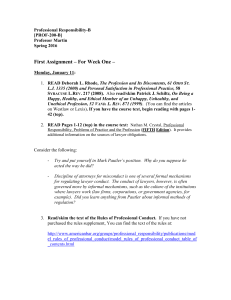

Putting the Legal Profession`s Monopoly on the Practice of Law in a

advertisement