2015 Sustainability Assessment Report

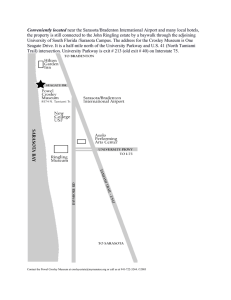

advertisement