May June 2013 Volume 24, Issue 3

advertisement

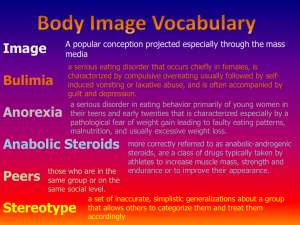

Eating Disorders Review May/June 2013 Volume 24, Issue 3 *********** Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) Defining ARFID By Lindsay Kenney, BA and B. Timothy Walsh, MD Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons Columbia University and New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, New York With the publication of the DSM-5 has come a revised conceptualization of an old eating disorder. Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) has replaced Feeding Disorder of Infancy and Early Childhood, which was described in the DSM-IV. The latter category was very rarely used, and there is almost no information on the characteristics of the children who have it. The new category of ARFID is intended to capture individuals who meet criteria for the existing DSM-IV category, but also to include other individuals with clinically significant eating problems who are not included in the defined DSM-IV categories, and therefore must be assigned a diagnosis of Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (EDNOS). The first critical element in the DSM-5 definition of ARFID is a persistent disturbance in eating that leads to significant clinical consequences, such as weight loss or inadequate growth, a significant nutritional deficiency, dependence on tube feeding or nutritional supplements to sustain adequate intake, and/or impaired psychosocial functioning, such as an inability to eat with others. Significant weight loss and potential nutritional deficiencies should be assessed in a similar way as they are assessed in anorexia nervosa (AN), because physical complications seen in AN ( such as hypothermia, bradycardia, or anemia) may also occur in individuals with potential ARFID. Three additional criteria in DSM-5 are intended to exclude individuals who have a clinically significant problem that is better described in some other way. For example, a diagnosis of ARFID would not be given if the nutritional problems are better explained by a lack of available food or a cultural practice (such as religious fasting), or if the person has substantial and irrational dissatisfaction with body shape or weight (such as in AN or bulimia nervosa (BN), or if the clinical problem is better accounted for by an existing medical condition or another mental disorder. Clinically Significant Restrictive Eating Problems Are Key ARFID was developed to identify individuals presenting with clinically significant restrictive eating problems, including some that meet criteria for the DSM-IV diagnosis of Feeding Disorder of Infancy and Early Childhood. Common eating disturbances seen in a clinical setting that have previously been classified under Feeding Disorder of Infancy and Early Childhood include: impaired development of feeding or eating skills, difficulty with digesting or with intake of fluids or foods, refusal to eat due to a dislike of certain sensory characteristics of foods, and a more general lack of appetite or interest in eating (Bryant-Waugh et al. 2010). All of these presentations will still be classified under ARFID, as will other eating disturbances that previously would have been classified under EDNOS, including: Inadequate intake based on a restricted range of foods eaten or a restricted caloric intake that does not lead to weight loss or significant growth impairment. Individuals with this problem may avoid foods based on certain sensory qualities- such as texture, color, taste, or temperature. An example could be a child who likes only foods that he does not have to chew, and who therefore has great difficulty consuming a range of foods adequate to sustain normal growth and development. Reduced food intake due to an emotional disturbance related to eating, without concern for body shape or weight. These may arise if there are significant problems in the relationship between the child and the caregiver so that meals became fraught with anxiety and unpleasant interactions, so that food intake is repeatedly and seriously interrupted. Reluctance regarding food intake following an eating-related adverse event. A person who significantly restricts food intake due to a reluctance to swallow following a frightening episode of gagging, choking or vomiting may be diagnosed with ARFID. Reasons for the Change in the DSM-5 In the DSM-IV, Feeding Disorder of Infancy or Early Childhood was a diagnosis rarely given and rarely studied. In fact, a recent PubMed search using this diagnostic term identifies no publications within the past 10 years. To meet criteria for the DSM-IV condition, an individual must be under 6 years of age at the time of illness onset, and must persistently fail to eat adequately to gain or maintain a healthy weight for at least 1 month, if no other digestive problem or mental disorder can better account for the observed eating disturbance (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (2000) 4th ed., text rev). In the DSM-IV, a difficult parent-child relationship is emphasized as a potential factor in the development of this feeding disorder. For example, parents who present food or respond to a refusal to eat inappropriately may contribute to an infant developing a general uneasiness around eating. Additionally, the DSM-IV suggests that infants with feeding disorders are more likely to have unpredictable, intrusive, and over-stimulating mothers, who are also more likely to have mental illnesses such as depression or an eating disorder compared to infants without feeding disorders (Chartoor et al., 1998; Lindberg et al., 1996). For this reason, some believe feeding disorders in infancy should be “relational,” and the focus should be on the influence of such parental and environmental factors (Bryant-Waugh et al. 2010), as outlined in the definition from the DSM-IV. Since little is known about the clinical utility of Feeding Disorder of Infancy or Early Childhood and it is not a common diagnosis, the criteria were re-evaluated for the DSM-5. Limitations of the Former Criteria The diagnostic criteria of a Feeding Disorder in Infancy or Early Childhood have apparent limitations, which are addressed and modified in the DSM-5’s definition of ARFID. One limitation of the older diagnosis was its emphasis on weight loss or a failure to gain weight as a necessary clinical determinant of this illness. It is possible that a child may have a disturbance in eating and is avoiding food, yet still manages to gain or maintain a healthy weight (possibly due to a reliance on nutritional supplements), thus excluding him or her from getting a feeding disorder diagnosis (Bryant-Waugh et al. 2010). Individuals with an eating disturbance that interferes with psychosocial functioning may have a clinically significant condition and would, of course, benefit from identification and appropriate treatment, yet the focus on weight loss in the DSM-IV definition may have interfered with such a patient receiving clinical attention. Another limitation to the DSM-IV definition of feeding disorders in infancy is the criterion that onset must occur before age 6, most commonly during the first few years of life, potentially as a result of negative interactions with the caregiver. However, this is clearly not always the case. Clinicians see older adolescents and even adults with a disturbance in eating that impacts either nutrition or social functioning in a negative way (Kreipe & Palomaki 2012), and it is important to evaluate, diagnose, and possibly treat these individuals. Finally, the definition of feeding disorders in infancy includes in its criteria that the disturbance cannot be “due to” some other general medical condition. However, distinguishing a medical condition from a feeding disorder can be difficult, as it is common for an individual with a feeding disorder to have a coexisting medical issue. The revised diagnosis in DSM-5 has been expanded to include clinically significant food avoidance or restriction, with or without an associated medical condition. If the feeding disturbance itself leads to clinically significant changes in nutrition, weight, or social functioning in an individual, a diagnosis of ARFID should be given. Development, Course, and Clinical Expression of ARFID While few data on ARFID have been published, it appears that it usually presents in infancy or childhood, but it can also present or persist into adulthood. For example, aversion to food after a negative event such as choking can occur at any age, while avoidance based on sensory characteristics of food usually starts in early childhood. When presenting in infancy, associated features may include irritability, sleepiness, and distress, and parents may have a difficult time engaging their child in feeding (Zero to Three, 2005). In older children or adolescents, the eating disturbance may be related to emotional difficulties. In the past, similar presentations of eating disturbances related to emotional difficulties (such as low mood or generalized anxiety) were termed “food avoidance emotional disorder,” or FAED (Higgs, Goodyer & Birch, 1989; BryantWaugh, 2010). The course of illness for individuals who develop ARFID is, at the moment, relatively unknown. Avoidance due to sensory characteristics of food may be enduring and last into adulthood (Mascola, Bryson & Agras, 2010). While it is conceivable that individuals with ARFID may go on to develop another eating disorder such as Anorexia Nervosa, no prospective studies are yet available. In children and adults, ARFID may be associated with impaired social functioning and affect family functioning, especially if there is great stress surrounding mealtimes. Distinguishing ARFID from Other Disorders The presence of other psychological disorders may be risk factors for ARFID, such as anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorders, attention deficit disorders, and autism spectrum disorders (Timimi, Douglas & Tsiftsopolou, 1997). If an individual presents with one of these illnesses and an eating problem, a diagnosis of ARFID should be given only when the feeding disturbance itself is causing significant clinical impairment that requires intervention beyond that usually required for the other condition. Similarly, individuals with a history of gastrointestinal conditions such as gastroesophageal reflux may develop feeding disturbances, but a diagnosis of ARFID should be assigned only when the feeding disturbances require significant treatment beyond that needed for the gastrointestinal problems. Treating ARFID Little is currently known about effective treatment interventions for individuals presenting with ARFID. However, given the prominent avoidance behaviors, it seems likely that behavioral interventions, such as forms of exposure therapy, will play an important role. For someone with an emotional disturbance such as depression or anxiety that affects feeding (such as in FAED), cognitive behavioral therapy and other treatments for the underlying condition may be an effective approach for treatment of the eating disorder. Conclusions Idiosyncratic patterns of food intake commonly develop during childhood, but have no clinical significance and remit without intervention. For example, children commonly refuse to eat Brussels sprouts, and this does not constitute an eating disorder! However, the creation of a more inclusive diagnostic category for ARFID should be beneficial in permitting a more specific diagnostic label to be given to clinically significant symptoms that could otherwise go un-identified or untreated. Additionally, since a systematic literature does not yet exist, the definition of ARFID in DSM-5 will hopefully facilitate research to determine the incidence, prevalence, and outcomes of this eating disturbance. References American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Text Revision. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, 2000. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Bryant-Waugh RL, Markham L, Kreipe RE, Walsh BT. Feeding and eating Disorders in Childhood. Int J Eat Disord. 2010; 43:98-111. Chatoor I, Loeffler C, McGee M, Menvielle E, eds. Observational Scale for Mother-Infant Interaction During Feeding. Manual, 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Children’s National Medical Center, 1998. Higgs JF, Goodyer IM, Birch J. Anorexia nervosa and food avoidance emotional disorder. Arch Dis Child. 1989; 64: 346-351. Kreipe RE, Palomaki A. Beyond picky eating: avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. Curr Psychiatry. 1989; 14:421-31. Lindberg L, Bohlin G, Hagekull B, Palmerus K. Interactions between mothers and infants showing food refusal. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1996; 17: 4–347. Mascola AJ, Bryson SW, Agras WS. Picky eating during childhood: a longitudinal study to age 11 years. Eat Behav. 2010; 11:253-257. Timimi S, Douglas J, Tsiftsopoulou K. Selective eaters: a retrospective case note study. Child Care Health Development. 1997; 23:265-278. Zero to Three: Diagnostic classification of mental health and developmental disorders of infancy and early childhood. (revised ed) (DC:0-3R). Washington, DC: ZERO TO THREE Press, 2005. UPDATE: Advocacy Goes to the Schools In March, Virginia Governor Bob McDonnell signed a bill that will direct Virginia schools to provide parental education and screening for eating disorders. This landmark legislation will require that schools send information about eating disorders home to parents annually for all students in grades 5-12 in Virginia. The US Department of Education and the US Department of Health will also develop a “tool kit” to help participating schools perform eating disorders screening. The idea for in-school screening for eating disorders is the brainchild of the National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA), which reasoned that since most schools already do regular health screening, adding an additional screen for eating disorders would involve little additional effort at little additional expense. A second statewide program may follow in New York State, according to Lara Gregorio, manager of NEDA’s STAR Program. Eating disorder school screening legislation was introduced in New York State last year, where it passed the Senate Health Committee and has gained a majority of support in the New York Assembly. Stimulating the Brain to Increase Weight Gain-and Loss Two studies offer intriguing possibilities in chronic illnesss. Two recent studies are showing how stimulating the brain may help patients with anorexia nervosa (AN) gain weight and, in an animal study, halt binge-eating and obesity. A Brain ‘pacemaker’ for patients with AN Deep brain stimulation (DBS) with a neurosurgical implant has produced positive results in a small group of patients with treatment-refractory anorexia nervosa (AN) (Lancet, March 7, 2013 [e-pub before publication]). DBS has been used successfully for patients with neurologic disorders such as chronic pain and Parkinson’s disease, and this is one of the few times the technology has been applied to patients with severe AN. Drs. Nir Lipsman, Andres M. Lozano, a neurosurgeon at the Krembil Neuroscience Centre, and Blake Woodside, medical director of Canada’s largest eating disorders program at Toronto General Hospitals and the University of Toronto, collaborated on the phase I clinical trial. The 6 patients enrolled in their study had a mean age of 38 years and a mean duration of AN for 18 years. In addition to AN, all the patients had comorbidities such as major depressive disorder and obsessive-compulsive disease. The 6 patients also had long histories of hospitalizations for their illnesses (50 hospitalizations among the group), and all were at high risk due to the severity of their disorder and comorbidities. Electrodes were implanted into the subcallosal cingulate gyrus, next to the corpus callosum, a thick bundle of nerve fibers that divides the left and right hemispheres of the brain. The corpus callosum transfers motor, sensory, and cognitive information between the brain hemispheres, and has been linked to human emotions. Once implanted, the electrodes were connected to an implanted pulse generator, very similar to a heart pacemaker, placed below the right clavicle. After the pulse generator was implanted, patients were tested at 1-, 3-, and 6-month intervals. Nine months after the device was implanted, 3 of the 6 patients had gained weight, defined as reaching their highest-ever body mass index (BMI, or kg/m2). For these 3 patients, this was the longest period of sustained weight gain since their illness began. Four of the 6 patients experienced simultaneous changes in mood and anxiety levels. They also gained better control over their emotional responses; researchers reported lessening of urges to binge eat and purge and other AN-linked symptoms. For the first time in their illness, two patients were able to complete treatment in an inpatient eating disorders program. Only a few adverse effects were reported The devices also were associated with several adverse effects, including a seizure in one patient during programming of the device; this occurred about 2 weeks after surgery. Other related events were a panic attack during the implantation surgery, nausea, air embolus, and pain. Drs. Woodside and Lozano and colleagues are planning a second trial that will determine the long-term effects of DBS in a larger number of AN patients. Binge-eating in obese mice is halted by DBS DBS to a precise region of the brain has reduced caloric intake and increased weight loss in obese mice, according to Dr. Casey Halpern and researchers at the University of Pennsylvania (J Neurosci. 2013; 118:487). DBS is currently used to reduce tremors in patients with Parkinson’s disease and is being investigated as a therapy for major depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder. The NIH-funded study reinforced the theory that dopamine deficits are involved in increasing activities that result in obesity, such as binge-eating. Noting that nearly half of obese persons binge-eat, the researchers targeted the nucleus accumbens, a small structure in the brain that is associated with pleasure, motivation, and addiction. Its activity is dependent on two neurotransmitters, dopamine and serotonin. Mice that received DBS ate significantly less of a high-fat food compared to mice that did not have DBS. Dr. Halpern and colleagues also tested the long-term effects of DBS on obese mice that had been given unlimited access to high-fat food. During 4 days of continuous stimulations, the obese mice ate fewer calories and their body weight dropped. These mice also showed improved glucose sensitivity. Future clinical trials will clarify whether DBS can help curb binge eating in humans as well. Using a Stimulant for a Patient with Bulimia Nervosa In a complex case, a stimulant helped quell binge eating and purging. Two clinicians have recently reported what they believe to the first case of successful treatment of a patient with bulimia nervosa (BN), bipolar disorder, and substance dependence with a stimulant, methylphenidate (Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013; 10:30). According to Anna Guerdjikova, PhD, from the Lindner Center of HOPE, and Susan L. McElroy, MD, from the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, the patient was a 32-year-old single woman who was initially hospitalized for treatment of alcohol and cocaine dependence and bipolar disorder. Further examination revealed that she also had BN, purging type. As a child she had been diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which was treated intermittently with methylphenidate. Symptoms of a mood disorder began when she was 8 years old, and manic episodes and numerous bouts with depression followed over time. The patient reported binge-eating episodes followed by self-induced vomiting up to 3 times a day beginning at age 18; these episodes continued until she was 27, when she entered a residential eating disorders treatment program, and her symptoms remitted for 9 months. However, by age 29, she was slipping back into her earlier binge-purge routines. Six months before the authors first saw her, she was binge eating and vomiting daily and had begun abusing laxatives as well. In the 3 months before her latest admission, she reported binge eating and purging at least 50% of the time and abusing alcohol and cocaine 50% of the time. While she was hospitalized, quietiapine (600 mg/day) was given to control her hypomanic and anxiety symptoms, and her substance abuse and BN symptoms at first responded to intensive psychotherapy. She then entered an outpatient care program at the same center and received psychotherapy and medication; her body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) was 19.79 (down from 20.5 at admission). While her depression and mood stabilized and she remained euthymic and alcoholand drug-free for the next 24 months, her BN relapsed, and she again began binge eating and purging daily, until she reached 2 to 3 episodes a day when stressed. Psychotherapy and use of a number of other agents did not help and she reported having problems with concentration and inability to focus on a single task. A stimulant led to full remission of BN symptoms The patient was started on oral doses of methylphenidate to target her BN and ADHD. The starting dosage was 18 mg/day; 1 month later this was increased to 36 mg/day, then to 54 mg/day, and then increased to 72 mg/day. Within a month, she achieved full remission of her BN and was able to control her food intake without binge-eating-she began to choose healthy foods and her eating pattern became regular. Seven months later, her dosage of methylphenidate was switched to 20 mg/day administered through a transdermal patch; within a month this dosage was increased to 30 mg/day, again administered via transdermal patch. Her BMI and vital signs also stabilized, and her concentration and focus improved. Her BN remained in complete remission and she was euthymic and had complete remission of BN for more than a year. In addition, she had gained 3.6 kg since her discharge from the hospital. Two years after discharge from the hospital, she had maintained a stable BMI of 21.0 for at least 8 months. A possible link to serotonin metabolism? Drs. Guerdjikova and McElroy note that methylphenidate acts as a norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor, thus increasing the level of dopamine in the brain. It might also affect serotonin metabolism. While the neurobiology of BN is not completely understood, dysregulation of both dopamine and serotonin neurotransmitter systems has been implicated in the pathogenesis of BN. The authors hypothesize that by exerting its dopamine-modulating properties, methylphenidate might have improved the patient's BN symptoms. They particularly avoided prescribing an amphetamine, to avoid dependence with methylphenidate. While this was only a single case, the authors think further research exploring various therapeutic options for such patients, using randomized, placebo-controlled studies of stimulants in patients with BN, are warranted. (Note: Because such patients are at increased risk of stimulant abuse, clinicians who choose to try out this approach should initially write prescriptions for only small numbers of pills, and then follow these patients very closely. It's a good idea to examine state drug monitoring websites to make sure the patient isn't receiving stimulant drug prescriptions from multiple providers.) Body Mass Index and Subjective Well-Being in Men and Women A susceptibility to eating disorders emerged among women. FinnTwin16, a nationwide longitudinal study of health behaviors in twins and their families, has provided valuable information about overall health and eating disorders as well. Nearly all live twin births during 1975 to 1979 were identified in a central population registry of Finland. When these twins were 16, 17, and 18, and 22 to 28 years of age, they filled out self-report questionnaires on a range of topics. One topic involved body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) and subjective well-being. Dr. Milla S. Linna and colleagues at the University of Helsinki and Helsinki University Hospital noted that while a higher BMI is believed to be related to poorer well-being, there has been little information about the effects of lower BMIs among young adults or how an eating disorder might affect their well-being. To explore these questions, Dr. Linna and researchers used data from the fourth wave of FinnTwin16 questionnaires sent to the study twins. The authors included data from 2415 males and 2825 females 22 to 28 years of age (BMC Public Health. 2013; 13:2431). The authors’ questionnaire assessed a variety of health behaviors and included scales on subjective well-being, as well as a built-in screen for eating disorders developed earlier by one of the authors (Int J Eat Disord. 2006; 39:754). BMIs were calculated based on self-reported heights and weights. For descriptive purposes the authors classified persons with BMIs <18.5 kg/m2 as underweight and those with BMIs >30 kg/m2 as obese. In addition, they applied gender-specific Z-scoring of BMI in all analyses. Women had lower scores on well-being BMIs. Men had a mean BMI of 23.9 kg/m2 and women a mean BMI of 22.2 kg/m2. About 1% of men were underweight, while 7% of women were underweight, or had BMIs less than 18.5 kg/m2. Obesity was relatively rare (4%) among these young adults. In contrast, dieting was common: 42% of women and 24.4% of men reported intentionally losing more than 11 lb at least once. BMI varied considerably when evaluated by eating disorder: the mean BMI for women with a past history of anorexia nervosa (AN) was 21.2 (32 women); 23.6 in women with bulimia nervosa (BN; 37 women); 20.1 with 9 women with a past history of AN and BN (9 women), and 26.2 in the 11 women with binge eating disorder (BED). Subjective well-being. Overall, women reported lower levels of well-being than did men. Lean men tended to have lower levels of subjective well-being than did obese men, but this could not be attributed to a diagnosed eating disorder, since only 5 men had lifetime histories of AN and 2 had lifetime histories of binge eating disorder (BED). Women with a lifetime history of an eating disorder and their healthy twin sisters as well reported lower levels of subjective well-being. Subjective well-being also tended to be lower among women with eating disorders, and women with lifetime diagnoses of both AN and BN had extremely high levels of distress. Differences among men and women Among men, there was an inverse, U-shaped relationship between BMI and subjective well-being. This was constant across all other indicators of psychological health; the highest levels of subjective well-being were found among overweight men. In the current study, estimates of the optimal BMI in terms of subjective well-being in men varied from 26.1 to 28.9 kg/m2. The authors surmised that being in the “overweight” category might be beneficial for young men’s psychological health, partly because men usually have a higher proportion of lean muscle mass compared to women. BMI does not differentiate between fat and muscle tissue, so having a BMI in the overweight range did not necessarily imply an excess fat tissue. Overall, women reported lower levels of subjective well-being than men, and women with lifetime DSM-IV eating disorders had a U-shaped relationship between BMI and life satisfaction. Interestingly, a similar effect was noted in the twin sisters of women with a lifetime eating disorder who did not report any psychopathology related to eating or weight. In fact, the optimal BMI for subjective well-being appeared to be in the overweight range: 26.4 to 29.0 kg/m2; this was true even after excluding women with BED from the analysis. The authors suggest that the relationship between BMI and subjective well-being can be attributed to a susceptibility to eating disorders in women. This might imply that body weight might play a greater role in the relationship between subjective well-being among these women compared to women without a susceptibility to eating disorders. Another explanation would be that when being exposed to mental distress, women who are more susceptible to developing an eating disorder more readily react by either losing or gaining weight. Colorectal Cancer and Weight Loss Surgery A possibility that dietary changes may play some role. Does surgery for obesity increase the risk of developing colon cancer? Yes, say Swedish and British researchers. When the researchers evaluated data from more than 77,000 obese patients, they found the risk of developing colorectal cancer was twice as high among those who had gastric weight loss surgery as among the general population (Ann Surg. 2013; March 6 [Epub ahead of print]). However, the researchers said results should not discourage severely obese patients from having gastric surgery. The risk of colorectal cancer was 26% higher among obese patients who did not have surgery than in the general population. Dr. Jesper Lagergren, of Kings College, London, and the British and Swedish researchers conducted their nationwide retrospective register-based cohort study in Sweden. Patients were divided into an obesity surgery cohort (15,095 patients) and an obesity but no surgery cohort (62,016) patients). The risk for developing colorectal cancer rose with the length of time after surgery. When the researchers looked only at patients who had surgery more than 10 years before the end of the study period, the risk was 200 times that of obese persons in the general population. Thus, the authors concluded that obesity surgery seems to be linked to an increased risk of colorectal cancer over time. They suggest that surveillance with colonoscopy should be part of the long-time follow-up for the growing population of patients who undergo obesity surgery. While there is no clear answer to why obesity surgery might lead to the elevated risk of developing colon cancer; one possibility is that dietary changes after surgery, particularly increasing the protein content of the diet, could raise the risk, according to Dr. Lagergren. A Web-based Treatment Program Offers Intensive Therapeutic Contact Dutch adults with eating disorders go online, with follow-up. Twenty years after the Internet first became available to the general public, Internet-based treatment programs for patients with eating disorders are proliferating and producing positive results. One pilot program in the Netherlands adds intensive therapeutic contact for participants. Elke D ter Huurne and Cor A. J. DeJong, MD, PhD, and colleagues recently tested a web-based treatment program that provided intensive personalized communication between eating disorder patients and individual therapists (J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e12). The Dutch researchers developed the program because few Dutch eating disorder patients are treated by mental health care professionals. The study used a pre- and post design with 6-week and 6-month follow-ups to measure eating disorder psychopathology, body dissatisfaction, body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), physical and mental health, and quality of life. Participants included 165 adult patients with eating disorders: 115 with eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS), 24 patients with purging-type bulimia nervosa (BN), and 24 patients with non-purging type BN. The web site was written for general audiences and all eating disorder diagnostic groups, to reach a broad crosssection of the public. A two-part program using multiple techniques The final study group included 165 adults who visited the website and signed up for the web-based treatment program between January and December 31, 2010. The structured, two-part treatment program used cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and motivation interviewing, as well as psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, self-control techniques and exposure techniques. The goals of the online program were to improve eating disorder psychopathology and to reduce body dissatisfaction. The treatment program lasted about 15 weeks, and patients visited the web site once or twice a week, keeping regular contact with their therapist. The therapist always responded within 3 working days, and monitored the progress of the treatment program. Participants could log in at any time they wished and had a personal space and dossier, so they could have access to messages sent by the therapist. Patients also had the option to request a face to face meeting or direct telephone contact with the therapist. The first part of the web-based treatment program included 4 assignments and at least 7 contacts with a therapist, with a focus on an analysis of the patient's eating behavior. Patients registered their daily eating behaviors, analyzed their eating situations, and described the advantages and disadvantages of their eating problems. At the end of part 1, patients received personal advice from the therapist, who had a bachelor's degree in nursing or social work or a Masters degree in psychology. All therapists had also successfully completed an intensive training program before the intervention began. The therapists also had access to expert advice from a multidisciplinary treatment team, including psychologists, a dietitian, and supervisors. Part 2 of the online program began with setting goals for eating behavior, exercising patterns, self-weighing, and compensatory behaviors. Participants had 6 assignments and at least 14 contacts geared to helping the patient reach goals and make desired behavioral changes. At baseline and at the 6-week and 6-month follow-ups, participants completed a series of online self-report questionnaires and reported their satisfaction with the program. Most found the program to be effective Slightly more than half of the original participants (86, or 52%) completed the online program. Most reported that they found the web-based treatment to be an effective method for treating their eating disorders and nearly all stated that they would recommend the program to others. A key factor tied to patient satisfaction was the support of the therapist, according to the participants. The web-based treatment program successfully changed the eating disorder psychopathology in patients with eating disorders, and the improvement was sustained at 6-week and 6-month follow-up. The authors did not find any significant improvement in BMI for participants who were underweight (defined as a BMI <18.5 kg/m2) or overweight (BMI= 25-30 kg/m2). The authors did point out that one weakness of their program was the 46% attrition rate. Those who completed the program and those who did not differed significantly on several baseline characteristics. Baseline physical and mental health as well as participants' degree of body satisfaction were markers of who would successfully use and complete the web-based treatment program. Thus, the authors view the web-based treatment program as an important and accessible first step in stepped-care treatment. The authors are continuing their study with a randomized controlled trial to provide more concrete evidence of the effects of the online intervention. BOOK REVIEW: The Oxford Handbook of Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders: Developmental Perspectives (James Lock, editor (Oxford Library of Psychology). Oxford University Press, 2012; 324 pages; $135) Handbooks in the Oxford University Library of Psychology are meant to cover subfields of psychology and to cover focal areas in depth and detail. This series previously published the Oxford Handbook of Eating Disorders, edited by W. Stewart Agras. Now James Lock, Professor of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at Stanford, has edited an excellent companion volume. For this compilation, Dr. Lock, who has contributed significant original research and scholarly writings, most notably in areas of family treatment for adolescent anorexia nervosa, has drawn on the talents of a highly accomplished international group of scientists and clinicians from the US, Canada, Great Britain, Germany, and Austria. The resulting Handbook authoritatively surveys developmental considerations in epidemiology and risk for eating disorders; assessment; interventions; and, finally, includes an excellent examination of contemporary translational issues linking brain circuitry, cognitive reward processing, and eating disorders. In each section and in many of the individual chapters, a wide range of biological, psychological, family, and social contributions are integrated from the developmental perspective, giving the book great coherence. Throughout the book the literature reviews are thorough and the accompanying scholarship is discerning. While many of the chapters are outstanding, several are particularly commendable. A chapter reviewing developmental approaches to the diagnosis and treatment of eating disorders by Julia Heumer and colleagues nicely diagrams temporal and cross-domain relationships seen in the developmental, phenomenological and treatment complexities encountered in eating disorders among children and adolescents. Similarly, Nancy Zucker and Christopher Harshaw's chapter on emotions, attention, relationships, and developmental models of emotional self-regulation is noteworthy. Simon Gowers and Claire Bullock's chapter on choosing treatment settings is worth careful consideration by all caregivers and families, and will be particularly useful to those who might have access to the varied types of resources described. All of the chapters are written at a high level of sophistication, and, among other topics, cover such issues as prevention, media exposure, gender issues, diagnosis, family evolution and family process in relation to eating disorders, physical symptoms and management of physically ill children, specific attention to issues of infancy, middle childhood and later adolescence and young adulthood, binge eating and bulimia nervosa in the context of obesity, and developmental psychopharmacology in relation to eating disorders treatment. This book will serve as a very useful guide and resource for students, advanced scholars, researchers and child-adolescent mental health clinicians who deal with children and adolescents with eating disorders. — J.Y. Over-exercising: A Warning Sign of Suicidality Among Patients with Bulimia Nervosa A useful target for treatment intervention, say the authors of 4 studies. Excessive exercise by women with bulimia nervosa (BN) has been linked to suicidal gestures and attempts, according to the results of four studies by April R. Smith, PhD, and researchers at Miami University, Oxford, OH (Psychiatry Res 2013; 206:246). The first study evaluated whether over-exercising predicted suicidal behavior, after controlling for other eating disorder behaviors. This study included 204 women, 144 of whom had DSM-IV -defined BN. Dr. Smith and her colleagues found that the frequency of over-exercising, defined as “hard exercise used as a means of controlling weight or shape,” significantly predicted suicidal gestures and attempts, even after other bulimic behaviors, such as vomiting, purging, and fasting, were taken into consideration. Over-exercising was the only variable that maintained a significant relationship with suicidal behavior. In the second study, the researchers tested the prospective association between over-exercise and acquired capability for suicide (ACS, defined as fearlessness about lethal self-injury) in a sample of 171 college students who were followed for 3 to 4 weeks. Over-exercise predicted ACS. In the third study, involving 467 college students, pain insensitivity accounted for the relationship between over-exercise and ACS. A fourth study tested whether ACS accounted for the relationship between over-exercise and suicidal behavior in a sample of 512 college students. ACS accounted for the relationship between over-exercise and suicidal behavior. The researchers think that their results may help explain the increased rate of suicidal behavior displayed by persons with BN. It also is an important treatment target for individuals with BN who are currently over-exercising. Q & A: Weird Food Combinations Q. One of my patients who struggles with severe binge eating recently confessed that she loves to create weird food combinations for herself (such as chocolate fudge on oatmeal with bacon chips and pretzel crumbs), but she permits herself to put these dishes together only when she’s alone because she’s too embarrassed to eat this way in front of her family and friends. Is this something I should be asking other patients about? (R.C., Cheshire, CT) A. Creating weird “concoctions” is a reasonably common occurrence, particularly among overweight individuals and among individuals who binge eat. In a recent study of 407 college students plus 45 patients being treated for compulsive overeating or binge-eating disorders, 24.6% reported that they sometimes concocted food mixtures for themselves that they were too ashamed or embarrassed about to make in front of others. The types of mixtures ranged all over the food map, but generally included at least one high-fat ingredient. Common ingredients were cheese, flour, sugar, chocolate, and eggs. They included sweet, mixed sweet and salty, primarily salty, and condiment/savory types of mixes. Some of these concoctions, in fact, might be considered creative and serve as starting points for inventive cuisines or fad dishes, although none seem particularly health-oriented. Often individuals reported feelings of excitement and craving associated with concocting such food mixtures. Not surprisingly, after eating their concoctions 16% felt guilt and 13% reported feeling disgust. Concocting behavior was associated both with measures of binge-eating intensity and severity and with measures of dietary restraint (Int J Eat Disord. 2013; 46:213). Clinicians might want to inquire about concocting and, just as important, learn about and discuss the various anticipatory and consequent motivations and emotions their patients experience in association with these eating episodes. — J.Y. Reprinted from: Eating Disorders Review Gürze Books • P.O. Box 2238 • Carlsbad, CA 92018 phone (800) 756 - 7533 • Fax (760) 434 - 5476 catalogue@gurze.net • www.bulimia.com