International Journal of Hospitality Management 52 (2016) 24–32

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

International Journal of Hospitality Management

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijhosman

How is leadership related to employee self-concept?

Zhenpeng Luo a , Youcheng Wang b,∗ , Einar Marnburg c , Torvald Øgaard d

a

Institute of Tourism, Beijing Union University, Bei Si Huan Dong Lu No. 99, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100101, China

Rosen College of Hospitality Management, University of Central Florida, 9907 Universal Blvd, Orlando, FL 32819, USA

c

Faculty of Social Science, University of Stavanger, NO-4036 Stavanger, Norway

d

Norwegian School of Hotel Management, University of Stavanger, NO-4036 Stavanger, Norway

b

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 28 February 2014

Received in revised form 7 August 2015

Accepted 7 September 2015

Keywords:

Transformational leadership

Passive leadership

LMX

Self-concept

Hotel industry

China

a b s t r a c t

In the field of leadership research, the relationship between leadership styles and follower self-concept

was of great interests to researchers. The purpose of this study is to investigate how leadership styles

such as transformational leadership, passive leadership and leader-member exchange (LMX) relate to

employee self-concept. A total of 585 valid responses were collected from hotel front line employees in

mainland China. The results showed that the effect of transformational leadership on self-concept was

mainly mediated by LMX. The strong direct effects of LMX on levels of self-concept were also identified

in this study. Theoretical and practical implications were provided based on the results of this study.

© 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

The role of follower self-concept has attracted much research

attention in recent years (Hogg et al., 2003; Lord et al., 1999a,b; Lord

and Hall, 2005; van Knippenberg et al., 2004), and its mediating

role in the relationship between leadership and follower attitudes

and behaviors is also attracting the interests of researchers (Chang

and Johnson, 2010; van Knippenberg et al., 2004). Internal to subordinates, self-concept is a robust construct that reflects leader’s

influence on subordinate psychological, social, and cognitive outcomes (Lord and Brown, 2004). A key element to understanding

effective leadership is to understand follower self-concept (Lord

and Brown, 2004), which is important to shape employee behaviors, especially for services industry in which encounters between

employee and customer are crucial (Parasuraman et al., 1988). As

important as self-concept is to leadership, the theoretical integration of leadership and self-concept was constrained due to the

extensive scientific treatment of each of the topics even though

there were plethora of published papers on each topic (Lord and

Brown, 2004). Furthermore, empirical studies on self-concept relating to leadership processes were limited, and valuable theoretical

∗ Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses: lytzhenpeng@buu.edu.cn

(Z. Luo), youcheng.wang@ucf.edu (Y. Wang), einar.marnburg@uis.no (E. Marnburg),

torvald.ogaard@uis.no (T. Øgaard).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.09.003

0278-4319/© 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

and practical contributions to this field are still in demand (van

Knippenberg et al., 2004).

Limited research conducted on leadership and self-concept calls

for empirical studies examining the general as well as nuanced relationship between the two concepts for both theory advancement

and practical implementation. In the Chinese hotel industry, while

many well-known international brands are expanding their presence as part of their globalization strategy, the effectiveness and

appropriateness of their leadership styles substantiated mainly by

Western leadership theories have to be examined and adjusted in

this market. Furthermore, as hotel employees born after 1980s in

China are becoming the main workforce (62.7%) and are regarded

as more self-centered as a result of the single child family policy practiced in China for the last few decades (Su and Xiao,

2008), their self-concepts in the work environment will also be

an interesting topic for investigation. Therefore, the purpose of

this study was to empirically investigate the relationships between

leadership styles (i.e., transformational, passive leadership, and

leader-member exchange (LMX)) and employee self-concept in the

context of China’s hotel industry. More specifically, the objectives

intended to achieve in this study were: (1) to formulate the theoretical integration of leadership and self-concept; (2) to examine

how each of the three leadership styles is related to self-concept.

The findings of this study not only provide empirical evidences

on the relationships between leadership styles and subordinates’

self-concept, but also highlight the application and implication of

western theories in the context of Chinese hospitality industry, a

sector which is going through a fast paced globalization process.

Z. Luo et al. / International Journal of Hospitality Management 52 (2016) 24–32

2. Literature review

2.1. Self-concept

Self-concept is an overarching knowledge structure that helps

organize one’s goals and behavior. It can help individuals understand the self and others, and regulate social interactions based

on such an understanding (Lord and Brown, 2004). Putting it in a

managerial context, it affects the interactions between the control

of thoughts of executives and the resultant actions of subordinates.

Therefore, employee self-concept plays a very important role in our

understanding of the leadership concept.

Self-concept consists of three alternative levels (Brewer and

Gardner, 1996): the individual, relational, and collective. At the

individual level, one’s sense of uniqueness and self-worth are

derived from perceived similarities with and differences from other

individuals by interpersonal comparisons. At the relational level,

individuals define themselves in terms of dyadic connections and

role relationships with others, which may encourage cooperation

and/or shape behavior in relation to other individuals. The collective level involves self-definition based on one’s social group

memberships, where favorable inter-group comparisons give rise

to self-worth, which may motivate teamwork. Self-concept at different levels may cause different attitudes and varied behaviors

of subordinates; it reflects not only influences of leadership on

attitudes, but also behaviors of subordinates.

Alternatively, the three levels of self-concept can also be recategorized into two groups: the social self-concept consisting

of relational and collective self-concept, and the individual selfconcept which is more closely related to personal self-concept

(Lord and Brown, 2004). The former level of self-concept is more

favorable for leaders in service management since it stimulates

cooperation and teamwork, while the latter should be avoided

at work because it is self oriented and may cause unawareness

of the interests of customers or coworkers in service deliveries.

Therefore, how to influence employee’s self-concept is crucial in

effective leadership implementation in management contexts. In

the process of understanding how leadership can influence follower’s self-concept and behavior, working self-concept (WSC) is

crucial. WSC is the activated, contextual sensitive portion of selfconcept that can guide actions on the cues of one’s current context

and immediate past history (Lord and Brown, 2004).

2.2. Full range leadership theory (FRLT)

Full range leadership theory (FRLT) includes three types of leadership: transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire leadership

(Avolio and Bass, 2004). Transformational leadership includes five

factors: (1) idealized influence (attribute) (IIA), which refers to the

socialized charisma of the leader by which the leader is perceived

as being confident and powerful, focusing on higher-order ideals and ethics; (2) idealized influence (behavior) (IIB), which refers

to charismatic actions of the leader that embody values, beliefs,

and mission; (3) inspirational motivation (IM), which refers to the

ways in which leaders energize their followers with optimism,

ambitious goals, and idealized achievable vision; (4) intellectual

stimulation (IS), which refers to leader actions that appeal to followers’ sense of logic, challenge followers to think creatively and

find solutions to difficult problems; and, (5) individualized consideration (IC), which refers to leader behaviors that contribute

to follower satisfaction by advising, supporting, paying attention

to individual needs of followers, and developing followers by

allowing them to self-actualize. Transactional leadership comprises

the following three factors: (1) contingent reward (CR) leadership that refers to leader behaviors focusing on clarifying role

and task requirements and providing followers with material or

25

psychological rewards contingent on the fulfillment of contractual obligations; (2) management-by-exception active (MBEA) that

refers to the active vigilance to ensure that standards are met; and,

(3) management-by-exception passive (MBEP) in which leaders only

intervene after incidences occurred or when mistakes have already

been made. Laissez-faire leadership is generally considered the most

ineffective style of leadership because leaders avoid making decisions and taking responsibility with their authorities.

This study is based on leadership of hotel supervisors. Leadership styles are developed from the FRLT, which includes

transformational, transactional, and laissez faire leadership with

nine factors. According to a prior study (Luo et al., 2013), only two

factors of leadership styles were embodied by hotel supervisors in

China based on exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor

analysis with pretty good goodness-of-fit indices; they are renamed

as Transformational and Passive leadership. The new named Transformational leadership includes 12 items from IS, IM, IC of the original

transformational leadership scale, and CR of the original transactional leadership scale. II(A), II (B), and MBEA were excluded in

the new transformational leadership due to their low reliabilities,

and this result was also supported by prior studies (Hinkin and

Schriesheim, 2008; Yukl, 1999). It can also be argued that supervisors may lack the charismatic leadership compared to high level

leaders, and the MBEA behavior such as “Concentrates his/her full

attention on dealing with mistakes, complaints, and failures” may

not appropriate for supervisors due to Chinese culture such as

mian zi (face; maintaining the respect from others as well as to

respect others), ren qing (being kind or respecting the feeling of

others), and wan zhuan (indirect, non-confrontational expression)

(Shao and Webber, 2006). The new Passive leadership includes the

four items of MBEP of the original transactional leadership scale,

and the four items of Laissez-faire of FRLT (MLQ, Form 5X) (Avolio

and Bass, 2004). That is, in the context of hotel industry in China,

transactional leadership is not a unique factor, CR and MBEA fall

into the category of transformational leadership, and MBEP was

re-categorized as part of passive leadership. Similar findings were

supported by other researchers (Schriesheim et al., 2009; Tejeda

et al., 2001). As argued by Bycio et al. (1995), leaders are either

active to develop followers, form relationships of exchange, stimulate their thinking and inspire them to high level performance,

or they are passive or avoidant and only react to problems to be

corrected or do not react at all. Therefore, this two-factor model

of FRLT might not unique to Chinese supervisors, and investigation

and verification of this two factor model might be meaningful to not

only the globalized Chinese hotel industry, but also in some other

social and cultural contexts. Consequently, the two-factor construct

of FRLT was used as main leadership constructs in this study.

2.3. Leader-member exchange theory (LMX)

Leader-member exchange refers to the quality of the exchange

relationship that exists between employees and their superiors. It

describes the role-making processes between a leader and each

individual subordinate and the exchange relationship over time

(Yukl, 2005). It clearly incorporates an operationalization of a

relationship-based approach into leadership. LMX theory was formerly called the vertical dyad linkage (VDL) theory because its focus

is on reciprocal influence processes within vertical dyads between

one leader and his/her direct reporters. Therefore, LMX is also considered an important type of leadership for supervisors because

they interact with employees most frequently compared to higher

level leaders (Lord and Brown, 2004).

The essence of LMX is that effective leadership process is based

on the development of a mature leader–subordinate relationship, and they gain many benefits from the relationship (Graen

and Uhlbien, 1995). Therefore, LMX has tremendous impact on

26

Z. Luo et al. / International Journal of Hospitality Management 52 (2016) 24–32

employee in-role and extra-role performance, work attitudes such

as organizational commitment, and justice perceptions (Law et al.,

2000). However, its effects on employee self-concept need more

investigation in order to contribute to the understanding of the

relationship between LMX and employee self-concept.

2.4. Leadership and self-concept

While propositions that leadership may affect follower selfconcept, and self-concept mediates effects of leadership on

follower attitudes and behaviors were supported by previous

research (van Knippenberg et al., 2004), different aspects of leadership from different perspectives make the relationships complex

and introduce ambiguity on leadership theory. The three-domain of

leader, follower, and LMX leadership model can help us understand

and analyze leadership better (Graen and Uhlbien, 1995), address

each domain singularly. From this point of view, LMX is one type of

leadership between leaders and followers, and investigating how

Transformational, Passive, and LMX are related to self-concept will

contribute to understanding the effects of leadership more comprehensively. Lord and Brown (2004) believed that the three-level

depiction of self-concept is a very useful framework to understand how self-concept relates to leadership, and they proposed

that “leadership activities will be more effective when they are

matched to appropriate self-concept levels of subordinates” (Lord

and Brown, 2004, p. 53).

Transformational leaders are proactive. They raise followers’

awareness of collective interests, and help followers achieve

extraordinary goals. Bass (1985) suggested transformational leaders influence followers to transcend self-interest for the greater

good of their organizations in order to achieve optimal levels of performance, which may foster the collective-level self-concept (Lord

and Brown, 2004). It was also argued that some aspects of transformational leadership are associated with relational self-concept,

whereas others are associated with collective self-concept (Kark

and Shamir, 2002a,b; van Knippenberg and Hogg, 2003).

Graen and Uhlbien (1995) and Tse and Wing (2008) argued

that transformational leadership relates to LMX, and high-quality

leader–follower relationships (LMX) may lead followers to

incorporate organization–normative characteristics into their selfconception (i.e., relational and collective self-concept) (Engle and

Lord, 1997; van Knippenberg et al., 2004). Furthermore, just as

transformational leadership, LMX also helps foster collective selfconcept, and the combination of these two leadership can present

an alternative pathway to activating subordinate’s collective-selfconcept (Lord and Brown, 2004). Based on the above evaluations,

we propose the following relationships:

H1 . Transformational leadership is positively related to collective

self-concept.

H2 . LMX mediates the relationship between transformational leadership and collective self-concept.

Kark and Shamir (2002a,b) proposed that transformational

leadership behaviors may prime the relational self in personal identification with the leader or the collective self in social identification

with an organization. They also contend that this conceptualization links transformational leadership theory to dyadic models of

leadership (LMX). For instance, transformational leadership behaviors, such as individualized consideration that prime the relational

self, are likely to operate primarily at the dyadic level. Furthermore,

Lord and Brown (2004) and Lord et al. (1999a,b) propose that follower relational self-construal renders followers more sensitive to

the relational–interactional aspects of leadership. Therefore, LMX

is supposed to mediate the relationship between Transformational

or Passive leadership and Self-concept.

Investigation of the relationship between self-concept and LMX

suggested that follower interpersonal self-concept renders followers more sensitive to the relational aspects of leadership such as

LMX (Graen and Uhlbien, 1995). When interpersonal self-concept

is salient, many dyadic processes, such as LMX and mentoring are

likely to be more important in leadership (Lord and Brown, 2004).

However, it is unclear to what extent LMX relates to follower relational self-concept (van Knippenberg et al., 2004), and empirical

investigation of this issue would contribute to theory advancement

(van Knippenberg et al., 2004). We propose that:

H3 . LMX mediates the relationship between transformational leadership and relational self-concept.

H4 .

LMX is positively related to relational self-concept.

While a hierarchical person-centered type of leadership such as

transactional leadership may actively affect self-concept, LMX may

contribute to activating individual self-concept (Lord and Brown,

2004). That is, LMX may play an important role in the development

of Individual self-concept if the LMX quality is good. Furthermore,

Passive leadership was proved to be negatively related to effectiveness of leadership, employee satisfaction with leaders, and

employee extra role behavior (Luo et al., 2013), which may in

turn adversely drive Individual self-concept. Combining the forgoing

arguments, we propose that:

H5 . Passive leadership is positively related to Individual self-concept.

H6 . LMX mediates the relationship between Passive leadership and

individual self-concept.

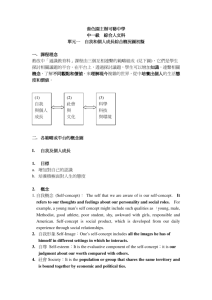

2.5. The conceptual model of the study

A conceptual model (see Fig. 1) was developed based on the

forgoing analysis and hypotheses, representing the causal relationships between the variables. Testing this model may extend

Collective

self -concept

Transformational

leadership

LMX

Relational

self -concept

Passive

leadership

Individual

self -concept

Fig. 1. The conceptual model of the study.

Z. Luo et al. / International Journal of Hospitality Management 52 (2016) 24–32

previous research in this area in several ways. First, this is the

first study to address the relationship between leadership and selfconcept, while most studies have focused on the direct effects of

leadership with self-concept being ignored. Second, Transformational, Passive leadership, and LMX were seldom studied together as

different leadership styles. It can be argued that their effects should

be differentiated when they are practiced in management. Third,

the results of this study have the potential of being generalized to

various management contexts in China thanks to its large sample

from a representative service segment of the hospitality industry.

3. Methods

3.1. Sampling and procedures

Building on an extensive literature review, particularly established measurement models tested in previous research in relation

to the constructs and variables examined in the study, a survey

questionnaire was created to serve as a data collection instrument

for the study. A pilot test of the questionnaire was conducted in a

hotel in Beijing for improvement before the survey was finalized.

For data collection, a total of 43 hotels were selected ranging

from three to five stars (24, 12, 8 hotels respectively), and the number in each category is roughly in proportion to the total number of

hotels in that category according to China National Tourism Administration classification (CNTA, 2013). Among which, the majority

(74%) are state-owned, followed by private or public-owned (12%),

and foreign or joint-venture properties (14%). Data from 23 hotels in

Beijing were collected by one of the researchers, with the assistance

of hotel managers. To avoid bias, confidential policy was declared

to the employees, and hotel managers were not allowed to administer the questionnaire filling process, nor were they granted access

to the finished questionnaires. The researcher collected the questionnaires in person in all instances. Data from the other 20 hotels

located in 12 provinces in China (3 in Shan Xi, 4 in Jinag Su, 1 in

Guang Xi, 1 in Si Chuan, 2 in Chong Qing, 1 in Liao Ning, 1 in Inner

Mongolia, 1 in He Nan, 2 in Gan Su, 1 in Hei Long Jiang, 1 in Shang

Dong, and 2 in Guang Dong) were collected and administered by

human resource managers of the hotels. Confidential policy was

also declared to the employees by HR managers, and respondents

were asked to seal the questionnaires with envelopes provided to

them, and the finished questionnaires were mailed to one of the

author by HR managers.

Although employees were selected using a convenience sampling method, in order to make the sample representative, every

three employees in each department of a hotel were selected to

participate in the survey. To achieve good inferential accuracy at a

95% confidence level and a 5% confidence interval, the sample size

was determined at a minimum of 385. Based on past experiences of

an average response rate of about 60% and a usable rate of around

80% for similar studies, a total of 1000 survey questionnaires were

distributed to the HR managers of each of the hotels for data collection. These managers were also sent a letter describing the nature

of the study, requesting their assistance and coordination in data

collection efforts. With the strong support of hotel managers, 640

responses were collected indicating a response rate of 64%, and 585

of which were valid, generating a 58.5% valid response rate.

A descriptive analysis of the employee demographic information shows that most of the respondents were from departments of

food & beverage (21.9%), housekeeping (20.6%), front office (19.2%),

facility & engineering (17.5%), and sales/marketing (14.3%). The

average age of respondents was 29 years old. Females accounted

for 60.8%, and male accounted for 39.2%. Most of the employees

obtained professional or high school education (45.6%), while 17.6%

of the employees had bachelor degrees and only 1.1% of them had

27

master degrees. The average monthly income of employees was

around US$220, ranking the lowest among varied industries based

on the latest statistics in China (National Bureau of Statistics of

China, 2011).

3.2. Measures

A 5-point Likert-type scale was used for all items in this study,

ranging from 1 = “Completely disagree” to 5 = “Completely agree”,

and the items were presented in Appendix A.

Self-concept was measured with Levels of Self-Concept Scale

(LSCS) (Johnson et al., 2006). The LSCS contains multiple subscales

for each of the three levels of self-concept. The three levels of selfconcept include: Individual self-concept (˛ = .73; example item: “I

feel best about myself when I perform better than others”); Relational self-concept (˛ = .79; example item: “I value friends who are

caring, empathic individuals”); and Collective self-concept (˛ = .82;

example item: “When I become involved in a group project, I do

my best to ensure its success”). Although this scale was used by

researchers (Chang and Johnson, 2010; Johnson et al., 2012), the

LSCS scale was also tested in the context of China’s hotel industry,

and the reliability and most of the validity indices of the LSCS were

acceptable (Marnburg and Luo, 2014). Therefore, the LSCS was used

in this study.

Transformational leadership (˛ = .90) was measured with 12

items from IM, IS, IC, and CR in MLQ (Form 5X) (Avolio and Bass,

2004). An example item was “Seeks differing perspectives when

solving problems”. Eight items were selected from MBEP and LF in

MLQ (Form 5X) (Avolio and Bass, 2004) to measure passive leadership (˛ = .81). One example item was “Avoid getting involved when

important issues arise”.

LMX was measured with 7 items developed by Graen and

Uhlbien (1995) (˛ = .85) which was widely used by researchers

(Boies and Howell, 2006; Michael et al., 2006). An example item

was “I know where I stand with my supervisor”. This study tests

the effect of LMX from the perspective of employees’ perceptions,

with no intention to measure difference or the congruence of LMX

between supervisors and employees. Therefore, we used subordinate LMX to measure supervisor–subordinate relationship.

3.3. Data analysis

Reliability tests were first conducted for internal consistency for

all the factors. Then correlation analysis was applied to examine

the inter-relationships between factors and the face validity of the

model that reflects the relationships among the factors (Hair et al.,

2011b). Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to test if

common method bias problem of the data occurred, and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to test the convergent and

discriminant validity of the variables. Structural equation modeling

analysis was conducted to further test how the model fits the data

using goodness-of-fit indices such as 2 , RMSEA, SRMR, AGFI, and

NNFI (Byrne, 1998; Hair et al., 2011a,b; Hu and Bentler, 1999). The

loadings of the paths in the structural model were used to test the

hypotheses.

4. Results

4.1. Correlations among factors

To explore the relationships between leadership and selfconcept, correlation analysis was conducted and the results were

reported in Table 1. The results showed that Transformational leadership and LMX were moderately related to Collective and Relational

self-concept, and weakly related to Individual self-concept. Passive

28

Z. Luo et al. / International Journal of Hospitality Management 52 (2016) 24–32

Table 1

Mean, standard deviation, and correlation coefficients between factors.

Factor

Mean

S.D.

1

2

3

4

5

6

1. Transformational

2. Passive leadership

3. LMX

4. Collective self-concept

5. Relational self-concept

6. Individual self-concept

3.66

1.76

3.81

4.36

4.22

3.25

.77

.69

.71

.58

.57

.78

(0.90)

−.50**

.67**

.45**

.42**

.13**

(0.8)

−.39**

−.23**

−.20**

.02

(0.85)

.44**

.49**

.21**

(0.8)

.65**

.25**

(0.7)

.31**

(0.73)

Note: ** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed); numbers in parentheses are reliability values Crobach’s alpha.

Table 2

Construct reliability, squared correlations between factors and AVEs of factors.

Factor

Construct reliability

1

2

3

4

5

6

1. Transformational leadership

2. Passive leadership

3. LMX

4. Collective self-concept

5. Relational self-concept

6. Individual self-concept

.90

.82

.85

.82

.80

.73

.44

.31

.58

.24

.20

.01

.37

.23

.09

.04

.01

.44

.27

.30

.04

.48

.62

.07

.45

.12

.36

Notes: 1. Values below the diagonal are squared correlation between factors. 2. Diagonal values are AVE values.

leadership had weak negative correlation with Collective and Relational self-concept, but was not significantly related to Individual

self-concept. In other words, while Transformational leadership and

LMX were main determinants of employee Collective and Relational self-concept, there were weak or insignificant relationships

between the three leadership styles and Individual self-concept.

An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to test if

common method bias problem of the data occurred. Sample size of

this study reached the ratio of 13 cases for each of the items (585/42

in this study). Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) has a value of .923, and

Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant at the 0.01 level. Therefore, the data was qualified to conduct exploratory factor analysis

(Hair et al., 2011a,b; Pallant, 2005).

Harman’s one-factor test was used to analyze the presence of

common method bias. All of the relevant items of the six factors

in the conceptual model of this study were put together to conduct the un-rotated factor analysis. If a single factor emerges or

one general factor explains most of the covariance in the independent and criterion variables, then substantial common method bias

is present (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Results showed that ten factors

were identified (Eigenvalues are greater than 1) with un-rotated

factor analysis, and a total variance of 64.81% was explained by

the ten factors, in which the largest total variance explained by

one factor being only 27.97%, representing no common method

bias.

We also conducted CFA to test the convergent validity and discriminant validity of the model. Goodness-of-fit indices are as follows: Chi-Square = 1887.53 (p = 0.0), df = 804; Chi-Square/df = 2.35;

RMSEA = 0.048; NNFI = 0.97; CFI = 0.97; Standardized RMR = 0.049;

GFI = 0.87; AGFI = 0.85, representing good fit to the data.

The construct reliabilities of the factors are consistent with

Cronbach’s alpha (see Table 2), representing good reliability of the

factors. With regard to convergent validity, only three items have

standardized loadings of less than 0.5 among the 42 items of the six

factors, indicating that these items are qualified to be in the model.

The AVE values of the six factors are less than 0.5 (see Table 2, the

rule of thumb is 0.5 or higher). Therefore, the convergent validity

of each factor is not ideal. On the other hand, not all the AVE values of the six factors are greater than the squared interconstruct

correlations associated with corresponding factors (see Table 2).

Therefore, the discriminant validity of the factors were not ideal

(Hair et al., 2011a,b).

The most significant observation is that Transformational leadership and LMX are correlated at .67 (Table 1). These two

constructs do not have adequate convergent and discriminant

validity (Table 2), and a multicollinearity problem may be present

(Grewal et al., 2004). Since the correlation is not too high (.67), the

measurements are not too poor, and the sample size quite substantial, the multicollinearity problems are deemed not too severe

(Grewal et al., 2004). The analysis results that include Transformational leadership and LMX simultaneously will however have to be

interpreted with some caution.

Although low convergent and discriminant validities of the factors were present from the above analyses, the factors of this study

were based on former studies. For instance, the significant difference between the concepts of Transformational leadership and

Passive leadership was identified by Luo et al. (2013). In detail, the

concepts of Transformational leadership and Passive leadership of

hotel supervisors in this study were derived from FRLT through

EFA analysis, and the results also show that a two-factor model

has better model fit indices than the traditional nine-factor model

from FRLT (Form 5X) (Avolio and Bass, 2004) based on CFA, and

good reliability and validity results. For the construct of LSCS, the

validity and reliability of it were also tested by Marnburg and Luo

(2014). Furthermore, LMX is a well developed measure, therefore,

these variables can be considered different from each other.

4.2. Test of the model and hypotheses

The relationships between the variables in the hypothesized

model was identified through correlation analysis (see Table 1), but

the causal relationships between them were examined using structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis with LISREL 8.80 program.

To test the hypothesized model, the assumptions of SEM analysis

such as sufficient sample size, outliers, multicollinearity, normality, and parameter identification were examined. Given sufficient

sample size for this study, normality, linearity, multicollinearity

were tested after checking outliers of the data. The Normal Probability Plot and Scattered Plot of standardized residuals were tested

to check the normality, linearity and independent of residuals of

the data (Pallant, 2005), and no violation of these assumptions

was identified. In addition, although two correlations were higher

(.67 for Transformational leadership and LMX and .65 for Eollective

self-concept and Relational self-concept) (Table 1), no serious multicollinearity was found in this study (Durbin–Watson statistic was

1.92, which was close to the expected value of 2, and VIF value was

less than 10) (Pallant, 2005). Therefore, assumptions of the analysis

are met.

Z. Luo et al. / International Journal of Hospitality Management 52 (2016) 24–32

Transformational

leadership

Collective

self-concept

ns

ns

0.74/13.56

LMX

ns

Passive

leadership

29

0.54/6.62

0.65/7.31

Relational

self-concept

0.36/5.73

Individual

self-concept

0.25/4.04

Fig. 2. The testing model of the study.

Table 3

Summary of SEM analysis and hypothesis test.

Path

Standardized estimate

t value

Result

TR → LMX

TR → CS

PL → IS

PL → LMX

LMX → CS

LMX → RS

LMX → IS

.73

.10

.25

−.06

.51

.60

.36

13.51

1.30

4.05

−1.34

6.36

10.26

5.69

Significant

H1 not supported

H5 supported

Not significant

Significant

H4 supported

Significant

Goodness-of-fit statistics: 2 (811, n = 585) = 1988.66, p = .00; RMSEA = 0.05;

CFI = 0.95; SRMR = 0.07; GFI = 0.88; AGFI = 0.87; Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI) = 0.96.

Note: TR = transformational leadership; PL = passive leadership; CS = collective selfconcept; RS = relational l self-concept; IS = individual self-concept.

Results showed that the goodness-of-fit indices for the model

were as follows: 2 = 1988.66; p < .001; CFI = 0.95; SRMR = .07;

RMSEA = .05; GFI = .88; AGFI = .87; NNFI = 0.96. The specified paths

from leadership styles to self-concept in the model presented a

good fit to the data (Byrne, 1998). In reviewing the structural

parameter estimates for the model, two of them were found not

significant: the path from Transformational leadership to Collective

self-concept, and the path from Passive leadership to LMX (t values were 1.30 and −1.34 respectively, representing insignificant

relationships) (Byrne, 1998). The other parameter estimates in the

model were significant, and a final model was built with these two

paths deleted from the original model (see Fig. 2).

For the six hypotheses, statistics showed that H1 was not

supported ( = .10; t = 1.30), which means that Transformational

leadership was not directly related to Collective self-concept. H4 was

supported (ˇ = .60; t = 10.25), indicating that LMX was related to

Relational self-concept. Passive leadership was directly related to

Individual self-concept (ˇ = .25; t = 4.05), thus H5 was supported (see

Table 3).

With regard to the mediating role of LMX, three hypotheses

were involved: H2 , H3 , and H6 . As depicted in Fig. 2, several observations can be made. First, it is noticeable that LMX was significantly

related to collective self-concept (ˇ = .51; t = 6.36) and relational selfconcept (ˇ = .60; t = 5.69). Second, Transformational leadership was

strongly related to LMX ( = .73; t = 13.51), but was not directly

related to Collective self-concept, which was supported by the test

results of H1 and H2 . As a result, the hypothesized mediating role

of LMX between Transformational leadership and Collective selfconcept was supported. Third, Passive leadership was not related to

LMX (ˇ = −.06; t = −1.34), therefore, the hypothesis (H6 ) that LMX

mediates the relationship between Passive leadership and Individual self-concept was not supported. However, Passive leadership was

weakly related to Individual self-concept (standardized loading was

.25).

Regarding to H3 , significant relationships between Transformational leadership and LMX (.74), and between LMX and Relational

self-concept (.65) were identified, which implied potential mediated relationships among Transformational leadership, LMX, and

Relational self-concept. To test the direct effect of Transformational leadership in the original model, the revised model with the

path from Transformational leadership to Relational self-concept was

assessed by SEM analysis to see if the model fit was substantially

changed (2 ) compared to the original one.

Results of SEM analysis on the revised model showed a 2 = .33

(2151.99–2151.66) with one degree of freedom (p = .00), which is

not a significant change. There was no change in RMSEA (.05),

which indicates no significant direct effect of Transformational leadership on Relational self-concept (Hair et al., 2011a,b). Furthermore,

the relationship between Transformational leadership and Relational

self-concept in the revised model was not significant ( = −.07;

t = −.99), while the paths from Transformational leadership to LMX,

and the path from LMX to Relational self-concept were still significant (see Fig. 2 with path coefficients and associated t values).

Therefore, H3 was supported which indicates that the relationship

between Transformational leadership and Relational self-concept was

fully mediated by LMX, and LMX is indispensable in the relationship.

The final results of this study show that the full mediating role of LMX on the relationship between Transformational

leadership and self-concept at different levels is salient, while

there is no mediating effect of LMX on the relationship between

Passive leadership and individual self-concept. The direct effect

of Passive leadership on individual self-concept is weak in the

model (0.25). Though it is not significant in terms of correlation, it has significant but weak correlations with collective and

interpersonal self-concept. Therefore, the direct effect of Passive

leadership on self-concept can be neglected. However, there might

be some indirect effect or moderating role of Passive leadership on

self-concept.

By integrating the above results of this study, it can be summarized that the effect of Transformational leadership on self-concept

was fully mediated by LMX, while the effects of

Passive leadership on self-concept were not supported, and the

strong direct effects of LMX on Collective self-concept and Relational

self-concep were identified in this study.

5. Conclusions

Empirical studies on self-concept were limited (van

Knippenberg and Hogg, 2003). This study not only empirically

investigated the antecedents of self-concept from the perspective of leadership, but also contextualized the investigation in a

30

Z. Luo et al. / International Journal of Hospitality Management 52 (2016) 24–32

different cultural context - the Chinese culture. More specifically,

this study investigated the relations between leadership behaviors

and subordinates’ self-concept at the supervisor level in the hospitality industry. Findings of this study provided valuable evidence

for applications of Western theories as well as the associated

managerial implications in China’s hospitality industry.

In this study, the relationship between leadership and subordinates’ self-concept was investigated. In particular, the relationships

among Transformational, Passive leadership, LMX and self-concept

were tested based on six hypotheses in the model. Results showed

that two of the hypotheses (H1 and H6 ) were not supported and

four of them were supported. In summary, we found that first,

there was no direct effect of Transformational leadership on Collective and Interpersonal self-concept, but the relationships between

Transformational leadership and the two levels of self-concept were

mediated by LMX. Second, there were significant relationships

between LMX and the three levels of self-concept, in which the relationship between LMX and Relational self-concept was the strongest

(0.65), while the relationship between LMX and Individual selfconcept was the weakest (.36) among the three relationships. Third,

the impact of Passive leadership on Individual self-concept was weak

(.25), and it was not mediated by LMX in the model. Based on the

above findings of this study, the following theoretical contributions

and practical implications can be drawn.

5.1. Theoretical contributions

The finding that Transformational leadership was strongly related

to collective self-concept was consistent with Lord et al. (1999a,b)’s

argument that transformational leadership fits better with Collective self-concept. While not directly related, they were mediated

by LMX according to the results of this study. This means that the

nature of leader-member exchange will affect or guide individuals

toward either collective- or Individual-level self-concept (Lord et al.,

1999a,b). Therefore, we identified a causal relationship from Transformational leadership to LMX, and to Collective self-concept, which

is a new finding compared to prior studies.

LMX is indeed important in guiding behavior and attitudes

when self-concept is defined at a relational level (Lord et al.,

1999a,b). High level LMX can develop Collective self-concept, which

was supported by the strong positive relationships between LMX

and relational and Collective self-concept. The weak significant relationship between LMX and Individual self-concept indicated that

low-quality supervisor–subordinate relationship may end in individual or self-oriented self-concept.

In addition to the effect of transformational leadership, the findings of this study also provided insights in understanding the effects

of Passive leadership (Laissez-faire leadership and MBEP) on selfconcept, which was normally ignored in leadership studies. For

Passive leadership, its positive and significant main effect on Individual self-concept was identified, while its effect on LMX was not

significant. Passive leadership does not contribute to either collective self-concept or relational concept. These findings provided new

insights on the effects of Passive leadership (Laissez-faire leadership

and MBEP) that were ignored by researchers.

5.2. Practical implications

For supervisors in the hotel industry, it is crucial for them to

motivate frontline employees in their encounters with guests. Since

their self-concept can drive their behaviors, therefore, supervisors

should focus on the development of employee self-concept, especially the collective level self-concept that drives teamwork and

organizational achievement. To this end, supervisors should exercise their leadership through good relationship with employees in

terms of work related relationship as well as non-work relationship

rooted in Chinese culture (Littrell, 2002), with the latter demonstrating a strong direct and mediating effect of Transformational

leadership on employee self-concept.

It is also recommended that supervisors put more effort on

their behaviors that embody transformational leadership, since

supervisors at Chinese hotels appear to be weak in IIA and IIB of

transformational leadership in MLQ (Form 5X) (Luo et al., 2013).

We also suggest supervisors to develop related behaviors of IIA and

IIB that can be learned, which are important to develop collective

self-concept at organizational or group level (Shamir et al., 1993,

Shamir, House, and Arthur, 1993). Other transformational leadership behaviors, such as individualized consideration that prime the

relational self-concept in personal identification with the leader

should also be employed at work to achieve expected outcomes

(Kark and Shamir, 2002a,b).

5.3. Limitations and directions for future research

Like other studies, this study also has some limitations. First, the

study was conducted in the hospitality industry in the context of

Eastern culture. A comparative examination of the model in Western culture will contribute more to our understanding of the impact

of cultural differences on leadership related issues (Hofstede and

Hofstede, 2005). Second, the questionnaires were self-reported by

employees, which may introduce bias to the results even though the

survey was well administered by the research team. As a result, caution is required in generalizing the findings of this study to practical

applications. Third, to better understand the leadership effects, surveys on higher level leaders such as department managers or higher

should also be conducted. Fourth, although effects of Transformational and Passive leadership for hotel supervisors were discussed in

this study, effects of Transactional leadership for higher level leadership deserve more attention in future studies. Finally, we have

to acknowledge that the convergent and discriminant validities of

the constructs in the model of this study were not ideal. Since the

problem may be caused by the high correlation between Transformational leadership and LMX, or the low convergent validity of

LSCS, results should be interpreted with caution, and improvement

of the validities of these constructs should be sought after in future

studies.

Appendix A. Construct measures

Transformational leadership

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

Provides me with assistance in exchange for my efforts (CR)

Seeks differing perspectives when solving problems (IS)

Talks optimistically about the future (IM)

Discusses in specific terms who is responsible for achieving

performance targets (CR)

Spends time teaching and coaching (IC)

Treats me as an individual rather than just as a member of a

group (IC)

Articulates a compelling vision of the future (IM)

Gets me to look at problems from many different angles (IS)

Helps me to develop my strengths (IC)

Suggests new ways of looking at how to complete assignments

(IS)

Expresses satisfaction when I meet expectations (CR)

Expresses confidence that goals will be achieved (IM)

Passive leadership

1. Re-examines critical assumptions to question whether they are

appropriate (MBEP)

2. Avoid getting involved when important issues arise (LF)

Z. Luo et al. / International Journal of Hospitality Management 52 (2016) 24–32

3. Is absent when needed (LF)

4. Waits for thing go wrong before taking action (MBEP)

5. Shows that he/she is a firm believer in “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix

it” (MBEP)

6. Demonstrates that problems must become chronic before taking

action (MBEP)

7. Avoids making decisions (LF)

8. Delays responding to urgent questions (LF)

LMX

My supervisor understands my job-related problems and needs.

I know where I stand with my supervisor.

My supervisor recognizes my potential.

My supervisor would use his/her power to help me solve work

related problems.

5. My supervisor would “bail me out” at his/her expense.

6. I defend and justify my supervisor’s decisions when he/she is not

present to do so.

7. I have an effective working relationship with my supervisor.

1.

2.

3.

4.

Individual self-concept

1 I thrive on opportunities to demonstrate that my abilities or talents are better than those of other people.

2 I have a strong need to know how I stand in comparison to my

coworkers.

3 I often compete with my friends.

4 I feel best about myself when I perform better than others.

5 I often find myself pondering over the ways that I am better or

worse off than other people around me.

Interpersonal self-concept

1. If a friend was having a personal problem, I would help him/her

even if it meant sacrificing my time or money.

2. I value friends who are caring, empathic individuals.

3. It is important to me that I uphold my commitments to significant people in my life.

4. Caring deeply about another person such as a close friend or

relative is important to me.

5. Knowing that a close other acknowledges and values the role

that I play in their life makes me feel like a worthwhile person.

Collective self-concept

1. Making a lasting contribution to groups that I belong to, such as

my work organization, is very important to me.

2. When I become involved in a group project, I do my best to ensure

its success.

3. I feel great pride when my team or group does well, even if I’m

not the main reason for its success.

4. I would be honored if I were chosen by an organization or club

that I belong to, to represent them at a conference or meeting.

5. When I’m part of a team, I am concerned about the group as a

whole instead of whether individual team members like me or

whether I like them.

References

Avolio, Bass, Retrieved April 30 2007, from Mind Garden Inc. 2004. Multifactor

Leadership Questionnaire.

Bass, B.M., 1985. Leadership and Performance Beyond Expectation. Free Press, New

York.

Boies, K., Howell, J.A., 2006. Leader–member exchange in teams: an examination of

the interaction between relationship differentiation and mean LMX in

explaining team-level outcomes. Leadersh. Q. 17 (3), 246–257.

Brewer, M.B., Gardner, W., 1996. Who is this “we”? Levels of collective identity and

self representations. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 71, 83–93.

31

Bycio, R., Hackett, R.D., Allen, J.S., 1995. Further assessments of Bass’

conceptulization of transactional and transformational leadership. J. Appl.

Psychol. 80, 468–478.

Byrne, B.M., 1998. Structural equation modeling with LISREL, PRELIS, and SIMPLIS:

basic concepts, applications, and programming. L. Erlbaum Associates,

Mahwah, NJ.

Chang, C.-H.D., Johnson, R.E., 2010. Not all leader–member exchanges are created

equal: importance of leader relational identity. Leadersh. Q. 21, 796–808.

CNTA, 2013. China Tourism Industrial Statistics Annual Report 2013–2014. http://

www.cnta.gov.cn/html/2014-9/2014-9-24-%7B@hur%7D-47-90095.html.

Engle, E.M., Lord, R.G., 1997. Implicit theories, self-schemas, and leader-member

exchange. Acad. Manag. J. 40 (4), 988–1010.

Graen, G.B., Uhlbien, M., 1995. Relationship-based approach to leadership –

development of leader-member exchange (Lmx) theory of leadership over 25

years – applying a multilevel multidomain perspective. Leadersh. Q. 6 (2),

219–247.

Grewal, R., Cote, J.A., Baumgartner, H., 2004. Multicollinearity and measurement

error in structural equation models: implications for theory testing. Mark. Sci.

23 (4), 519–529.

Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J., Abderson, R.E., 2011a. Multivariate Data Analysis,

7th ed. China Machine Press, Beijing.

Hair, J.F., William, B.C., Babin, B.J., Anderson, R.E., 2011b. Multivariate Data

Analysis, 7th ed. Beijing, China Machine Press.

Hinkin, T.R., Schriesheim, C.A., 2008. A theoretical and empirical examination of

the transactional and non-leadership dimensions of the Multifactor Leadership

Questionnaire (MLQ). Leadersh. Q. 19 (5), 501–513.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G.J., 2005. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the

Mind. McGraw-Hill, New York.

. Hogg, M.A., Knippenberg, D.V. (Eds.), 2003. Social Identity and Leadership

Processes in Groups, 35. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

Hu, L., Bentler, P.M., 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure

analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Eq. Model. 6,

1–55.

Johnson, R.E., Veuns, M., Lanaj, K., Mao, C., 2012. The leader identity as an

antecedent as the frequency and consistency of transformational,

consideration, and abusive leadership behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 97 (6),

1262–1272.

Kark, R., Shamir, B., 2002a. The dual effect of transformational leadership: priming

relational and collective selves and further effects on followers. In: Avolio,

J.Y.F.J. (Ed.), Transformational and Charismatic Leadership: The Road Ahead,

vol. 2. JAI Press, Amsterdam, pp. 67–91.

Kark, R., Shamir, B. (Eds.), 2002b. Academy of Management Proceedings, vol. 2002.

Academy of Management.

Law, K.S., Wong, C.-S., Wang, D., Wang, L., 2000. Effect of supervisor–subordinate

guanxi on supervisory decisions in China: an empirical investigation. Int. J.

Hum. Resourc. Manag. 11 (4), 751–765.

Littrell, R.F., 2002. Desirable leadership behaviours of multi-cultural managers in

China. J. Manag. Dev. 21 (1), 5–74.

Lord, R.G., Brown, D.G., 2004. Leadership Process and Follower Self-identity.

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., Publishers, Mahwah, NJ.

Lord, R.G., Brown, D.J., Freiberg, S.J., 1999a. Understanding the dynamics of

leadership: the role of follower self-concepts in the leader/follower

relationship. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 78, 1–37.

Lord, R.G., Brown, D.J., Freiberg, S.J., 1999b. Understanding the dynamics of

leadership: the role of follower self-concepts in the leader/follower

relationship. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 78 (3), 167–203.

Lord, R.G., Hall, R.J., 2005. Identity, deep structure and the development of

leadership skill. Leadersh. Q. 16 (4), 591–615.

Luo, Z., Wang, Y., Marnburg, E., 2013. Testing the structure and effects of full range

leadership theory in the context of China’s hotel industry. J. Hosp. Mark.

Manag. 22 (6), 656–677.

Marnburg, E., Luo, Z., 2014. Testing the validity and reliability of the levels of

self-concept scale in the hospitality industry. J. Tour. Recreat. 1 (1),

37–50.

Michael, J.H., Guo, Z.G., Wiedenbeck, J.K., Ray, C.D., 2006. Production supervisor

impacts on subordinates’ safety outcomes: an investigation of leader-member

exchange and safety communication. J. Saf. Res. 37 (5), 469–477.

National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2011. Average Wage of Employed Persons in

Urban Units by Sector in Detail (2010) [Electronic Version], Retrieved http://

www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2011/indexch.htm.

Pallant, J., 2005. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using

SPSS for Windows (Version 12). Open University Press, Maidenhead.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithmal, V.A., Berry, L.L., 1988. SERVQUAL: A Multiple-Item Scale

for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J. Retail. 64 (1).

Podsakoff, P.M., MacKenzie, S.B., Lee, J.Y., 2003. Common method biases in

behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended

remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88 (5), 879–903.

Schriesheim, C.A., Wu, J.B., Scandura, T.A., 2009. A meso measure? Examination of

the levels of analysis of the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ).

Leadersh. Q.

Shamir, B., House, R.J., Arthur, M.B., 1993. The Motivational Effects of Charismatic

Leadership: A Self-Concept Based Theory, vol. 4., pp. 577–594.

Shao, L., Webber, S., 2006. A cross-cultural test of the ‘five-factor model of

personality and transformational leadership’. J. Bus. Res. 59 (8), 936–944.

Su, H., Xiao, K., 2008. An analysis on characteristics and management of employees

born after 1908’s contemporary. Young Res. 4, 54–58.

32

Z. Luo et al. / International Journal of Hospitality Management 52 (2016) 24–32

Tejeda, M.J., Scandura, T.A., Pillai, R., 2001. The MLQ revisited – psychometric

properties and recommendations. Leadersh. Q. 12 (1), 31–52.

Tse, H.H.M., Wing, L.A.M., 2008. Transformational leadership and turnover: the

roles of LMX and organizational commitment. Acad. Manag. Annu. Meet. Proc.,

1–6.

van Knippenberg, D., Hogg, M.A., 2003. A social identity model of leadership

effectiveness in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, vol. 25.,

pp. 243–295.

van Knippenberg, D., van Knippenberg, B., De Cremer, D., Hogg, M.A., 2004.

Leadership, self, and identity: a review and research agenda. Leadersh. Q. 15

(6), 825–856.

Yukl., 1999. An evaluation of conceptual weaknesses in transformational and

charismatic leadership theories. Leadersh. Q. 10 (2), 285–305.

Yukl., 2005. Leadership in Organizations, 6th ed. Pearson/Prentice Hall, Upper

Saddle River, NJ.