifacts and skeletons in graves(Pader, societies (Larsson, 2003).Burials help 1980). recognize part of prehistoric culture, and practices (e.g been recently introduced by The evolutionary school of thought reflect ideas as well as cultural and social considers death and its attributes as structures of communities. Identification evolving cultural elements (Frazer, 1924; of material evidence of burials and their Bartel, 1982; Metcalf & Huntington, practices leads to non-material component 1991). The sociological school regards of culture and specifies the social and death as a social process, not as an event economic status of the deceased (Masson, (Hertz, 1976: 57-156). An outlook of cognitive 1907). According to the 31 Basafa, H __________________________________ Intl. J. Humanities (2016) Vol. 23 (4): (30-46) archaeological studies, with an approach to which burial, for the first time, formulates the subgroups two criteria of poverty and wealth to bearing data with analyze burials and make grounds for the aspects associated with specialized activity study of social classes in communities. of the buried, personal ornaments and Later, at a conference in Leningrad in grave gifts. sometimes have including numerous funerary objects, practical and ritual 1972, in addition to motives and adding The majority of data concerns western new approaches to this branch, the two regions of Central Asia with respect to factors of gender and age were also identification of the Bronze Age burial considered (Alekshin, 1983: 138). In this culture in the east zone such as Great respect, some archaeologists in their Khorasan since from the beginning of qualitative, sociological and philosophical excavations studies three archaeologists analyzed and interpreted categories: men, women and children, a cultural materials through researches using classification with its own challenges. sociological approach (Artamanov, 1968, They believed that not only wealth and Alekshin, 1983: 137) and then with new poverty indices should be considered to archaeological approaches from 1960s determine the social status of the deceased onwards (Firouzmandi and LabafKhaniki, but the age and sex of the buried should be 2006: 67). In contrast, these studies have regarded since the burial objects are never been conducted in the rich and vast interconnected with both age and sex of zone of Khorasan and there was no clear the buried. Depending on sex, age and framework for pre-Islamic cultures until professional activities of the buried in their the last decade. In this regard, the studies life, related objects were buried along with in them (Binford, 1971: 13-15). It should be conducted with respect to patterns of noted that several models can be drawn up neighboring cultures, especially Central to classify graves, with each bearing Asia. In recent years, excavations in complementary information, in relation to Shahrak-e Firoozeh from 2009 to 2014 and social non-material the historic site of QaraCheshmeh in dimensions of human societies. In funerary 2015 in Neyshabur Plain by the author, the archaeology studies, elements such as the Chalo site in Sankhast (Vahdati, 2011; type and manner of burial, rituals and Vahdatiand ceremonies, shape and structure of tomb 2014; 2015),TepeDamghani in Sabzevar and grave goods should be considered, (Vahdati et al. 2010), TepeQal’eh Khan divided complexity tombs and into 32 this in zone early have 1930s, been Russian inevitably Biscione, Burial Cultures of Khorasan in Late Bronze Age __________ Intl. J. Humanities (2016) Vol. 23 (4) (Judi et al., 2011) and TepeEshgh pit graves with heated beds, tombs with (Vahdati, 2014: 19-27) in Bojnourd and architectural and barrel structure. In terms Razeh-ye Ferdows site (Soroush and of burial practice, each of these types has Rezai, 2014: 271-273), led to a new subgroups such as cenotaph, primary, though insufficient definition of pre- secondary historic patterns and cultures has. animal. Further, Based on archaeological materials acquired during the and common there has humanalso been several branches including primary and aforementioned secondary pit graves, with some having studies, several qualitative studies can simple and heated beds. be set in different fields, including burials of this cultural zone in the late Bronze Pit Graves period. The late Bronze Age which begins Pit graves have been used by societies and from late third millennium BC to early cultural zones for the time immemorial first millenniumBC, a culture known as and account for the largest population. Bactria Margiana Archaeological Their structure is composed of a pit Complex, has designated in irregularly excavated by hand. This has cultural caused accelerated decomposition process period (2300- 1700 BC) emerged in due to contact of the buried with soil. Central Asia and extended to a large part There are a large number of pitgraves in of its the New Bronze Age in the Khorasan surroundings. Accordingly, in this paper cultural zone, which are divided into that is the first of its kind, the burial simple pit graves and pit graves with practices of thelate Bronze Age in heated or burnt bed according to funerary Khorasan a rituals. Examples of the graves with heated comparative approach and the effort was bed have been reported from Shahrak-e made to investigate the origin of burial Firoozeh (Basafa, 2014) and the simple pit practices there. graves from Shahrak-e Firoozeh site archaeological Iranian have been literature. This Plateau been and typified by (Basafa, 2014), Chalo (Vahdati and Structural Study of Burials Biscione, 2015), Razeh (Soroush and In terms ofstructure, burials of the late Rezai, 2014), Qal’eh Khan (Judi and Bronze Age in Khorasan region are Rezaei, 2011) and Damghani (Vahdati et divided to three types: pit graves, tombs al., 2010). with architectural and barrel structure and in a more specialized view include simple 33 Basafa, H __________________________________ Intl. J. Humanities (2016) Vol. 23 (4): (30-46) Grave with Architectural Structure neighboring It emerged and prevailed during Bronze ShahrakeFiroozeh site (Basafa, 2014: 257- Age, especially the final phase of the 266), GoharTepe (Moradi, 2013: 98-100 Bronze Age and has been reported form and Tables, 4-27, 4-28 and 4-29) and sites such as Qal’eh Khan (Judi et al 2011: ShahreSukhteh, which are known as bowl 5, 6, 12 and 13, Figure 2 and 3) from graves Khorasan. Such tombs have also been 2015; Sajadi, reported in numerous cultural zones, 138;SeyedSajjad, 2007). including Shahr-e Soukhteh regions, (Keshavarz and including Nezami, 2009: in southeastern Iran (Keshavarz and Nezami Culture and Burial Practices 2015, SeyedSajjadi 2007: 481; Sajadi According 2009), Pakistan (Danni and Duranni, in Khorasan, different burial cultures of 1964), the GonurTepe in Central Asia late to archaeological researches Bronze period have been (Sarianidi 2007, 2008) GoharTepe in detected with close similarity Mazandaran (Moradi 2013: 101-103V with neighboring regions, including Tables Central 4-30, 4-31 TepeHissar and 4-32) in and Damghan Asia (Bactria Margiana Archaeological Complex), the Sistan and (Schmidt: 1933 P.CXI,P.CXLIX). Kerman zone in Southeastern Iran, South and Southeast of Caspian Sea, Pakistan Barrel Grave and even Before the Bronze Age, this burial practice Makran. Funerary cultures of Khorasan in was used in the Middle East to bury the late Bronze Age can be classified into children and babies. In the early Bronze four groups: 1) Primary; 2) Secondary; 3) Age, with the emergence of complexity in Common human-animal and 4) Cenotaph; all aspects of human society, especially which religious beliefs, this burial practice was structures. have the been cultural zone of detected in different used for all male and female adults as well as children and after the emergence of pit Elementary Burial with Simple Pit graves, a significant percentage of burial Grave Structure practices still It is among the most common practices were type (Ref. Alekshin, of barrel 1983: grave 139- reported from numerous sites 151). Examples of this practice in the final in Khorasan, phase of Bronze Age have been reported including ShahrakeFiroozeh (Basafa, 2014 from the cultural zone of Khorasan and : 257-266), QaraCheshmeh (Basafa, 2015), 34 Burial Cultures of Khorasan in Late Bronze Age __________ Intl. J. Humanities (2016) Vol. 23 (4) Chalo (Vahdati and Bishuneh, 2015), human Damghani (Vahdati et al., 2010), Qal’eh Turkmenistan, which are often irregular, Khan (Judi et al., 2011), TepeEshgh incomplete (secondary) and belong to (Vahdati, 2014), Razeh (Soroush and people Yousefi, 2014) and neighboring areas such disability (Sarianidi, 2007: 36-38). as Tepe Hissar skeletons with in GonurTepe physical defects in and (Schmidt, 1933), BazgirTepe(Abbasi, 2015), NargesTepe Secondary Burials (Abbasi, 2012), TurengTepe (Deshayes, This type of burial is considered a popular 1968, Boucharlat and Lecomte, 1987) and tradition in Great Khorasan and Central Shah Tepe (Arne, 1945) in the Gorgan Asia and its examples have been reported Plain, GoharTepe of Mazandaran (Moradi, from 2013), Shahdad (Hakemi, 2006) and (Sarianidi, 2007: 31,50), and the Shahrak-e TepeYahya (Karlovsky, 2009) in Kerman, Firoozeh ShahreSukhteh (Keshavarz and Nezami, 2014: 258-260) with two structures of pit 2015; grave and barrel. Sajjadi, 2009), GonurTepe GonurTepe site in in Turkmenistan Neyshabur (Basafa (Sarianidi, 2008, 2007) and NamazgaTepe (Alekshin, 1983) DashliTepe and in Turkmenistan, SapalliTepe Cenotaph of This is a tomb lacking corpse and erected Afghanistan (Sarianidi, 1984), the Miri- as a monument. This type of burial with Qalat site in Makran (Besenval, 1997) and thepit grave structure has been reported Pakistan (Dani and Durrani, 1964). from Shahrak-e (Basafa, 2014: 262-264; Firoozeh Fig. 4 Elementary Burial with Heated Grave and 5), Chalo (Vahdati, 2014: 321 and Pit Structure 2015: 520), Shahdad5 (Hakemi, 2006: 84- Pit graves with burnt bed have been 120), Sibri, Quetta (Santoni, 1981: 52- reported from the cultural zones of Central 60) and in the tomb with crypt architecture Asia in GonurTepeh (Sarianidi, 2007: 54) from and Khorasan in Shahrak-e Firoozeh (Sarianidi, 2007: (Basafa, 2014:257-266) and are somewhat leading compatible with the tradition of cremation. believes that burial practices of GonurTepe Burial with the heated pit grave structure in Turkmenistan in the New Bronze period in the Khorasan zone in Shahrak-e have been associated with Zoroastrian Firoozeh cenotaph ideas (Sarianidi, 2007: 50). Based on the type (Basafa, 2014: 256-262) but includes description of funeral in the Zoroastrian site is of the 35 GonurTepe Russian in 31, Turkmenistan Table VI). The archaeologist,Sariandi Basafa, H __________________________________ Intl. J. Humanities (2016) Vol. 23 (4): (30-46) belief, it has been mentioned that “after 1394: 520). Examples of common human- death, Dorjnasu gallops over the dead animal burials have so far been retrieved body like a fly during which the corpse from TepeEshgh (Vahdati, 2014), Chalo turns foul and corrupt (Vandidad, 7/2; see (Vahdati and Bishuneh, 2015: 520) and Mehdizadeh, outside Khorasan from Shahr-e Soukhteh 2000: 359); then, after prayer, the corpse is (Sajjad, 2007: grave number 1003; Sajjadi taken into silence or 2009; Tosi 2006) and areas under the tower and waited for vultures and buzzards influence of the BMAC culture, including to strip the corpse of skin and flesh, after GonurTepe in Turkmenistan (Sarianidi, which the bones are dumped into the well 2007: 147), SapalliTepe (Sarianidi, 2001: in the middle of the Tower of Silence or 434), Jarkutan and one sample from buried (Mehdizadeh, 2000: 361)”. With Sarazam in Tajikistan. crypt this interpretation, the secondary burial, In Vandidad, a special location known cenotaphs as well as secondary graves can as Kata has been mentioned that is the be house of dead and another place has been equaled mentioned to the the aforementioned Zoroastrian funerary cited to be the most bitter grief house as a traditions, since they are compatible with burial place of cadavers of dead people dumping the bones of the deceased into the and dogs (Vandidad, 7/3-11). This section well in the middle of the Tower of Silence of Vandidad that refers to common burial in Zoroastrian burial rites or burial of place of human and animal cadavers bones after the decomposition of flesh and (including skin in the secondary burial. between Zoroastrian ideas and funerary dogs) represents the link traditions of common human and animal Common Human-Animal Burial burial. Typical examples include burial of This is a burial practice of the late Bronze human and dog from TepeEshgh in Age in Khorasan as well as areas under the Bojnord (Vahdati, 2014,) ShahreSukhteh influence of the BMAC culture. Basically, in Sistan (SeyedSajjad, 2007, 2009: grave animals buried together with human number 1003) as well as human and goat corpses are domestic animals such as burial from Chalo site (Vahdati and goats, sheep, dogs and horses. In some Bishuneh, 2015). cases, individual animal burials have been found in cemeteries of the late Bronze Discussion Age, including Chalo site in Khorasan The growing culture of early urbanization region in western Central Asia continued during (Vahdati and Biscione, 36 Burial Cultures of Khorasan in Late Bronze Age __________ Intl. J. Humanities (2016) Vol. 23 (4) the Middle Bronze Age (2500-1800 BC) Merv and turned into finished goods on a and cultural large scale (Ibid: 192). Before excavations developments and economic relations with of the past decade in Khorasan, typical neighboring countries was expanded as cultural materials of BMAC were reported early as the third millennium BC (Vahdati, from 2015: 41). Expanding urban population in including Hissar, TurengTepe and Shah the foothills of the KopetDaghMountains Tepe (TahmasebiZaveh, during the Namazga V period resulted in 3). Exploration of locations associated the formation of a significant cultural with the BMAC culture in Khorasan has phenomenon during the Late Bronze addressed new data and assumptions on period, referred to as Bactria Margiana the indigenous nature of this culture in Archaeological Complex (Namazga VI). Khorasan and its expansion to surrounding The materials of the BMAC culture were areas and the result of this research also soon found their way out of the Oxus basin reinforces some aspects of this hypothesis. and northern foothills of KopetDagh and The most important cultural materials expanded to vast areas of the Iranian indicating the expansion of the BMAC plateau and surrounding regions, which is culture to neighboring areas have been considered the dominant culture of the obtained from funerary contexts. Burial Bronze Age in Central Asia and indicates and its requirements, including cultural an extensive exchange area the Oxus materials and structure, are effective data civilization has been associated with to (Hiebert, 1988: 7-151). of communities. For the rising trend of sites of reconstruct northeastern Iran, 2015: the social the fabric first time, There are two important points in the Alekshin dealt with the study of burial advanced BMAC culture. The first is the cultures of Central Asia with a new origin and formation of this culture and the approach. He believes that during late second is its influence zone. Sarianidi, the Bronze Russian archaeologist who has explored corresponding with cultural phase of many aspects of this culture, believes that Namazga VI, a the Iranian plateau is the origin of the emerges and funerary objects also take a BMAC more culture (Sarianidi, 1998: 140). Other rely on endogenous (Hiebert, 1995: 199) while in new Turkmenistan burial modern nature, so tradition that new researchers ornaments like bronze bracelets, rings, transformation earrings and hairpins replace bronze blades some and others believe that raw materials entered into other accessories of previous periods, and he attributes this innovation to 37 Age Basafa, H __________________________________ Intl. J. Humanities (2016) Vol. 23 (4): (30-46) new cultural influence from western The regions GonurTepe are limited (3 types) and not a of secondary burial practices in Turkmenistan (Alekshin, 1983: 138). This common funerary tradition of this culture is while bronze bracelets that are the most (Sarianidi, 2007: 31) and the explorer of important funerary objects of the BMAC this culture believes that the importation of culture from the this practice in GonurTepe and Togolok Middle Bronze Age culture in North East site can be justified (Sarianidi, 1990: 160, of Iran (Hissar) as well as South and South N.2).The barrel graves with a different East of the Caspian Sea (GoharTepe and structure as bowl burials in Shahr-e NargesTepe) (Moradi, 2013: 38 and Table Soukhteh first appeared in the new Bronze 4.3; Age and barrel burials of South and South Abbasi, 2011: 122; Schmidt, 1933: P.IV), East and such objects probably continued and first emerged in late Bronze Age (Moradi, spread as a traditional symbol in burials of 2013: 43). This is despite the fact that the the late Bronze Age in Khorasan and the secondary burials region region (ShahrakeFiroozeh) is have under been the BMAC culture. In reported influence the Caspian Sea also in Khorasan of barrel secondary grave type and reflects continued burial burials have been found in GonurTepe, practices before the new Bronze Age, and which is considered an innovation in their addition, of of explorer Sariandi believes that these burial cultures are associated funerary traditions of Central Asia. with customs and traditions of the Zoroastrian On the other hand, the human-animal burial (Sarianidi, 2007: 50). burial is among the most common funerary This hypothesis is somewhat reliable practices of the BMAC culture. With according Age regard to the proposed date of common iconography of East Iran and Central human-animal burial in the Sarzam region Asian works (Sarianidi, 1998 and 1987). of Tajikistan, which dates back to the end Secondary in of the fourth millennium and the early Turkmenistan and Shahr-e Soukhteh in third millennium BC according to explorer Sistan (SeyedSajjad, 2007, 2009, of this culture, highlighting the history of Grave 609) have the structure of pit graves this burial culture in Tajikistan, it could be and some have architecture. Barrel burials inferred that the origin of this burial were prevalent before the tradition was cultural regions of southern Age in to the late burials different of places Bronze GonurTepe newBronze and regions, Tajikistan. It is most likely that this burial especially in the foothills of KopetDagh. tradition continued and spread in the late 38 Burial Cultures of Khorasan in Late Bronze Age __________ Intl. J. Humanities (2016) Vol. 23 (4) Bronze Age to cenotaphs, which have emerged with Great different structures in burial cultures of the Khorasan, the region influenced by the GonurTepe community in more recent BMAC culture and Central Asia. periods. In addition, in the Chalo site, a neighboring regions, especially Cenotaphs with a variety of structures cenotaph with local objects of Gorgan have been found in GonurTepe in Central Plain Asia but show only the pit grave structure type (Vahdati, 2014: 321) has been found, in which implies the indigenous nature of this Khorasan Firoozeh region site and in Shahrak-e Neyshabur. Some gray clay and Hissar IIIC burial tradition in the Khorasan region. archaeologists believe that the tombs without skeleton have been dedicated to Results people with a special social status; The late Bronze Age burials in the however, an Khorasan region indicate a close cultural exception since no dignity goods have homogeneity of burial traditions of this been found, which can contribute to proper zone with areas under the influence of the understanding of the social status of that BMAC culture as well as cultural zones of type of burial. It should be noted that South and South East of the Caspian Sea. burials from Some of these cultural traditions have been GonurTepe in graves with a pit structure common in Great Khorasan from the Early were probably related to lower classes of Bronze Age and have influenced the the society. Given the number and pit surrounding regions, including Central structure of cenotaphs of the Shahrak-e Asia and southeast of Caspian Sea in a Firoozeh site relative to archaeological later period (late Bronze Age) during sites in Central Asia, it is clear that the communication processes, cultural ties, basic structure of this burial tradition (pit spread of communities, individuals, ideas graves) has been used in Shahrak-e and beliefs. Among burial cultures which Firoozeh, universally can be currently mentioned to have been Shahrak-e disseminated into surrounding areas from Shahrak-e of this Firoozeh type indicating in is retrieved a prevalent tradition the Firoozeh community. Accordingly, this Great Khorasan based on the bulk of burial tradition cannot be limited to the recent studies a) is barrel graves appearing people with a high social status, but burials in the late Bronze Age in sites such as of this type with a variety of structures EshghTepe (including chest and crypt) in GonurTepe NargesTepe in Gorgan Plain for the first can be considered an innovation to time as a new tradition b) according to 39 in Mazandaran and Basafa, H __________________________________ Intl. J. Humanities (2016) Vol. 23 (4): (30-46) results of absolute chronology and has always been assumed to be funerary findings of Shahrak-e Firoozeh unidirectional; the current qualitative and site in Neyshabur Plain indicating older quantitative age of some phases of this site relative to cultural sphere of Great Khorasan have GonurTepe in Turkmenistan. Moreover, paved the way to revise the assumption by comparing the size of explorations in that interactions of the late Bronze Age Shahrak-e Firoozeh and GonurTepe, it can have originated from Central Asia. Up to be burial now, studies on dissemination, interaction traditions as well as cenotaphs in the burial and cultural ties of Central Asia during the context of Shahrak-e Firoozeh with overall late Bronze Age (BMAC culture) with initial structure of burial pits represented neighboring by tombs containing local objects of on iconography Gorgan Plain gray clay and Hissar IIIC in dignity and luxury objects while a majority the Chalo site penetrated in late Bronze of these objects have been retrieved from Age funerary contexts and are considered the said that secondary during communication and archaeological regions have and studies in been based homogeneity of dissemination process in areas under the most influence of the BMAC culture- especially bearing cultural, social and even economic GonurTepe in Turkmensitan and merged and political data. What can be concluded with indigenous-local burial structures of from this research is the indigenous source these areas and eventually led to burial of some burial cultures of Khorasan in the innovations such as cenotaph with chest late Bronze Age that penetrated into and neighboring crypt secondary (catacomb) areas, typical especially findings Central Asia and West Khorasan cultural zones structures. This is while the interaction such as Gorgan Plain and southern regions between BMAC cultures with neighboring of the Caspian Sea through dissemination areas and communication processes in material always with and and diverse has burials structure important been deemed unidirectional from Central Asia to other (funerary cultural points while absolute chronology spiritual (funerary customs and ideologies) and dimensions. cultural materials of Shahrak-e structures) and Firoozeh indicate older age of some phases relative to GonurTepe and BMAC sites of References Central Asia. [1] Abbasi G., (2015). Archaeological Given that the interaction between the achievements BMAC culture and neighboring regions Great Gorgan (Varkan). Tehran:Iranian Negah Press. 40 of Burial Cultures of Khorasan in Late Bronze Age __________ Intl. J. Humanities (2016) Vol. 23 (4) [2] Abbasi, G., (2011). Final Report of Archaeological Analysis of Mortuary Archaeological Practices.Journal of Anthropological Excavations NargesTeppe in in Archaeology, 1, 32-58. Gorgan Plain. GanjinehNghshejahanPublications, [8] Besenval, R., (1997). New Data for Cultural and the Chronology of the Protohistory of and Kech-Makran (Pakistan) from Miri Qalat GolestanInstitution of Higher Learning, 1996 and ShahiTump 1997 Field-Seasons. Gorgan. South Asian Archaeology, 1, 161-187. [3] Alekshin, V.A., Bartel, B., Dolitsky, [9] Boucharlat, R. and Lecomte, O., A.B., Gilman, A., Kohl, P.L., Liversage, (1987). Fouilles de TurengTepe sous la D. and Masset, C., (1983). Burial Customs direction as periodessassanidesetislamiques, Paris. Heritage, Tourism an Handicrafts Organization Archaeological Source [and de Jean Deshayes 1.Les Comments].Current Anthropology, 137- [10]Binford, 149. Practices: Their Study and their Potential, [4] Arne, T.J., (1945). Excavation at Shah Memoirs of the Society for American Tepe, Iran. Archaeology, No. 25, Approaches to the Artamanow, JK. 1968. E., (1971). Mortuary Social Dimensions of Mortuary Practices, Proieohokdienijeekifekogoiakuatua, 6-29. "SowietskajaArchieołogia". Nr 4: 32. [11] [5] Basafa, H., (2015). Exploration report Practices, their Social, Philosophical- of QaraCheshmeh site (KalateShoori) in religious, Circumstantial, and Physical Neyshabur Plain. Archive of Cultural Ddeterminants.Journal Heritage, Archaeological Method and Theory, 2: Handicrafts and Tourism Carr, C.,(1995). Mortuary of Organization. Unpublished. 2, 105-200. [6] Basafa, H., (2014). Late Bronze Age [12] Coles, J. & Harding, A.,(1979). burial practices in Neyshabur Plain (North The Bronze Age in Europe. Methuen, East of Iran). Proceedings of the Fourth London. Dajani, R. 1964. Iron Age International Tombs Conference of Young from Irbid.Annual of the Archaeologists (Mohammad Department of Antiquities of Jordan, 8, HosseinAziziKhranq, Reza Nasseri and 99-101. MortezaKhanipour). Tehran: University of [13] Dani, A.H. and Durrani, F.A., (1964). Tehran. 257-266. A [7] Bartel, B.,(1982). A Historical Pakistan.Asian Perspectives, 8(1), 164- Review 165. of Ethnological and 41 New Grave Complex in West Basafa, H __________________________________ Intl. J. Humanities (2016) Vol. 23 (4): (30-46) [14] Deshayes, J., (1968). TurengTepe Language, Material Culture and Ethnicity, and the plain of Gorgan in the Bronze 1, P.190. Age.Archaeologia Viva, 1, 35-38. [22] Hiebert, F.T., (1998). Central Asians [15] Fazeli, H.,(2011). An Investigation of on the Iranian Plateau: a model for Indo- Craft Cultural Iranian expansionism. The Bronze and Complexity of the Late Neolithic and early Iron Age peoples of eastern central Chalcolithic Periods in the Tehran Plain, Asia, 1, 148-161.Lamberg Karlovsky, PhD Dissertation, University of Bradford C.C., 1994. Central Asian Bronze Age – (UK). Special Section, Antiquity, Vol. 68, 353- Specialization [16] and FirouzmandiShirejini, B and 354. LabafKhaniki M., (2006). Social Structure [23] Judi K, Garazhyan O, and Rezaei of Scythian Communities regarding Burial M., (2011). Prehistoric Burial Practices in Practices. Journal of Tehran University Ghale Khan Settlement (North Khorasan) Faculty of Letters and Science. 5 (57), 67- with an Emphasis on Bronze Age. Journal 92. of Archaeologist Message (15), 57-72. [17] Frankenstein, S. & Rowlands, M., [24] Karlovsky, Lemberg CC., (2009). (1978). The Internal Structure and The Beginning and Flourishing of Culture Regional Context of Early Iron Age and Civilization in South East of Iran Society (Soghan in South-Western Valley Area-Kerman, Germany.Bulletin of the Institute of YahyaCulture: Early Historic Period). Vol Archaeology, University of London., 1.Translated by [24] GholamaliShamloo Pp.15, 73-112. (edited [18] Frazer, J.,(1924). The Belief in Miri). Tehran: Immortality and the Worship of the Department Dead.London: Macmillan Organization. [19] Gilmour, Burials in G.,(2002). Late by Mohammad Reza Publication Planning Cultural Heritage of Foreign [25] Keshavarz, G and SanadgolNezami Age M., (2015). The Structure and Location of Bronze Palestine.Near Eastern Archaeology, Crypt 65: 2, 112-119. Ceremonies [20] Hertz, R.,(1907). Death and the Right Sukhteh. Proceedings Hand.London: Cohen and West. Conference of Archaeology in Birjand [21] Hiebert, F.T., (1995). South Asia (Edited from a Central Asian Perspective.The HashemiZarjabadi). University of Birjand, Indo-Aryans Code 81. of Ancient South Asia: 42 Burials and their in by of Interment Shahre the National Hassan Burial Cultures of Khorasan in Late Bronze Age __________ Intl. J. Humanities (2016) Vol. 23 (4) [26] Moradi, E., (2013). Comparative [34] Pearson, M.,(2000). The studies of Bronze Age burial patterns in Archaeology of outskirts of South and South East of Burial.United States:Texas Caspian Sea with a focus on Gohar University Press. Tepe. Master's thesis. University of Sistan [35] Radcliff-Brown, A.,(1964). The and Baluchistan. Adaman Islanders. Free Press, New [27] Larsson, A.,(2003). Secondary York. Rast, W. 1999.Society and burial practices in the Neolithic: causes mortuary and Dhra.Archaeology, consequences.Current Swedish customs Death at Bab and A&M edh- History and Archaeology, 11, 153-170. Culture in Palestine and the Near [28]Leningrad.J.,(1967).Catal H A za East.Essays in Memory of Albert E. Neolithic Glock. Ed. T. Kapitan. (ASOR Books, Town in Anatolia.London: Thames and Hudson. 3.) [29] Mehdizadeh, A.,(2000). Death and [36] Santoni, M., (1981).Sibri and the Funeral in MazdeanReligion. Faculty of South Cemetery of Mehrgarh: Third Literature millennium and Humanities, Tehran Connections between the University. Spring and Summer, 354-369. Northern Kutch Plain (Pakistan) and [30] Masson. V., (1976).The econonzics Central Asia, South Asian Archaeology, and social sfrztctzlre of ancient societies 52-61. (in Russian). [37] Sarianidi, V.I., (2008). The Palace- [31] Metcalf, B. & Huntington, Temple Complex of North R.,(1991). Celebrations of Death.The Gonur.Anthropology & Archeology of Anthropology of Mortuary Ritual.New Eurasia, 47(1), 8-35. York: Cambridge University Press. [38] Sarianidi, V.I., (2007). Necropolis of [32] Morris, I.,(1987). Burial and Gonur.Kapon. Ancient Society.New York:Cambridge [39] Sarianidi, V.I., (2001). Necropolis of University Press. Gonur and Iranian Paganism.Moscow. [33] Pader, E.,(1980). Material [40] Sarianidi, V.I., (1998). Myths of Symbolism and Social Relations in ancient Bactria and Margiana on its seals Mortuary and amulets.Pantographic Limited. Studies.Anglo-Saxon Cemeteries 1979.Eds P. Rahtz& L. [41] Sarianidi, V.I., (1998). Margiana and Watts.(British Archaeological Reports, Protozoroastrism.Athènes. 82.) Oxford, 143-160. 43 Basafa, H __________________________________ Intl. J. Humanities (2016) Vol. 23 (4): (30-46) [42] Sarianidi, V.I., DrevnostiStranyMargush. (1990): [49] Seyedsajadi, al., (2007). Reports Ashkhabad, SM of et ShahreSukhteh Ylym. 1.Vol 1. Department of Cultural Affairs of [43] Sarianidi, V., (1987). South-west Tehran. Asia: and [50] TahmasebiZaveh, H., (2015). Bactria Zoroastrians. International Association for Margiana Archaeological Complex in the Study of the Cultures of Central Asia, North East of Iran: native culture or Information Bulletin, 13, 44-56. cultural migrations, [44] the Sarianidi, Aryans V.I., (1984). influence. Proceedings of the National Conference of Archaeology in Raskopkimonumental’nÿkhzdaniina Birjand (Edited Dashlÿ-3. HashemiZarjAbadi). University of Birjand, DrevnyayaBaktriya. by Hassan MaterialÿSovetsko- Code 56. AfganskoiArkheologicheskoiÉkspeditsii, 5- [51] 32. inferences and mortuary practice. An [45] Saxe, A.,(1970). Dimensions of Tainter, J.,(1978). experiment Social in Social numerical classification.World Archaeology, 7: Mortuary Practice.University Microfilms, Ann 105-141. Arbor. [52] Trigger, B.,(1989). A History of [46] Soroush MR and Yousefi Archaeological H., (2014).Razeh site, a Witness to Third Thought.Cambridge:Cambridge Millennium to Historic Time Settlements University Press. in South Khorasan. Proceedings of the [53] Twelfth of Sistan.Vol Annual Meeting of Tuzi, M., (2006). Prehistory 5.Translated by Reza Archaeology. Tehran: Research Institute of Mehrafarin.Mashhad:Paj Publications. Cultural Heritage. [54] Vahdati, A.A., (2011). A Preliminary [47] Schmidt, E.F., (1933). TepeHissar Report on a Newly Discovered Petro Excavations glyphic Complex near Jorbat, the Plain of 1931.University Museum, University of Pennsylvania. Jajarm, Northeastern Iran. Paléorient, 177- [48] Seyedsajadi, S.M.,(2009). Collection 187. of Articles on ShahreSukhteh 1.Vol. 1, [55] Vahdati. A. A., (2014). A BAMC Central Grave Office of Cultural Heritage, from Bojnord, Handicraft and Tourism Organization of Iran.Iran LII.19-27. Sistan and Baluchistan, Zahedan. [56] Vahdati, A. North-Eastern and Bishuneh R.,(2014). Brief Report on the Second 44 Burial Cultures of Khorasan in Late Bronze Age __________ Intl. J. Humanities (2016) Vol. 23 (4) Season of Exploration in ChaloTepe in BC). Review of archeology of Khorasan, Jajarm Plain, Northeastern Iran. Reports of excerpts from archaeological finds and Thirteenth of cultural-historical treasures of Khorasan Archaeologists. Tehran: Research Institute (edited by MeysamLabafKhaniki). Public of Cultural Heritage. 320-324. Relations [57] Vahdati, A and Bishuneh R.,(2015). Cultural Affairs in collaboration with the The Third Chapter of Exploration in Department of Cultural Heritage, 37-47. TepeChalo, Jajarm Plain, northeastern [59] Iran. Reports Annual Frankfurt. (2010). Preliminary Report on Archaeologists. Tehran: speculation in DamghaniTepe in Sabzevar, Meeting Research Annual of of Meeting Fourteenth Institute of Cultural in Khorasan (3000-500 45 A, Magazine. 24 (P 48), 17-36. [58] Vahdati, A.,(2015). Bronze Age and Age Vahdati, Publishing Center Henri of Paul spring 2008. Archaeology and History Heritage. 529- 534. Iron and )Basafa, H __________________________________ Intl. J. Humanities (2016) Vol. 23 (4): (30-46 ﻓﺮهﻨﮓهﺎی ﺗﺪﻓﯿﻨﯽ ﺧﺮاﺳﺎن در ﻣﺮاﺣﻞ ﭘﺎﯾﺎﻧﯽ دوره ﻣﻔﺮغ ١ ﺣﺴﻦ ﺑﺎﺻﻔﺎ ﺗﺎرﯾﺦ ﭘﺬﯾﺮش١٣٩۶/٢/١۶ : ﺗﺎرﯾﺦ درﯾﺎﻓﺖ١٣٩۵/٣/٣ : ﭼﮑﯿﺪه ﻧﺤﻮۀ ﺧﺎﮐﺴﭙﺎری ﻣﺮدﮔﺎن از ﻣﻠﻤﻮسﺗﺮﯾﻦ ﻣﺪارک ﺟﻬﺖ ﺑﺎزﺳﺎزی و ﺷﻨﺎﺧﺖ ﻓﺮهﻨﮓ اﺟﺘﻤﺎﻋﺎت اﻧﺴﺎﻧﯽ ﻣﺤﺴﻮب ﺷﺪه ﮐﻪ دارای اﺑﻌﺎد ﻣﺎدی و ﻏﯿﺮﻣﺎدی اﺳﺖ .ﺑﺎ ﻣﻄﺎﻟﻌﮥ ﻣﺪارک ﻣﺎدی ﮐﺎوشهﺎی ﺑﺎﺳﺘﺎنﺷﻨﺎﺳﺎن ﺗﺎ ﺣﺪودی ﻣﯽﺗﻮان ﺑﻦﻣﺎﯾﻪهﺎی اﯾﺪﺋﻮﻟﻮژﯾﮏ را ﺗﻔﺴﯿﺮ ﮐﺮد .در اﯾﻦ زﻣﯿﻨﻪ ﺷﻨﺎﺧﺖ ﺷﯿﻮههﺎی ﺗﺪﻓﯿﻦ و ﺗﻔﺴﯿﺮ اﺷﯿﺎء درون ﮔﻮر ﺗﺒﻠﻮر ﻓﺮهﻨﮓ و ﺗﺼﻮرات ﻓﻠﺴﻔﯽ ﺑﺸﺮی ﻧﺴﺒﺖ ﺑﻪ ﺟﻬﺎن دﯾﮕﺮ ،آداب و رﺳﻮم ،ﺑﺎورهﺎی ﻣﺬهﺒﯽ و هﻤﭽﻨﯿﻦ ﺳﺎﺧﺘﺎرهﺎ و ﭘﯿﭽﯿﺪﮔﯽهﺎی اﺟﺘﻤﺎﻋﯽ اﺳﺖ .ﺣﻮزۀ ﻓﺮهﻨﮕﯽ ﺧﺮاﺳﺎن ﺑﺰرگ ﺑﻪﻋﻨﻮان ﯾﮏ هﺴﺘﻪ و ﻣﻨﻄﻘﮥ ﻓﺮهﻨﮕﯽ وﯾﮋه ﺑﺎ داﺷﺘﻦ اهﻤﯿﺖ اﺳﺘﺮاﺗﮋﯾﮏ )هﻤﺴﺎﯾﮕﯽ ﺑﺎ ﻣﻨﺎﻃﻖ ﻓﺮهﻨﮕﯽ ﻣﺘﻌﺪد ﺑﺎ ﻣﺤﻮرﯾﺖ ﺟﺎده ﺑﺎﺳﺘﺎﻧﻲ ﺧﺮاﺳﺎن ﺑﺰرگ( ﺑﺎ ﮐﻤﺒﻮد ﭘﮋوهﺶهﺎ در اﯾﻦ زﻣﯿﻨﻪ روﺑﻪرو اﺳﺖ هﺮ ﭼﻨﺪ ﮐﻪ در ﺳﺎلهﺎی اﺧﯿﺮ ﺑﺎ ﮐﺎوشهﺎی ﺑﺎﺳﺘﺎنﺷﻨﺎﺳﯽ اﻧﺠﺎمﺷﺪه ﻣﺪارک ﻣﺎدی وﯾﮋهای ﮐﺸﻒ ﺷﺪه اﺳﺖ .ﻧﻮﺷﺘﺎر ﺣﺎﺿﺮ ﺷﺎﻣﻞ دو ﺑﺨﺶ ﻣﻄﺎﻟﻌﮥ ﺳﺎﺧﺘﺎری ﺗﺪﻓﯿﻦهﺎ در ﻣﺮاﺣﻞ ﭘﺎﯾﺎﻧﯽ دورۀ ﻣﻔﺮغ ﺑﺎ روﯾﮑﺮد ﻣﻘﺎﯾﺴﻪ اﺳﺖ ﮐﻪ در ﻧﮕﺎه ﮐﻠﯽ ﺷﺎﻣﻞ ﺗﻬﯽ ﮔﻮر ،اوﻟﯿﻪ ،ﺛﺎﻧﻮﯾﻪ و ﻣﺸﺘﺮک اﻧﺴﺎﻧﯽ-ﺣﯿﻮاﻧﯽ ﻣﯽﺷﻮﻧﺪ و رﯾﺸﻪﺷﻨﺎﺳﯽ و ﻣﻨﺸﺎ ﻓﺮهﻨﮓهﺎی ﺗﺪﻓﯿﻨﯽ اﺳﺖ .ارزﯾﺎﺑﯽ ﻣﺪارک ﻧﺸﺎن از هﻤﮕﻮﻧﯽ ﺷﯿﻮههﺎی ﺗﺪﻓﯿﻦ ﺧﺮاﺳﺎن در دورۀ ﻣﻔﺮغ ﭘﺎﯾﺎﻧﯽ ﺑﺎ ﻓﺮهﻨﮓ ﭘﯿﺸﺮﻓﺘﮥ ﺑﻠﺨﯽ-ﻣﺮوی در آﺳﯿﺎی ﻣﯿﺎﻧﻪ دارد ﮐﻪ ﺣﻮزۀ ﭘﺮاﮐﻨﺶ آن ﻋﻼوه ﺑﺮ ﺧﺮاﺳﺎن در اﻓﻐﺎﻧﺴﺘﺎن ،ﭘﺎﮐﺴﺘﺎن ،ﺟﻨﻮب ﺷﺮق اﯾﺮان ،ﻗﻔﻘﺎز و ﻣﻨﺎﻃﻖ ﺟﻨﻮب ﺧﻠﯿﺞ ﻓﺎرس ﻣﺴﺘﻨﺪ ﺷﺪه اﺳﺖ. واژههﺎی ﮐﻠﯿﺪی :ﺧﺮاﺳﺎن ،دورۀ ﻣﻔﺮغ ﭘﺎﯾﺎﻧﯽ ،ﻓﺮهﻨﮓهﺎی ﺗﺪﻓﯿﻨﯽ ،آﺳﯿﺎی ﻣﯿﺎﻧﻪ ،ﻓﺮهﻨﮓ ﺑﻠﺨﯽ-ﻣﺮوی. .١ اﺳﺘﺎدﯾﺎر ﮔﺮوه ﺑﺎﺳﺘﺎنﺷﻨﺎﺳﯽ داﻧﺸﮕﺎه ﻧﯿﺸﺎﺑﻮر 46