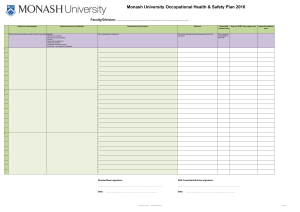

Regulatory Impact Statement for proposed Occupational Health and

advertisement