Dr. David Cababaro Bueno Teaching Perfromance of Graduate School Faculty CC The Journal Vol. 13 Oct. 2017 ISSN 1655-3713

advertisement

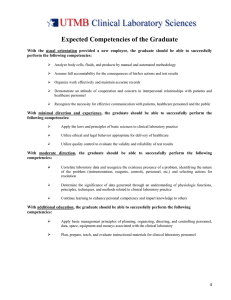

CC The Journal Vol. 13 Oct. 2017 Teaching Perfromance of Graduate School Faculty as Input to Professional Development Dr. David Cababaro Bueno ============================================== Abstract- The present study determines the training needs of graduate faculty based on the Expected Performance Standards (EPS) set by one of the Private Higher Education Institutions (PHEIs) in the Philippines and to propose a professional development (PD) program. The descriptive statistical analysis was used to show the training needs of the faculty. The teaching outcomes were based on the average performance assessments conducted by the Dean among the graduate school faculty. The results showed that graduate school faculty members were outstanding in achieving the objectives of the graduate program by showing mastery of subject matter, relating current issues and community needs and participating to the activities of professional organizations. However, they were just satisfactory in demonstrating mastery of research skills relative to their own research output, assisting graduate students in developing research competencies, and showing professional growth through research activities and publications. It is undeniably essential to include in the PD the need to continually upgrade their research preparation, dissemination and utilization. Keywords: Education, teaching outcomes, graduate school faculty, professional development, descriptive design Introduction Professional development cannot succeed without strong content. The content of the professional development that is associated with highperforming schools is always focused and serves a well-planned long-term strategy. To be effective, professional development should be based on curricular and instructional strategies that have a high probability of affecting student learning—and, just as important, students’ ability to learn. In addition, professional development should (1) deepen teachers’ knowledge of the subjects being taught; (2) sharpen teaching skills in the classroom; (3) keep up with developments in the individual fields, and in education generally; (4) generate and contribute new knowledge to the profession; and (5) increase the ability to monitor students’ work, in order to provide constructive feedback to students and curricular and instructional strategies that have appropriately redirect teaching (Harwell, 2003). Higher education has undergone a great deal of change in the last century, especially during the last 50 years. Although there has been 1 CC The Journal Vol. 13 Oct. 2017 tremendous growth and pedagogical advances, the last decade has witnessed serious attacks on the academy, as well as on the faculty and students within higher education (Heppner & Johnson, 1994). It seems that new challenges face the academy and widespread changes affect virtually all aspects of higher education today. According to Millis (1994), complex changes that universities respond to includes expectations about the quality of education, changing technology and its impacts on teaching and learning, nature and value of assessment, the academy’s continuing ability to meet the changing and developing needs of the society effectively, diverse compositions of students populations, changing paradigms in teaching and learning, colleges and universities, for whatever reasons, have been neither sufficiently alert to the ever-changing circumstances of their instructional staffs nor adequately resourceful in meeting their changing needs for professional development. It is indeed striking how much has been written about faculty growth and renewal and how few campuses have seen fit to develop comprehensive, systematic programs (Schuster, 1990). In order to achieve an effective educational reform, faculty development emerged is an important factor. In general, faculty development facilitates the professional, personal, organizational and instructional growth of faculty and faculty members. It promotes improvement in the academy in large part through helping individuals to evolve, unfold, mature, grow, cultivate, produce, and otherwise develop themselves as individuals and as contributors to the academy’s mission (Watson & Grossman, 1994). The primary goals of higher education institutions in the Philippines are enhancing and maintaining academic excellence. Faculty members are the most important factor for achieving these goals since they are responsible for implementing the tasks that are directly associated with the goals. Therefore, graduate school needs effective faculty members to enhance necessary skills and enable them to work more effectively (Prachyapruit, 2001). Faculty development can play a significant role in increasing the quality of a faculty environment, particularly by emphasizing academicians’ roles as instructors. Faculty development has been an integral part of higher education for many years. In the decades proceeding the 1970s faculty development programs in universities and colleges in the Philippines were similar to inservice programs in K to 12 schools based on scope and direction. In the mid 1970s, however, faculty development went through a major metamorphosis from context and process based programs to programs designed to develop 2 CC The Journal Vol. 13 Oct. 2017 faculty members as teachers and facilitators of learning (Chun, 1999; Millis, 1994). In Philippines, the quality of higher education institutions has been an important issue for several years. Following the emergence of new private universities in the last few years, a challenge among private and public educational institutes has begun in attracting students to themselves. It seems that all of the public and private universities are facing increasingly new demands to improve the quality in their educational missions. In spite of having brilliant history of quality of education among HEIs in the Philippines, the College did not institutionalize a clear campus-wide program for training faculty members or other activities based on a faculty development program until the year 2013. Since then some unlimited activities, such as seminars for faculty and trainings for those researchers who came temporarily from other universities have been done. Thus, there were few professional preparatory programs are offered to graduate students to provide them with necessary teaching skills or techniques. In general, knowing the content of the subject does not guarantee an effective teaching, similar to other colleges and universities, suffers from welldesigned faculty development programs. Today, teachers are expected to develop complex skills, such as research skills, in their students while implementing new views on learning and teaching and using authentic assessment strategies. About these new assessment strategies there is much debate and teachers are vulnerable in using them. Researchers (Stokking, van der Schaaf, Jaspers, & Erkens, 2004) have studied upper secondary education natural and social science teachers' practices using two surveys and two rounds of expert panel judgment on teachersubmitted assessment-related material and information. They emphasized a common concern on research skills regarding the clarity of teachers' assessment criteria, the consistency between teachers' goals, assignments, and criteria, and the validity and acceptability of teachers' assessment practices. Moreover, the Professional and Organizational Development Network in Higher Education (POD, 2003) emphasized that faculty development generally focused on the individual faculty member. It should provide consultation on teaching, including class organization, evaluation of students, in-class presentation skills, questioning and all aspects of design and presentation. They also advised faculty on other aspects of teacher/student interaction, such as advising, tutoring, discipline policies and administration. Another focus of such program is the faculty member as a scholar and professional. It should offer assistance in career planning, professional development in scholarly skills such 3 CC The Journal Vol. 13 Oct. 2017 as grant writing, publishing, committee work, administrative work, supervisory skills, and a wide range of other activities expected of faculty. Thus, professional development should be designed around research-documented practices that enable educators to develop the skills necessary to implement what they are learning. Thus, there is a need for college administrators to initialize faculty development activities solely for graduate school faculty. Thus, this research was designed to bridge the gap previously presented in conducting training needs analysis and its practical delivery in Continuing Professional Education activities and programs intended for graduate faculty in a private college focused on other dimensions such as professional performance, instructional procedures and techniques, and evaluation and grading. Components of Faculty Development in Higher Education Institutions There is a need for faculty across all disciplines to understand best instructional practices and the strategies that develop effective teaching behaviors and skills. While faculty members at the university level are considered experts in their field of study, many may not have been trained in practices of effective teaching, how to share their expertise, or how to improve their teaching. The induction and mentoring of faculty members is often overlooked in higher education, but many faculty members report they struggle with the teaching aspects of their responsibilities. Creation and evaluation of a faculty development program can aid in the formation of best instructional practices and increase the competency of faculty in meeting the challenges of educating students. Brookes (2010) suggests that a blend of online and face-toface meetings could be used to provide programs to support faculty. Helping faculty to understand who they are as teachers and instilling a belief that they can be successful teachers are integral aspects of faculty development. By designing and evaluating a new faculty development program, we hope to gain a better understanding of the impact of development programs on faculty competencies and student outcomes (Rowbotham, 2015). The functions of the faculty can be defined in four overlapping tasks as follows (Bowen & Schuster, 1986): (1) Instruction. The main function of faculties is instruction, that is, direct teaching of students. Instruction involves formal teaching of groups of students in classrooms, laboratories, studios, gymnasia, and field settings. It also involves conferences, tutorials, and laboratory apprenticeships for students individually. Instruction also entails advising students on matters pertaining to 4 CC The Journal Vol. 13 Oct. 2017 their current educational programs, plans for advanced study, choice of career, and sometime more personal matters. (2) Research. Faculties contribute to the quality and productivity of society not only through their influence on students but also directly through the ramified endeavors called as research. This term is used as shorthand for all the activities of faculties that advance knowledge and the arts. The activities may be classed as research if they involve the discovery of new knowledge or the creation of original art and if they result in dissemination usually by means of some form of durable publication. (3) Public service. Public services can be performed by faculties in connection with their teaching and research. The most notable is teaching delivered by faculty in university. Faculties are also engaged in activities designed specifically to serve the public, usually in an educational and consulting capacity. Perhaps the most important public service function of faculties is that they serve as a large pool of diversified and specialized talent available on call for consultation and technical services to meet an infinite variety of needs and problems. (4) Institutional governance and operation. Faculties, individually and collectively, usually occupy a prominent role in the policies, decisions, and ongoing activities falling within the wide-ranging realm of institutional governance and operation. Faculty members contribute enormously to institutional success through their efforts to create and sustain a rich cultural, intellectual, and recreational environment in the campus. Moreover, as it can be seen the work of faculty members is extraordinarily important to the economic and cultural development of the nation. If the quality of the system and its people deteriorate, it will be less able to provide the teaching, research, and public service activities. According to Chism, Lees and Evenbeck (2002), the basic model of teaching changed from teaching as transmission of content to teaching as the facilitation of learning. Thus, Wilkerson and Irby (1998) stated that TNA is a tool for improving the educational vitality of academic institutions through attention to the competencies needed by individual teachers, and to the institutional policies required to promote academic excellence. Training Needs Assessment Training Needs Analysis (TNA) is the key to reshaping the future of Continuing Professional Development (CPD) Program in the educational 5 CC The Journal Vol. 13 Oct. 2017 system. It is the major component of training programs. It is a crucial component of learning for ascertaining both the needs of the learners and the organization and as such it provides a fundamental link with relevant and effective teaching and learning process. Harris (1980) defined training in the field of education as a planned program which consists of learning opportunities offered to faculty members in the educational institution in order to improve their performance in their specific work. Thus, it as a regulator and as a planned voltage to provide manpower in the organization of certain knowledge, improving and developing their skills and capabilities, and changing its behavior and trends positively, while Al-Sakarneh (2011) defined it as a planned activity designed to bring about changes in the individual and in the community in terms of information and experiences, skills, levels of performance, ways of working, and behavior and trends. Thus, this makes individual or group to be effective in doing their jobs in high production efficiency. To meet the educational needs of the new global organization, lecturers need continuing professional development in order to maintain and upgrade their skills. They also need to exemplify a willingness to explore and discover new technological capabilities that would enhance and expand learning experiences. Several studies have been conducted relative to professional development focusing on ICT skills (Akinnagbe, 2011), pedagogical competencies, management and assessment competencies and research competencies among teachers and lecturers (Fakhra & Mahar, 2014). For Akinnagbe, it is absolutely essential that lecturers should improve their ICT skills properly. They need a wide variety of educational opportunities to improve these ICT skills. Fakhra & Mahar diagnosed descriptively the impact of training on teachers competencies on three categories of competencies: pedagogical, assessment & management and research competencies. Trained teachers showed a significant difference in pedagogical competencies, management and assessment competencies and research competencies. It depicts that in all the categories trained teachers were more competent than teachers having no training. These previous studies focused generally on the competencies of teachers and lecturers in the basic education level. The competencies required for teaching in the K to 12 program might be at a varying degree when compared to those faculty teaching in the graduate school programs. 6 CC The Journal Vol. 13 Oct. 2017 Faculty Development Faculty development is a process of enhancing and promoting any form of academic scholarship in individual faculty members. It refers to programs and strategies that aim both to maintain and to improve the professional competence of faculty members in fulfilling their tasks in the higher education institutes. It includes programs or activities that lead to expand the interests, improve the competence, and facilitate the professional and personal growth of faculty members in order to improve the quality of faculty instruction, research and student advisement. There exist several definitions for the faculty development and its dimensions. Besides the similarities between faculty development definitions, there is an overlap among its defined dimensions. According to Scott (1990), in 1979 the American Association for Higher Education proposed a definition for faculty development, which went beyond the then dominant emphasis on teaching. Based on this definition, faculty development is the theory and practice of facilitating improved faculty performance in a variety of domains, including the intellectual, the institutional, the personal, the social, and the pedagogical. Faculty development can also be defined as any planned activity designed to improve an individual's knowledge and skills in areas considered essential to the performance of a faculty member. The aim is to improve faculty members’ competence as teachers and scholars. Hence, colleges and universities try to renew and maintain vitality of their staff. Prachyapruit (2001) defined faculty development programs as activities that are designed to help faculty members improve their competence as teachers and scholars. In general, faculty development is addressed to faculty in all disciplines and to administrators who wish to help shaping an environment in which student learning can flourish. According to Daigle and Jarmon (1997) faculty development is an important component of building and maintaining human capital, which in turn is part of the total capital assets of the university. Much like the supporting physical and technology infrastructures, intellectual capital should be planned and managed around broad institutional goals for the future. Hitchcock and Stritter (1992), suggest that the concept of faculty development is evolving and expanding. Faculty development, originally defined as the improvement of teaching skills, has expanded to include all areas of a faculty member’s responsibility. Higher education cannot simply rely on current methods of faculty preparation because these methods may leave instructors unprepared for the 7 CC The Journal Vol. 13 Oct. 2017 challenges of the twenty-first century (Miller, 1997). Cohen, Manion and Morrison, (1996), believe that even being able to update with the developments due to exponential increase in knowledge and information and use of new technologies, has become a major challenge for faculties. It is unavoidable that the extended use of information technology will bring a revolution in teaching and learning, just as it has brought a revolution in knowledge and its acquisition. Part of becoming a scholar is to live with the fact that complete mastery of a particular subject is not possible. Also, the rate at which technology is developing compounds the lack-of-mastery feeling of professors. In some instances, technology is growing at a rate that exceeds professors’ ability to assimilate and use new information before the knowledge is already obsolete. Faculty development represents an investment in human capital. Educational institutions receive a return on this investment in the form of an improved institution over time. Disciplines also receive a return through improved research and better training or the next generation of the profession provided by the graduates of faculty development programs. The return to individual faculty members comes in the form of improved vitality and growth that can help sustain them in their academic careers. Faculty development has high payoff potential; thus it is important to design and implement effective programs (Hitchcock & Stritter, 1992). Faculty development can play a significant role in fostering an environment conducive to valuing a broad definition of scholarship, especially with respect to what constitutes the scholarship of teaching (Watson, Grossman, 1994). It is required in higher education institutes since it develops and reinforces the abilities of faculty members. It leads faculty members to operate with increasing autonomy while having an extensive view of new educational reforms. They are prepared to work more effectively as individuals and also as members of a society through faculty development programs. They should understand themselves and their functions very well in order to improve their teaching as a part of developing the education system. Steinert (2000) highlighted that academic vitality is dependent upon faculty members’ interest and expertise. In addition, faculty development has a critical role to play in promoting academic excellence and innovation. Faculty members, by better understanding of themselves and their social environment, can promote such developments. In general, faculty development programs, whatever their nature, are essential if universities are to respond to changes in (a) expectations about the quality of undergraduate education, (b) views regarding the nature and value of assessment, (c) societal needs, (d) technology 8 CC The Journal Vol. 13 Oct. 2017 and its impact on education, (e) the diverse composition of student populations, and (f) paradigms in teaching and learning (Millis, 1994). A good faculty development program is a process designed to create a climate where recognition, institutional support and professional development are addressed (Pendleton, 2002). In summary, the purposes for faculty development programs are: improving teaching, improving faculty scholarship, personal development, curriculum development, and institutional development. While the purpose remains constant, the emphasis given to any of these components varies in different institutions. Thus, professional development should be designed around researchdocumented practices that enable educators to develop the skills necessary to implement what they are learning. Marzano, Pickering, and Pollock (2001) have identified nine research- documented practices that improve student performance. Those practices should also be applied to the improvement of teacher effectiveness via professional development ((Harwell, 2003). STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM This study for graduate faculty professional development (PD) program was designed to answer the following specific questions. 1. What are the training needs of graduate faculty members based from the expected performance standards? 2. What graduate faculty professional development (PD) program can be proposed? METHODOLOGY Research Design The descriptive-cross-sectional design of research was used in the study to obtain information concerning the analysis of the training needs of the graduate faculty members. Participants The respondents of the study were the faculty members of the graduate school with at least three teaching loads during the thIrd trimester. There were 16 faculty member subjected to the trimestral evaluation conducted by the Office of the Graduate School. All of them finished doctorate degrees in various specializations such as educational administration, business 9 CC The Journal Vol. 13 Oct. 2017 management, and public administration. Majority of them have been in the graduate school teaching for more than 10 years now. Instrument An instrument on the performance standards was patterned and tailored from the survey-questionnaire of the Philippine Association of Colleges and Universities-Commission on Accreditation (PACUCOA) used during the preliminary visit to the various graduate programs of the College. The specific requirements on professional performance, instructional procedures and techniques, and evaluation and grading were used as the criteria. The same instrument was used for the purposes of determining the training needs of the faculty. To assess the performance standards for graduate faculty, there are 10 items under professional performance (endeavors to achieve the objectives of the graduate school and of the program); 10 items related to instructional procedures and techniques (provides a functional and well-planned syllabus which specifies the target competencies, research and class activities required for course); and seven items for evaluation and grading (uses valid techniques to evaluate student performance). The instrument used the 5 point Likert scale with the corresponding descriptive ratings and analysis for the possible areas for CPD: (1) Descriptive Rating (DR). (5) 5.00-4.20= Outstanding Competence (OC); (4) 4.19-3.40= Very Satisfactory Competence (VSC); (3) 3.39-2.60= Satisfactory Competence (SC); (2) 2.591.80= Fair Competence (FC); (1) 1.79-1.00= No Competence (NC); (2) Analysis: (5) 5.00-4.20= Not Needed (NN); (4) 4.19-3.40= Sometimes Needed (SN); (3) 3.392.60= Needed (N); (2) 2.59-1.80= Much Needed (MN); (1) 1.79-1.00= Very Much Needed (VMN). These criteria were subjected to face and construct validity by the previous administrators of the graduate school after taking into consideration the expected performance standards for graduate faculty by an external accrediting agency. Procedure Data were gathered towards the end of the third trimester for the Academic Year 2015-2016 among the graduate faculty. The Dean conducted face-to-face and personal assessment using the instrument. Each faculty was formally introduced to the purposes of the study and assured of the strict confidentiality of the data gathered. 10 CC The Journal Vol. 13 Oct. 2017 The level of competence of the faculty relative to the specific indicators of the performance standards could be the basis for the analysis towards professional development activities. Thus, it determines the gap between what is expected as to the level of competence and the trainings needed to improve such professional performance. RESULTS 1. Competencies and Analysis for Professional Development Program in Relation to Professional Performance Table 1 depicts the competencies of faculty members in relation to professional performance. The following specific indicators such as “endeavors to achieve the objectives of the graduate school and of the program, prepares well for his/her class, shows mastery of subject matter, relates current issues and community needs with the subject matter, and participates in the activities of professional organizations” are rated as “Outstanding Competence”. One indicator which is “manifests awareness of modern educational trends” is rated as “Very Satisfactory Competence”. Table 1 Performance and Analysis for Professional Development Program in Relation to Professional Performance Performance Standards (PS) and Indicators PS 1: Professional Performance 1) endeavors to achieve the objectives of the graduate school and of the program. 2) manifests awareness of modern educational trends. 3) prepares well for his/her class. 4) shows mastery of subject matter. 5) demonstrates mastery of research skills as evidenced by his/her own research output. 6) relates current issues and community needs with the subject matter. 7) assists graduate students in developing research competencies. 8) shows professional growth through further studies, research activities and publications. 9) participates in the activities of professional organizations. 10) shares their knowledge or expertise with other institutions, agencies and the community. M DR Analysis 4.79 4.19 4.28 OC VSC OC Not Needed Sometimes Needed Not Needed 4.56 OC Not Needed 3.17 SC Needed 4.58 OC Not Needed 3.16 SC Needed 3.10 SC Needed 4.53 OC Not Needed 3.21 SC Needed Note. DR= Descriptive Rating 11 CC The Journal Vol. 13 Oct. 2017 The rests of the indicators to include “demonstrates mastery of research skills as evidenced by his/her own research output, assists graduate students in developing research competencies, shows professional growth through further studies, research activities and publications, and shares their knowledge or expertise with other institutions, agencies and the community” are rated “Satisfactory Competence”. Thus, based on the analysis, the specific indicators of professional standards such as “demonstrates mastery of research skills as evidenced by his/her own research output, assists graduate students in developing research competencies, shows professional growth through further studies, research activities and publications, and shares their knowledge or expertise with other institutions, agencies and the community” are the identified areas for professional development program among graduate school faculty. 2. Performance and Analysis for Professional Development Program in Relation to Instructional Procedures and Techniques Table 2 reveals the competencies of faculty members in relation to instructional procedures and techniques. Table 2 Performance and Analysis for Professional Development Program in Relation to Instructional Procedures and Techniques Performance Standards(PS) and Indicators PS 2: Instructional Procedures and Techniques 1) provides a functional and well-planned syllabus which specifies the target competencies, research and class activities required for course. 2) provides opportunities for independent study. 3) includes research requirement for each subject. 4) utilizes instructional materials with depth and breadth expected for the graduate level. 5) requires students to make extensive use of print and nonprint reference materials. 6) demonstrates research techniques aimed at fulfilling the requirements of the course/s. 7) uses varied methods and innovative approaches (seminars, fora, field observations, problem-based discussion). 8) uses instructional procedures and techniques to encourage active students’ interaction. 9) uses interdisciplinary and/or multidisciplinary approaches whenever possible. 10) enforces definite rules and policies for effective classroom management. M DR Analysis 4.19 Sometimes Needed 4.63 3.22 VS C OC SC 4.61 OC Not Needed 4.52 OC Not Needed 3.17 SC Needed 4.12 Sometimes Needed 4.25 VS C OC 4.63 OC Not Needed 4.32 OC Not Needed Not Needed Needed Not Needed 12 CC The Journal Vol. 13 Oct. 2017 As revealed, the faculty members showed “Outstanding Competence” relative to the following indicators: “provides opportunities for independent study, utilizes instructional materials with depth and breadth expected for the graduate level, requires students to make extensive use of print and non-print reference materials, uses instructional procedures and techniques to encourage active students’ interaction, uses interdisciplinary and/or multidisciplinary approaches whenever possible, and enforces definite rules and policies for effective classroom management. They are rated “Very Satisfactory Competence” on the indicators such as “provides a functional and wellplanned syllabus which specifies the target competencies, research and class activities required for course”, and “uses varied methods and innovative approaches (seminars, fora, field observations, problem-based discussion”. Moreover, they are rated “Very Satisfactory Competence” on the indicators such as “provides a functional and well-planned syllabus which specifies the target competencies, research and class activities required for course”, and “uses varied methods and innovative approaches (seminars, fora, field observations, problem-based discussion”. However, they showed “Satisfactory Competence” on the areas such as “includes research requirement for each subject, and demonstrates research techniques aimed at fulfilling the requirements of the course/s.” Thus, based on analysis, continuous professional development for upgrading of skills and knowledge on the preparation of well-planned syllabus which specifies the target competencies, research and class activities required for course”, and use of varied methods and innovative approaches such as seminars, fora, field observations, problem-based discussion must be explored and implemented. 3. Performance and Analysis for Professional Development Program in Relation to Evaluation and Grading Table 3 shows the level of competencies of the faculty members in terms of evaluation and grading of students’ outcomes. As revealed, the faculty members are “Outstanding” in the explaining the grading policy to students, using researches, term papers, projects and other requirements as indicators of the scholarly level of student achievement in every course, and in giving final examination to measure the breadth and depth of student’s competencies; ability to apply current findings and principles on one’s field of specialization; command of written communication; and the ability to analyze and synthesize ideas. 13 CC The Journal Vol. 13 Oct. 2017 Table 3 Performance and Analysis for Professional Development Program in Relation to Evaluation and Grading Performance Standards (PS) and Indicators PS 3: Evaluation and Grading 1) uses valid techniques to evaluate student performance. 2) explains the grading policy to students. 3) uses researches, term papers, projects and other requirements as indicators of the scholarly level of student achievement in every course. 4) gives final examination to measure: 4.1 the breadth and depth of student’s competencies; M DR Analysis 4.19 4.21 VSC OC Sometimes Needed Not Needed 4.57 OC Not Needed 4.46 OC Not Needed 4.2 ability to apply current findings and principles on one’s field of specialization; 4.32 OC Not Needed 4.3 command of written communication; 4.54 OC Not Needed 4.5 the ability to analyze and synthesize ideas. 4.33 OC Not Needed However, they are “Very Satisfactory” on the use of valid techniques to evaluate student performance. Thus, the only indicator relative to evaluation and grading of students’ outcomes for possible faculty development activity is on the use of valid techniques to evaluate student performance. DISCUSSION Relative to professional performance standards, the findings show that the graduate faculty members were outstanding in achieving the objectives of the graduate school and of the program, preparing for his/her class, shows mastery of subject matter, relating current issues and community needs with the subject matter; and in participating to the activities of professional organizations. However, they were just satisfactory in demonstrating mastery of research skills as evidenced by their own research output, assisting graduate students in developing research competencies, showing professional growth through further studies, research activities and publications, and sharing their knowledge or expertise with other institutions, agencies and the community. In terms of instructional procedures and techniques as standards, the faculty members were outstanding in providing opportunities for independent study, utilizing instructional materials with depth and breadth expected for the graduate level, requiring students to make extensive use of print and non-print reference materials, using instructional procedures and techniques to encourage active students’ interaction; using interdisciplinary and/or multidisciplinary 14 CC The Journal Vol. 13 Oct. 2017 approaches whenever possible; and enforcing definite rules and policies for effective classroom management. However, they were very satisfactory in providing a functional and wellplanned syllabus which specifies the target competencies, research and class activities required for course, and in using varied methods and innovative approaches (seminars, fora, field observations, problem-based discussion. They only showed satisfactory in research requirement for each subject, and demonstrate research techniques aimed at fulfilling the requirements of the course/s. As to evaluation and grading as performance indicator, the faculty were outstanding in the explaining the grading policy to students, using researches, term papers, projects and other requirements as indicators of the scholarly level of student achievement in every course, and in giving final examination to measure the breadth and depth of student’s competencies, ability to apply current findings and principles on one’s field of specialization, command of written communication, and the ability to analyze and synthesize ideas, and they were very satisfactory on the use of valid techniques to evaluate student performance. The findings imply that the training needs of graduate faculty members are relative to the development research skills so that they could produce research output of their own. These skills in doing research are much needed to assist students in the conceptualization and implementation of their own research. Professional growth and development through further studies, research activities and publications, and sharing of knowledge or expertise with other institutions, agencies and the community can be initiated among faculty members. Attendance to in-service training programs relative trends and issues in education can also be implemented for the faculty to manifest awareness of modern educational trends. Changes to the role of the faculty member in higher education require alteration in faculty preparation. There has been a decrease in higher education budgets, which have often led to cuts in faculty development funding, decreased support for students, and increased pressure to acquire outside funding (Mitchell & Leachman, 2015). Despite these cuts to faculty development, faculty accountability for student learning has increased. The multiple roles faculty play requires skills in research, teaching, and service. This requires faculty members to: understand students, learn new technologies, deal with societal demands for accountability, balance the tripartite workload of faculty, and understand the changing job market. Ortlieb, Biddix, and Doepker (2010) have argued that support for faculty should include developing faculty 15 CC The Journal Vol. 13 Oct. 2017 communities that (1) foster positive relationships with other faculty members, (2) encourage partnerships for research, (3) provide a network of support, (4) encourage critical reflection, and (5) offer monthly support groups to help faculty members develop into their roles. The graduate faculty research efficacy needs to be developed for them to engage in research productivity. In order for them to develop research selfefficacy, the faculty needs to (1) conduct research related to productivity among students (Kahn, 2001), (2) attend research training and willing to conduct research (Love et al. 2007), (3) develop information seeking skills and research methodology skills (Meehra et al. (2011), (4) pursue research beyond graduate study (Forester et al. 2004), (5) involve in the design of action research-enriched teacher education program (Mahlos & Whitfield, 2009) and assertion of research skills development in pre-service teacher education (Tamir, 2012), (6) develop professional curiosity and insight (Rudduck, 2015), (7) attend self-support evening programs (Butt & Shams, 2013), (8) involve in research during pre-service training (Siemens, Punnen, Wong & Kanji, 2010), (9) perform research related tasks and activities (Mullikin et al., 2007), (10) write research articles for publication (Forester et al. 2004), (11) connected to both future research involvement and higher research productivity (Lei, 2008; Bieschke, 2006; Hollingsworth and Fassinger, 2002; Khan, 2001; Bard et al. 2000; Bieschke et al. 1996), (12) develop advisee–adviser relationships (Schlosser and Gelso (2001), (13) active participation in a course of a semester (Unrau & Beck (2005), (14) gain enough amount of research experience (Bieschke et al. 1996), and (15) maintain a contusive academic research training environment (Hollingsworth & Fassinger, 2002; Kahn, 2001). The findings revealed that research capability building programs and activities among graduate faculty members is the first priority in the faculty development program. This activities will surely hone their competencies and efficacies in research skills as evidenced by his/her own research output; assisting their students in developing research competencies; and eventually showing professional growth through further studies, research activities and publications; and sharing their knowledge or expertise with other institutions, agencies and the community. Regular attendance to in-service training programs relative trends and issues in education can also be implemented for the faculty to manifest awareness of modern educational trends. It is undeniably essential to consider administrative support and include in the Professional Development (PD) the need to continually upgrade the graduate school faculty research preparation, publication, dissemination and utilization. 16 CC The Journal Vol. 13 Oct. 2017 REFERENCES Alalfy, H. R. (2015). Some modern trends in educational leadership and its role in developing the performance of the Egyptian secondary school managers. American Journal of Educational Research, 3(6), 689-696 Al-Sakarneh, B. (2011). New trends in training. Amman: Nigeria: Dar Al-Maseerah. Akinnagbe O. M. (2011). Training needs analysis of lecturers for information and communication technology (ICT) skills enhancement in Faculty of Agriculture, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. African Journal of Agricultural Reseearch, 6(32), 6635– 6646. Bard, C. C., Bieschke, K. J., Herbert, J. T., & Eberz, A. B. (2000). Predicting research interest among rehabilitation counseling students and faculty. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 44(1), 48-55. Bieschke, K. J. (2006). Research self-efficacy beliefs and research outcome expectations: implications for developing scientifically minded psychologists. Journal of Career Assessment, 14(1), 77-91. Bieschke, K. J., Bishop, R. M., & Garcia, V. L. (1996). The utility of the research selfefficacy scale. Journal of Career Assessment, 4(1), 59-75. Bowen, H. R., & Schuster, J.H. (1986). American Professors: A National Resource Imperiled. N Y: Oxford University Press. Brooks, C. F. (2010). Toward ‘hybridised’ faculty development for the twenty-first century: Blending online communities of practice and face-to-face meetings in instructional and professional support programmes. Innovation in Education and Teaching International, 47(3), 261-270. Butt, I. H., & Shams, J. A. (2013). Student Attitudes towards Research: A comparison between two public sector universities in Punjab, South Asian Studies. American Journal of Educational Research, 4(6), 484-487. Chism, N. V. N., Lees, Douglas, N., & Evenbeck, S. (2002). Faculty development for teaching. Liberal Education, 88(3), 34-41. Chun, J. (1999). A National Study of Faculty Development Need in Korean Junior Colleges. Retrieved from http://www.learntechlib.org/noaccess/21528 Clemeña, R. M., & Acosta, S. A. (2006). Developing research culture in Philippine Higher Education Institutions: Perspectives of University Faculty. Retrieved from http://portal.unesco.org/education/en/files/54062/11870006385Rose_Marie_Cl emena.pdf/Rose_Marie_Clemena.pdf Daigle, S. L., & Jarmon, C. G. (1997). Building the campus infrastructure that really counts. Educom Review, 97(32), 35. Fakhra, A., & Mahar, M. S. (2014). Impact of Training on Teachers Competencies. Journal of Arts, Science & Commerce, 5(1), 121–128. 17 CC The Journal Vol. 13 Oct. 2017 Fakhra, A. (2012). Impact of faculty professional development program of HEC on teachers competencies and motivation at higher education level in Pakistan. International Refereed Research Journal, 5(1), 121-128. Forester, M (2004). Factor structures of three measures of research self-efficacy. Journal of Management, 34(3), 47 Gelso, C. J., & Lent, R. W. (2000). Scientific training and scholarly productivity: The person, the training environment, and their interaction. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Handbook of Counseling Psychology (pp 109-139). NY: John Wiley. Green, K. E., & Kvidahl, R. P. (1989). Teachers as researchers: Training, attitudes and performance. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED307248.pdf Griffin, B. W. (n.d.). Graduate student self-efficacy and anxiety toward the dissertation process. Retrieved from http://coe.georgiasouthern.edu/foundations/bwgriffin/edur9131/EDUR_9131_ sample_research_study__disser tation_process.pdf Harris, B. (1980). Improving staff performance through in-service education. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, Inc. Harwell, S. (2003). Teacher professional development: It’s not an event, it’sa process. Waco, TX: CORD. Heppner, P., Paul, [initial], & Johnson, J. A. (1994). New horizons in counseling: Faculty development. Journal of Counseling & Development, 72(5), 1-160. Hitchcock, M. A. & Stritter, F. T. (1992). Faculty development in the health profession: Conclusions and recommendations. Medical Teacher, 14(4), 295-309. Hollingsworth, M. A., & Fassinger, R. E. (2002). The role of faculty mentors in the research training of counseling psychology doctoral students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 49(3), 324-330 Hussain, S., Sarwar, M., Khan, N., .& Khan, I. (2010). Faculty development program for university teachers: Trainee’s perception of success. European Journal of Scientific Research, 44(2), 253-257. International Management in Higher Education (IMHE) (2015). Learning our lesson: Review of quality teaching in higher education. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/edu/imhe/44058352.pdf Kahn, J. H. (2001). Measuring global perceptions of the research training environment using a short form of the RTES-R. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 33(2), 103-119. Khan, M. N., & Sarwar, M. (2011). Needs assessment of university teachers for professional enhancement. International Journal of Business and Management, 6(2), 208– 212. Kahn, J. H., & Scott, N. A. (2001). Predictors of research productivity and science related career goals among counseling psychology graduate students. The Counseling Psychologist, 1(3), 193-203 Kala, D., & Chaubey, D. S. (2015). Attitude of Faculty Members towards Faculty Development Programs and their Perceived Outcomes. Retrieved form http://pbr.co.in/August2015/2.pdf 18 CC The Journal Vol. 13 Oct. 2017 Lei, S. A. (2008). Factors changing attitudes of graduate school students toward an introductory research methodology course. Education, 128(4), 667-685 Love, K. M., Bahner, A. D., Jones, L. N., & Nilson, J. E. (2007). An investigation of early research experience and research self-efficacy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 38(3), 314-320 Meerah, T., (2011). Action research: Teachers as researchers in the classroom. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Miller, A. A. (1997). ERIC review—back to the future: Preparing community college faculty for the millennium. Community College Review, 25(1), 83. Millis, B. (1994). Faculty development in the 1990s: What it is and why we can't wait. Journal of Counseling & Development, 72(5), 454. Mitchell, M., & Leachman, M. (2015). Years of cuts threaten to put college out of reach for more students. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Retrieved from http://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/5- 13-sfp.pdf Mullikin, E. A., Bakken, L. L., & Betz, N. E. (2007). Assessing research self-efficacy in Physician-Scientists: The clinical research appraisal inventory. Journal of Career Assessment, 15(3), 367-387. Nathan, Peter E. (1994). Who should do faculty development and what should it be? Journal of Counseling & Development, 72(5), 508–509. Ortlieb, E. T., Biddix, J. P., & Doepker, G. M. (2010). A collaborative approach to higher education induction. Active Learning in Higher Education, 11(2), 109-118. Pendleton, E. P. (2002). Re-Assessing Faculty Development. Retrieved from https://www.questia.com/magazine/1P3-242021631/re-assessing-facultydevelopment POD (Professional and Organizational Development Network in Higher Education). (2003). Retrieved June 27, 2003 from http://www.podnetwork.org/ developments/ definitions.htm Prachyapruit, Apipa (2001). Socialization of New Faculty at a Public University in Thailand. Michigan State University, Department of Educational Administration. Retrieved from http://library1.nida.ac.th/ejourndf/tjpa/tjpa-v03n03/tjpav03n03_c04.pdf Rowbotham, M. A. (2015). The impact of faculty development on teacher, International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship , 7(1), 1-28. Rudduck, J. (2015). Teacher research and research-based teacher education. Retrieved from https://www.sensepublishers.com/media/2524-transformative-teacherresearch.pdf Schlosser, L. Z., & Gelso, C. J. (2001). Measuring the working alliance in advisor advisee relationships in graduate school. Retrieved from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1069072714523086 Schuster, J. H., Wheeler, D. W., & Associates. (1990). Enhancing faculty careers: Strategies for development and renewal. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. 19 CC The Journal Vol. 13 Oct. 2017 Scott, J. H. (1990). Role of community college department chairs in faculty development. Retrieved from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/009155219001800304 Selvi, K. (2010) Teachers’ Competencies Culturas. Retrieved from http://www.academia.edu/2648770/Teachers_Competencies Shaikh, F. M., Goopang, N. A., & Junejo M.A. (2008). Impact of training and development on the performance of university teachers, a case study in Pakistan. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/education_culture/repository/education/policy/strategi c-framework/doc/teacher-development_en.pdf Shkedi, A. (1998). Teachers' attitudes towards research: A challenge for qualitative researchers, International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 11(4), 559-577 Siddiqui,A. Aslam,H. Farhan,H. Luqman, A., & Lodhi, M. (2011). Minimizing potential issues in higher education by professionally developing university teachers. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260791102_Minimizing_Potential_Iss ues_in_Higher_Education_by_Professionally_Developing_University_Teachers Siemens, D. R., Punnen, S., Wong, J., & Kanji, N. (2010). A survey on the attitudes towards research in medical school. Retrieved from http://bmcmededuc.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1472-6920-10-4 Simpson, E. L. (1990). Faculty renewal in higher education. Retrieved from http://isbn-title.ru/Faculty-renewal-in-higher-education--or--cby-Edwin-LSimpson/5/chaahd Stanford University (2015). On the Future of Engagement: Tomorrow's Academy. Retrieved from https://tomprof.stanford.edu/posting/931 Steinert, Y. (2000). Faculty development in the new millenium: Key challenges and future directions. Retrieved from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01421590078814 Stokking, K., van der Schaaf, M., Jaspers, J., & Erkens, G. (2004). Teachers’ assessment of students’ research skills. British Educational Research Journal, 30(1), 93–116. Tamir, P. (2012). Incorporating research into preservice teacher education. South pacific journal of teacher education, 3(4), 287-298. Trower, C. A., & Gallagher, A. (2010). Trekking toward tenure: What pre-tenure faculty want on the journey. Metropolitan Universities, 21(2), 16-33. Unrau, Y. A., & Grinnell Jr, R. M. (2005). The impact of social work research courses on research self-efficacy for social work students. Social Work Education, 3(1), 4. Unrau, Y. A., & Beck, A. R. (2005). Increasing research self-efficacy among students in professional academic programs. Innovative Higher Education, 10(2), 42–56. Retrieved from http://eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk/13414/2/Quinney_and_Parker_6.7.09edited.p df 20 CC The Journal Vol. 13 Oct. 2017 Watson, G.. & Grossman, L. H. (1994). Pursuing a comprehensive faculty development program: Making fragmentation work. Journal of Counseling & Development, 72(5), 465-473 Wedman, J. M., Mahlos, M. C., & Whitfield, J. (1989). Perceptual differences regarding the implementation of an inquiry-oriented student teaching curriculum. Journal of Research and Development in Education, 22(4), 29-35. Wilkerson L., & Irby DM. (1998). Strategies for improving teaching practices: A comprehensive approach to faculty development. Academic Medicine, 73(4), 387396. Williams, E. G. (2004). Academic, Research, and Social Self-Efficacy among African American Pre-McNair Scholar Participants and African American Post-McNair Scholar Participants. Retrieved from goo.gl/wrsxwc 21