Designing a Syllabus for ESP Learners: The Case of 2 Year

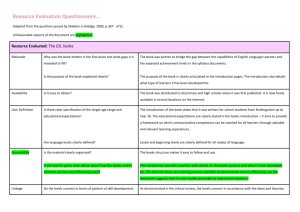

advertisement