4) Guidelines – Indolent NHL(2005)

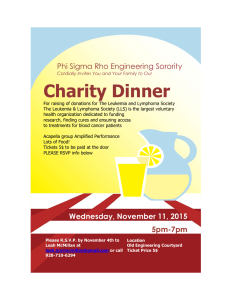

advertisement