Source Identification of Atlanta Aerosol by Positive Matrix Factorization

advertisement

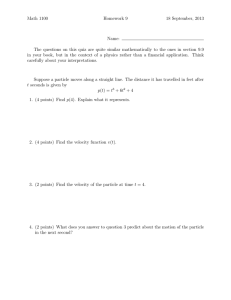

TECHNICAL PAPER ISSN 1047-3289 J. Air & Waste Manage. Assoc. 53:731–739 Copyright 2003 Air & Waste Management Association Source Identification of Atlanta Aerosol by Positive Matrix Factorization Eugene Kim and Philip K. Hopke Department of Chemical Engineering, Clarkson University, Potsdam, New York Eric S. Edgerton Atmospheric Research and Analysis, Inc., Durham, North Carolina ABSTRACT Data characterizing daily integrated particulate matter (PM) samples collected at the Jefferson Street monitoring site in Atlanta, GA, were analyzed through the application of a bilinear positive matrix factorization (PMF) model. A total of 662 samples and 26 variables were used for fine particle (particles ⱕ2.5 m in aerodynamic diameter) samples (PM2.5), and 685 samples and 15 variables were used for coarse particle (particles between 2.5 and 10 m in aerodynamic diameter) samples (PM10 –2.5). Measured PM mass concentrations and compositional data were used as independent variables. To obtain the quantitative contributions for each source, the factors were normalized using PMF-apportioned mass concentrations. For fine particle data, eight sources were identified: SO42⫺-rich secondary aerosol (56%), motor vehicle (22%), wood smoke (11%), NO3⫺-rich secondary aerosol (7%), mixed source of cement kiln and organic carbon (OC) (2%), airborne soil (1%), metal recycling facility (0.5%), and mixed source of bus station and metal processing (0.3%). The SO42⫺-rich and NO3⫺-rich secondary aerosols were associated with NH4⫹. The SO42⫺-rich secondary aerosols also included OC. For the coarse particle data, five sources contributed to the observed mass: airborne soil (60%), NO3⫺-rich secondary aerosol (16%), SO42⫺-rich secondary aerosol (12%), cement kiln (11%), and metal recycling facility (1%). Conditional probability functions were computed using surface wind data and identified mass contributions IMPLICATIONS PMF has been applied to PM2.5 and PM10 –2.5 composition data derived from samples collected in Atlanta. The results for the two sets of samples illustrate the use of PMF as a data analysis tool for identifying and apportioning PM sources in these size ranges. With the likelihood of a PM10 –2.5 standard being promulgated along with the PM2.5 standard after the current round of National Ambient Air Quality Standards review, such methods will be needed as part of the planning process for implementing the air quality standards for PM. Volume 53 June 2003 from each source. The results of this analysis agreed well with the locations of known local point sources. INTRODUCTION An association between particulate matter (PM) concentrations and adverse health effects has been found in many studies.1–3 Since the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency promulgated new National Ambient Air Quality Standards for airborne PM, a number of additional air quality and epidemiology studies have been undertaken.4 – 6 The Southeastern Aerosol Research and Characterization (SEARCH) study was begun in early 1998. In this study, instrumentation for daily sampling and continuous PM mass and composition, gases, and meteorology measurements were deployed at eight monitoring stations over a broad geographical region in the southeastern United States. The objectives of the SEARCH study are to obtain an understanding of PM composition and its seasonal and regional variability in southeastern U.S. states, develop PM climatology, and estimate source contributions. As a part of the SEARCH study, advanced source apportionment methods for airborne PM, such as positive matrix factorization (PMF), are being applied to the data. PMF7 has been shown to be a powerful alternative to traditional receptor modeling of airborne PM.8 –10 PMF has been successfully used to assess particle source contributions in the Arctic,11 Hong Kong,12 Phoenix, AZ,13 Thailand,14 Vermont,15 and three northeastern U.S. cities.16 The objectives of this study are to identify PM sources and estimate their contributions to the particle mass concentrations. In the present paper, PMF was applied to a particle compositional data set of daily samples collected during a two-year period at a single monitoring site in Atlanta, GA. The resolved particle sources of ambient fine (particles ⱕ2.5 m in aerodynamic diameter) particles (PM2.5) and coarse (particles between 2.5 m and 10 m in aerodynamic diameter) particles (PM10 –2.5) and their seasonal trends are discussed. To help identify the likely locations of the PMF-identified sources, a conditional Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 731 Kim, Hopke, and Edgerton probability function (CPF) was calculated. The results of this study could be useful in the understanding of local particle sources and could assist in air quality management. SAMPLE COLLECTION AND CHEMICAL ANALYSIS The particle compositional data utilized in this study consisted of measurements taken between August 1998 and August 2000 at a monitoring site (Jefferson Street) located 4 km northwest of downtown Atlanta. The Jefferson Street site is located in an industrial and commercial area, shown in Figure 1. Coarse particle samples were collected using a conventional dichotomous sampler (Andersen Instruments, Inc.). Daily integrated fine particle samples were collected using the particulate composition monitor (PCM) (Atmospheric Research and Analysis, Inc.), which has three independent sampling lines, shown in Figure 2. Each sampling line has a 10-m cyclone followed by a Well Impactor Ninety-Six, which has a 2.5-m cutoff size in particle aerodynamic diameter.17,18 The PCM permits simultaneous sampling on a three-stage filter pack (Teflon, nylon, and cellulose filter), nylon filter, and quartz filter. The PCM includes carbonate denuders and citric acid denuders upstream of both the three-stage filter and the nylon filter. The quartz filter includes an upstream carbon denuder to remove gaseous organic materials. Chemical analysis was performed on the Teflon filters of the three-stage filter pack samples via energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence (XRF)19 by Chester LabNet, Inc. Nylon and cellulose filters of the three-stage filter pack samples were analyzed via ion chromatography (IC) for NO3⫺ and NH4⫹. The nylon filters of the independent sampling line were analyzed via IC for SO42⫺, NO3⫺, and NH4⫹. The quartz filter was cut in half and analyzed via thermal optical reflectance/Interagency Monitoring of Protected Visual Environments protocol for organic carbon (OC) and elemental carbon (EC) by Desert Research Insti- Figure 1. Location of the Jefferson Street monitoring site in Atlanta, GA. 732 Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association Figure 2. Schematic of the PCM. tute. For the fine particle data, 662 daily samples collected between August 1998 and August 2000 and 26 species were used. XRF S and SO42⫺ showed excellent correlations (slope ⫽ 3.1, r2 ⫽ 0.99), so it is reasonable to exclude XRF S from the analysis. Analysis of the compositional data revealed a mass closure problem for the fine particle samples. In Figure 3, the fine mass concentrations measured using the three-stage filter are compared with the summations of fine particle species excluding crustal elements (Al, Si, K, Ca, Fe) that would normally be associated with O2. Approximately 27% of the measured mass concentrations were smaller than the summations of species concentrations. This mass closure problem is thought to be caused by the loss of semivolatile OC.20,21 The loss of NO3⫺ mass on the Teflon filter was accounted for by the subsequent nylon filter in the Figure 3. Time-series plot of measured mass concentration minus summation of measured species for fine particles. Volume 53 June 2003 Kim, Hopke, and Edgerton three-stage filter pack. This additional mass of NO3⫺ was added to the measured particle mass from the Teflon filter. This mass closure issue (sum of species ⬎ particle mass) presents a problem for the multilinear regression analysis that has generally been used in PMF analysis. Therefore, the alternative approach described in the next section was employed. For the coarse particle data, 685 samples collected between July 1998 and December 2000 and 15 species were available. OC and EC were not measured. In coarse particle data, approximately 53% of the XRF S values were smaller than SO42⫺/3. This result suggests that XRF S concentrations were underestimated where it is surmised that the problem is X-ray penetration losses. For this reason, the XRF S was excluded from the analysis of coarse particle data. Summaries of the fine and coarse PM species used in this study are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. 冘 p x ij ⫽ gikfkj ⫹ eij (1) k⫽1 where xij is the jth species concentration measured in the ith sample, gik is the particulate mass concentration from the kth source contributing to the ith sample, fkj is the jth species mass fraction from the kth source, eij is residual associated with the jth species concentration measured in the ith sample, and p is the total number of independent sources. The corresponding matrix equation is X ⫽ GF ⫹ E (2) where X is an n ⫻ m data matrix with n measurements and m number of elements; E is an n ⫻ m matrix of residuals; G is an n ⫻ p source contribution matrix with p sources; and F is a p ⫻ m source profile matrix. As pointed out by Henry,25 there are an infinite number of possible solutions to the factor analysis problem (rotations of G matrix DATA ANALYSIS The general receptor modeling problem can be stated in terms of the contribution from p independent sources to all chemical species in a given sample as follows:22–24 Table 1. Summary of fine particle mass and 25 species concentrations used for PMF modeling. Concentration (ng/m3) Species Geometric Mean Arithmetic Mean 15871 4488 2485 877 82 1643 4024 1.0 17 2.9 2.0 1.4 3.7 2.0 0.93 3.9 3.6 12 0.54 0.51 0.62 11 191 65 61 102 18029 5579 2920 1124 108 1982 4495 1.5 19 4.2 3.8 2.0 6.6 3.5 1.4 4.4 5.0 17 0.61 0.57 0.46 29 253 81 78 132 PM2.5 SO42⫺ NH4⫹ NO3⫺ Cl EC OC As Ba Br Cu Mn Pb Sb Se Sn Ti Zn Cr Ni V Al Si K Ca Fe a a Number of BDLb Min 1930 526 298 127 21 227 878 0.47 13 0.26 0.59 0.37 1.1 1.9 0.32 3.2 2.0 0.42 0.47 0.47 0.27 5.7 23 7.7 4.6 13 Max Values (%) Number of Missing Values (%) 49264 20851 10314 6014 613 10234 22089 11 57 204 42 13 78 105 10 17 55 211 3.5 2.3 3.2 1700 3966 996 702 1502 0 0 0 0 115 (17.4) 0 0 337 (50.9) 0 29 (4.4) 214 (32.3) 166 (25.1) 195 (29.5) 321 (48.5) 284 (42.9) 551 (83.2) 363 (54.8) 3 (0.5) 603 (91.1) 635 (95.9) 611 (92.3) 406 (61.3) 0 0 1 (0.2) 0 0 5 (0.8) 6 (0.9) 44 (6.6) 44 (6.6) 22 (3.3) 21 (3.2) 35 (5.3) 34 (5.1) 34 (5.1) 34 (5.1) 34 (5.1) 34 (5.1) 34 (5.1) 34 (5.1) 34 (5.1) 34 (5.1) 34 (5.1) 13 (2.0) 12 (1.8) 4 (0.6) 34 (5.1) 34 (5.1) 34 (5.1) 34 (5.1) 34 (5.1) Data below the limit of detection were replaced by half of the reported detection limit values for the geometric mean calculations; bBDL ⫽ below detection limit. Volume 53 June 2003 Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 733 Kim, Hopke, and Edgerton Table 2. Summary of coarse particle mass and 14 species concentrations used for PMF modeling. Concentration (ng/m3) Number of BDLb Species Geometric Mean Arithmetic Mean Min Max Values (%) Number of Missing Values (%) PM10–2.5 NO3⫺ SO42⫺ NH4⫹ Cr Cu Fe Mn Ni V Al Si K Ca Ti 8611 349 285 33 0.73 1.31 4.72 1.20 0.74 0.84 581 1380 139 375 46 10116 457 393 68 0.75 1.2 8.0 1.5 0.75 0.81 767 1816 162 480 54 511 8.6 15 3.5 0.73 1.1 2.3 0.59 0.73 0.79 12 49 7.9 12 2.1 34701 2403 2796 795 1.1 5.6 189 6.9 2.5 2.1 3148 7653 711 3458 240 0 4 (0.6) 24 (3.5) 139 (20.3) 635 (92.7) 606 (88.5) 366 (53.4) 327 (47.7) 636 (92.8) 627 (91.5) 0 0 0 0 3 (0.4) 0 11 (1.6) 11 (1.6) 12 (1.8) 50 (7.3) 52 (7.6) 52 (7.6) 54 (7.9) 47 (6.9) 56 (8.2) 48 (7.0) 56 (8.2) 56 (8.2) 48 (7.0) 56 (8.2) a a Data below the limit of detection were replaced by half of the reported detection limit values for the geometric mean calculations; bBDL ⫽ below detection limit. and F matrix). To decrease rotational freedom, PMF uses nonnegativity constraints on the factors. The parameter FPEAK is used to control the rotations.26 PMF provides a solution that minimizes an object function, Q(E), based on uncertainties for each observation.7,27 This function is defined as 冘冘 n Q共E兲 ⫽ m i⫽1 j⫽1 冤 xij ⫺ 冘 p k⫽1 uij 冥 2 gikfkj (3) where uij is an uncertainty estimate in the jth element measured in the ith sample. The application of PMF depends on the estimated uncertainties for each of the data values. The uncertainty estimation provides a useful tool to decrease the weight of missing and below-detection-limit data in the solution, as well as accounting for the variability in the source profiles. The procedure of Polissar et al.28 was used to assign measured data and the associated uncertainties as the input data to the PMF. The concentration values were used for the measured data, and the summation of the analytical uncertainty and 1/3 of the detection limit value was used as the overall uncertainty assigned to each measured value. Values below the detection limit were replaced by half of the detection limit values, and their overall uncertainties were set at 5/6 of the detection limit values. Missing values were replaced by the geometric mean of the measured values, and their accompanying uncertainties were set at 4 times this geometric mean value. 734 Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association The uncertainty must take into account both the measurement uncertainty and the variability in the source profiles. It also has to help to take into account the differences in scale between major species as compared with the lower-concentration species. In northeastern U.S. aerosol studies,16 PMF separated the S into a high photochemistry source and a low photochemistry source with seasonal differences of the Se/S concentrations. In this study, without adequate Se data, it was found that it was necessary to increase the estimated uncertainties of SO42⫺ and NH4⫹ by a factor of 4 to take the high photochemistry variability into account. Raising the estimated uncertainty of SO42⫺ and NH4⫹ decreases the weight of SO42⫺ and NH4⫹ in the solution. Because of the mass closure problem noted previously, the measured fine particle mass concentrations were included as an independent variable in the PMF modeling to directly obtain the mass apportionment without the usual multilinear regression. The estimated uncertainties of the mass concentrations were set at 4 times their values so that the large uncertainties decreased their weight in the model fit. The results of PMF modeling were then normalized by the apportioned particle mass concentrations so that the quantitative source contributions for each source were obtained. Specifically 冘 冉冊 p x ij ⫽ k⫽1 共ckgik兲 fkj ck (4) Volume 53 June 2003 Kim, Hopke, and Edgerton where ck is directly apportioned mass concentration by PMF for the kth source. To analyze point-source impacts from various wind directions, the CPF29 was calculated using source contribution estimates from PMF, coupled with wind direction values measured on site. To minimize the effect of atmospheric dilution, daily fractional mass contribution from each source relative to the total of all sources was used rather than the absolute source contributions. The same daily fractional contribution was assigned to each hour of a given day to match the hourly wind data. Specifically, the CPF is defined as CPF ⫽ m ⌬ n ⌬ (5) where m⌬ is the number of occurrence from wind sector ⌬ that exceeded the threshold criterion, and n⌬ is the total number of data from the same wind sector. In this study, ⌬ was set at 11.3°. Calm winds (⬍1 m/sec) were excluded from this analysis. The threshold was set at the upper 10th percentile of the fractional contribution from each source. The sources are likely to be located in the directions that have high conditional probability values. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION To determine the number of sources, it is reasonable to experiment with different numbers of sources and find the one with the most physically meaningful results. Also, because rotational ambiguity exists in factor analysis modeling, PMF was run several times with different FPEAK values to determine the range within which the objective function Q(E) value in eq 3 remains relatively constant.26 The optimal solution should lie in this FPEAK range. In this way, subjective bias was avoided to some extent. The final PMF solutions were determined by trial and error with different numbers of sources as well as different FPEAK values and were based on the evaluation of the resulting source profiles. In this study, the robust mode was used to reduce the influence of extreme values on the PMF solution. A data point was classified as an extreme value if the model residual exceeded 4 times the error estimate. The estimated uncertainties of those extreme values were then increased so that the weights of the extreme values in the solution were decreased. The global optima of the PMF solutions were tested using five different seeds of pseudorandom values. Fine Particle Data Eight sources were identified for the fine particles. A value of FPEAK ⫽ 0.2 provided the most physically reasonable source profiles. A comparison of the daily reconstructed fine mass Volume 53 June 2003 contributions from all sources with measured fine mass concentrations is shown in Figure 4. When the uncertainties associated with this data set are considered, the squared correlation coefficient of 0.83 indicates that the resolved sources effectively account for most of the variation in the particle mass concentration. Figure 5 presents the identified source profiles and Figure 6 shows time-series plots of estimated daily contributions to fine particle mass concentrations from each source. Figure 7 shows conditional probabilities of source locations for local point sources. The SO42⫺-rich secondary aerosol has a high concentration of SO42⫺ and shows strong seasonal variation with high concentrations in summer when the photochemical activity is highest. This source includes NH4⫹, which explains 30% of its mass. It also includes OC, which typically becomes associated with the secondary SO42⫺ aerosol. This OC association is consistent with previous Phoenix13 and northeastern U.S.16 aerosol studies. The motor vehicle source is represented by high OC and EC.30 –32 It also includes some soil dust constituents (Si, Fe). This indicates the motor vehicle source is not just vehicle tailpipe source but also street emissions, including resuspended road dust. The ratio of OC/EC is 1.49 for this source, whereas it is more typically 2.05 in fresh gasoline exhaust and 0.72 in diesel emissions for PM10.33 Therefore, this motor vehicle source is a mixture of diesel emissions and particles produced by gasoline-powered vehicles. Watson et al.31,32 reported 0.05– 8.6 wt % of SO42⫺ concentration in motor vehicle exhaust from 1992 and 1995 roadside measurements. In this study, the motor vehicle source has a negligible amount of SO42⫺ that might arise from SO2 emissions where there would not be time for substantial conversion to SO42⫺. Figure 4. Measured vs. predicted fine particle mass concentration. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 735 Kim, Hopke, and Edgerton Figure 5. Source profiles resolved from fine particle samples. coal-fired cement kiln source profiles.34 The high OC concentration of this source indicates that the cement kiln and an OC-rich source are collocated and that their daily emission patterns are similar. Also, a rail yard located approximately 2 km northwest of the site may have mixed with this source. The airborne soil factor contains the characteristic elements Si, Al, Fe, K, and Ti.31,32 It has a few random high peaks. Unpaved roads, construction sites, and windblown soil dust could produce particles of these crustal elements. Those were not separated in this study because their chemical profiles were similar and their daily variations were not enough to separate them. For the seventh source, a metal recycling facility located approximately 0.7 km east of the site is suggested because of the factor characterized by its high mass fraction of Zn, Fe, and Cl.34,35 The Zn/Fe ratio of this source is 1.1. This source has short-term peaks in winter. The facility is used mainly for storage, grinding, shredding, and loading onto railcars. In addition, several metal processing facilities are located approximately 6 km southeast of the site. In Figure 7, there are indications of contributions from the east and southeast. Mixed source II includes high values of EC, Fe, K, Cu, and Pb. The CPF plot (Figure 7) suggests that this factor comes from sources in the southeasterly direction, which include a bus station30,36 located only approximately 200 m southeast of the site. This diesel emission seems to The wood smoke source is characterized by OC, EC, and K.32 This source has a seasonal trend with high values in winter and short-term peaks in spring and summer. The winter peaks indicate residential wood burning, and the spring and summer events are likely to be caused by forest fires. There are also prescribed burnings to the south of Atlanta in winter. The NO3⫺-rich secondary aerosol has a high concentration of NO3⫺. It shows seasonal variation with maxima in winter. These peaks in winter indicate that low temperature and high relative humidity help the formation of NO3⫺ aerosols in Atlanta. This result is consistent with a previous study of aerosol data from three northeastern U.S. sites.16 This source includes NH4⫹, which becomes associated with the secondary NO3⫺ aerosol. The NO3⫺ concentration is 0.98 g/g for this source. In a given source, the summation of species concentrations is often slightly more than 100% because PMF modeling uses a statistical approach and there are uncertainties associated with any of these values. Mixed source I has high OC and Ca concentrations. This factor is likely to include contributions from a cement kiln located approximately 7 km northwest of the monitoring site and an unknown OC-rich source. It is consistent with the conditional probability plot for this source in Figure 6. The cement kiln emission contains OC because this stationary source combusts fossil fuels. However, the ratio of OC/Ca is 2.43 for this source, whereas it is typically 0.54 in Figure 6. Source contributions for fine particle samples. 736 Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association Volume 53 June 2003 Kim, Hopke, and Edgerton Table 3. Average source contributions (g/m3) to fine particle mass concentration. Average Source Contribution (standard error) SO42⫺-rich secondary aerosol Motor vehicle Wood smoke NO3⫺-rich secondary aerosol Mixed source I Airborne soil Metal recycling Mixed source II Total Average Summer Average Winter Average 8.85 (0.21) 3.53 (0.11) 1.72 (0.05) 1.15 (0.03) 0.31 (0.01) 0.18 (0.01) 0.08 (0.003) 0.05 (0.003) 12.1 (0.30) 3.28 (0.12) 1.35 (0.05) 0.80 (0.03) 0.36 (0.02) 0.26 (0.02) 0.06 (0.003) 0.05 (0.003) 6.17 (0.12) 3.74 (0.17) 2.03 (0.08) 1.45 (0.05) 0.27 (0.01) 0.12 (0.006) 0.10 (0.006) 0.06 (0.004) fine particle mass concentration. The SO42⫺-rich secondary aerosol, mixed source I, and airborne soil contributed more to the fine particle mass in summer. The motor vehicle, wood smoke, NO3⫺-rich secondary aerosol, and metal recycling sources contributed more in winter. The slightly winter-high trend of the motor vehicle source is likely caused by the temperature inversions that concentrate pollutants in the surface mixing layer. Mixed source II did not show a strong seasonal trend. Figure 7. Hourly CPF plots for the highest 10% of the mass contibution from fine particle point sources. be mixed with metal processing sources34,35 located in the same direction as the bus station from the monitoring site. The average contributions of each source to the fine particle mass concentration are summarized in Table 3. The seasonal average contributions are also presented (summer: April–September; winter: October–March). The SO42⫺-rich secondary aerosol has the highest source contribution to the fine particle mass concentrations (56%). It is consistent with a study of three northeastern U.S. sites, which identified its contributions of 47, 55, and 51% to the fine particle mass concentration.16 The second contributor is motor vehicles, accounting for 22% of the Volume 53 June 2003 Coarse Particle Data For the coarse particles, the PMF identified five sources with an FPEAK of 0. Table 4 summarizes the five sources and their average mass contributions. As presented in Figure 8, a comparison of the coarse mass contributions from all sources with measured coarse mass concentrations shows good agreement (r2 ⫽ 0.92). Figures 9 and 10 show the identified source profiles and time-series plots of daily contributions to coarse mass concentrations from each source, respectively. Figure 11 shows conditional probability plots for point sources. The airborne soil source is represented by Si, Al, Ca, K, and Ti.31,32 Resuspended road dust is typical in urban areas. There could be transfer of cement-derived Ca to soil, Table 4. Average source contributions (g/m3) to coarse particle mass concentration. Average Source Contribution (standard error) Airborne soil NO3⫺-rich secondary aerosol SO42⫺-rich secondary aerosol Cement kiln Metal recycling Total Average Summer Average Winter Average 5.94 (0.16) 1.61 (0.05) 1.22 (0.05) 1.06 (0.04) 0.13 (0.008) 5.93 (0.21) 1.53 (0.07) 1.39 (0.07) 0.94 (0.05) 0.15 (0.01) 5.95 (0.25) 1.68 (0.08) 1.07 (0.08) 1.16 (0.06) 0.12 (0.01) Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 737 Kim, Hopke, and Edgerton Figure 10. Source contributions for coarse particle samples. Figure 8. Measured vs. predicted coarse particle mass concentration. particularly in dry weather. Nitrate-rich and SO42⫺-rich secondary aerosols are characterized by NO3⫺ and SO42⫺, respectively. The cement kiln source has high Ca levels. As shown in Figure 10, the conditional probability plot of cement kiln points to northwest of the monitoring site, which is consistent with the fine particle plot (see Figure 7). The fifth source has high Si, Al, and Fe levels. This source may be the metal recycling facility. The conditional probability plot of this source shows relatively high contributions from the northwest, northeast, and southeast. The main source of coarse particles is airborne soil (60%), although it is likely that much of the soil is resuspended by the action of motor vehicles. Most urban areas report soil as the major contributor to coarse particles.13 Figure 9. Source profiles resolved from coarse particle samples. 738 Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association The five sources of coarse particles do not have strong seasonal trends, as shown in Table 4. Nitrate-rich and SO42⫺-rich aerosols have seasonal trends that are weak but similar to those of the comparable fine particle sources. Figure 11. Hourly CPF plots for the highest 10% of the mass contribution from coarse particle point sources. Volume 53 June 2003 Kim, Hopke, and Edgerton The cement kiln contributed more in winter. In contrast, the metal recycling source contributed more in summer. CONCLUSIONS Daily integrated PM compositional data measured at a monitoring site in Atlanta were analyzed through PMF. Including particle mass concentrations as independent variables, the PMF effectively resolved eight and five sources for fine particles and coarse particles, respectively. SO42⫺-rich secondary aerosol contributed to the fine particles the most, which is consistent with the results of northeastern U.S. aerosol studies.16 This source impact is higher in summer. Airborne soil contributed to the coarse particles the most. The impacts from the point sources are more clearly seen using PMF results combined with plots of CPFs. Those plots of both fine and coarse particles clearly show the direction of the cement kiln. In addition, this approach revealed the direction of the metal recycling source and the bus station. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study was supported by the Southern Company, Atlanta, GA. REFERENCES 1. Dockery, D.W.; Pope, C.A.; Xu, X.P.; Spengler, J.D.; Ware, J.H.; Fay, M.E.; Ferris, B.G. An Association between Air-pollution and Mortality in 6 United States Cities; New Engl. J. Med. 1993, 329, 1753-1759. 2. Samet, J.M.; Zeger, S.L.; Dominici, F.; Curriero, F.; Coursac, I.; Dockery, D.W.; Schwartz, J.; Zanobetti, A. The National Morbidity, Mortality, and Air Pollution Study. Part II: Morbidity and Mortality from Air Pollution in the United States; Res. Rep. Health Effect Inst. 2000, 94 (Pt 2), 5-79. 3. Pope, C.A.; Burnett, R.T.; Thun, M.J.; Calle, E.E.; Krewski, D.; Ito, K.; Thurston, G.D. Lung Cancer, Cardiopulmonary Mortality, and LongTerm Exposure to Fine Particulate Air Pollution; J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2002, 287 (9), 1132-1141. 4. Clarke, R.W.; Coull, B.A.; Reinisch, U.; Catalano, P.J.; Killingsworth, C.R.; Koutrakis, P.; Kavouras, I.; Lawrence, J.; Lovett, E.G.; Wolfson, J.M.; et al. Inhaled Concentrated Ambient Particles Are Associated with Hematologic and Bronchoalveolar Lavage Changes in Canines; Environ. Health Perspect. 2000, 108 (12), 1179-1187. 5. Laden, F.; Neas, L.M.; Dockery, D.W.; Schwartz, J. Association of Fine Particulate Matter from Different Sources with Daily Mortality in Six U.S. Cities; Environ. Health Perspect. 2000, 108 (10), 941-947. 6. Sarnat, J.A.; Koutrakis, P.; Suh, H. Assessing the Relationship between Personal Particulate and Gaseous Exposures of Senior Citizens Living in Baltimore, MD; J. Air & Waste Manage. Assoc. 2000, 50, 1184-1198. 7. Paatero, P. Least Square Formulation of Robust Nonnegative Factor Analysis; Chemomet. Intell. Lab. Systems 1997, 37, 23-35. 8. Huang, S.; Rahn, K.A.; Arimoto, R. Testing and Optimization Two Factor-Analysis Techniques on Aerosol at Narragansett, Rhode Island; Atmos. Environ. 1999, 33, 2169-2185. 9. Willis, R.D. Workshop on UNMIX and PMF as Applied to PM2.5; EPA 600-A-00 – 048, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Research Triangle Park, NC, 2000. 10. Qin, Y.; Oduyemi, K.; Chan, L.Y. Comparative Testing of PMF and CFA Models; Chemomet. Intell. Lab. Systems 2002, 61, 75-87. 11. Xie, Y.L.; Hopke, P.K.; Paatero, P.; Barrie, L.A.; Li, S.M. Identification of Source Nature and Seasonal Variations of Arctic Aerosol by Positive Matrix Factorization; J. Atmos. Sci. 1999, 56, 249-260. 12. Lee, E.; Chun, C.K.; Paatero, P. Application of Positive Matrix Factorization in Source Apportionment of Particulate Pollutants; Atmos. Environ. 1999, 33, 3201-3212. 13. Ramadan, Z.; Song, X.H.; Hopke, P.K. Identification of Sources of Phoenix Aerosol by Positive Matrix Factorization; J. Air & Waste Manage. Assoc. 2000, 50, 1308-1320. 14. Chueinta, W.; Hopke, P.K.; Paatero, P. Investigation of Sources of Atmospheric Aerosol at Urban and Suburban Residential Area in Thailand by Positive Matrix Factorization; Atmos. Environ. 2000, 34, 3319-3329. 15. Polissar, A.V.; Hopke, P.K.; Poirot, R.L. Atmospheric Aerosol over Vermont: Chemical Composition and Sources; Environ. Sci. Technol. 2001, 35, 4604 – 4621. Volume 53 June 2003 16. Song, X.H.; Polissar, A.V.; Hopke, P.K. Source of Fine Particle Composition in the Northeastern U.S.; Atmos. Environ. 2001, 35, 5277-5286. 17. Peters, T.M.; Vanderpool, R.W.; Wiener, R.W. Design and Calibration of the EPA PM2.5 Well Impactor Ninety-Six (WINS); Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2001, 34, 389-397. 18. Vanderpool, R.W.; Peters, T.M.; Natarajan, S.; Gemmill, D.B.; Weiner, R.W. Evaluation of the Loading Characteristics of the EPA WINS PM2.5 Separator; Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2001, 34, 444-456. 19. Dzubay, T.G.; Stevens, R.K.; Gordon, G.E.; Olmez, I.; Sheffield, A.E.; Courtney, W.J. Composite Receptor Method Applied to Philadelphia Aerosol; Environ. Sci. Technol. 1988, 22 (1), 46-52. 20. Apple, B.R.; Tokiwa, Y.; Kothny, E.L. Sampling of Carbonaceous Particles in the Atmosphere; Atmos. Environ. 1983, 17, 1787-1796. 21. Van Vaeck, L.; Van Cauwenberghe, K.; Janssens, J. The Gas-Particle Distribution of Organic Aerosol Constituents: Measurement of the Volatilization Artifact in Hi-Vol Cascade Impactor Sampling; Atmos. Environ. 1984, 18, 417-430. 22. Miller, M.S.; Friedlander, S.K.; Hidy, G.M.A. Chemical Element Balance for the Pasadena Aerosol; J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1972, 39, 165-176. 23. Hopke, P.K. Receptor Modeling in Environmental Chemistry; Wiley & Sons: New York, 1985. 24. Hopke, P.K. Receptor Modeling for Air Quality Management; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1991. 25. Henry, R.C. Current Factor Analysis Models Are Ill-Posed; Atmos. Environ. 1987, 21, 1815-1820. 26. Paatero, P.; Hopke, P.K.; Song, X.H.; Ramadan, Z. Understanding and Controlling Rotations in Factor Analytic Models; Chemomet. Intell. Lab. Systems 2002, 60, 253-264. 27. Paatero, P. User’s Guide for Positive Matrix Factorization Programs PMF2 and PMF3, Part 1: Tutorial. ftp://rock.helsinki.fi/pub/misc/pmf (accessed Apr 2003). 28. Polissar, A.V.; Hopke, P.K.; Paatero, P.; Malm, W.C.; Sisler, J.F. Atmospheric Aerosol over Alaska 1. Elemental Composition and Sources; J. Geophys. Res. 1998, 103 (D15), 19045-19057. 29. Ashbaugh, L.L.; Malm, W.C.; Sadeh, W.Z. A Residence Time Probability Analysis of Sulfur Concentrations at Ground Canyon National Park; Atmos. Environ. 1985, 19 (8), 1263-1270. 30. Watson, J.G.; Chow, J.C.; Lowenthal, D.H.; Pritchett, L.C.; Frazier, C.A. Differences in the Carbon Composition of Source Profiles for Diesel and Gasoline Powered Vehicles; Atmos. Environ. 1994, 28 (15), 2493-2505. 31. Watson, J.G.; Chow, J.C. Source Characterization of Major Emission Sources in the Imperial and Mexicali Valleys along the US/Mexico Border; Sci. Total Environ. 2001, 276, 33-47. 32. Watson, J.G.; Chow, J.C.; Houck, J.E. PM2.5 Chemical Source Profiles for Vehicle Exhaust, Vegetative Burning, Geological Material, and Coal Burning in Northwestern Colorado during 1995; Chemosphere 2001, 43, 1141-1151. 33. Cadle, S.H.; Mulawa, P.A.; Hunsanger, E.C.; Nelson, K.E.; Ragazzi, R.A.; Barrett, R.; Gallagher, G.L.; Lawson, D.R.; Knapp, K.T.; Snow, R. Composition of Light-Duty Motor Vehicle Exhaust Particulate Matter in the Denver, Colorado Area; Environ. Sci. Technol. 1999, 33, 2328-2339. 34. EPA SPECIATE version 3.2. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Research Triangle Park, NC, 2002. 35. Small, M.; Germani, M.S.; Small, A.M.; Zoller, W.H.; Moyers, J.L. Airborne Plume Study of Emissions from the Processing of Copper Ores in Southeastern Arizona; Environ. Sci. Technol. 1981, 15, 293-299. 36. Lowenthal, D.H.; Zielinska, B.; Chow, J.C.; Watson, J.G. Characterization of Heavy-Duty Diesel Vehicle Emissions; Atmos. Environ. 1994, 28 (4), 731-743. About the Authors Eugene Kim has been a research associate at Clarkson University since December 2001, when he completed a postdoctoral fellowship in the Northwest Particulate Matter and Health Center. He received a Ph.D. in environmental engineering from the University of Washington. Philip K. Hopke is the Bayard D. Clarkson Distinguished Professor at Clarkson University. He has studied airborne PM for 30 years. Eric S. Edgerton is president and chief scientist of Atmospheric Research and Analysis, Inc., in Durham, NC. Address correspondence to: Dr. Philip K. Hopke, Department of Chemical Engineering, Clarkson University, P.O. Box 5705, Potsdam, NY 13699; e-mail: hopkepk@clarkson.edu. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 739