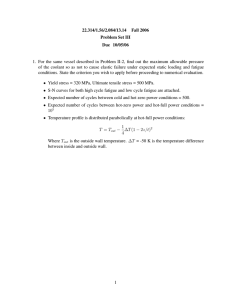

Working Long Hours

advertisement