ReGenerating Community

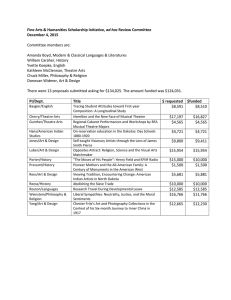

advertisement