Tasmania`s Energy Sector – an Overview

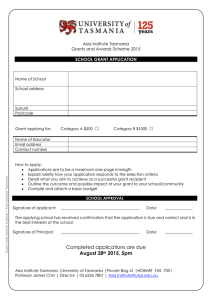

advertisement