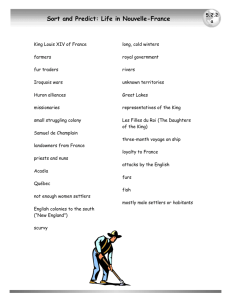

Vivre comme frères: Native-French Alliances in the St Lawrence

advertisement