9biograficrossegore

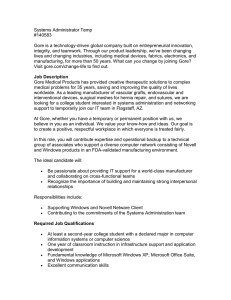

advertisement