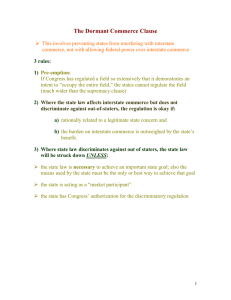

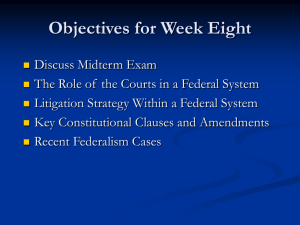

Constitutional Law Outline

advertisement