EMvG 18.07.30 Thesis

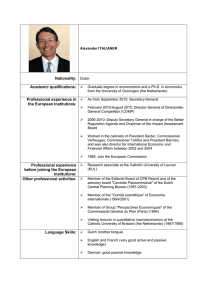

advertisement